Compassion for Living Creatures in Indian Law Courts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year in Review

2012YEAR IN REVIEW THANK YOU Dear Friends, grassroots outreach events, humane education workshops, and compelling advertising 2012 was truly a groundbreaking year at campaigns, MFA is inspiring a new Mercy For Animals. In the last 12 months generation to explore a vegan lifestyle. we have opened the hearts and minds of tens of millions of Americans to the plight of Our efforts are having an impact—exposing animals who suffer behind the closed doors of cruelty and motivating change. As public our nation’s factory farms, livestock auctions, awareness continues to grow regarding and slaughterhouses. Our undercover factory farming, the demand for meat is finally investigations have cast a bright light on on the decline, meaning that hundreds of abusive practices, and our legal advocacy millions of animals will be spared the horrors efforts have led to arrests, prosecutions, and of industrial animal agriculture. historic convictions of animal abusers. This hard-fought progress has been made Our brand new corporate outreach possible because of you—MFA’s cherished department is giving animals a much- members. Every day I am grateful to each needed voice in the boardrooms of some of you for your generous and unwavering of the country’s largest and most powerful support. Together we are truly building a companies. In the past year, MFA has kinder future for all creatures. Thank you for pressured major corporations—including paving the way. Costco, Kmart, and Kraft Foods—to implement new policies that will reduce the With gratitude, suffering of millions of pigs and cows. MFA’s educational outreach campaigns are helping consumers from coast to coast see farmed animals in a new light. -

All Creation Groans: the Lives of Factory Farm Animals in the United States

InSight: RIVIER ACADEMIC JOURNAL, VOLUME 13, NUMBER 1, SPRING 2017 “ALL CREATION GROANS”: The Lives of Factory Farm Animals in the United States Sr. Lucille C. Thibodeau, pm, Ph.D.* Writer-in-Residence, Department of English, Rivier University Today, more animals suffer at human hands than at any other time in history. It is therefore not surprising that an intense and controversial debate is taking place over the status of the 60+ billion animals raised and slaughtered for food worldwide every year. To keep up with the high demand for meat, industrialized nations employ modern processes generally referred to as “factory farming.” This article focuses on factory farming in the United States because the United States inaugurated this approach to farming, because factory farming is more highly sophisticated here than elsewhere, and because the government agency overseeing it, the Department of Agriculture (USDA), publishes abundant readily available statistics that reveal the astonishing scale of factory farming in this country.1 The debate over factory farming is often “complicated and contentious,”2 with the deepest point of contention arising over the nature, degree, and duration of suffering food animals undergo. “In their numbers and in the duration and depth of the cruelty inflicted upon them,” writes Allan Kornberg, M.D., former Executive Director of Farm Sanctuary in a 2012 Farm Sanctuary brochure, “factory-farm animals are the most widely abused and most suffering of all creatures on our planet.” Raising the specter of animal suffering inevitably raises the question of animal consciousness and sentience. Jeremy Bentham, the 18th-century founder of utilitarianism, focused on sentience as the source of animals’ entitlement to equal consideration of interests. -

Why Vegan Becoming Vegan Is a Powerful Way to Oppose Cruelty to Animals the Animals We Eat

WHY VEGAN Becoming Vegan Is A Powerful Way To Oppose Cruelty To Animals THE ANIMALS WE EAT We love dogs and cats, and make them part of our families—if we were to witness them being slaughtered as farm animals are we’d be horrified. Yet pigs, cows, and chickens also have individual personalities, feel pain, and fear danger. Protecting dogs and cats while exploiting cows, pigs, and chickens is speciesism—harming individuals because they belong to a different species. If it’s wrong to kill our companion animals for food, then it’s also wrong to kill chickens and pigs, as there are no morally significant differences between them. Our society turns a blind eye to farm animals—but it’s time for that to change. Fortunately, you don’t need to eat animal foods to be healthy or to have high- protein, satisfying meals. There are even plant-based versions of most of your favorite comfort foods. Read on to find out how going vegan can help fight speciesism! “ Many of the nation’s most routine animal farming practices would be illegal if perpetrated against cats and dogs.” Jonathan Lovvorn, Chief Counsel, The Humane Society of the United States Male chicks being dropped into a grinding machine. MEET SCARLEtt Like all chickens, Scarlett has a unique personality. Studies show that chickens also have a sense of time and they anticipate the future. Scarlett was raised for her eggs in a cage-free facility and was suffering terribly when she was rescued, but now she lives in a loving home. -

