Conserving Missouri's Wild and Managed Pollinators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthidium Manicatum, an Invasive Bee, Excludes a Native Bumble Bee, Bombus Impatiens, from floral Resources

Biol Invasions https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-018-1889-7 (0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,-volV) ORIGINAL PAPER Anthidium manicatum, an invasive bee, excludes a native bumble bee, Bombus impatiens, from floral resources Kelsey K. Graham . Katherine Eaton . Isabel Obrien . Philip T. Starks Received: 15 April 2018 / Accepted: 21 November 2018 Ó Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 Abstract Anthidium manicatum is an invasive pol- response to A. manicatum presence. We found that B. linator reaching widespread distribution in North impatiens avoided foraging near A. manicatum in both America. Male A. manicatum aggressively defend years; but despite this resource exclusion, we found no floral territories, attacking heterospecific pollinators. evidence of fitness consequences for B. impatiens. Female A. manicatum are generalists, visiting many of These results suggest A. manicatum pose as significant the same plants as native pollinators. Because of A. resource competitors, but that B. impatiens are likely manicatum’s rapid range expansion, the territorial able to compensate for this resource loss by finding behavior of males, and the potential for female A. available resources elsewhere. manicatum to be significant resource competitors, invasive A. manicatum have been prioritized as a Keywords Exotic species Á Resource competition Á species of interest for impact assessment. But despite Interspecific competition Á Foraging behavior Á concerns, there have been no empirical studies inves- Pollination tigating the impact of A. manicatum on North Amer- ican pollinators. Therefore, across a two-year study, we monitored foraging behavior and fitness of the common eastern bumble bee (Bombus impatiens) in Introduction With increasing movement of goods and people Electronic supplementary material The online version of around the world, introduction of exotic species is this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-018-1889-7) con- increasing at an unprecedented rate (Ricciardi et al. -

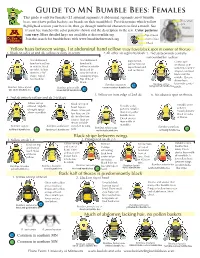

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble Three small bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns ® can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Bee Front of face Squad Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee C patch. two-spotted bumble bee C brown-belted bumble bee C 5. Yellow on front edge of 2nd ab 6. No obvious spot on thorax. 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

Bumble Bee Abundance in New York City Community Gardens: Implications for Urban Agriculture

Matteson and Langellotto: URBAN BUMBLE BEE ABUNDANCE Cities and the Environment 2009 Volume 2, Issue 1 Article 5 Bumble Bee Abundance in New York City Community Gardens: Implications for Urban Agriculture Kevin C. Matteson and Gail A. Langellotto Abstract A variety of crops are grown in New York City community gardens. Although the production of many crops benefits from pollination by bees, little is known about bee abundance in urban community gardens or which crops are specifically dependent on bee pollination. In 2005, we compiled a list of crop plants grown within 19 community gardens in New York City and classified these plants according to their dependence on bee pollination. In addition, using mark-recapture methods, we estimated the abundance of a potentially important pollinator within New York City urban gardens, the common eastern bumble bee (Bombus impatiens). This species is currently recognized as a valuable commercial pollinator of greenhouse crops. However, wild populations of B. impatiens are abundant throughout its range, including in New York City community gardens, where it is the most abundant native bee species present and where it has been observed visiting a variety of crop flowers. We conservatively counted 25 species of crop plants in 19 surveyed gardens. The literature suggests that 92% of these crops are dependent, to some degree, on bee pollination in order to set fruit or seed. Bombus impatiens workers were observed visiting flowers of 78% of these pollination-dependent crops. Estimates of the number of B. impatiens workers visiting individual gardens during the study period ranged from 3 to 15 bees per 100 m2 of total garden area and 6 to 29 bees per 100 m2 of garden floral area. -

Bombus Impatiens, Common Eastern Bumblebee

Bombus impatiens, Common Eastern Bumble Bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Christopher J. Fellows, Forest Huval, T.E. Reagan and Chris Carlton Description The common eastern bumble bee, Bombus impatiens, is an important native pollinator found in the eastern United States and southern Canada. Adult bees are covered with short, even hairs across their bodies. They are mostly black with a yellow thorax (middle section) and an additional yellow stripe at the base of the abdomen. As with other social insects, the different forms, or castes, of B. impatiens vary in size. Worker bumble bees measure from 1/3 to 2/3 of an inch in length (8.5-16 mm), while drones measure ½ to ¾ of an inch (12 to 18 mm). Queen bumble bees are the largest members of the three castes, measuring between 1/3 of an inch to 1 inch (17 and 23 mm) in length. Larvae are rarely seen and are enclosed with the nest brood cells for the duration of their A common eastern bumble bee resting on a flower. Note development. They are pale, legless grubs around 1 inch the yellow patch of hairs on the forward portion of the thorax (David Cappaert, Bugwood.org). (25 mm) in length. At least six additional species of bumble bees have been construction. Within the hollow fiber ball, the queen documented in Louisiana, with another two species possibly deposits a lump of nectar-moistened pollen. The queens present but not confirmed. Identifications are mainly based also construct honey pots near the nest entrance using on the patterns of coloration of the body hairs, but these the secretions of her wax glands. -

