The Prevention Against Plague in Xvi Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guida Turistica Di Villanova Monteleone

Comune di Volontari per la promozione di Villanova Monteleone Villanova Monteleone SA BIDDA MIA Biddanoa Monteleone A Biddanoa A chimbighentos e sessantases metros subra su mare est bidda mia, in sos benujos de Santa Maria e de difesa montijos at tres: unu a manca, unu a dresta e unu in pes e divisa est da s'abba in mesania e una culva roca 'e pedra ‘ia l'incoronat sa fronte. E bider des da sa serra s'istesu panorama de Janna Arghentu, e totu Logudoro e Portu Conte, Corsiga e Limbara. Duas funtanas friscas d'abba jara tenet, un'in cabita, una in su coro: de su Temo una balia, una mama. Remundu Piras Questa guida turistica di Villanova Monteleone, in italiano e in sardo, è stata ideata e curata dai volontari del Servizio Civile Nazionale del gruppo “Volontari per la promozione di Villanova Monteleone”, ed è diretta, in particolare, agli alunni delle nostre scuole. I bambini seguono i genitori nella visita di una città o di un luogo senza avere, in genere, una conoscenza diretta del contesto che frequentano. Tuttavia, visitare il nostro comune può e deve diventare anche per loro un’esperienza emozionante e formativa. Occorre tenere conto che lo sguardo del bambino è diverso da quello dell’adulto, poiché egli è attento ad altri particolari, ad altre suggestioni. Alcuni spazi del nostro comune dicono forse poco a tutti noi, ma talvolta i bambini sono attratti da luoghi, dettagli e situazioni che in loro accendono la curiosità, l’interesse e le emozioni. Perché allora un adulto non potrebbe farsi prendere per mano e provare l’esperienza di essere accompagnato da un bambino nella visita del nostro comune, magari seguendo questa guida? In essa non c’è tutto, ma chi l’ha pensata e poi realizzata ha voluto descrivere la storia, la società, le tradizioni, la natura del nostro comune con un linguaggio semplice, diretto più al cuore che alla mente. -

Presentazione Di Powerpoint

REGIONE AUTÒNOMA DE SARDIGNA REGIONE AUTONOMA DELLA SARDEGNA Assessoradu de sos traballos pùblicos Assessorato dei lavori pubblici Ente acque della Sardegna 3a integrazione all’elenco di opere del Sistema Idrico Multisettoriale Regionale di competenza gestionale dell’ENAS in applicazione dell’art. 30 della L.R. 19/06 Sistema 3 – Nord Occidentale 3B Coghinas – Mannu di Portotorres Allegato 3 – Individuazione cartografica e caratteristiche tecniche delle opere Sistema 3 Nord Occidentale Schema idraulico 3B Coghinas - Mannu di Portotorres Il Direttore Generale f.f. Ing. Franco Ollargiu Aggiornamento Maggio 2014 3a integrazione all’elenco di opere del Sistema Idrico Multisettoriale Regionale di competenza gestionale dell’ENAS in applicazione dell’art. 30 della L.R. 19/06 Elenco delle opere schema idraulico 3B Coghinas-Mannu di Portotorres Codice Tipo Denominazione 3B.S1 Diga Muzzone 3B.S2 Diga Casteldoria 3B.C1 Opera di trasporto Galleria restituzione Coghinas 3B.C13 Opera di trasporto Condotta forzata centrale Coghinas 3B.C14 Opera di trasporto Condotta forzata centrale Casteldoria 3B.C15 Opera di trasporto Galleria di restituzione centrale Casteldoria 3B.I1 Centrale idroelettrica Coghinas 3B.I2 Centrale idroelettrica Casteldoria REGIONE AUTÒNOMA DE SARDIGNA 1:50.000 REGIONE AUTONOMA DELLA SARDEGNA µ Assessoradu de sos traballos pùblicos Assessorato dei lavori pubblici Ente acque della Sardegna 3B.C15 3B.I2 d#V 3B.C14 3B.S2 Casteldoria S=DIGHE T=TRAVERSE C=OPERE DI TRASPORTO V=VASCHE, PARTITORI E PRESE P=IMPIANTI DI SOLLEVAMENTO I=CENTRALI IDROELETTRICHE S - Dighe C - Opere di trasporto I - Centrali idroelettriche 3B.C1 Legenda V# )" 3B.S1 Muzzone jk 3B.I1 V d #d Opere di trasporto 3B.C13 SISTEMA 3 NORD OCCIDENTALE Schema idraulico 3B Coghinas – Mannu di Porto Torres Schema 3B Pagina 1 SISTEMA 3 – NORD OCCIDENTALE Il sistema nord Occidentale comprende i bacini dei tre corsi d’acqua principali del Coghinas, Alto Temo, Cuga , Mannu di Porto Torres. -

