INDIAN LITERATURE Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

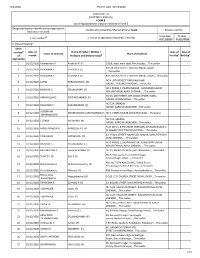

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Ramayan Around the World Ravi Kumar [email protected]

Ramayan Around The World Ravi Kumar [email protected] , Contents Acknowledgement.......................................................................................................2 The Timeless Tale .......................................................................................................2 The Universal Relevance of Ramayan .........................................................................2 Ramayan Scriptures in South East Asian Languages....................................................5 Ramayana in the West .................................................................................................6 Ramayan in Islamic Countries .....................................................................................7 Ramayan in Indonesia Islam is our Religion but Ramayan is our Culture..............7 Indonesia Ramayan Presented in Open Air Theatres ................................................9 Ramayan in Malaysia We Rule in the name of Ram’s Paduka.............................10 Ramayan among the Muslims of Philippines..........................................................11 Persian And Arabic Ramayan ................................................................................11 The Borderless Appeal of Ramayan.......................................................................13 Influence of Ramayan in Asian Countries..................................................................16 Influence of Ramayan in Cambodia .......................................................................17 -

Page 1 of 100 ALL INDIA ORIENTAL CONFERENCE LIFE MEMBERSHIP LIST

ALL INDIA ORIENTAL CONFERENCE LIFE MEMBERSHIP LIST PATRON: BENEFACTOR: 8. Atul Kumar 1. Arshad Jamal C7 Shiv Vihar Lal Mandir 1. Vimal Devi Rai 4, Mohalla - Prema Rai Colony Jwalapur, City : Head & Reader in Sanskrit. Maunath Bhanjan, Dist. Jwalapur, Taluka : Jwalapur Department. Hindu P. G. Maunathbhanjan, Uttar , District: Haridwar , College, Zamania, Dt. Pradesh 275101 Uttaranchal , Pin : 249407 Ghazipur 232 331 Patron -2070 Patron – 2238 Benefactor. - 497. 2. Shivala 9. Gauranga Das 2. S. Kalyanaraman Via Bhitauli Bazar Sri Sri Radha Gopinath 5/3 Temple Avenue, Luxmipur Shivala, Temple, 7 K.m. Munshi Srinagar Colony, Tal : Ghughli , Dist. Marg, Opposite Bhartiya Saidapet, Chennai 600 015 Maharajganj Uttar Pradesh , Vidyabhavan, Mumbai, Benefactor Pin : 273302 Mumbai, Maharashtra Patron-2075 400007 3. Shrama Sushma, Patron – 2410 H. No. 225 Bashirat Ganj, 3. Kapil Dev Lucknow 226004 U.P. P G. Department Of Sanskrit 10. Anand Suresh Kumar Benefactor – 1318 University Of Jammu , City : C/o Suddhanand Ashram Jammu, Taluka : Jammu Self knowledge, Village Giri 4. Kavita Jaiswal And Kashmir , District : Valam Adi Annamalai Road, B 5/11 , City : Awadhgarvi Jammu , Jammu And Tiruvannamalai, Sonarpura, Kashmir , Pin : 180006 Tamil Nadu 606604 Taluka : Varanasi , District : Patron-2087 Patron -1171 Varanasi , Uttar Pradesh , Pin : 221001 4. Shailendra Tiwari 11. Arora Mohini Benefactor -2125 D-36/25 B Godwoliya Gurudevi Vidyalaya Agastya Kund Near Sharda Ram Nagar Morar, 5. Dr Sathian M Bhawan , Varanasi, Uttar Gwalior M.P. 474006 Harinandanam,house,kairali Pradesh, 221001 Patron – 1302 Street,pattambi, City : Patron – 2114 Pattambi, Taluka : Pattambi , 12. Basu Ratna District : Palakkad , Kerala , 5. Pankaj Kumar Panday 183 Jodhpur Park, Pin : 679306 Vill- Nayagaw Tulasiyan Backside Bldg. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Compassion for Living Creatures in Indian Law Courts

