Sociolinguistic Documentation of Language Shift and Maintenance in Iyasa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Referred to As Class 18A (See Hyman 1980:187)

WS1 Remarks on the nasal classes in Mungbam and Naki Mungbam and Naki are two non-Grassfields Bantoid languages spoken along the northwest frontier of the Grassfields area to the north of the Ring languages. Until recently, they were poorly described, but new data reveals them to show significant nasal noun class patterns, some of which do not appear to have been previously noted for Bantoid. The key patterns are: 1. Like many other languages of their region (see Good et al. 2011), they make productive use of a mysterious diminutive plural prefix with a form like mu-, with associated concords in m, here referred to as Class 18a (see Hyman 1980:187). 2. The five dialects of Mungbam show a level of variation in their nasal classes that one might normally expect of distinct languages. a. Two dialects show no evidence for nasals in Class 6. Two other dialects, Munken and Ngun, show a Class 6 prefix on nouns of form a- but nasal concords. In Munken Class 6, this nasal is n, clearly distinct from an m associated with 6a; in Ngun, both 6 and 6a are associated with m concords. The Abar dialect shows a different pattern, with Class 6 nasal concords in m and nasal prefixes on some Class 6 nouns. b. The Abar, Biya, and Ngun dialects show a Class 18a prefix with form mN-, rather than the more regionally common mu-. This reduction is presumably connected to perseveratory nasalization attested throughout the languages of the region with a diachronic pathway along the lines of mu- > mũ- > mN- perhaps providing a partial example for the development of Bantu Class 9/10. -

Linguapax Review 2010 Linguapax Review 2010

LINGUAPAX REVIEW 2010 MATERIALS / 6 / MATERIALS Col·lecció Materials, 6 Linguapax Review 2010 Linguapax Review 2010 Col·lecció Materials, 6 Primera edició: febrer de 2011 Editat per: Amb el suport de : Coordinació editorial: Josep Cru i Lachman Khubchandani Traduccions a l’anglès: Kari Friedenson i Victoria Pounce Revisió dels textos originals en anglès: Kari Friedenson Revisió dels textos originals en francès: Alain Hidoine Disseny i maquetació: Monflorit Eddicions i Assessoraments, sl. ISBN: 978-84-15057-12-3 Els continguts d’aquesta publicació estan subjectes a una llicència de Reconeixe- ment-No comercial-Compartir 2.5 de Creative Commons. Se’n permet còpia, dis- tribució i comunicació pública sense ús comercial, sempre que se’n citi l’autoria i la distribució de les possibles obres derivades es faci amb una llicència igual a la que regula l’obra original. La llicència completa es pot consultar a: «http://creativecom- mons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/es/deed.ca» LINGUAPAX REVIEW 2010 Centre UNESCO de Catalunya Barcelona, 2011 4 CONTENTS PRESENTATION Miquel Àngel Essomba 6 FOREWORD Josep Cru 8 1. THE HISTORY OF LINGUAPAX 1.1 Materials for a history of Linguapax 11 Fèlix Martí 1.2 The beginnings of Linguapax 14 Miquel Siguan 1.3 Les débuts du projet Linguapax et sa mise en place 17 au siège de l’UNESCO Joseph Poth 1.4 FIPLV and Linguapax: A Quasi-autobiographical 23 Account Denis Cunningham 1.5 Defending linguistic and cultural diversity 36 1.5 La defensa de la diversitat lingüística i cultural Fèlix Martí 2. GLIMPSES INTO THE WORLD’S LANGUAGES TODAY 2.1 Living together in a multilingual world. -

November 2011 EPIGRAPH

République du Cameroun Republic of Cameroon Paix-travail-patrie Peace-Work-Fatherland Ministère de l’Emploi et de la Ministry of Employment and Formation Professionnelle Vocational Training INSTITUT DE TRADUCTION INSTITUTE OF TRANSLATION ET D’INTERPRETATION AND INTERPRETATION (ISTI) AN APPRAISAL OF THE ENGLISH VERSION OF « FEMMES D’IMPACT : LES 50 DES CINQUANTENAIRES » : A LEXICO-SEMANTIC ANALYSIS A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of a Vocational Certificate in Translation Studies Submitted by AYAMBA AGBOR CLEMENTINE B. A. (Hons) English and French University of Buea SUPERVISOR: Dr UBANAKO VALENTINE Lecturer University of Yaounde I November 2011 EPIGRAPH « Les écrivains produisent une littérature nationale mais les traducteurs rendent la littérature universelle. » (Jose Saramago) i DEDICATION To all my loved ones ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Immense thanks goes to my supervisor, Dr Ubanako, who took out time from his very busy schedule to read through this work, propose salient guiding points and also left his personal library open to me. I am also indebted to my lecturers and classmates at ISTI who have been warm and friendly during this two-year programme, which is one of the reasons I felt at home at the institution. I am grateful to IRONDEL for granting me the interview during which I obtained all necessary information concerning their document and for letting me have the book at a very moderate price. Some mistakes in this work may not have been corrected without the help of Mr. Ngeh Deris whose proofreading aided the researcher in rectifying some errors. I also thank my parents, Mr. -

