How Criminal Organizations Expand to Strong States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organized Crime and Electoral Outcomes. Evidence from Sicily at the Turn of the XXI Century

Organized Crime and Electoral Outcomes. Evidence from Sicily at the Turn of the XXI Century Paolo Buonanno,∗ Giovanni Prarolo (corresponding author),y Paolo Vaninz November 4, 2015 Abstract This paper investigates the relationship between Sicilian mafia and politics by fo- cusing on municipality-level results of national political elections. It exploits the fact that in the early 1990s the Italian party system collapsed, new parties emerged and mafia families had to look for new political allies. It presents evidence, based on disaggregated data from the Italian region of Sicily, that between 1994 and 2013 Silvio Berlusconi’s party, Forza Italia, obtained higher vote shares at national elec- tions in municipalities plagued by mafia. The result is robust to the use of different measures of mafia presence, both contemporary and historical, to the inclusion of different sets of controls and to spatial analysis. Instrumenting mafia’s presence by determinants of its early diffusion in the late XIX century suggests that the correla- tion reflects a causal link. Keywords: Elections, Mafia-type Organizations JEL codes: D72, H11 ∗Department of Economics, University of Bergamo, Via dei Caniana 2, 24127 Bergamo, Italy. Phone: +39- 0352052681. Email: [email protected]. yDepartment of Economics, University of Bologna, Piazza Scaravilli 2, 40126 Bologna, Italy. Phone: +39- 0512098873. E-mail: [email protected] zDepartment of Economics, University of Bologna, Piazza Scaravilli 2, 40126 Bologna, Italy. Phone: +39- 0512098120. E-mail: [email protected] 1 1. Introduction The relationship between mafia and politics is a crucial but empirically under-investigated issue. In this paper we explore the connection between mafia presence and party vote shares at national political elections, employing municipality level data from the mafia-plagued Italian region of Sicily. -

IL DOSSIER X

pagina 4 Giovedì 10 dicembre 2009 x IL DOSSIER x di Marco Lillo quello che volevamo e avevamo il paese le stragi del 1993 quando, mentre mette- stelle nel quale si organizzavano le prime Alla vigilia della deposizione dei capimafia, nelle mani. Mi disse che le persone che ci vano le bombe a Roma, Firenze e Milano, convention di Forza Italia. “B. ci ha dato E NON ARRIVA avevano dato garanzie erano serie, a uccidendo, giravano i posti più belli d’Italia Altri immobili per 50 milioni di euro sono stati niente da dove deve differenza dei socialisti, e mi fece i nomi di aiutati (magari involontariamente) da una confiscati a un altro referente dei Graviano, la sentenza di I° grado ricostruisce arrivare è il caso che Silvio Berlusconi e di Marcello Dell’Utr i”. I serie di personaggi legati aella famiglia quel Giuseppe Cosenza che è stato cliente cominciamo a parlare Graviano hanno già smentito le sue parole dell’ex manager di Publitalia, e attuale sot- dell'attuale presidente del senato, l'avvocato il Paese”: “Sanche noi con i magistrati”. Questa frase davanti ai pm di Firenze. Ora ci provano tosegretario Gianfranco Micciché, o in rap- Renato Schifani. Ai boss hanno sequestrato gli intrecci del braccio attribuita dal pentito Gaspare Spatuzza a quelli di Palermo, incuriositi dallo strano porti con Marcello Dell’Utri (ora senatore e anche un impianto da 5 milioni di euro adi- Filippo e Giuseppe Graviano, i suoi capi, atteggiamento dei due boss che non hanno allora capo di Publitalia). Quando si parla dei bito a torrefazione e zuccherificio. -