Catalan Alghero: Historical Perspectives from the Vantage Point of Medieval Archaeology

CHAPTER 14 Catalan Alghero: Historical Perspectives from the Vantage Point of Medieval Archaeology Marco Milanese 1 Introduction Alghero (L’Alguer) became a Catalan city after 1354, when the Crown of Aragon definitively appropriated it after a long siege led by Peter III, “the Magnanimous,” who is also referred to as Peter IV of Aragon. Along with Cagliari, Alghero was the strategic stronghold that controlled the island in the medieval and early modern era. It was for this reason that its character as a military fortress played an important role in the view of the Crown of Aragon and, particularly, that of Spain. Until 1495, Alghero retained a more noticeably Catalan character, but the expulsion of the dense community of Algherese Jews in 1492 led to a demographic and economic crisis that Ferdinand the Catholic tried to check by conceding Algherese citizenship to Sardinians. Today, Alghero survives as a Catalan-speaking enclave on Sardinian soil, a peculiarity already meticulously studied at the end of the nineteenth century by Eduard Toda i Güell.1 The historic city of Alghero was founded on a peninsula stretching out into the sea, oriented northwest, with an inlet protected from north- and south- west winds (Fig. 14.1). The old city was circumscribed within the circuit of a sixteenth-century wall (visible today only in intermittent stretches due to drastic demolition in the late nineteenth century). Since 1996, this circuit wall has been the object of numerous planned, preventative, and rescue ar- chaeological interventions conducted cooperatively by the Amministrazione Comunale of Alghero, the archaeological Soprintendenza of Sassari and Nuoro, and the Department of History of the University of Sassari (Fig. -

Sassari Li Punti Alghero Bonorva Ozieri Olbia Tempio

Via Piandanna,10/E – 07100 Sassari Tel. + 39 079 3769100 – Fax + 39 079 3769200 COMUNICATO STAMPA Sassari e Provincia Da Equitalia Sardegna 9 punti di riscossione per pagare la prima rata Ici Equitalia Sardegna informa i contribuenti che, in occasione della scadenza della prima rata dell’Ici per l’anno 2009, che deve essere pagata entro il 16 giugno, sono a disposizione casse veloci e sportelli ad hoc presso comuni e circoscrizioni. Si ricorda che, in base al decreto legge 27 maggio 2008 n. 93, l’imposta non deve essere versata né per la casa dove il contribuente dimora abitualmente, né per i fabbricati considerati come pertinenze (per esempio, garage, cantine e box) dai regolamenti locali anche se sono iscritte distintamente nel catasto, né, infine, per gli altri immobili che il comune ha assimilato all’abitazione principale. L’Ici si continua a pagare, invece, sulle abitazioni principali che rientrano nelle categorie catastali A1 (abitazioni di tipo signorile), A8 (abitazioni in ville) e A9 (castelli e palazzi di pregio), oltrechè sulle case che non costituiscono abitazione principale. Di seguito, orari e indirizzi per provvedere al pagamento: giorni di apertura orari SASSARI Equitalia Sardegna: Via Piandanna, 10/e TUTTI I GIORNI dal lunedì al venerdì 8.20/13.00 c/o Ufficio Tributi del Comune: Via Wagner giorni 9,10,11,12,15 e16 giugno 8.30/13.00 LI PUNTI c/o locali Circoscrizione giorni 9,10,11,12,15 e16 giugno 8.30/13.00 ALGHERO Sportello Equitalia: Via Don Minzoni, 41 TUTTI I GIORNI dal lunedì al venerdì 8.20/13.00 BONORVA Sportello -