Trilingual Codeswitching in Kenya – Evidence from Ekegusii, Kiswahili, English and Sheng

Trilingual Codeswitching in Kenya – Evidence from Ekegusii, Kiswahili, English and Sheng Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde des Doktors der Philosophie der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Nathan Oyori Ogechi aus Kenia Hamburg 2002 ii 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Mechthild Reh 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Ludwig Gerhardt Datum der Disputation: 15. November 2002 iii Acknowledgement I am indebted to many people for their support and encouragement. It is not possible to mention all by name. However, it would be remiss of me not to name some of them because their support was too conspicuous. I am bereft of words with which to thank my supervisor Prof. Dr. Mechthild Reh for accepting to supervise my research and her selflessness that enabled me secure further funding at the expiry of my one-year scholarship. Her thoroughness and meticulous supervision kept me on toes. I am also indebted to Prof. Dr. Ludwig Gerhardt for reading my error-ridden draft. I appreciate the support I received from everybody at the Afrika-Abteilung, Universität Hamburg, namely Dr. Roland Kießling, Theda Schumann, Dr. Jutta Becher, Christiane Simon, Christine Pawlitzky and the institute librarian, Frau Carmen Geisenheyner. Professors Myers-Scotton, Kamwangamalu, Clyne and Auer generously sent me reading materials whenever I needed them. Thank you Dr. Irmi Hanak at Afrikanistik, Vienna, Ndugu Abdulatif Abdalla of Leipzig and Bi. Sauda Samson of Hamburg. I thank the DAAD for initially funding my stay in Deutschland. Professors Miehe and Khamis of Bayreuth must be thanked for their selfless support. I appreciate the kind support I received from the Akademisches Auslandsamt, University of Hamburg. -

A Grammar of Gyeli

A Grammar of Gyeli Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) eingereicht an der Kultur-, Sozial- und Bildungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin von M.A. Nadine Grimm, geb. Borchardt geboren am 28.01.1982 in Rheda-Wiedenbrück Präsident der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr. Jan-Hendrik Olbertz Dekanin der Kultur-, Sozial- und Bildungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät Prof. Dr. Julia von Blumenthal Gutachter: 1. 2. Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: Table of Contents List of Tables xi List of Figures xii Abbreviations xiii Acknowledgments xv 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The Gyeli Language . 1 1.1.1 The Language’s Name . 2 1.1.2 Classification . 4 1.1.3 Language Contact . 9 1.1.4 Dialects . 14 1.1.5 Language Endangerment . 16 1.1.6 Special Features of Gyeli . 18 1.1.7 Previous Literature . 19 1.2 The Gyeli Speakers . 21 1.2.1 Environment . 21 1.2.2 Subsistence and Culture . 23 1.3 Methodology . 26 1.3.1 The Project . 27 1.3.2 The Construction of a Speech Community . 27 1.3.3 Data . 28 1.4 Structure of the Grammar . 30 2 Phonology 32 2.1 Consonants . 33 2.1.1 Phonemic Inventory . 34 i Nadine Grimm A Grammar of Gyeli 2.1.2 Realization Rules . 42 2.1.2.1 Labial Velars . 43 2.1.2.2 Allophones . 44 2.1.2.3 Pre-glottalization of Labial and Alveolar Stops and the Issue of Implosives . 47 2.1.2.4 Voicing and Devoicing of Stops . 51 2.1.3 Consonant Clusters . -

Curriculum Vitae

KRISTINE A. HILDEBRANDT Professor Department of English Language and Literature Website: http://www.siue.edu/~khildeb Co-Director IRIS Digital Humanities Center https://iris.siue.edu/ E-mail: [email protected] Updated: June 2021 EDUCATION Ph.D., Linguistics, University of California Santa Barbara, 2003 (Dissertation Title: Manange Tone: Scenarios of Retention & Loss in Two Communities; Dissertation Supervisor: Carol Genetti; Committee Members: Matthew Gordon, Marianne Mithun, Michael Noonan) M.A., English with Linguistics Concentration, Arizona State University, 1997 (Thesis Title: Minimalism, Functional Categories & O’odham Word Order Patterns; Thesis Supervisor: Elly van Gelderen; Committee Members: Karen Adams, Leonard Faltz) B.A., English (Philosophy minor), Keene State College, NH, 1992 ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS July 2019-continuing Professor, Department of English, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville July 2012-continuing Associate Professor, Department of English, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville 2008-June 2012 Assistant Professor, Department of English, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville 2005-2008 Lecturer, Linguistics & English Language, University of Manchester, England 2003-2005 Post-Doctoral Research Associate, Institut für Linguistik, Universität Leipzig, Germany RESEARCH & TEACHING INTERESTS Topic Areas Phonetics-phonology interfaces, prosodic domains, typology, language documentation, language contact & maintenance/shift, language revitalization, grammaticization, discourse-functional approaches, corpus -