Download Clinton Email June Release

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No. C05761507 Date: 06/30/2015 RELEASE IN PART B6 From: H <[email protected]> Sent: Tuesday, December 15, 2009 12:25 PM To: '[email protected]' Subject: Fw: H: Memo, idea on Berlusconi attack. Sid Attachments: hrc memo berlusconi 121509.docx Pls print. Original Message From: sbwhoeop To: H Sent: Tue Dec 15 10:43:11 2009 Subject: H: Memo, idea on Berlusconi attack. Sid CONFIDENTIAL December 15, 2009 For: Hillary From: Sid Re: The Berlusconi assault 1. The physical attack on Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi is a major political event in Italy and Europe. His assailant is a mentally disturbed man without a political agenda who has been in and out of psychiatric care since he was 18 years old. Nonetheless, the assault has significant repercussions. It has generated sympathy for Berlusconi as a victim—he has been obviously injured, lost two teeth and a pint of blood, and doctors will keep him in the hospital for perhaps a week for observation. The attack comes as Berlusconi was beginning to lose political footing, having lost his legal immunity. One court inquiry is turning up evidence of his links to the Mafia while another is examining his role in the bribery case of British lawyer David Mills. Berlusconi's government and party have used the attack as a way to turn the sudden sympathy for him to his advantage, claiming that his opponents have sown a climate of "hate." Through demogogic appeals they are attempting to discredit and rebuff the legal proceedings against him and undermine the investigative press. -

LE MENTI RAFFINATISSIME Di Paolo Mondani E Giorgio Mottola

1 LE MENTI RAFFINATISSIME Di Paolo Mondani e Giorgio Mottola Collaborazione Norma Ferrara, Alessia Pelagaggi e Roberto Persia Immagini Dario D’India, Alfredo Farina e Alessandro Spinnato Montaggio e grafica Giorgio Vallati GIUSEPPE LOMBARDO - PROCURATORE AGGIUNTO TRIBUNALE DI REGGIO CALABRIA Licio Gelli era il perno. Perché attraverso la P2 lui controllava i Servizi. GIANMARIO FERRAMONTI - EX POLITICO LEGA NORD Essere lontani da Cosa Nostra se si agisce in Sicilia è molto difficile. CONSOLATO VILLANI - COLLABORATORE DI GIUSTIZIA Dietro le stragi c'erano i servizi segreti deviati GIOACCHINO GENCHI - EX UFFICIALE POLIZIA DI STATO La principale intenzione era quella di non trovare i veri colpevoli. PIETRO RIGGIO - COLLABORATORE DI GIUSTIZIA - 19/10/2020 PROCESSO D'APPELLO TRATTATIVA STATO-MAFIA L'indicatore dei luoghi dove erano avvenute le stragi fosse stato Marcello Dell'Utri. ROBERTO TARTAGLIA – EX PM PROCESSO TRATTATIVA STATO-MAFIA Chi è che insegna a Salvatore Riina il linguaggio che abbina la cieca violenza mafiosa alla raffinata guerra psicologica di disinformazione che c’è dietro l'operazione della Fa- lange Armata? NINO DI MATTEO - MAGISTRATO PROCESSO TRATTATIVA - MEMBRO CSM È successo anche questo, scoprire che un presidente della Repubblica aveva mentito. SILVIO BERLUSCONI - EX PRESIDENTE DEL CONSIGLIO Io su indicazione dei miei avvocati intendo avvalermi della facoltà di non rispondere. SIGFRIDO RANUCCI IN STUDIO Buonasera, parleremo del periodo stragista che va dal 1992 al 1994, della presunta trattativa tra Stato e Mafia. Lo faremo con documenti e testimonianze inedite, tra le quali quella di Salvatore Baiardo, l’uomo che ha gestito la latitanza dei fratelli Graviano, una potente famiglia mafiosa, oggi accusata di essere l’autrice della strage di via d’Ame- lio. -

