The Emergence of Modern Hinduism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compassion for Living Creatures in Indian Law Courts

religions Article Compassion for Living Creatures in Indian Law Courts Gilles Tarabout Director of Research (Emeritus), National Centre for Scientific Research, 75016 Paris, France; [email protected] Received: 27 March 2019; Accepted: 10 June 2019; Published: 14 June 2019 Abstract: The Constitution of India through an amendment of 1976 prescribes a Fundamental Duty ‘to have compassion for living creatures’. The use of this notion in actual legal practice, gathered from various judgments, provides a glimpse of the current debates in India that address the relationships between humans and animals. Judgments explicitly mentioning ‘compassion’ cover diverse issues, concerning stray dogs, trespassing cattle, birds in cages, bull races, cart-horses, animal sacrifice, etc. They often juxtapose a discourse on compassion as an emotional and moral attitude, and a discourse about legal rights, essentially the right not to suffer unnecessary pain at the hands of humans (according to formulae that bear the imprint of British utilitarianism). In these judgments, various religious founding figures such as the Buddha, Mahavira, etc., are paid due tribute, perhaps not so much in reference to their religion, but rather as historical icons—on the same footing as Mahatma Gandhi—of an idealized intrinsic Indian compassion. Keywords: India; animal welfare; compassion; Buddhism; court cases In 1976, the 42nd Amendment to the Constitution of India introduced a new section detailing various Fundamental Duties1 that citizens were to observe. One of these duties is ‘to protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers and wild life, and to have compassion for living creatures’ (Constitution of India, Part IV-A, Art. -

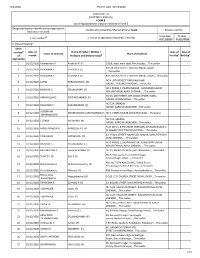

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applica Ons For

12/2/2020 Form9_AC6_02/12/2020 ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where applicaons Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Avadi Revision identy have been received) From date To date @ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 1. List number 01/12/2020 01/12/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial $ Date of Name of Father / Mother / Date of Time of number Name of claimant Place of residence of receipt Husband and (Relaonship)# hearing* hearing* applicaon 1 01/12/2020 Manikandan K Krishnan R (F) 135/8, avadi main road, Paruthipau, , Thiruvallur #20, BOUND STREET, KOVILPATHAGAI, AVADI 2 01/12/2020 PRASANNA E ELANGO R (F) , , Thiruvallur 3 01/12/2020 PRASANNA E ELANGO R (F) #20, BOUND STREET, KOVILPATHAGAI, AVADI, , Thiruvallur NO 6 , 8TH STREET THIRUVALLUVAR 4 01/12/2020 LATHA PARAMASIVAM (H) NAGAR, THIRUMULLAIVOYAL, , Thiruvallur NO 5 PHASE 1, SWATHI NAGAR , KANNADAPALAYAM 5 01/12/2020 BHAVANI S SELVAKUMAR (F) KOVILPATHAGAI AVADI CHENNAI , , Thiruvallur NO 26, 2ND STREET, 4TH CROSS STREET, INDRA 6 01/12/2020 AMANULLAH S SYED MOHAMED (F) NAGAR, CHOLAPURAM, , Thiruvallur NO 72A, SARADHI 7 01/12/2020 RAJAMANI C EAKAMBARAM (F) NAGAR, KARUNAKARACHERI, , Thiruvallur SUBISHANA 8 01/12/2020 DHARMAGURU LAKSHMANAN (F) NO 1, INDRA NAGAR, KOVILPADHAGAI, , Thiruvallur DHARMAGURU NO 72A, SARATHI 9 01/12/2020 C GIRIJA RAJAMANI (H) NAGAR, KARUNAKARACHERI, , Thiruvallur PLOT NO 91, 6 TH STREET THIRUMALAI VASAN NAGAR S 10 01/12/2020 MANU RAMESH R RAMESAN P G (F) M NAGAR POST, -