Creating Economically and Ecologically Sustainable Pollinator Habitat District 2 Demonstration Research Project Summary Updated for Site Visit in April 2019

Creating Economically and Ecologically Sustainable Pollinator Habitat District 2 Demonstration Research Project Summary Updated for Site Visit in April 2019 The PIs are most appreciative for identification assistance provided by: Arian Farid and Alan R. Franck, Director and former Director, resp., University of South Florida Herbarium, Tampa, FL; Edwin Bridges, Botanical and Ecological Consultant; Floyd Griffith, Botanist; and Eugene Wofford, Director, University of Tennessee Herbarium, Knoxville, TN Investigators Rick Johnstone and Robin Haggie (IVM Partners, 501-C-3 non-profit; http://www.ivmpartners.org/); Larry Porter and John Nettles (ret.), District 2 Wildflower Coordinator; Jeff Norcini, FDOT State Wildflower Specialist Cooperator Rick Owen (Imperiled Butterflies of Florida Work Group – North) Objective Evaluate a cost-effective strategy for creating habitat for pollinators/beneficial insects in the ROW beyond the back-slope. Rationale • Will aid FDOT in developing a strategy to create pollinator habitat per the federal BEE Act and FDOT’s Wildflower Program • Will demonstrate that FDOT can simultaneously • Create sustainable pollinator habitat in an economical and ecological manner • Reduce mowing costs • Part of national effort coordinated by IVM Partners, who has • Established or will establish similar projects on roadside or utility ROWS in Alabama, Arkansas, Maryland, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Idaho, Montana, Virginia, West Virginia, and Tennessee; studies previously conducted in Arizona, Delaware, Michigan, and New Jersey • Developed partnerships with US Fish & Wildlife Service, Army Corps of Engineers, US Geological Survey, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Rutgers University, Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Chesapeake Wildlife Heritage, The Navajo Nation, The Wildlife Habitat Council, The Pollinator Partnership, Progressive Solutions, Bayer Crop Sciences, Universities of Maryland, Ohio, West Virginia, and the EPA. -

Bumble Bees Are Essential

Prepared by the Bombus Task Force of the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign (NAPPC) Photo Sheila Colla Rusty-patched bumble bee, Bombus affi nis Declining North American Bumble Bees Photo David Inouye Western bumble bee, Bombus occidentalis Bumble Bees Helping Photo James Strange are Pollinators Essential Thrive Franklin bumble bee, Bombus franklini Bumble Bee Facts Photo Leif Richardson Globally, there are about 250 described species Some bumble bee are known to rob fl owers of bumble bees. They are found primarily in the of their nectar. Nectar robbing occurs when temperate zones of North and South America, a bee extracts nectar from a fl ower without and Eurasia. coming into contact with its reproductive Yellow-banded bumble bee, Bumble bees are documented to pollinate parts (i.e. anthers and/or stigma), usually Bombus terricola many important food crops. They are also more by biting a hole at the base of the fl ower. Photo Ron Hemberger effective than honey bees at pollinating crops Bumble bees are effective buzz pollinators grown in greenhouses. of several economically important plants in When most insects are inactive due to cold the family Solanaceae such as tomato, bell temperatures bumble bees are able to fl y by pepper and eggplant. In buzz pollination warming their fl ight muscles by shivering, bees extract pollen from a fl ower by American bumble bee, enabling them to raise their body temperature vibrating against the fl ower’s anthers, Bombus pensylvanicus as necessary for fl ight. making an audible buzzing noise. Instead of starting their own colonies, some Currently, the Common Eastern bumble bee bumble bee species have evolved to take over (Bombus impatiens) is the only species being another species’ colony to rear their young. -