religions Article Compassion for Living Creatures in Indian Law Courts Gilles Tarabout Director of Research (Emeritus), National Centre for Scientific Research, 75016 Paris, France; [email protected] Received: 27 March 2019; Accepted: 10 June 2019; Published: 14 June 2019 Abstract: The Constitution of India through an amendment of 1976 prescribes a Fundamental Duty ‘to have compassion for living creatures’. The use of this notion in actual legal practice, gathered from various judgments, provides a glimpse of the current debates in India that address the relationships between humans and animals. Judgments explicitly mentioning ‘compassion’ cover diverse issues, concerning stray dogs, trespassing cattle, birds in cages, bull races, cart-horses, animal sacrifice, etc. They often juxtapose a discourse on compassion as an emotional and moral attitude, and a discourse about legal rights, essentially the right not to suffer unnecessary pain at the hands of humans (according to formulae that bear the imprint of British utilitarianism). In these judgments, various religious founding figures such as the Buddha, Mahavira, etc., are paid due tribute, perhaps not so much in reference to their religion, but rather as historical icons—on the same footing as Mahatma Gandhi—of an idealized intrinsic Indian compassion. Keywords: India; animal welfare; compassion; Buddhism; court cases In 1976, the 42nd Amendment to the Constitution of India introduced a new section detailing various Fundamental Duties1 that citizens were to observe. One of these duties is ‘to protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers and wild life, and to have compassion for living creatures’ (Constitution of India, Part IV-A, Art. -

The Lord and His Land

Orissa Review * June - 2006 The Lord and His Land Dr. Nishakar Panda He is the Lord of Lords. He is Jagannath. He century. In Rajabhoga section of Madala Panji, is Omniscient, Omnipotent and Omnipresent. Lord Jagannatha has been described as "the He is the only cult, he is the only religion, he king of the kingdom of Orissa", "the master is the sole sect. All sects, all 'isms', all beliefs or the lord of the land of Orissa" and "the god and all religions have mingled in his eternal of Orissa". Various other scriptures and oblivion. He is Lord Jagannatha. And for narrative poems composed by renowned poets Orissa and teeming millions of Oriyas are replete with such descriptions where He is the nerve centre. The Jagannatha has been described as the institution of Jaganatha sole king of Orissa. influences every aspect of the life in Orissa. All spheres of Basically a Hindu our activities, political, deity, Lord Jagannatha had social, cultural, religious and symbolized the empire of economic are inextricably Orissa, a collection of blended with Lord heterogeneous forces and Jagannatha. factors, the individual or the dynasty of the monarch being A Political Prodigy : the binding force. Thus Lord Lord Jaganatha is always Jagannatha had become the and for all practical proposes national deity (Rastra Devata) deemed to be the supreme besides being a strong and monarch of the universe and the vivacious force for integrating Kings of Orissa are regarded as His the Orissan empire. But when the representatives. In yesteryears when Orissa empire collapsed, Lord Jagannatha had been was sovereign, the kings of the sovereign state seen symbolizing a seemingly secular force of had to seek the favour of Lord Jaganatha for the Oriya nationalism. -

Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science

A STUDY OF ELECTORAL PARTICIPATION OF BAHUJAN SAMAJ PARTY IN UTTAR PRADESH SINCE 1996 Thesis Submitted For the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Political Science By Mohammad Amir Under The Supervision of DR. MOHAMMAD NASEEM KHAN DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) Department Of Political Science Telephone: Aligarh Muslim University Chairman: (0571) 2701720 AMU PABX : 2700916/27009-21 Aligarh - 202002 Chairman : 1561 Office :1560 FAX: 0571-2700528 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Mr. Mohammad Amir, Research Scholar of the Department of Political Science, A.M.U. Aligarh has completed his thesis entitled, “A STUDY OF ELECTORAL PARTICIPATION OF BAHUJAN SAMAJ PARTY IN UTTAR PRADESH SINCE 1996”, under my supervision. This thesis has been submitted to the Department of Political Science, Aligarh Muslim University, in fulfillment of requirement for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. To the best of my knowledge, it is his original work and the matter presented in the thesis has not been submitted in part or full for any degree of this or any other university. DR. MOHAMMAD NASEEM KHAN Supervisor All the praises and thanks are to almighty Allah (The Only God and Lord of all), who always guides us to the right path and without whose blessings this work could not have been accomplished. Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to Late Prof. Syed Amin Ashraf who has been constant source of inspiration for me, whose blessings, Cooperation, love and unconditional support always helped me. May Allah give him peace. I really owe to Prof. -