Vegetarian Starter Kit You from a Family Every Time Hold in Your Hands Today

inside: Vegetarian recipes tips Starter info Kit everything you need to know to adopt a healthy and compassionate diet the of how story i became vegetarian Chinese, Indian, Thai, and Middle Eastern dishes were vegetarian. I now know that being a vegetarian is as simple as choosing your dinner from a different section of the menu and shopping in a different aisle of the MFA’s Executive Director Nathan Runkle. grocery store. Though the animals were my initial reason for Dear Friend, eliminating meat, dairy and eggs from my diet, the health benefi ts of my I became a vegetarian when I was 11 years old, after choice were soon picking up and taking to heart the content of a piece apparent. Coming of literature very similar to this Vegetarian Starter Kit you from a family every time hold in your hands today. plagued with cancer we eat we Growing up on a small farm off the back country and heart disease, roads of Saint Paris, Ohio, I was surrounded by which drastically cut are making animals since the day I was born. Like most children, short the lives of I grew up with a natural affi nity for animals, and over both my mother and time I developed strong bonds and friendships with grandfather, I was a powerful our family’s dogs and cats with whom we shared our all too familiar with home. the effect diet can choice have on one’s health. However, it wasn’t until later in life that I made the connection between my beloved dog, Sadie, for whom The fruits, vegetables, beans, and whole grains my diet I would do anything to protect her from abuse and now revolved around made me feel healthier and gave discomfort, and the nameless pigs, cows, and chickens me more energy than ever before. -

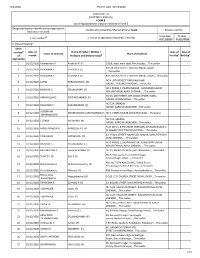

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applica Ons For

12/2/2020 Form9_AC6_02/12/2020 ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where applicaons Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Avadi Revision identy have been received) From date To date @ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 1. List number 01/12/2020 01/12/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial $ Date of Name of Father / Mother / Date of Time of number Name of claimant Place of residence of receipt Husband and (Relaonship)# hearing* hearing* applicaon 1 01/12/2020 Manikandan K Krishnan R (F) 135/8, avadi main road, Paruthipau, , Thiruvallur #20, BOUND STREET, KOVILPATHAGAI, AVADI 2 01/12/2020 PRASANNA E ELANGO R (F) , , Thiruvallur 3 01/12/2020 PRASANNA E ELANGO R (F) #20, BOUND STREET, KOVILPATHAGAI, AVADI, , Thiruvallur NO 6 , 8TH STREET THIRUVALLUVAR 4 01/12/2020 LATHA PARAMASIVAM (H) NAGAR, THIRUMULLAIVOYAL, , Thiruvallur NO 5 PHASE 1, SWATHI NAGAR , KANNADAPALAYAM 5 01/12/2020 BHAVANI S SELVAKUMAR (F) KOVILPATHAGAI AVADI CHENNAI , , Thiruvallur NO 26, 2ND STREET, 4TH CROSS STREET, INDRA 6 01/12/2020 AMANULLAH S SYED MOHAMED (F) NAGAR, CHOLAPURAM, , Thiruvallur NO 72A, SARADHI 7 01/12/2020 RAJAMANI C EAKAMBARAM (F) NAGAR, KARUNAKARACHERI, , Thiruvallur SUBISHANA 8 01/12/2020 DHARMAGURU LAKSHMANAN (F) NO 1, INDRA NAGAR, KOVILPADHAGAI, , Thiruvallur DHARMAGURU NO 72A, SARATHI 9 01/12/2020 C GIRIJA RAJAMANI (H) NAGAR, KARUNAKARACHERI, , Thiruvallur PLOT NO 91, 6 TH STREET THIRUMALAI VASAN NAGAR S 10 01/12/2020 MANU RAMESH R RAMESAN P G (F) M NAGAR POST, -

No Factory Farming Bailout Letter

The Honorable Mitch McConnell The Honorable Nancy Pelosi Majority Leader Speaker of the House United States Senate United States House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20510 Washington, D.C. 20515 The Honorable Chuck Schumer The Honorable Kevin McCarthy Minority Leader Minority Leader United States Senate United States House of Representatives Washington D.C. 20510 Washington, D.C. 20515 April 15, 2020 Dear Leader McConnell, Speaker Pelosi, Leader Schumer, Leader McCarthy, The public health toll of COVID-19 on so many in our nation is heart-wrenching. Congress must work to address the health crisis and protect those most at risk right now and in the months to come. Equally important, it must ensure we are prepared and resilient in the face of future crises. Food is essential to our health and resilience, yet this pandemic has exposed vulnerabilities in our food system and supply chains that demand attention and action. Many workers in the food chain as well as independent small and mid-size farmers are being disproportionately affected by the challenges of the COVID-19 crisis. We urge Congress to act now to ensure the protections included in its legislative response are extended to the food workers and producers on the frontlines of providing the food we all need to shelter-in-place in the coming weeks and sustain us in the future. As Congress turns its attention to investing in jobs and economic health, it must recognize the need to rebuild and grow local, sustainable food systems to support that vision. By investing in people and infrastructure to support these localized food systems, Congress can begin to improve food security, sustainability, health, and safety, as well as help address climate change. -