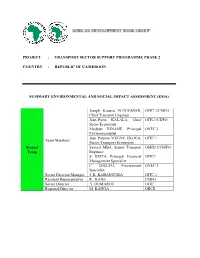

Project : Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2

PROJECT : TRANSPORT SECTOR SUPPORT PROGRAMME PHASE 2 COUNTRY : REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON SUMMARY ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Joseph Kouassi N’GUESSAN, OITC.1/CMFO Chief Transport Engineer Jean-Pierre KALALA, Chief OITC1/CDFO Socio-Economist Modeste KINANE, Principal ONEC.3 Environmentalist Jean Paterne MEGNE EKOGA, OITC.1 Team Members Senior Transport Economist Project Samuel MBA, Senior Transport OSHD.2/CMFO Team Engineer S. KEITA, Principal Financial OITC1 Management Specialist C. DJEUFO, Procurement ONEC.3 Specialist Sector Division Manager J. K. KABANGUKA OITC.1 Resident Representative R. KANE CMFO Sector Director A. OUMAROU OITC Regional Director M. KANGA ORCE SUMMARY ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Programme Name : Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2 SAP Code: P-CM-DB0-015 Country : Cameroon Department : OITC Division : OITC-1 1. INTRODUCTION This document is a summary of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of the Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2 which involves the execution of works on the Yaounde-Bafoussam-Bamenda road. The impact assessment of the project was conducted in 2012. This assessment seeks to harmonize and update the previous one conducted in 2012. According to national regulations, the Yaounde-Bafoussam-Babadjou road section rehabilitation project is one of the activities that require the conduct of a full environmental and social impact assessment. This project has been classified under Environmental Category 1 in accordance with the African Development Bank’s Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) of July 2014. This summary has been prepared in accordance with AfDB’s environmental and social impact assessment guidelines and procedures for Category 1 projects. -

Multilingual Cameroon

GOTHENBURG AFRICANA INFORMAL SERIES – NO 7 ______________________________________________________ Multilingual Cameroon Policy, Practice, Problems and Solutions by Tove Rosendal DEPARTMENT OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN LANGUAGES 2008 2 Contents List of tables ..................................................................................................................... 4 List of figures ................................................................................................................... 4 Abbreviations ................................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 9 2. Focus, methodology and earlier studies ................................................................. 11 3. Language policy in Cameroon – historical overview............................................. 13 3.1 Pre-independence period ................................................................................ 13 3.2 Post-independence period............................................................................... 13 4. The languages of Cameroon................................................................................... 14 4.1 The national languages of Cameroon - an overview ...................................... 14 4.1.1 The language families of Cameroon....................................................... 16 4.1.2 Languages of wider distribution............................................................ -

Kodrah Kristang: the Initiative to Revitalize the Kristang Language in Singapore

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 19 Documentation and Maintenance of Contact Languages from South Asia to East Asia ed. by Mário Pinharanda-Nunes & Hugo C. Cardoso, pp.35–121 http:/nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/sp19 2 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24906 Kodrah Kristang: The initiative to revitalize the Kristang language in Singapore Kevin Martens Wong National University of Singapore Abstract Kristang is the critically endangered heritage language of the Portuguese-Eurasian community in Singapore and the wider Malayan region, and is spoken by an estimated less than 100 fluent speakers in Singapore. In Singapore, especially, up to 2015, there was almost no known documentation of Kristang, and a declining awareness of its existence, even among the Portuguese-Eurasian community. However, efforts to revitalize Kristang in Singapore under the auspices of the community-based non-profit, multiracial and intergenerational Kodrah Kristang (‘Awaken, Kristang’) initiative since March 2016 appear to have successfully reinvigorated community and public interest in the language; more than 400 individuals, including heritage speakers, children and many people outside the Portuguese-Eurasian community, have joined ongoing free Kodrah Kristang classes, while another 1,400 participated in the inaugural Kristang Language Festival in May 2017, including Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister and the Portuguese Ambassador to Singapore. Unique features of the initiative include the initiative and its associated Portuguese-Eurasian community being situated in the highly urbanized setting of Singapore, a relatively low reliance on financial support, visible, if cautious positive interest from the Singapore state, a multiracial orientation and set of aims that embrace and move beyond the language’s original community of mainly Portuguese-Eurasian speakers, and, by design, a multiracial youth-led core team. -