Another Case of Language Death? the Intergenerational Transmission Of

Another case of language death? The intergenerational transmission of Catalan in Alghero Enrico Chessa Thesis submitted for the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Queen Mary, University of London 2011 1 The work presented in this thesis is the candidate’s own. 2 for Fregenet 3 Table of Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................................... 8 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 9 Abbreviations ......................................................................................................................... 11 List of Figures ........................................................................................................................ 12 List of Tables ......................................................................................................................... 15 Chapter 1: Introduction .......................................................................................................... 17 1.1 Scope of the thesis ........................................................................................................... 17 1.1.1 Preliminary remarks .................................................................................................. 17 1.1.2 This study and the language shift paradigm .............................................................. 25 1.1.3 An ethnography of language shift ............................................................................ -

Sardinia and Corsica 1 Pages

Sardinia Regional Discovery | 8 Days HIGHLIGHTS AND INCLUSIONS DAY 1 Cagliari at Tuerredda beach where you will have time DAY 6 Alghero – Castelsardo – Costa for an independent lunch at their famous Smeralda (B) beachfront restaurant and time to swim before > 7 nights in 4 and 5 star hotels. Welcome to Cagliari, Sardinia’s capital. Cagliari, heading back to Cagliari. > Guided walking tour of Cagliari located on the Bay of Angels, is an ancient Depart for Costa Smeralda with a stop in fortified city that has seen the rule of civilisations perched over the Bay of Angels. Castelsardo, considered one of the for over 5000 years. Transfer to your hotel and DAY 4 Cagliari – S Naraxi di Barumini – most beautiful villages in Italy. > Excursion to the ancient town and enjoy an evening at leisure. Alghero (B, L) RECOMMENDED HOTELS: 5 star – Cervo Hotel archaeological ruins of Nora. RECOMMENDED HOTELS: 4 star – Hotel Villa Costa Smeralda. > Guided tour of the UNESCO World Fanny. 3 star – Palazzo Dessy Guesthouse. Enjoy a scheduled guided tour of the UNESCO Heritage Listed Su Naraxi di World Heritage Listed Su Naraxi di Barumini. DAY 7 Costa Smeralda – Maddalena Barumini. DAY 2 Cagliari (B) The defensive structures date to 2000BC and Archipelago - Costa Smeralda (B) > Visit charming Sardinian towns of consist of circular towers of truncated cones Alghero and Castelsardo. Enjoy a half day morning walking tour of the built of stone. Continue to one of Sardinia’s Enjoy a full day excursion by boat from Palau > Wine tasting at a local Sardinian historic medieval Castello with its ancient most renounced wineries for a cellar tour, to the Maddalena Archipelago consisting winery with light lunch (L) fortifications, 14th century towers and town hall. -