1 1. the Nineteenth Century Neo-Hindu Movement in India (A

1 1. The Nineteenth Century Neo-Hindu Movement in India (a. Raja Rammohan Roy, b. Jeremy Bentham, Governor-General William Bentinck, and Lord Thomas Macaulay c. Debendranath Tagore, d. Arumuga (Arumuka) Navalar, e. Chandra Vidyasagar, f. Pundit Iswar Dayananda Saraswati, g. Keshab Sen, h. Bankim Chatterji, i. Indian National Congress, j. Contemporary China) 2. Swami Vivekananda and the Historical Situation 3. Swami Vivekananda’s Response ---------------------------------------------- II. Swami Vivekananda and the Neo-Hindu Response 1. The Nineteenth Century Neo-Hindu Movement in India In order to get a better idea of the historical-cultural background and climate of the times in which Swami Vivekananda lived, we shall cover the Neo-Hindu movement that preceded his writings. As A. R. Desai (1915-94) indicated, the Muslim conquest of large sections of India involved a major change in who ruled the political regime. At that time efforts centered on forming a resistance to Muslim religious conversions of Hindus. The basic economic structure, and the self-sufficient village system where most of the people lived remained intact. The British coming to India was far more pervasive involving changes in all areas of life. It was a takeover by a modern nation embodying an industrial mode of production that far surpassed a traditional feudal economy. As a modern capitalist nation, Great Britain was politically and economically powerful, combining a strong sense of national unity with an advanced science and technology. Needless to say, this presented a far greater challenge for the preservation of Indian society and culture than any previous conquest. In India religion and social institutions and relations “had to be remodeled to meet the needs of the new society. -

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applica Ons For

12/2/2020 Form9_AC6_02/12/2020 ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where applicaons Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Avadi Revision identy have been received) From date To date @ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 1. List number 01/12/2020 01/12/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial $ Date of Name of Father / Mother / Date of Time of number Name of claimant Place of residence of receipt Husband and (Relaonship)# hearing* hearing* applicaon 1 01/12/2020 Manikandan K Krishnan R (F) 135/8, avadi main road, Paruthipau, , Thiruvallur #20, BOUND STREET, KOVILPATHAGAI, AVADI 2 01/12/2020 PRASANNA E ELANGO R (F) , , Thiruvallur 3 01/12/2020 PRASANNA E ELANGO R (F) #20, BOUND STREET, KOVILPATHAGAI, AVADI, , Thiruvallur NO 6 , 8TH STREET THIRUVALLUVAR 4 01/12/2020 LATHA PARAMASIVAM (H) NAGAR, THIRUMULLAIVOYAL, , Thiruvallur NO 5 PHASE 1, SWATHI NAGAR , KANNADAPALAYAM 5 01/12/2020 BHAVANI S SELVAKUMAR (F) KOVILPATHAGAI AVADI CHENNAI , , Thiruvallur NO 26, 2ND STREET, 4TH CROSS STREET, INDRA 6 01/12/2020 AMANULLAH S SYED MOHAMED (F) NAGAR, CHOLAPURAM, , Thiruvallur NO 72A, SARADHI 7 01/12/2020 RAJAMANI C EAKAMBARAM (F) NAGAR, KARUNAKARACHERI, , Thiruvallur SUBISHANA 8 01/12/2020 DHARMAGURU LAKSHMANAN (F) NO 1, INDRA NAGAR, KOVILPADHAGAI, , Thiruvallur DHARMAGURU NO 72A, SARATHI 9 01/12/2020 C GIRIJA RAJAMANI (H) NAGAR, KARUNAKARACHERI, , Thiruvallur PLOT NO 91, 6 TH STREET THIRUMALAI VASAN NAGAR S 10 01/12/2020 MANU RAMESH R RAMESAN P G (F) M NAGAR POST, -

