Food System Analysis of Arua District in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vote:127 Muni University

Education Vote Budget Framework Paper FY 2020/21 Vote:127 Muni University V1: Vote Overview (i) Snapshot of Medium Term Budget Allocations Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures Billion Uganda Shillings FY2018/19 FY2019/20 FY2020/21 MTEF Budget Projections Approved Spent by Proposed 2021/22 2022/23 2023/24 2024/25 Outturn Budget End Sep Budget Recurrent Wage 6.828 9.207 1.647 9.207 9.207 9.207 9.207 9.207 Non Wage 4.401 3.883 0.905 3.883 4.659 5.591 6.710 8.052 Devt. GoU 4.508 4.200 0.031 4.200 4.200 4.200 4.200 4.200 Ext. Fin. 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 GoU Total 15.737 17.290 2.583 17.290 18.067 18.999 20.117 21.459 Total GoU+Ext Fin 15.737 17.290 2.583 17.290 18.067 18.999 20.117 21.459 (MTEF) A.I.A Total 0.476 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 Grand Total 16.213 17.290 2.583 17.290 18.067 18.999 20.117 21.459 (ii) Vote Strategic Objective 1. To produce graduates with positive attitude, hands-on skills and experience, resilience, and favorable global competitiveness. 2. To promote Quality research, innovation and roll out finding for societal transformation. 3. To develop knowledge and information preservation and dissemination Centre at the University. 4. To engage Community with dynamic knowledge, skills, and technology transfer and service partnerships 5. -

Muni University P

MUNI UNIVERSITY P. O. Box 725, Arua Tel: +256-476-420311/2/3 • Board (HESFB). students who have qualified total of 8 Success- for higher education in rec- HESFB’s Peterson Mu- ful loan scheme ognised Higher Education A hanguzi, the Loans Officer in beneficiaries who will be Institutions but are unable to charge of Northern Uganda • studying at Muni University support themselves. and Bob Muwagira, the Sen- beginning 2021/2022 aca- ior Communication Officer The loans are intended to demic year have signed con- were at Muni University on increase equitable access to tracts with the Higher Edu- 28th January 2021, and sen- Technical and Higher educa- cation Students Financing sitised the loan beneficiaries tion and support highly qual- on how they will access and ified Ugandan students who use their packages. may not afford Higher Edu- cation HESFB is a body corporate established by an act of Par- liament, number 2 of 2014, to provide loans and scholar- ships to Ugandan students to pursue higher education. The scheme provides loans and scholarships to Ugandan The University department of Students students organised by the office of the Midwifery made a presentation on preven- affairs has urged continuing students to Dean of Students at the Nursing Science tion and management of COVID 19 includ- observe strict adherence to the Standard Lecture Hall on Jan 20th, the Deputy ing a practical demonstration of the correct Operating Procedures (SOPs) set by the Vice Chancellor, Associate Professor way of disinfecting the hands with a hand Ministry of Health so as to stop con- Simon Anguma Katrini urged the stu- rub. -

Speech by Professor Christine Dranzoa Vice

SPEECH BY PROFESSOR CHRISTINE DRANZOA VICE CHANCELLOR DESIGNATE, MUNI UNIVERSITY ON THE OCCASION OF THE GROUND-BREAKING CEREMONY AT MUNI UNIVERSITY “Today knowledge has power. It controls access to opportunity & advancement” DATE: 13TH DECEMBER 2011 VERY SPECIAL GUESTS OF MUNI UNIVERSITY Hon. Minister of Education & Sports, (Chief Guest, Hon Lt. (Rtd) Alupo Jessica Rose Epel (MP) Hon. Minister of Health Dr. Christine Ondoa Hon. Minister of State for Higher Education (Hon. Dr. Chrysostom Muyingo) Hon. Minister of State for Finance (General Duties Hon. Fred Jachan-Omach) Hon. Minister of State for Energy (Hon. Simon D’ujanga) Hon. Minister of State for Internal Affairs Hon. Ambassador James Baba Hon. Members of Parliament, Hon. Simon Ejua (former MP Vuraa County) Permanent Secretary, MoES Vice Chancellor, Gulu University Vice Chancellor, Busitema University Vice Chancellor, Mbarara University of Science & Technology Deputy Vice Chancellor, Makerere University Director, HE/BTVET Commissioner Higher Education The South Korean Team led by Professor H. Kook Park The Contractor (Ms Ambitious Constructions Ltd) The Technical Team from Kampala LCV Chairman: Hon. Sam Nyakua Wadri All Hon. LCVs from West Nile Region RDC, Arua District Your Worship the Mayor for Arua Municipality CAO, Arua District Religious Leaders (My Lord Bishops, The District Khadi) All Principals of Constituent Colleges (Both Public and Private Universities Council Members of NTC, Muni LCI Chairman, Oluko Sub County, Muni Village Elders of Oluko Sub County Muni Village Staff of NTC Muni All chairpersons of Head Teachers Association in West Nile Region Representatives from GIZ, Arua Manager Stanbic Bank, Arua All invited Guests and Dignitaries Colleagues from Muni University Ladies & gentlemen You are all most welcome to this very important occasion, marking the ground breaking for Muni University. -