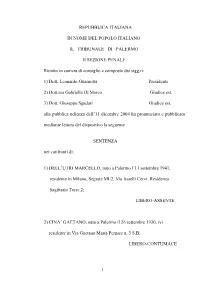

Sentenza.Pdf

REPUBBLICA ITALIANA IN NOME DEL POPOLO ITALIANO IL TRIBUNALE DI PALERMO II SEZIONE PENALE Riunito in camera di consiglio e composto dai sigg.ri: 1) Dott. Leonardo Guarnotta Presidente 2) Dott.ssa Gabriella Di Marco Giudice est. 3) Dott. Giuseppe Sgadari Giudice est. alla pubblica udienza dell’11 dicembre 2004 ha pronunciato e pubblicato mediante lettura del dispositivo la seguente SENTENZA nei confronti di: 1) DELL’UTRI MARCELLO, nato a Palermo l’11 settembre 1941, residente in Milano, Segrate MI/2, Via fratelli Cervi, Residenza Sagittario Torre 2; LIBERO-ASSENTE 2) CINA’ GAETANO, nato a Palermo il 26 settembre 1930, ivi residente in Via Gaetano Maria Pernice n. 3 S.B. LIBERO-CONTUMACE 1 IMPUTATI DELL’UTRI MARCELLO A) del delitto di cui agli artt. 110 e 416 commi 1, 4 e 5 c.p., per avere concorso nelle attività della associazione di tipo mafioso denominata “Cosa Nostra”, nonché nel perseguimento degli scopi della stessa, mettendo a disposizione della medesima associazione l’influenza ed il potere derivanti dalla sua posizione di esponente del mondo finanziario ed imprenditoriale, nonché dalle relazioni intessute nel corso della sua attività, partecipando in questo modo al mantenimento, al rafforzamento ed alla espansione della associazione medesima. E così ad esempio: 1. partecipando personalmente ad incontri con esponenti anche di vertice di Cosa Nostra, nel corso dei quali venivano discusse condotte funzionali agli interessi della organizzazione; 2. intrattenendo, inoltre, rapporti continuativi con l’associazione per delinquere tramite numerosi esponenti di rilievo di detto sodalizio criminale, tra i quali Bontate Stefano, Teresi Girolamo, Pullarà Ignazio, Pullarà Giovanbattista, Mangano Vittorio, Cinà Gaetano, Di Napoli Giuseppe, Di Napoli Pietro, Ganci Raffaele, Riina Salvatore; 3. -

"I Soldi Della Droga a Berlusconi"

IL PENTITO GAETANO GRADO "I soldi della droga a Berlusconi" Martedì 30 Ottobre 2012 - 18:12 Processo Dell'Utri. Depone il pentito Gaetano Grado e dice: "I soldi del narcotraffico sono stati investiti nelle attività economiche di Berlusconi". ROMA- Negli anni '70 un flusso di denaro proveniente dai traffici di droga di Cosa nostra sarebbe stato investito nelle attività economiche "Milano 1 e Milano 2", di Silvio Berlusconi. Lo ha raccontato il pentito Gaetano Grado deponendo, nell'aula bunker del carcere romano di Rebibbia, al processo d'appello per concorso in associazione mafiosa al senatore del Pdl Marcello Dell'Utri. Grado, citato dal procuratore generale dopo essere stato interrogato dai pm di Palermo ad agosto, ha anche parlato dei rapporti tra il boss Vittorio Mangano, poi assunto nella villa di Arcore dell'ex premier come stalliere, e Dell'Utri. "Mangano mi rispettava e chiese a me il permesso di andare ad Arcore a lavorare. So che a interessarsi per farlo andare lì erano stati Tanino Cinà (altro capomafia ndr) e Dell'Utri". Dei viaggi a Milano di Mangano, che avrebbe portato i soldi del narcotraffico accumulati dalle famiglie mafiose a Dell'Utri perché li investisse nelle attività di Berlusconi, Grado avrebbe saputo dallo stesso "stalliere" e dal fratello Antonino. Il pentito, che solo nel 2012 ha parlato della vicenda, nonostante più volte sia stato sentito dai pm, non ha saputo indicare, però, circostanze più precise: "Quando si trattava di droga - ha detto - non facevo domande perché la cosa mi ripugnava". Il collaboratore ha anche raccontato che nel 1980 i boss, con l'aiuto di Mangano, misero una bomba davanti al cancello della villa di Arcore come atto dimostrativo. -