The Life of Krishna Chaitanya

The Life of Krishna Chaitanya first volume of the series: The Life and Teachings of Krishna Chaitanya by Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center (second edition) Copyright © 2016 Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center All rights reserved. ISBN-13: 978-1532745232 ISBN-10: 1532745230 Our Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center is a non-profit organization, dedicated to the research, preservation and propagation of Vedic knowledge and tradition, commonly described as “Hinduism”. Our main work consists in publishing and popularizing, translating and commenting the original scriptures and also texts dealing with history, culture and the peoblems to be tackled to re-establish a correct vision of the original Tradition, overcoming sectarianism and partisan political interests. Anyone who wants to cooperate with the Center is welcome. We also offer technical assistance to authors who wish to publish their own works through the Center or independently. For further information please contact: Mataji Parama Karuna Devi [email protected], [email protected] +91 94373 00906 Contents Introduction 11 Chaitanya's forefathers 15 Early period in Navadvipa 19 Nimai Pandita becomes a famous scholar 23 The meeting with Keshava Kashmiri 27 Haridasa arrives in Navadvipa 30 The journey to Gaya 35 Nimai's transformation in divine love 38 The arrival of Nityananda 43 Advaita Acharya endorses Nimai's mission 47 The meaning of Krishna Consciousness 51 The beginning of the Sankirtana movement 54 Nityananda goes begging -

The Emergence of Modern Hinduism

1 Introduction Rethinking Religious Change in Nineteenth-Century South Asia For millennia, one of the most consistent characteristics of Hindu traditions has been variation. Scholarly work on contemporary Hinduism and its premodern antecedents ably captures this complexity, paying attention to a wide spectrum of ideologies, practices, and positions of authority. Studies of religion in ancient India stress doctrinal variation in the period, when ideas about personhood, liberation, the efficacy of ritual, and deities were all contested in a variety of texts and con- texts. Scholarship on contemporary Hinduism grapples with a vast array of rituals, styles of leadership, institutions, cultural settings, and social formations. However, when one turns to the crucial period of the nineteenth century, this complexity fades, with scholars overwhelmingly focusing their attention on leaders and move- ments that can be considered under the rubric “reform Hinduism.” The result has been an attenuated nineteenth-century historiography of Hinduism and a unilin- eal account of the emergence of modern Hinduism. Narratives about the emergence of modern Hinduism in the nineteenth century are consistent in their presumptions, form, and content. Important aspects of these narratives are familiar to students who have read introductory texts on Hinduism, and to scholars who write and teach those texts. At the risk of present- ing a caricature of these narratives, here are their most basic characteristics. The historical backdrop includes discussions of colonialism, Christian missions, and long- standing Hindu traditions. The cast of characters is largely the same in every account, beginning with Rammohan Roy and the Brahmo Samaj, moving on to Dayananda Saraswati and the Arya Samaj, and ending with Swami Vivekananda’s “muscular” Hinduism. -

A Novel Approach to Harness Maximum Power from Solar PV Panel 10-16 G

EDITORIAL Dear Members, Fellow Professionals, Friends and Well wishers, The Profession of ‘Electrical Installation Engineer’ revolves around Technology, Efficiency and Safety. Safety and Reliability are of utmost Concern with equal concern for Technology and Efficiency as they direct us to Better Controls and Conservation. 11th of May is marked as “National Technology Day” and let us remember that the Technological Inventions and Improvements have, in fact, been the cause for all our Galloping Developments over the past 150 years, but ;Challenges’ continue to remain. One of the important challenges is the “Storage of Electricity” and the solutions available at present are Storage Batteries of Lead Acid and other types with their limitations of capacities and weights and Life etc. Continuous researches are taking place all over the World and even as recently as April ’13, some land mark successes have been achieved. Announcement of successful design of low-cost, long-life battery that could enable solar and wind energy to become major suppliers to the electrical grid has come as a step forward. Currently the electrical grid cannot tolerate large and sudden power fluctuations caused by wide swings in sunlight and wind. As solar and wind’s combined contributions to an electrical grid approach 20 percent, energy storage systems must be available to smooth out the peaks and valleys of this “intermittent” power — storing excess energy and discharging when input drops. For solar and wind power to be used in a significant way, we need a battery made of economical materials that are easy to scale and still efficient, and it is believed that the new battery may be the best yet designed to regulate the natural fluctuations of these alternative energies.