Report of the Auditor General on the Financial Statements of Muni University for the Year Ended 30Th June 2018

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF MUNI UNIVERSITY FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2018 OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL UGANDA 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................. 2 Key Audit Matters ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Emphasis of matter ................................................................................................................................... 4 Under performance of Non Tax Revenue(NTR) collections ................................................ 4 Other Matter .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Mischarge of expenditure......................................................................................................... 4 Staffing gaps in Academic departments ................................................................................ 5 Undeveloped Land .................................................................................................................... 5 Other Information ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Responsibilities of the Accounting Officer for the Financial Statements ......................................... -

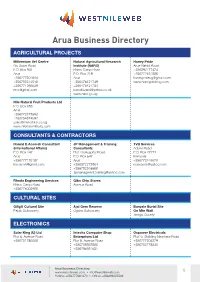

Arua Business Directory.Indd

Arua Business Directory AGRICULTURAL PROJECTS Millennium Vet Centre Natural Agricultural Research Honey Pride Go Down Road Institute (NARO) Arua-Nebbi Road P.O. Box 941 Rhino Camp Road +256392177474 Arua P.O. Box 219 +256772451586 +256777301694 Arua [email protected] +256785514518 +256476421749 www.honeyprideug.com +256771296029 +256476421734 [email protected] [email protected] www.naro.go.ug Nile Natural Fruit Products Ltd P.O. Box 685 Arua +256772373692 +256754374692 [email protected] www.nilenaturalfruits.com CONSULTANTS & CONTRACTORS Harold E.Acemah Consultant JP Management & Training TVB Services (International Affairs) Consultants Adumi Road P.O. Box 147 Plot 10,Hospital Road P.O. Box 27772 Arua P.O. Box 647 Kampala +256777175187 Arua +256772446676 [email protected] +256372273964 [email protected] +256782346688 [email protected] Rhoda Engineering Services Gibo Chip Stores Rhino Camp Road Avenue Road +256776002988 CULTURAL SITES Giligili Cultural Site Ajai Gem Reserve Banyale Burial Site Pajulu Subcounty Ogoko Subcounty On Mtn Wati Terego County ELECTRONICS Solar King (U) Ltd Intechs Computer Shop Ospower Electricals Plot 6, Avenue Road Enterprises Ltd Plot14, Building New lane Road +256751786008 Plot 8, Avenue Road +256777204279 +256758353856 +256752778540 +256786931631 Arua Business Directory www.westnileweb.com • [email protected] 1 Hotline: +256777681670 • Office: +256393225533 Metro Electronics Arua Phones Service Centre Aliza Electronic Ltd Plot 10, Duka Road Plot12, Avenue Road Avenue Road +256702144786 +256772822122 +256715089299 +256713144786 Holly Wood Electronics (U) Roman Electronics (U) Ltd Plot1- 3, Adumi Road Adumi Road +256713144786 +256778134910 FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS Centenary Bank Stanbic Bank Bank of Africa Plot 3, Avenue Road Avenue Road Plot 19, Avenue Road P.O. -