INDIAN LITERATURE Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D

INDIAN LITERATURE Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D. Study Guide Description This course covers the literature of south Asia, from early Vedic Ages, and through classical time, and the rise of various empires. It also explores the rise of different religions and convergences of them, and then the transition from colonial control to independence. Students will analyze primary texts covering the genres of poetry, drama, fiction and non-fiction, and will discuss them from different critical stances. They will demonstrate their knowledge and understanding of the works by responding to questions focusing on the works, movements, authors, themes, and motifs. In addition, they will discuss the historical, social, cultural, or biographical contexts of the works‘ production. This course is intended for students who already possess a bachelor‘s and, ideally, a master‘s degree, and who would like to develop interdisciplinary perspectives that integrate with their prior knowledge and experience. About the Professor This course was prepared by Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D., research associate / research fellow, University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, Department of Languages and Cultures of South Asia. Contents Pre-classical Classical Early Post –classical Late Post-classical Early Modern 19th Century Early 20th Century Late 20th Century © 2017 by Humanities Institute PRE-CLASSICAL PERIOD POETRY Overview Pre-classical Indian literature contains two types of writing: poetry and commentary (which resembles the essay). These ancient texts (dating from about 1200 to 400 BCE) were composed, transmitted and recited in Sanskrit by Brahmin priests. It is poetry, however, that dominates the corpus of Vedic literature and is considered the more sacred style of expression. -

The Emergence of Modern Hinduism

1 Introduction Rethinking Religious Change in Nineteenth-Century South Asia For millennia, one of the most consistent characteristics of Hindu traditions has been variation. Scholarly work on contemporary Hinduism and its premodern antecedents ably captures this complexity, paying attention to a wide spectrum of ideologies, practices, and positions of authority. Studies of religion in ancient India stress doctrinal variation in the period, when ideas about personhood, liberation, the efficacy of ritual, and deities were all contested in a variety of texts and con- texts. Scholarship on contemporary Hinduism grapples with a vast array of rituals, styles of leadership, institutions, cultural settings, and social formations. However, when one turns to the crucial period of the nineteenth century, this complexity fades, with scholars overwhelmingly focusing their attention on leaders and move- ments that can be considered under the rubric “reform Hinduism.” The result has been an attenuated nineteenth-century historiography of Hinduism and a unilin- eal account of the emergence of modern Hinduism. Narratives about the emergence of modern Hinduism in the nineteenth century are consistent in their presumptions, form, and content. Important aspects of these narratives are familiar to students who have read introductory texts on Hinduism, and to scholars who write and teach those texts. At the risk of present- ing a caricature of these narratives, here are their most basic characteristics. The historical backdrop includes discussions of colonialism, Christian missions, and long- standing Hindu traditions. The cast of characters is largely the same in every account, beginning with Rammohan Roy and the Brahmo Samaj, moving on to Dayananda Saraswati and the Arya Samaj, and ending with Swami Vivekananda’s “muscular” Hinduism. -

A Novel Approach to Harness Maximum Power from Solar PV Panel 10-16 G

EDITORIAL Dear Members, Fellow Professionals, Friends and Well wishers, The Profession of ‘Electrical Installation Engineer’ revolves around Technology, Efficiency and Safety. Safety and Reliability are of utmost Concern with equal concern for Technology and Efficiency as they direct us to Better Controls and Conservation. 11th of May is marked as “National Technology Day” and let us remember that the Technological Inventions and Improvements have, in fact, been the cause for all our Galloping Developments over the past 150 years, but ;Challenges’ continue to remain. One of the important challenges is the “Storage of Electricity” and the solutions available at present are Storage Batteries of Lead Acid and other types with their limitations of capacities and weights and Life etc. Continuous researches are taking place all over the World and even as recently as April ’13, some land mark successes have been achieved. Announcement of successful design of low-cost, long-life battery that could enable solar and wind energy to become major suppliers to the electrical grid has come as a step forward. Currently the electrical grid cannot tolerate large and sudden power fluctuations caused by wide swings in sunlight and wind. As solar and wind’s combined contributions to an electrical grid approach 20 percent, energy storage systems must be available to smooth out the peaks and valleys of this “intermittent” power — storing excess energy and discharging when input drops. For solar and wind power to be used in a significant way, we need a battery made of economical materials that are easy to scale and still efficient, and it is believed that the new battery may be the best yet designed to regulate the natural fluctuations of these alternative energies. -