Alexanderstille:Giuffrè?Maperchédell

sabato 11 gennaio 2003 oggi 5 Federica Fantozzi messi viaggiatori? Un altro pentito, Francesco De Carlo, ha detto che Del- l’Utri era andato al suo matrimonio a ROMA Alexander Stille, giornalista e È compito Negli Usa anni 40 era Londra. C’erano pure le foto. Lui ha scrittore, vive a New York. Collabora detto: ero lì per caso, mi portava un con diverse testate fra cui New York amico. Ma è credibile che un siciliano dell’accusa trovare impensabile condannare ‘‘ Times e New Yorker. È autore di un navigato si presenti a un matrimonio libro sulla mafia siciliana pubblicato riscontri e conferme un uomo di mafia. Grazie ai dove c’è il gotha mafioso senza saper- da Mondadori nel ‘95 con il titolo Nel- lo? Poi c’è un’altra cosa: in Italia si ten- la terra degli infedeli. alle dichiarazioni del pentito pentiti è stato possibile capire de a confondere le testimonianze diret- Negli Usa John Gotti era consi- ‘‘ te con quelle indirette». derato un “intoccabile” finché è Ma spesso è l’unico le regole interne e battere Le ultime di Giuffrè erano indi- caduto per le dichiarazioni di rette: cose sapute da Michele uno dei suoi uomini diventato a conoscere certi fatti il fenomeno mafioso Greco, da Giovanni Brusca. collaboratore di giustizia. Come «Questo tipo di rivelazioni ha un è andata? peso minore. Da sole non basterebbe- «Gotti è stato ro. Vanno però incastrato da un valutate nel conte- insieme di cose. sto. Con le inter- Certo, la più im- cettazioni telefo- portante è la testi- niche, le foto, tut- monianza di Sam- to». -

Processo Dell'utri 2010-2012

PROCURA GENERALE DELLA REPUBBLICA PRESSO LA CORTE D’APPELLO DI PALERMO Requisitoria del P.G. nel procedimento a carico di Dell’Utri Marcello, imputato del reato p.e.p. dagli artt.110,416 bis c.p. I LE QUESTIONI PROCESSUALI 1)Nullità della sentenza per genericità dell’accusa Spia visibile della denunciata indeterminatezza del capo di imputazione sarebbe il fatto che al cappello (costituito da quella parte della rubrica in cui sono enunciati i comportamenti generici ascritti all’imputato) seguono degli esempi di fatti specifici, che però per la difesa specifici non sarebbero e dimostrerebbero che la tecnica seguita dal PM tende a far riempire dal dibattimento degli schemi vuoti preliminarmente costruiti. E’ evidente che si tratta di eccezione formulata per scrupolo difensivo, del tutto apodittica e internamente contraddittoria nella parte in cui non tiene conto del fatto che formulare esempi costituisce esercizio di concretezza, salvo stabilire se le condotte esemplificate siano provate o non. Il requirente si limita a ricordare che la contestazione non è costituita dal solo capo di imputazione, ma dal complesso degli elementi di accusa, emersi anche nel corso del dibattimento, che sono stati portati a conoscenza del prevenuto e sui quali egli è stato posto in condizione di esercitare la propria difesa. Inoltre, si richiama quanto rilevato dal primo giudice nell’ordinanza 18\11\97 con cui l’eccezione fu rigettata: che la natura di reato a forma libera del delitto di cui all’art.416 bis impedisce “di ripercorrere singolarmente le numerose condotte che formeranno oggetto di accertamento, essendo questa operazione incompatibile con la necessaria sintesi che deve guidare la redazione del capo di imputazione”. -