Anno Scolastico 2018-19 SARDEGNA AMBITO 0001

Anno Scolastico 2018-19 SARDEGNA AMBITO 0001 - SASSARI-ALGHERO Elenco Scuole I Grado Ordinato sulla base della prossimità tra le sedi definita dall’ufficio territoriale competente SEDE DI ORGANICO ESPRIMIBILE DAL Altri Plessi Denominazione altri Indirizzo altri Comune altri PERSONALE Scuole stesso plessi-scuole stesso plessi-scuole stesso plessi-scuole Codice Istituto Denominazione Istituto DOCENTE Denominazione Sede Caratteristica Indirizzo Sede Comune Sede Istituto Istituto Istituto stesso Istituto SSIC800001 PERFUGAS " S. SATTA-A. SSMM800012 PERFUGAS - NORMALE VIA LA MARMORA PERFUGAS SSMM800023 S.M. CHIARAMONTI VIA DELLA RESISTENZA CHIARAMONTI FAIS" "SEBASTIANO SATTA" SSMM800034 PLOAGHE - S.M. "A. FAIS" VIA PIETRO SALIS PLOAGHE SSIC81100B ELEONORA SSMM81101C CASTELSARDO NORMALE VIA COLOMBO CASTELSARD SSMM81102D S.M. SEDINI VIA S. GIACOMO SEDINI D'ARBOREA-CASTELSAR -ELEONORA D'ARBOREA O DO SSIC82800R OSILO SSMM82801T OSILO - SCUOLA MEDIA NORMALE VIA BRIGATA SASSARI, OSILO SSMM82802V S.M. NULVI VIA SASSARI 1 NULVI 1 SSIC855005 ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO SSMM855016 SCUOLA MEDIA VIA NORMALE VIA MONTE GRAPPA SASSARI "P.TOLA" MONTE GRAPPA SSIC856001 ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO SSMM856012 SCUOLA MEDIA VIA NORMALE VIA MASTINO, 6 SASSARI BRIGATA SA MASTINO SSIC839007 SALVATORE FARINA SSMM839018 SCUOLA MEDIA NORMALE CORSO FRANCESCO SASSARI "SALVATORE FARINA" COSSIGA N? 6 SSIC85700R ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO SSMM85701T SCUOLA MEDIA VIA NORMALE VIA GORIZIA SASSARI PERTINI - GORIZIA SSMM097008 C.P.I.A. N. 5 SASSARI SSCT70000T ANTONIO GRAMSCI ADULTI VIA UGO LA MALFA, -

Posti Disponibili Dopo I Movimenti Rettifiche 10 7 2020-Signed

PROSPETTO ORGANICO E TITOLARI PERSONALE ATA ANNO SCOLASTICO: 2020/21 DATA: 10/07/2020 – RETTIFICATI UFFICIO SCOLASTICO PROVINCIALE DI: SASSARI NUMERO CODICE DENOMINAZIONE DENOMINAZION DENOMINAZIONE NUMERO POSTI PERDENTI POSTI PROFILO CODICE AREA TIPO SCUOLA TITOLARI SU DISPONIBILITA' SCUOLA SCUOLA E AREA COMUNE IN ORGANICO POSTO ACCANTONATI SCUOLA SSCT70000T ANTONIO GRAMSCI ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE SASSARI 1 1 0 0 SASSARI SSCT70000T ANTONIO GRAMSCI COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE SASSARI 1 1 0 0 SASSARI SSCT70100N SEBASTIANO ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE ALGHERO 1 0 1 0 SATTA ALGHERO SSCT70100N SEBASTIANO COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE ALGHERO 1 1 0 0 SATTA ALGHERO SSCT70200D A.DIAZ OLBIA ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE OLBIA 1 1 0 0 SSCT70200D A.DIAZ OLBIA COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE OLBIA 1 0 1 0 SSCT703009 GRAZIA DELEDDA ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE OZIERI 1 0 1 0 OZIERI SSCT703009 GRAZIA DELEDDA COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE OZIERI 1 1 0 0 OZIERI SSCT704005 CTP ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE CASTELSARDO 0 0 0 0 CASTELSARDO SSCT704005 CTP COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE CASTELSARDO 0 0 0 0 CASTELSARDO SSCT705001 CTP BERCHIDDA ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE OSCHIRI 0 0 0 0 SSCT705001 CTP BERCHIDDA COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE OSCHIRI 0 0 0 0 SSCT70600R CTP VALLEDORIA ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE BADESI 1 1 0 0 SSCT70600R CTP VALLEDORIA COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE BADESI 1 1 0 0 SSCT70700L CTP SANTA ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE SANTA TERESA 1 0 1 0 TERESA GALLURA GALLURA SSCT70700L -