Metropolitan Journal of Business & Economics

Editor in Chief Prof. Austin N. Nosike Metropolitan Journal of Business & Economics Vol. 1, No.1, 2020 METROPOLITAN INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Directorate of Research & Innovations access this journal online at www.miu.ac.ug i Metropolitan Journal of Business and Economics Vol. 1, No. 1, 2020 Editor in Chief Prof. Austin N. Nosike Kampala, Uganda ii ISSN 1813-422X(print) Metropolitan Journal of Business and Economics Vol.1, No.1,2020 ISSN 1813-4238(online) Metropolitan International University Press www.miu.edu.ug Metropolitan Journal of Business and Economics Editorial Board Chairman &Vice Chancellor Dr Julius Arinaitwe Editor in Chief Prof. Austin N. Nosike Associate Editor Production Editor Prof. Nwachukwu Ololube Prof Shobana Nelasco Editorial Assistant Project Advisor Dr. Anthony C. Nwali Prof M.A. Mainoma Serial Editor Business Editor Prof M.N. Modebelu Dr Usman Kibon Ado Scientific Director Language Editor Prof. Jacinta A. Opara Prof. Charles Ayo University Secretary Head of Bureau Dr. Ariyo K. Gracious Dr V.O. Charles -Unadike Journal Manager Coordinator Asiimwe Isaac Kazaara Dr Chidiebere Ogbonna The contents of MIU Journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions or position of the Editorial Boards, Metropolitan International University Press or the Governing Council. Neither Metropolitan International University nor any person acting on its behalf is responsible for the use which may be made of the information in the publication. The views published in the journal are entirely those of the authors. The materials printed in our journal are copyright and should not be reproduced without the written permission of the Directorate of Research. Any dispute that may arise relating to the journal shall be peacefully settled by the parties before an agreed Mediation. -

Programme Code: Smb Muni

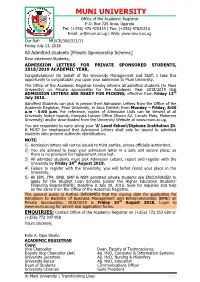

MUNI UNIVERSITY Office of the Academic Registrar P.O. Box 725 Arua, Uganda Tel: (+256) 476 420314 | Fax: (+256) 47620316 Email: [email protected] | Web: www.muni.ac.ug Our Ref: MU/CR/300/311/11 Friday July 13, 2018 All Admitted students [Private Sponsorship Scheme] Dear esteemed Students, ADMISSION LETTERS FOR PRIVATE SPONSORED STUDENTS, 2018/2019 ACADEMIC YEAR. Congratulations! On behalf of the University Management and Staff, I take this opportunity to congratulate you upon your admission to Muni University. The Office of the Academic Registrar hereby informs all admitted students (to Muni University) on Private sponsorship for the Academic Year 2018/2019 that ADMISSION LETTERS ARE READY FOR PICKING; effective from Friday 13th July 2018. Admitted Students can pick in person their Admission Letters from the Office of the Academic Registrar, Muni University, in Arua District; from Monday – Friday, 8:00 a.m - 5:00 p.m. For reference, copies of Admission Lists can be viewed at all University Notice boards, Kampala Liaison Office (Room A2, Lincoln Flats, Makerere University) and/or downloaded from the University Website at www.muni.ac.ug. You are requested to carry along your ‘A’ Level School/Diploma Institution ID. It MUST be emphasized that Admission Letters shall only be issued to admitted students who present authentic identification. NOTE: 1) Admission letters will not be issued to third parties, unless officially authorized. 2) You are advised to keep your admission letter in a safe and secure place; as there is no provision for replacement once lost. 3) All admitted students must pick Admission Letters; report and register with the University by Friday 24th August 2018. -