Athisarapitham

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF SIDDHA Chennai – 47 THE TAMIL NADU DR. M.G.R. MEDICAL UNIVERSITY, CHENNAI - 32 A STUDY ON ATHISARAPITHAM (DISSERTATION SUBJECT) For the partial fulfillment of the requirements to the Degree of DOCTOR OF MEDICINE (SIDDHA) BRANCH V – NOI NAADAL DEPARTMENT SEPTEMBER – 2008 Chapter Contents Page no. No. Acknowledgement I Introduction 1 1.1.Sukarana Nilai in Siddha System 3 1.2.Kukarana Nilai in Siddha System 41 1.3.Diagnostic Methodology 47 II Aim and Objectives 62 64 III Review of Literature - Siddha 1. Yugi Vaithiya Chinthamani 65 2. Survey of other Siddha literature 66 IV Pathological View of Dissertation Topic 79 V Review of Modern Literature 101 VI Evaluation of Dissertation Topic 117 6.1. Materials and Methods 120 6.2. Observations and Results 6.3. Allied parameters VII Discussion 137 VIII Summary and Conclusion 145 Annexure Bibliography 2 AACCKKNNOOWWLLEEDDGGEEMMEENNTT 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I express my sincere thanks to our Vice-chancellor, The Tamil Nadu Dr. M. G. R. Medical University, Chennai. I take this opportunity to express my gratitude and acknowledgement to Dr. S. Boopathi Raj, M.D. (S)., Director, National Institute of Siddha, Chennai – 47 for giving me permission to utilize the facilities available in the college to complete my dissertation work. I express my sincere thanks to Prof. Dr. Manickavasagam, M.D. (S). Dean, National Institute of Siddha, Chennai. I express my deep sense of gratitude, debtfulness, dignity and diligent salutations to Prof. Dr. M. Logamanian, M.D. (S)., Ph .D, Head of the Department, Noi Naadal Hospital Superindent, National Institute of Siddha, Chennai. -

1 Tamil Siddhar Jeeva Samadhi Prepared by Arockia

jkpo; rpj;jHfs; [Pt rkhjp ,lq;fs; Tamil Siddhar’s Jeeva Samadhi Places in Tamil Nadu , Andrapradesh and Kerala 1. Andhra Narayanavanam Sorakaya Swami Sorakaya Swami Samadhi, Pradesh Narayanavanam, 3 Kms from Puthur, 35 km away from Tirupati 2. Andhra Mantralayam Guru Raghavendrar 13 Kms from Mantralayam Road Pradesh Swamy Railway Station near the banks of Adhoni River 3. Arakkonam Sirunamalli Arunchalaya Ayya Sirunamalli near (Nemili) 4. Arakkonam Naagavedu Amalananda Swamigal Amalananda Swamigal Madam, Vimalananda Swamigal Naagavedu (near Arakkonam) 5. Arakkonam Narasingapuram Arulananda Swamigal Arulananda Swamigal Madalayam, Narasingapuram-from Arakkonam via Kavanur 6. Aruppukottai Aruppukottai Veerabadhra Swamy Near Pavadi Thoppu (Ayya Swamy) 7. Aruppukottai Aruppukottai Dakshinamoorty Swamy Near Sokkalingapuram Nehru Park 8. Aruppukottai Aruppukottai Suppan Swamiyar Near Kamatchi Amman Temple in Sokkalingapuram 9. Aruppukottai Aruppukottai Athmananda Rama Near Sokkalingapuram Sivan Swamy Temple Pond - West side 10. Aruppukottai Mettu Gundu Kadaparai Azhagar Sami Mettu Gundu Thatha 11. Aruppukottai Mettu Gundu Thakaram Thatti Thatha At Mettu Gundu - enroute Aruppukottai-Irukkankudi 12. Aruppukottai Puliyooran Village Puliyooran Siddhar 10 Kms from Aruppukottai at Puliyooran Village 13. Aruppukottai Kattangudi Reddi Swamy 15 Kms from Aruppukottai at Kattangudi 14. Aruppukottai Kottur Kottur Guru Swamy Kottur Village 15. Aruppukottai Vembur Kandavel Paradesi 20 Kms-Enroute Aruppukottai- Ettayapuram at Vembur 16. Aruppukottai Vadakku Natham Arumugha Swamy Vadakku Natham Village 17. Chennai Kalpakkam Sadguru Om Sri Siddhar Puthupattinam near Kalpakkam Swamy 18. Chennai Ambattur Kanniyappa Swami Ambathur State Bank Colony 19. Chennai Vadapalani Annasami, Rathinasami, Valli Thirumana Mantapam, Bakiyaligam Nerkundram Road, Vadapalani, Chennai - 600026 Ph No: 24836903 20. Chennai Rajakilpakkam Sachidananda Sadguru Akanda Paripoorna Sachidananda Swami Sabha, Rajakilpakkam (Between East Tamparam-Velachery) 21. -