Rally Italia Sardegna 2019

RALLY ITALIA SARDEGNA 2019 Date: 6 June 2019 Time: 12:00 Subject: Bulletin 3 Document: 1.3 (page 1) From: The Clerk of the course To: All competitors - Crew members Number of pages: 3 Attachments: 10: 1 - List of compulsory attendees to Drivers’ Safety Briefing 2 - Itinerary Rally HQ - Chiostro San Francesco (NO CARS) 3 - TOTAL Refuel Schedule 4 - Recce Ittiri Layout 5 - New Layout page 59 of Road book 1(MEDIA ZONE) 6 - RB of itinerary from GRASCIOLEDDU-Shakedown Start to ALGHERO-Service IN 7 - RB of itinerary of Sector between TC8 and TC9 8 - Latest version of the Itinerary (vers. Bull3-06.06.2019) 9 - Latest version of the Reconnaissance Schedule 10 - Clarification of Article 40.3 of the 2019 FIA WRC Sporting Regulations A) Supplementary Regulations 1. Introduction 1.3 Overall SS distance and total route distance (update) - Total route: 1.383,64 1.377,58 km B) Supplementary Regulations 2. Organisation (update) 2.5 FIA Delegates - Sporting Delegate: Mr. Andrew WHEATLEY • Assistant to the Technical Delegate (new): Mr. Francesco UGUZZONI 2.7 Rally HQ Alghero - Race control contacts - Phone: +39 079 9576848 C) Supplementary Regulations 3. Programme (update) 3.2 Schedule during the rally week Wednesday 12 June 18:00 - 18:15 Autograph’s session 19:00 Safety Briefing for drivers and co-drivers summoned by the CoC (Attachments 1 and 2) Rally HQ Chiostro San Francesco Thursday 13 June 12:00 13:00 “Meet the Crew” Rally SP - ACI Stage WRC Stage 13:30 “Photo shoot” (selected drivers) WRC Stage 13:00 13:45 Pre-event FIA Press Conference Rally HQ -

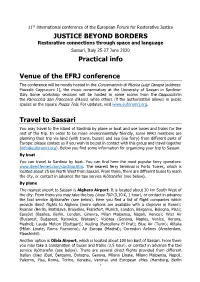

JUSTICE BEYOND BORDERS Restorative Connections Through Space and Language Sassari, Italy 25-27 June 2020 Practical Info

11th international conference of the European Forum for Restorative Justice JUSTICE BEYOND BORDERS Restorative connections through space and language Sassari, Italy 25-27 June 2020 Practical info Venue of the EFRJ conference The conference will be mostly hosted in the Conservatorio di Musica Luigi Canepa (address: Piazzale Cappuccini 1), the music conservatory at the University of Sassari in Sardinia- Italy. Some workshop sessions will be hosted in some rooms from the Cappuccini in the Parrocchia San Francesco d’Assisi, while others (if the authorization allows) in public spaces as the square Piazza Tola. For updates, visit www.euforumrj.org. Travel to Sassari You may travel to the island of Sardinia by plane or boat and use buses and trains for the rest of the trip. In order to be more environmentally friendly, some EFRJ members are planning their trip via land (with trains, buses) and sea (via ferry) from different parts of Europe: please contact us if you wish to be put in contact with this group and travel together ([email protected]). Below you find some information for organizing your trip to Sassari. By boat You can travel to Sardinia by boat. You can find here the most popular ferry operators: www.directferries.com/sardinia.htm. The nearest ferry terminal is Porto Torres, which is located about 25 km North West from Sassari. From there, there are different buses to reach the city, or contact in advance the taxi service Ajòtransfer (see below). By plane The nearest airport to Sassari is Alghero Airport. It is located about 30 km South West of the city. -

Hydrogeology of the Nurra Region, Sardinia (Italy): Basement-Cover Influences on Groundwater Occurrence and Hydrogeochemistry