Vent'anni Da Picciotto

RC Auto? chiama gratis 800-070762 www.linear.it Mercoledì 30 www.unita.it 1,20E Giugno 2010 Anno 87 n. 178 Tutta l’Italia va diventando Sicilia. Dicono che la linea della palma, il clima propizio, viene su, verso nord, di cinquecento metri ogni anno. Io invece dico: questa linea della palma, del caffè forte, degli scandali: su su per l’Italia, ed è già oltre Roma... Leonardo Sciascia, «Il giorno della civetta» OGGI“ CON NOI... Claudio Fava, Igiaba Scego, Giuseppe Civati, Filippo Di Giacomo, Nicola Tranfaglia VENT’ANNI DA PICCIOTTO ...e sette anni di carcere Ma Mangano resta «un eroe» La politica di Cosa Nostra Marcello Dell’Utri condannato Il cofondatore di Forza Italia Rita Borsellino: «Ora è provato: in appello per «concorso esterno teneva rapporti con Riina la mafia nelle fondamenta del Pdl» in associazione mafiosa» Bontate e Provenzano La maggioranza esulta, la Lega tace Marcello Dell’Utri, la piazza di Corleone e in alto da sinistra Stefano Bontate, Vittorio Mangano e la carta di identità di Totò Riina p ALLE PAGINE 4-11 L’addio a Taricone Mobilitazione La gente parte Roberto Saviano: in tutta Europa E il governo «Noi, compagni contro la legge aumenta i pedaggi di scuola» bavaglio Autostrade Da domani incrementi Se ne va a 35 anni Sit in Domani alle 17 fino al 5%. Le mani nelle tasche degli L’uomo e il suo destino manifestazione in piazza italiani p A PAGINA 30 p ALLE PAGINE 12-15 Navona p ALLE PAGINE 22-23 2 www.unita.it MERCOLEDÌ 30 GIUGNO 2010 Diario NICOLA TRANFAGLIA Storico Oggi nel giornale PAG. -

Con Sentenza Dell'11 Dicembre 2004 Il Tribunale Di Palermo Dichiarava Marcello Dell'utri Colpevole Dei Reati A) Di Cui Agli

LA SENTENZA DI PRIMO GRADO Con sentenza dell’11 dicembre 2004 il Tribunale di Palermo dichiarava Marcello Dell’Utri colpevole dei reati A) di cui agli artt.110 e 416 commi 1, 4 e 5 c.p. per avere concorso nelle attività della associazione di tipo mafioso denominata “Cosa Nostra”, nonché nel perseguimento degli scopi della stessa, mettendo a disposizione della medesima associazione l’influenza ed il potere derivanti dalla sua posizione di esponente del mondo finanziario ed imprenditoriale, nonché dalle relazioni intessute nel corso della sua attività, partecipando in questo modo al mantenimento, al rafforzamento ed alla espansione della associazione medesima. E così ad esempio: 1. partecipando personalmente ad incontri con esponenti anche di vertice di Cosa Nostra, nel corso dei quali venivano discusse condotte funzionali agli interessi della organizzazione; 2. intrattenendo, inoltre, rapporti continuativi con l’associazione per delinquere tramite numerosi esponenti di rilievo di detto sodalizio criminale, tra i quali Bontate Stefano, Teresi Girolamo, Pullarà Ignazio, Pullarà Giovanbattista, Mangano Vittorio, Cinà Gaetano, Di Napoli Giuseppe, Di Napoli Pietro, Ganci Raffaele, Riina Salvatore; 3. provvedendo a ricoverare latitanti appartenenti alla detta organizzazione; 4. ponendo a disposizione dei suddetti esponenti di Cosa Nostra le 1 conoscenze acquisite presso il sistema economico italiano e siciliano. Così rafforzando la potenzialità criminale dell’organizzazione in quanto, tra l’altro, determinava nei capi di Cosa Nostra ed in altri suoi aderenti la consapevolezza della responsabilità di esso Dell’Utri a porre in essere (in varie forme e modi, anche mediati) condotte volte ad influenzare – a vantaggio della associazione per delinquere – individui operanti nel mondo istituzionale, imprenditoriale e finanziario. -

Renzi: «Lotta Violenta Alla Burocrazia»