Rapid Reporting and the New Wave of Ag-Gag Laws

PUNISHING ANIMAL RIGHTS ACTIVISTS FOR ANIMAL ABUSE: RAPID REPORTING AND THE NEW WAVE OF AG-GAG LAWS MATTHEW SHEA* In the last few years, several states have proposed so-called “ag-gag” legis- lation. Generally, these bills have sought to criminalize (1) recording vid- eo or taking pictures of agricultural facilities without the consent of the owner and/or (2) entering an agricultural facility under false pretenses or misrepresenting oneself in job applications with the intent to commit an unauthorized act. These bills have gained little public support and have mostly been defeated in the past two years. However, a third type of ag- gag legislation is gaining traction in state legislatures across the country. This new type of law would require individuals to turn over any video footage of animal abuse to the police within 24, 48, or 120 hours of obtain- ing the evidence. Though these laws are promoted as a sincere effort to guard against animal abuse, critics argue that a pattern of abuse must be documented in order to build a strong case for prosecution, and that these industry-supported bills would force undercover journalists and activists to blow their cover after one incident, allowing facility owners and opera- tors to claim the incident was just a one-time occurrence. I. INTRODUCTION On January 30, 2008, the Humane Society of the United States released a video of workers at the Hallmark Meat Packing Company in Chino, California “kicking sick cows and using fork- lifts to force them to walk.”1 As a result, the now defunct * J.D. -

Sentinel Species: the Criminalization of Animal Rights Activists As Terrorists, and What It Means for the Civil Liberties in Trump's America

Denver Law Review Volume 95 Issue 4 Symposium: Animal Rights Article 5 November 2020 Sentinel Species: The Criminalization of Animal Rights Activists as Terrorists, and What It Means for the Civil Liberties in Trump's America Will Potter Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/dlr Recommended Citation Will Potter, Sentinel Species: The Criminalization of Animal Rights Activists as Terrorists, and What It Means for the Civil Liberties in Trump's America, 95 Denv. L. Rev. 877 (2018). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. SENTINEL SPECIES: THE CRIMINALIZATION OF ANIMAL RIGHTS ACTIVISTS AS "TERRORISTS," AND WHAT IT MEANS FOR CIVIL LIBERTIES IN TRUMP'S AMERICA WILL POTTERt ABSTRACT The animal rights movement has pioneered new, diverse forms of so- cial activism that have rapidly redefined how we view animals. But those remarkable successes have been met with an increasingly aggressive back- lash, including new terrorism laws, widespread surveillance, experimental prisons, and legislation explicitly criminalizing journalists and whistle- blowers. This Article will explain how, if left unchecked, these attacks on animal advocacy will become a blueprint for the wider criminalization of dissent. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION................................................ 878 I. MEET THE WORLD'S NEWEST TERRORIST .......... ............ 879 II. NUMBER ONE DOMESTIC TERRORISM THREAT ... .............. 882 III. MOBILIZING LAW ENFORCEMENT ...................... ....... 883 IV. ANIMAL ENTERPRISE TERRORISM............. ............... 887 V. FROM THE MARGINS TO THE MAINSTREAM: "AG-GAG" LAWS ..... -

INDIAN LITERATURE Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D

INDIAN LITERATURE Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D. Study Guide Description This course covers the literature of south Asia, from early Vedic Ages, and through classical time, and the rise of various empires. It also explores the rise of different religions and convergences of them, and then the transition from colonial control to independence. Students will analyze primary texts covering the genres of poetry, drama, fiction and non-fiction, and will discuss them from different critical stances. They will demonstrate their knowledge and understanding of the works by responding to questions focusing on the works, movements, authors, themes, and motifs. In addition, they will discuss the historical, social, cultural, or biographical contexts of the works‘ production. This course is intended for students who already possess a bachelor‘s and, ideally, a master‘s degree, and who would like to develop interdisciplinary perspectives that integrate with their prior knowledge and experience. About the Professor This course was prepared by Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D., research associate / research fellow, University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, Department of Languages and Cultures of South Asia. Contents Pre-classical Classical Early Post –classical Late Post-classical Early Modern 19th Century Early 20th Century Late 20th Century © 2017 by Humanities Institute PRE-CLASSICAL PERIOD POETRY Overview Pre-classical Indian literature contains two types of writing: poetry and commentary (which resembles the essay). These ancient texts (dating from about 1200 to 400 BCE) were composed, transmitted and recited in Sanskrit by Brahmin priests. It is poetry, however, that dominates the corpus of Vedic literature and is considered the more sacred style of expression. -