Universalism, Dissent, and Canon in Tamil Śaivism, Ca. 1675-1994

BEYOND THE WARRING SECTS: UNIVERSALISM, DISSENT, AND CANON IN TAMIL ŚAIVISM, CA. 1675-1994 by Eric Steinschneider A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department for the Study of Religion University of Toronto © Copyright by Eric Steinscheider 2016 Beyond the Warring Sects: Universalism, Dissent, and Canon in Tamil Śaivism, ca. 1675-1994 Eric Steinschneider Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department for the Study of Religion University of Toronto 2016 Abstract Scholarship on the formation of modern Hindu universalism in colonial South Asia has tended to focus on the Western-gazing and nationalist discourses of acculturated elites. Less attention, however, has been paid to comparable developments within the regionally situated vernacular religious traditions. The present dissertation addresses this issue by considering how several distinctly vernacular Śaiva traditions in Tamil-speaking Southern India transformed through the impact of the colonial encounter. At the center of this transformation, which produced “Tamil Śaivism” as a monolithic Tamil religion, was a shift in the way in which these sectarian traditions articulated and contested specific interpretations of Śaiva theology and sacred textuality. Chapter One contextualizes the thesis’ arguments by focusing on the internally diverse character of early-modern Tamil Śaiva intellectual culture, and more especially on the phenomenon of pan-sectarianism in two contemporary eclectic Tamil Vīraśaiva treatises. The next three chapters explore how such pan-sectarian claims were placed under enormous pressure in the nineteenth century. Chapter Two examines a low-caste commentary on a classic of Tamil Advaita Vedānta that attempts to critique the orthodox religious establishment and reinscribe Śaivism as a monism. -

Beyond Words

Beyond Words Other Books by Sri Swami Satchidananda Enlightening Tales Integral Yoga Hatha The Golden Present Kailash Journal Bound To Be Free: The Liberating The Living Gita Power of Prison Yoga To Know Your Self The Healthy Vegetarian Yoga Sutras of Patanjali Heaven on Earth How to Find Happiness Meditation Gems of Wisdom The Key to Peace Pathways to Peace Overcoming Obstacles Satchidananda Sutras Adversity and Awakening Books About Sri Swami Satchidananda Boundless Giving Sri Swami Satchidananda: Apostle of Peace Sri Swami Satchidananda: Portrait of a Modern Sage The Master’s Touch Other Titles from Integral Yoga Publications Dictionary of Sanskrit Names Everybody’s Vegan Cookbook Hatha Yoga for Kids—By Kids Imagine That—A Child’s Guide to Yoga Inside the Yoga Sutras Lotus Prayer Book Meditating with Children Sparkling Together LOTUS: Light Of Truth Universal Shrine Beyond Words Sri Swami Satchidananda Edited by Lester Alexander Designed by Victor Zurbel with the drawings of Peter Max Integral Yoga® Publications, Yogaville®, Buckingham, Virginia Library of Congress Cataloging in Publications Data Satchidananda, Swami Beyond Words 1. Spiritual life (Hinduism)—Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Conduct of life—Addresses, essays, lectures. I.Title. BL1228.S27 294.5’44 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 76-29896 ISBN 978-0-932040-37-4 Integral Yoga® Publications edition: 1992 Second Integral Yoga® Publications Printing: 1999 Third Integral Yoga® Publications Printing: 2008 The Integral Yoga® Publications edition is the fourth publication of Beyond Words. Copyright © 1977 by Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville® Drawings copyright ©1977 by Peter Max All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form. -