Ticad Vi Side Event for Female Vice Chancellors From

TICAD VI SIDE EVENT FOR FEMALE VICE CHANCELLORS FROM UNIVERSITIES IN AFRICA Proceedings of the Forum for African Women Vice Chancellors (FAWoVC) Held at Radisson Blu Hotel, Nairobi, Kenya from 22nd to 25 August 2016 Organized by Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology 1 TICAD VI SIDE EVENT FOR FEMALE VICE CHANCELLORS FROM UNIVERSITIES IN AFRICA Proceedings of the Forum for African Women Vice Chancellors (FAWoVC) Held at Radisson Blu Hotel, Nairobi, Kenya from 22nd to 25 August 2016 Organized by Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology 2 © Copyright JKUAT August, 2016 Any part of these proceedings can be reproduced or cited as long as appropriate acknowledgement is made. Compiled by: Prof. Florence K. Lenga Dr. Daniel N. Sila 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The culmination of this Forum for African Women Vice Chancellors would not have been realized without the support of stakeholders who played an instrumental role in either developing the proposal, providing funding or the organizational capacity required. In this regard, the contribution made by all stakeholders is sincerely appreciated. Notably, the Organizing Committee under the auspices of the Vice Chancellor of Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (JKUAT) wishes to recognize the role played by UNESCO, DAAD, RUFORUM, UN Women, JICA, and BECTRUM in the provision of financial and material support for the organization of the Forum. Our appreciation also goes to the resource persons who presented papers and willingly shared their wealth of knowledge and experiences with the participants. On the other hand the Forum would not have been successful without the active and interactive participation of the participants. -

2019 Issn: 2456-8643

International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Bioresearch Vol. 4, No. 05; 2019 ISSN: 2456-8643 COMPLIANCE TO RIVERBANK REGULATION GUIDELINES AND ITS IMPACT ON THE QUALITY OF RIVER ENYAU IN ARUA MUNICIPALITY, UGANDA Geofrey Oloya* and Morgan Andama Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Muni University, P.O.Box 725, Arua, Uganda *Corresponding Author: [email protected] or [email protected] http://doi.org/10.35410/IJAEB.2019.4446 ABSTRACT This study documented the human activities carried out in the protected zones of river Enyau (within 30 m of river’s bank) and their influence on the quality of the river. Human activities in the protected bank of river Enyau and the quality of the river were ascertained during a field survey in March-May, 2019.The diversity of macrozoobenthic invertebrates per site and water pollution levels were determined using Shannon-Weiner (Hʹ) and Biological Monitoring Working Party (BMWP) indices respectively. Fourteen different human activities dominated by housing units (27%) were observed in river Enyau protected zones under study in Arua Municipality. Ozu-Ediofe zone corresponding directly to Arua urban center recorded the highest occurrence of the human activities (65.3%) which greatly reduced the macrozoobenthic invertebrate diversity (Hʹ=1.2) and caused pollution of river Enyau (BMWP=26.0) along that zone. The downstream zones, Onduparaka (Hʹ =2.24, BMWP=68.6) and Onduparaka-Ozu (Hʹ=1.57, BMWP=46.9) sites were both moderately polluted. On the other hand, the upstream zones i.e. Ediofe-Pajulu Bridge (Hʹ=2.52, BMWP=132.9) and Ragem Technical Institute (Hʹ=2.48, BMWP=96.2) were unpolluted and slightly polluted respectively. -

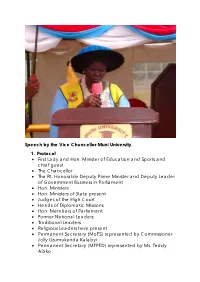

Speech by the Vice Chancellor Muni University. 1. Protocol • First Lady and Hon

Speech by the Vice Chancellor Muni University. 1. Protocol • First Lady and Hon. Minister of Education and Sports and chief guest • The Chancellor • The Rt. Honorable Deputy Prime Minister and Deputy Leader of Government Business in Parliament • Hon. Ministers • Hon. Ministers of State present • Judges of the High Court • Heads of Diplomatic Missions • Hon. Members of Parliament • Former National Leaders • Traditional Leaders • Religious Leaders here present • Permanent Secretary (MoES) represented by Commissioner Jolly Uzumukunda Kalabyi • Permanent Secretary (MFPED) represented by Ms. Teddy Alako • Chairman of Council and Council Members • Members of Senate • The Vice Chancellors of Sister Universities • The Deputy Vice Chancellors • District Chairpersons • Resident District Commissioners • Local leaders • Academic Registrars here present • All Civic Leaders here present • Parents and Guardians • Muni University Alumni • The Guild President • Staff of Muni University • Graduands • Special Guests • The Media • My Colleagues, Muni University Awards and Ceremonies Committee • Ladies and Gentlemen, 2. Welcome Remarks The Hon. Minister of Education and Sports, The Chancellor, Distinguished invited Guests, Graduands, Parents Guardians, Ladies and Gentlemen. I am greatly honored to welcome you all to the 2nd Congregation of Muni University, this 3rd Day of November 2018. 3. Brief Historical Background As you may all be aware, the establishment of Muni University dates back to December 2009, when the Minister of Education and Sports appointed a three-member task force led by the Vice Chancellor, to begin the process of starting a public University in the region without necessarily inheriting any facility from any institution. I will always be happy to report that the task force did a commendable job by securing land, putting in place the necessary arrangements and documentation including the master plan to mention but a few. -