Ag-Gag” Laws from Broad Spectrum of Interest Groups

STATEMENT OF OPPOSITION TO PROPOSED “AG-GAG” LAWS FROM BROAD SPECTRUM OF INTEREST GROUPS We, the undersigned group of civil liberties, public health, food safety, environmental, food justice, animal welfare, legal, workers’ rights, journalism, and First Amendment organizations and individuals, hereby state our opposition to proposed whistleblower suppression laws, known as “ag-gag” bills, being introduced in states around the country. These bills seek to criminalize investigations of farms that reveal critical information about the production of animal products. These bills represent a wholesale assault on many fundamental values shared by all people across the United States. Not only would these bills perpetuate animal abuse on industrial farms, they would also threaten workers’ rights, consumer health and safety, law enforcement investigations and the freedom of journalists, employees and the public at large to share information about something as fundamental as our food supply. We call on state legislators around the nation to drop or vote against these dangerous and un-American efforts. American Civil Liberties Union Center for Science in the Public Interest American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty Citizens Action Coalition of Indiana to Animals (ASPCA) Clean Water Network Amnesty International Compassion In World Farming Animal Legal Defense Fund Compassion Over Killing Animal Welfare Institute The Community Environmental Legal Defense Association of Prosecuting Attorneys Fund A Well-Fed World Consumer Federation of America -

The Emergence of Modern Hinduism

1 Introduction Rethinking Religious Change in Nineteenth-Century South Asia For millennia, one of the most consistent characteristics of Hindu traditions has been variation. Scholarly work on contemporary Hinduism and its premodern antecedents ably captures this complexity, paying attention to a wide spectrum of ideologies, practices, and positions of authority. Studies of religion in ancient India stress doctrinal variation in the period, when ideas about personhood, liberation, the efficacy of ritual, and deities were all contested in a variety of texts and con- texts. Scholarship on contemporary Hinduism grapples with a vast array of rituals, styles of leadership, institutions, cultural settings, and social formations. However, when one turns to the crucial period of the nineteenth century, this complexity fades, with scholars overwhelmingly focusing their attention on leaders and move- ments that can be considered under the rubric “reform Hinduism.” The result has been an attenuated nineteenth-century historiography of Hinduism and a unilin- eal account of the emergence of modern Hinduism. Narratives about the emergence of modern Hinduism in the nineteenth century are consistent in their presumptions, form, and content. Important aspects of these narratives are familiar to students who have read introductory texts on Hinduism, and to scholars who write and teach those texts. At the risk of present- ing a caricature of these narratives, here are their most basic characteristics. The historical backdrop includes discussions of colonialism, Christian missions, and long- standing Hindu traditions. The cast of characters is largely the same in every account, beginning with Rammohan Roy and the Brahmo Samaj, moving on to Dayananda Saraswati and the Arya Samaj, and ending with Swami Vivekananda’s “muscular” Hinduism. -

A Novel Approach to Harness Maximum Power from Solar PV Panel 10-16 G

EDITORIAL Dear Members, Fellow Professionals, Friends and Well wishers, The Profession of ‘Electrical Installation Engineer’ revolves around Technology, Efficiency and Safety. Safety and Reliability are of utmost Concern with equal concern for Technology and Efficiency as they direct us to Better Controls and Conservation. 11th of May is marked as “National Technology Day” and let us remember that the Technological Inventions and Improvements have, in fact, been the cause for all our Galloping Developments over the past 150 years, but ;Challenges’ continue to remain. One of the important challenges is the “Storage of Electricity” and the solutions available at present are Storage Batteries of Lead Acid and other types with their limitations of capacities and weights and Life etc. Continuous researches are taking place all over the World and even as recently as April ’13, some land mark successes have been achieved. Announcement of successful design of low-cost, long-life battery that could enable solar and wind energy to become major suppliers to the electrical grid has come as a step forward. Currently the electrical grid cannot tolerate large and sudden power fluctuations caused by wide swings in sunlight and wind. As solar and wind’s combined contributions to an electrical grid approach 20 percent, energy storage systems must be available to smooth out the peaks and valleys of this “intermittent” power — storing excess energy and discharging when input drops. For solar and wind power to be used in a significant way, we need a battery made of economical materials that are easy to scale and still efficient, and it is believed that the new battery may be the best yet designed to regulate the natural fluctuations of these alternative energies.