The Modernity of Yoga Powers in Colonial India

6 The Modernity of Yoga Powers in Colonial India If Ramalinga’s 1867 verses emphasized his place in a lineage of Shaiva bhakti poet- saints, poems published after his death led his followers and others to include him among the antinomian Tamil siddhas. The publication of the sixthTirumu ṟai in 1885, more than a decade after his death, was to significantly reconfigure his lit- erary corpus and his Shaiva legacy. These verses were explicitly critical of cor- nerstones of established Shaivism, such as ritual practices, caste hierarchies, and textual elitism. The critical spirit of these poems, along with Ramalinga’s claim to wield supernatural powers, contributed to his reputation as siddha, a poet who juxtaposed social critiques with miraculous claims. In these poems, Ramalinga was not seeking Shaiva respectability and, indeed, many aspects of their message is hardly recognizable as Shaiva. In this chapter I focus on these poems, and on this Ramalinga—Ramalinga the siddha. It is as siddha that Ramalinga’s status as a modern religious leader seems to be most ambiguous. In the poems of the sixth Tirumuṟai, Ramalinga ridicules the Vedas and Agamas; calls for the abolishing of caste; and promotes a commu- nity that is open to all, regardless of caste or class. He also speaks openly of his acquisition of supernatural powers, and he promises these powers and eternal life to anyone who joins him. If his egalitarianism appears to align with dominant conceptions of modernity, his promotion of the miraculous is contrary to those rationalizing processes that are central to those dominant conceptions. -

SAI | Newsletter

NEWSLETTER www.sai.uni-heidelberg.de No. 5, July 2014 WELCOME to this fifth edition of theSAI | Newsletter. The summer term was marked by the farewell of two eminent researchers and professors who have CONTENT contributed to the prospering academic life of the SAI in manifold and significant ways: After five years Prof. Wiqar Ali Shah has completed NEWS his last stint of the Allama Iqbal Professorial Fellowship and after more TEACHING than twenty years as head of the Department of Political Science at SAI Prof. Subrata Mitra set off for retirement. Both colleagues will be deeply RESEARCH missed at the institute and though replacements are on the way and PEOPLE will hopefully be arriving at Heidelberg in the next year, it seems hard to imagine that they will be adequately replaced. For the time being it’s BOOKS & time to say goodbye and thus farewell receptions were organized for PUBLICATIONS Prof. Ali Shah and Prof. Mitra on which occasion colleagues, friends, CONTACT family and students gathered in big numbers. Read more about it inside this newsletter. A number of new developments are to be reported and you will find more details when flipping through the following pages. Among these are the founding of the Sri Lanka Working Group that has initiated a Sri Lanka lecture series in the summer term. Together with the opening of the branch office in Colombo, for which local branch office manager Darshi Thoradeniya was employed in early 2014, we have all the good reasons to believe that research on this part of South Asia will flour- ish. -

UNIT-V I)Rajaram Mohan Rai

UNIT-V I)Rajaram Mohan Rai: Ram Mohan Roy, Ram Mohan also spelled Rammohun, Rammohan, or Ram Mohun, (born May 22, 1772, Radhanagar, Bengal, India—died September 27, 1833, Bristol, Gloucestershire, England), Indian religious, social, and educational reformer who challenged traditional Hindu culture and indicated lines of progress for Indian society under British rule. He is sometimes called the father of modern India. Early Life He was born in British-ruled Bengal to a prosperous family of the Brahman class (varna). Little is known of his early life and education, but he seems to have developed unorthodox religious ideas at an early age. As a youth, he traveled widely outside Bengal and mastered several languages—Sanskrit, Persian, Arabic, and English, in addition to his native Bengali and Hindi. Roy supported himself by moneylending, managing his small estates, and speculating in British East India Company bonds. In 1805 he was employed by John Digby, a lower company official who introduced him to Western culture and literature. For the next 10 years Roy drifted in and out of British East India Company service as Digby’s assistant. Roy continued his religious studies throughout that period. In 1803 he composed a tract denouncing what he regarded as India’s superstition and its religious divisions, both within Hinduism and between Hinduism and other religions. As a remedy for those ills, he advocated a monotheistic Hinduism in which reason guides the adherent to “the Absolute Originator who is the first principle of all religions.” He sought a philosophical basis for his religious beliefs in the Vedas (the sacred scriptures of Hinduism) and the Upanishads (speculative philosophical texts), translating those ancient Sanskrit treatises into Bengali, Hindi, and English and writing summaries and treatises on them.