Hydrogeology of the Nurra Region, Sardinia (Italy): basement-cover influences on groundwater occurrence and hydrogeochemistry Giorgio Ghiglieri & Giacomo Oggiano & Maria Dolores Fidelibus & Tamiru Alemayehu & Giulio Barbieri & Antonio Vernier Abstract The Nurra district in the Island of Sardinia lows are generated by synclines and normal faults. The (Italy) has a Palaeozoic basement and covers, consisting regional groundwater flow has been defined. The investi- of Mesozoic carbonates, Cenozoic pyroclastic rocks and gated groundwater shows relatively high TDS and Quaternary, mainly clastic, sediments. The faulting and chloride concentrations which, along with other hydro- folding affecting the covers predominantly control the geochemical evidence, rules out sea-water intrusion as the geomorphology. The morphology of the southern part is cause of high salinity. The high chloride and sulphate controlled by the Tertiary volcanic activity that generated concentrations can be related to deep hydrothermal a stack of pyroclastic flows. Geological structures and circuits and to Triassic evaporites, respectively. The lithology exert the main control on recharge and ground- source water chemistry has been modified by various water circulation, as well as its availability and quality. geochemical processes due to the groundwater–rock The watershed divides do not fit the groundwater divide; interaction, including ion exchange with hydrothermal the latter is conditioned by open folds and by faults. The minerals and clays, incongruent solution of dolomite, and Mesozoic folded carbonate sequences contain appreciable sulphate reduction. amounts of groundwater, particularly where structural Keywords Groundwater flow . Hydrogeochemistry . Salinization . Groundwater management . Italy Received: 31 March 2006 /Accepted: 15 September 2008 Introduction © Springer-Verlag 2008 The Nurra district is located in the northwestern part of the island of Sardinia (Italy) in the Sassari Province, with G. -

Ata Disponibilita Dopo I Movimenti-Signed

PROSPETTO ORGANICO E TITOLARI PERSONALE ATA ANNO SCOLASTICO: 2021/22 DATA: 25/06/2021 UFFICIO SCOLASTICO PROVINCIALE DI: SASSARI CODICE SCUOLA DENOMINAZIONE PROFILO CODICE AREA DENOMINAZIONE TIPO SCUOLA DENOMINAZIONE NUMERO POSTI NUMERO DISPONIBILITA' SSCT70000T ANTONIO ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE SASSARI 1 1 0 SSCT70000T ANTONIO COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE SASSARI 1 1 0 SSCT70100N SEBASTIANO ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE ALGHERO 1 0 1 SSCT70100N SEBASTIANO COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE ALGHERO 1 1 0 SSCT70200D A.DIAZ OLBIA ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE OLBIA 1 0 1 SSCT70200D A.DIAZ OLBIA COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE OLBIA 1 0 1 SSCT703009 GRAZIA DELEDDA ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE OZIERI 1 0 1 SSCT703009 GRAZIA DELEDDA COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE OZIERI 1 1 0 SSCT704005 CTP ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE CASTELSARDO 0 0 0 SSCT704005 CTP COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE CASTELSARDO 0 0 0 SSCT705001 CTP BERCHIDDA ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE OSCHIRI 0 0 0 SSCT705001 CTP BERCHIDDA COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE OSCHIRI 0 0 0 SSCT70600R CTP VALLEDORIA ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE BADESI 1 1 0 SSCT70600R CTP VALLEDORIA COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE BADESI 1 1 0 SSCT70700L CTP SANTA ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE SANTA TERESA 1 0 1 SSCT70700L CTP SANTA COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE SANTA TERESA 1 0 1 SSEE02500B I CIRCOLO - ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO NORMALE OLBIA 6 6 0 SSEE02500B I CIRCOLO - COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO NORMALE OLBIA 0 0 0 OLBIA TECNICO (ADDETTO AZIENDE SSEE02500B I CIRCOLO