RECOGNISED TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES No Insititutions Name and Address 1 Makerere University P.O. Box 7062, Kamp

RECOGNISED TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES No Insititutions Name and Address 1 Makerere University P.O. Box 7062, Kampala www.muk.ac.ug 2 Mbarara University of Science and Technology P.O. Box 1410, Mbarara www.must.ac.ug 3 Gulu University P.O. Box 166, Gulu www.gu.ac.ug/ 4 Kyambogo University P.O. Box 1, Kyambogo www.kyu.ac.ug 5 Busitema University P.O. Box 236, Tororo htp://busitema.ac.ug/ 6 Muni University P.O.Box 725, Arua Email: [email protected] www.muni.ac.ug 7 Kabale University P.O. Box 317, Kabale, Kikungiri 8 Lira University Plot 1162, Ayere Barapwo P.O.Box 1035, Lira Tel: 0471660714 8 Soroti University Plot 50 & 51 Arapai P.O.Box 211, Soroi Tel: 0454461605 www.su.ac.ug PUBLIC UNIVERSITY COLLEGES No Insituions Name and Address 1 Makerere University Business School P.O. Box 7062 Kampala, Uganda. Tel: +256-41- 32752/530231/5302232. Website: htp://mak.ac.ug. Fax: +256 -41 533640/ 541068. 2 Makerere University College of Health Sciences P.O. Box 7062, Kampala htp://chs.mak.ac.ug/ 3 Makerere University College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences P.O. Box 7062, Kampala htp://sas.mak.ac.ug/ 4 Makerere University College of Business and Management Science P.O. Box 7062, Kampala htp://bams.mak.ac.ug 4 Makerere University College of Compuing and Informaion Sciences P.O. Box 7062, Kampala htp://cis.mak.ac.ug 5 Makerere University College of Educaion and External Studies P.O. Box 7062, Kampala htp://cees.mak.ac.ug 6 Makerere University College of Engineering, Design, Art & Technology P.O. -

CUUL Members – 2020

CUUL Members – 2020 University Libraries 1. African Bible University 2. African Rural University 3. Aga Khan University 4. Bishop Barham University College of UCU 5. Bugema University 6. Busitema University 7. Cavendish University 8. Clarke International University 9. Entebbe International University 10. Gulu University 11. FINS Medical University 12. International University of East Africa 13. ISBAT University 14. Islamic University in Uganda 15. Kabale University 16. Kampala International University 17. Kampala University 18. Kumi University 19. Kyambogo University 20. Lira University 21. Makerere University 22. Makerere University Business School 23. Mbarara University of Science & Technology 24. Metropolitan International University 25. Mountains of the Moon University 26. Muni University 27. Ndejje University 28. Nile University Arua 29. Nkumba University 30. Team University 31. Uganda Christian University 32. Uganda Martyrs University 33. University of Kisubi 34. Victoria University 35. Virtual University Degree awarding institutions 36. Ernest Cook Ultrasound Research and Education Institute 37. HOSPICE Africa 38. Institute of Petroleum Studies - Kampala 39. Uganda Catholic Management & Training Institute 40. Uganda Management Institute 41. YMCA Comprehensive Institute College, training centre, Research, public and government parastatal Libraries 42. Bank of Uganda 43. Electricity Regulatory Authority 44. Kampala Capital City Authority Library 45. Nsambya School of Nursing 46. National Planning Authority 47. National Teachers College – Unyama 48. Office of the Auditor General 49. Parliament of Uganda 50. Public Procurement and Disposal of Public Assets Authority 51. Reformed Theological College – Bunamwaya 52. St. John the Baptist – Ggaba PTC 53. The Insurance Institute of Uganda 54. Uganda Information and Communication Technology Institute 55. Uganda National Examinations Board 56.