A fallire in Ruanda non è stata solo l’Onu: abbiamo fallito anche noi giornalisti che non abbiamo prestato attenzione a quanto stava accadendo o abbiamo scritto solo frasi fatte. Bartholomaus Grill Der Spiegel 2,30 l'Unità+Left (non vendibili separatamente - l'Unità 1,30 euro - Left 1,00 euro) Anno 91 n. 100 - Sabato 12 Aprile 2014 Essere marxisti Sarti, detective Gunter Pauli: Gli inediti «La mia carta di Bobbio da 40 anni è una roccia» U: Gravagnuolo a pag. 18 Macchiavelli pag. 17 Perugini pag. 19 Dell’Utri beffa la giustizia ● L’ex senatore Pdl e consigliere di Berlusconi si rende latitante all’estero alla vigilia della Cassazione ● È accusato di mafia, in Appello condannato a 7 anni ● Dice: «Mi sto curando» ● È polemica sulla fuga Marcello Dell’Utri è ufficialmente lati- tante. L’ex senatore Pdl è fuggito LE INTERVISTE all’estero alla vigilia della sentenza del- la Cassazione sul processo per mafia. È giallo sul passaporto utilizzato. BUFALINI LOMBARDO A PAG. 2-3 Orlando: L’ultimo atto ecco il piano di un ventennio per legalità e carceri MASSIMO ADINOLFI DELL’UTRI LATITANTE. BERLUSCO- ● NI AI SERVIZI SOCIALI. FORMIGONI ALLE PRESE COL SEQUESTRO DI BENI (POSSEDUTI PERÒ A SUA INSAPUTA). CO- SENTINO, INFINE, NUOVAMENTE IN CAR- CERE. È dai tempi di Tangentopoli che l’Italia si ritrova tra i piedi il se- guente problema: come evitare di scrivere la storia politica del Paese senza mutarla in una storia crimina- le, in un commento a piè di pagina Al via la legge sull’autoriciclaggio e delle sentenze della magistratura. -

I" T R I B U N a L E D I P a L E R M O Sezione Corte Di Assise

I I 1870~ I" T R I B U N A L E D I P A L E R M O SEZIONE CORTE DI ASSISE t UDIENZA DEL 04 Maggio 1994 • ====================================== PROCESSO CONTRO: GRECO MICHELE + ALTRI ====================================== Bobina n.1 T R A S C R I Z I O N E U D I E N Z A ========================================== • Perito, Lo Verde Vincenza Via Giovanni Prati n.15 Palermo 1 J ~.- I~. ~. ----------------,---- 18705 PRESIDENTE: Facciamo la costituzione dei difensori ... vedo in aula i rappresentanti delle Parti Civili, avvocat.o Sorrent.ino, l~avvocato Grosso, per la Parte Civile P.D.S, l'avvocato Avellone per la Parte Civile Di Salvo, l'avvocato dell'Aira e l'avvo~ato • Arnone per l'Avvocatura dello Stato. Il preliminarmente, poichè DCCOI-re alla registrazion~ della udienza, ed • informato del fatto che l'aula è dotata anche di dispositivo per la regist.razione audiovisivo, da l'incarico di alle relatiVE? operazioni tecniche al • MAXITELLI , Ma" itell i Giuseppe- na~,o i l 31.01.1944 a Senosecchia Trieste, residente a Bologna via Vasto de Gama n.l. l 18708 PRES-IDENTE, Il quale presta il giurament.o di ,-i to. MAXI TELLI , (Legge la formula di rito) F'RESIDENTE, Dichiara i suoi elaborati seduta stante. MAXITELLI, F'rego. PRESIDENTE, F'ossìamo Salva.tore Cangemi. Gli operatori della stampa • naturalmente sono al corrente che è vietata di •• immagini della persona che verrà a depon-e. Lei è Cangemi Salvatore? CANGEMI S., Si. PRESIDENTE, Vuole ripetere le sue generalità nel microfono .. CANGEMI S., Cangemi Salvatore nato a Palermo il 19.03.1942.