Central Africa, 2021 Region of Africa

Quickworld Entity Report Central Africa, 2021 Region of Africa Quickworld Factoid Name : Central Africa Status : Region of Africa Land Area : 7,215,000 sq km - 2,786,000 sq mi Political Entities Sovereign Countries (19) Angola Burundi Cameroon Central African Republic Chad Congo (DR) Congo (Republic) Equatorial Guinea Gabon Libya Malawi Niger Nigeria Rwanda South Sudan Sudan Tanzania Uganda Zambia International Organizations Worldwide Organizations (3) Commonwealth of Nations La Francophonie United Nations Organization Continental Organizations (1) African Union Conflicts and Disputes Internal Conflicts and Secessions (1) Lybian Civil War Territorial Disputes (1) Sudan-South Sudan Border Disputes Languages Language Families (9) Bihari languages Central Sudanic languages Chadic languages English-based creoles and pidgins French-based creoles and pidgins Manobo languages Portuguese-based creoles and pidgins Prakrit languages Songhai languages © 2019 Quickworld Inc. Page 1 of 7 Quickworld Inc assumes no responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions in the content of this document. The information contained in this document is provided on an "as is" basis with no guarantees of completeness, accuracy, usefulness or timeliness. Quickworld Entity Report Central Africa, 2021 Region of Africa Languages (485) Abar Acoli Adhola Aghem Ajumbu Aka Aka Akoose Akum Akwa Alur Amba language Ambele Amdang Áncá Assangori Atong language Awing Baali Babango Babanki Bada Bafaw-Balong Bafia Bakaka Bakoko Bakole Bala Balo Baloi Bambili-Bambui Bamukumbit -

The Emergence of Tense in Early Bantu

The Emergence of Tense in Early Bantu Derek Nurse Memorial University of Newfoundland “One can speculate that the perfective versus imperfective distinction was, historically, the fundamental distinction in the language, and that a complex tense system is in process of being superimposed on this basic aspectual distinction … there are many signs that the tense system is still evolving.” (Parker 1991: 185, talking of the Grassfields language Mundani). 1. Introduction 1.1. Purpose Examination of a set of non-Bantu Niger-Congo languages shows that most are aspect-prominent languages, that is, they either do not encode tense —the majority case— or, as the quotation indicates, there is reason to think that some have added tense to an original aspectual base. Comparative consideration of tense-aspect categories and morphology suggests that early and Proto-Niger-Congo were aspect-prominent. In contrast, all Bantu languages today encode both aspect and tense. The conclusion therefore is that, along with but independently of a few other Niger-Congo families, Bantu innovated tense at an early point in its development. While it has been known for some time that individual aspects turn into tenses, and not vice versa, it is being proposed here is that a whole aspect- based system added tense distinctions and become a tense-aspect system. 1.2. Definitions Readers will be familiar with the concept of tense. I follow Comrie’s (1985: 9) by now well known definition of tense: “Tense is grammaticalised expression of location in time”. That is, it is an inflectional category that locates a situation (action, state, event, process) relative to some other point in time, to a deictic centre. -

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names The vernacular names listed below have been collected from the literature. Few have phonetic spellings. Spelling is not helped by the difficulties of transcribing unwritten languages into European syllables and Roman script. Some languages have several names for the same species. Further complications arise from the various dialects and corruptions within a language, and use of names borrowed from other languages. Where the people are bilingual the person recording the name may fail to check which language it comes from. For example, in northern Sahel where Arabic is the lingua franca, the recorded names, supposedly Arabic, include a number from local languages. Sometimes the same name may be used for several species. For example, kiri is the Susu name for both Adansonia digitata and Drypetes afzelii. There is nothing unusual about such complications. For example, Grigson (1955) cites 52 English synonyms for the common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) in the British Isles, and also mentions several examples of the same vernacular name applying to different species. Even Theophrastus in c. 300 BC complained that there were three plants called strykhnos, which were edible, soporific or hallucinogenic (Hort 1916). Languages and history are linked and it is hoped that understanding how lan- guages spread will lead to the discovery of the historical origins of some of the vernacular names for the baobab. The classification followed here is that of Gordon (2005) updated and edited by Blench (2005, personal communication). Alternative family names are shown in square brackets, dialects in parenthesis. Superscript Arabic numbers refer to references to the vernacular names; Roman numbers refer to further information in Section 4.