PETITION to LIST the Rusty Patched Bumble Bee Bombus Affinis

PETITION TO LIST The rusty patched bumble bee Bombus affinis (Cresson), 1863 AS AN ENDANGERED SPECIES UNDER THE U.S. ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT Female Bombus affinis foraging on Dalea purpurea at Pheasant Branch Conservancy, Wisconsin, 2012, Photo © Christy Stewart Submitted by The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation Prepared by Sarina Jepsen, Elaine Evans, Robbin Thorp, Rich Hatfield, and Scott Hoffman Black January 31, 2013 1 The Honorable Ken Salazar Secretary of the Interior Office of the Secretary Department of the Interior 18th and C Street N.W. Washington D.C., 20240 Dear Mr. Salazar: The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation hereby formally petitions to list the rusty patched bumble bee (Bombus affinis) as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act, 16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq. This petition is filed under 5 U.S.C. 553(e) and 50 CFR 424.14(a), which grants interested parties the right to petition for issue of a rule from the Secretary of the Interior. Bumble bees are iconic pollinators that contribute to our food security and the healthy functioning of our ecosystems. The rusty patched bumble bee was historically common from the Upper Midwest to the eastern seaboard, but in recent years it has been lost from more than three quarters of its historic range and its relative abundance has declined by ninety-five percent. Existing regulations are inadequate to protect this species from disease and other threats. We are aware that this petition sets in motion a specific process placing definite response requirements on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and very specific time constraints upon those responses. -

Mass Flowering Crops As a Conservation Resource for Wild Pollinators (Hymenoptera: Apoidea)

JOURNAL OF THE KANSAS ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY 89(2), 2016, pp. 158–167 Mass Flowering Crops as a Conservation Resource for Wild Pollinators (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) 1*, 2 1 2 KATHERINE J. TODD, MARY M. GARDINER, AND ERIK D. LINDQUIST ABSTRACT: Habitat management within agroecosystems can conserve wild pollinator communities by providing nesting and floral resources. However, demarcating arable land for conservation may reduce farm income. A conciliatory habitat management plan thus consists of planting harvestable commodities which offer pollinator resources. This study’s goal was to determine whether a single species annual flowering crop could support an abundant and diverse wild pollinator community despite its own uniformity. Local bee communities were sampled using pan traps and hand collection within sixty 10 m2 plots of a sunflower, Helianthus annuus L., field and thirty 10 m2 plots within a meadow three times throughout August, 2012. In total, 2316 bees were collected with Bombus impatiens Cresson constituting 81.5% of sampled bees. Examined collectively, hand collections yielded significantly higher bee abundances in the sunflower field (P , 0.01) across every sampling date. Conversely, an equivalent number of pan-trapped bees occurred among habitats for all sampling dates except week three (P 5 0.02) when a greater abundance was observed in the sunflower habitat. Species diversity did not differ (Phand 5 0.99, Ppan 5 0.97) between habitats although community composition differed with high significance (P , 0.01) indicating that these habitats had comparable diversity levels but attracted particular bee assemblages. Our study identifies sunflower crops as useful pollinator resources, especially for Bombus species, and provides insight into single species annual crops’ potential contribution to pollinator conservation. -

Bumble Bees of Virginia

Many bumble bees WHAT CAN YOU DO? VIRGINIA WORKING LANDSCAPES are in decline. Plant native plants! Bumble bees need a stable source of nectar and pollen throughout the growing season, so plant a B u m b l e B e e s suite of native flowers that bloom from early spring to fall. Native plants are recommended because they are beneficial to other insects and wildlife as well. For tips on gardening with native plants, visit the of Virginia Virginia Native Plant Society’s website at: www.vnps.org Bombus impatiens colony, T’ai Roulston Reduce or stop using pesticides! If you use pesticides, visit www.xerces.org to learn Bumble bees are invaluable pollinators. We which chemicals are the most toxic to bees and rely on them to pollinate our fruits, vegetables, how and when to apply pesticides in order to and thousands of native plant species. minimize impacts to bees. Many of our North American bumble bees are Protect the nest! experiencing steep population declines. For Bumble bees nest in the ground during the summer example, the once common Bombus affinis, the and queens overwinter just an inch or two below the rusty-patched bumble bee, has declined by soil’s surface. If you see an area of your yard with a lot of bee activity, do not disturb it if possible. Post- roughly 80% and is only found in isolated areas pone tilling and other soil disturbance practices in within its historic range. Threats to bumble this area in the early spring to allow queens to bees include parasites, disease, habitat loss, emerge. -

Conservation Management Guidelines for the Rusty Patched Bumble Bee (Bombus Affinis) Version 1.6 February 27, 2018

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of the Interior Conservation Management Guidelines for the Rusty Patched Bumble Bee (Bombus affinis) Version 1.6 February 27, 2018 Photograph by Tamara Smith, UWFWS Table of Contents Background 1 Species Needs and Targets 1 Needs 1 Management Objectives and Targets for High Quality Rusty Patched Bumble Bee Habitat 4 1. Objective One – Create, enhance, or maintain foraging habitat 4 2. Objective Two – Create, enhance, or maintain nesting habitat 5 3. Objective Three – Create, enhance, or maintain overwintering habitat 5 4. Objective Four – Create, enhance, or maintain target habitat features 5 Actions that Could Cause Take 6 Conservation Management Recommendations 6 Protect, Create, Restore, and Maintain Habitats 6 Prescribed Fire 7 Mowing/Haying 9 Grazing 10 Pesticide Use 11 Insecticide Use 11 Herbicide Use 12 Commercial Bumble Bees 13 Commercial Honey Bees 13 Coordinated Management among Nearby Sites 14 Literature Cited 15 Background On January 11, 2017, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) published the final rule to list the rusty patched bumble bee (Bombus affinis) as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2017). The listing became effective on March 21, 2017. For more information about the species, as well as guidance under the Endangered Species Act, visit our website www.fws.gov/midwest/endangered/insects/rpbb. The purpose of this document is to provide voluntary management guidance to help FWS, other federal agencies, state agencies, private landowners and land managers manage their land to benefit the rusty patched bumble bee. -

Understanding Habitat Effects on Pollinator Guild Composition in New York State and the Importance of Community Science Involvem

SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Digital Commons @ ESF Dissertations and Theses Fall 11-18-2019 Understanding Habitat Effects on Pollinator Guild Composition in New York State and the Importance of Community Science Involvement in Understanding Species Distributions Abigail Jago [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/etds Part of the Environmental Monitoring Commons, and the Forest Biology Commons Recommended Citation Jago, Abigail, "Understanding Habitat Effects on Pollinator Guild Composition in New York State and the Importance of Community Science Involvement in Understanding Species Distributions" (2019). Dissertations and Theses. 117. https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/etds/117 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ ESF. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ESF. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. UNDERSTANDING HABITAT EFFECTS ON POLLINATOR GUILD COMPOSITION IN NEW YORK STATE AND THE IMPORTANCE OF COMMUNITY SCIENCE INVOLVEMENT IN UNDERSTANDING SPECIES DISTRIBUTIONS By Abigail Joy Jago A thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry Syracuse, New York November 2019 Department of Environmental and Forest Biology Approved by: Melissa Fierke, Major Professor/ Department Chair Mark Teece, Chair, Examining Committee S. Scott Shannon, Dean, The Graduate School In loving memory of my Dad Acknowledgements I have many people to thank for their help throughout graduate school. First, I would like to thank my major professor, Dr. -

The Pollinator Pantry Ambassadors of the White-Lined Sphinx Moth (Hyles Lineata) St

The Hummingbird Clearwing Moth (Hemaris thysbe) Pollinator Notes: The Pollinator Pantry Ambassadors of The White-lined Sphinx Moth (Hyles lineata) St. Louis County The Snowberry Clearwing Moth (Hemaris diffinis) Nine-Spotted Ladybug Beetle ( Coccinella novmnotata) 314-615-4FUN www.stlouisco.com/ Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus) Just who are the "primary pollinators" in the St. Louis Country's pan- try? Let's meet them and their "ambassadors"! These mentioned representatives, our pollinator "ambassadors" were chosen "bee"-cause they are the most familiar, most efficient, most common, least aggressive, sometimes truly unique or just the easiest to recognize "pollen transporters". These pollinators are also the easiest to attract. They are fun to watch visiting our flowers and need a place to call "home" in our Hoverfly landscape. These all can "bee" a welcomed part of our neighbor- ( Toxomerus sp. Diptera) hoods! These are our St. Louis County Pollinator Pantry Ambassadors. The Butterfly and Skipper Ambassadors: The Mason and Leaf Cutter Bee Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) Ambassador: Silver-spotted Skipper ( Epargyreus clarus) Orchard (Osmia lignaria) The gentle orchard bee represents the mason The Nectar Moth Ambassadors: bees and leaf cutter bees (Osmia spp. and Megachile spp.) Silver-spotted Skipper The Snowberry Clearwing Moth Orchard Bee (Osmia lignaria) ( Epargyreus clarus) (Hemaris diffinis) The Honey Bee Ambassador: The Hummingbird Clearwing Moth Western Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) (Hemaris thysbe) The ambassador for honey bees is the busiest of The White-lined Sphinx bees, the western or European honey bee. It is the most (Hyles lineata) common of the species of honey bees. The real value of the honey bees is not the pro- The Hummingbird Ambassador: duction of honey.