Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

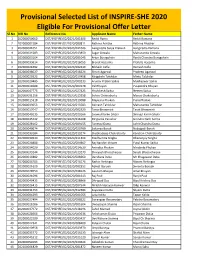

Provisional Selected List of INSPIRE-SHE 2020 Eligible For

Provisional Selected List of INSPIRE-SHE 2020 Eligible For Provisional Offer Letter Sl. -

The Mizoram Gazette EXTRA ORDINARY Published by Authority RNI No

The Mizoram Gazette EXTRA ORDINARY Published by Authority RNI No. 27009/1973 Postal Regn. No. NE-313(MZ) 2006-2008 Re. 1/- per page VOL - XLV Aizawl, Tuesday 1.11.2016 Kartika 10, S.E. 1938, Issue No. 448 ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi - 110001 Dated : 26th October, 2016 4 Kartika, 1938 (Saka) NOTIFICATION No. 56/2016/PPS-III - In pursuance of sub-paragraph (2) of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation & Allotment) Order, 1968, the Election Commission of India hereby makes the following further amendments to its Notification No. 56/2015/PPS-II dated 13th January, 2015, as amended from time to time, namely: - 1. In Table I (National Parties), appended to the said Notification - After the existing entries at Sl. No.6, the following entries shall be inserted under Column Nos. 1, 2, 3 & 4, respectively: - Sl.No. Name of the Party Symbol reserved Address 1. 2. 3. 4. 7 All India Trinamool Congress Flowers& Grass 30-B, Harish Chatterjee Street, Kolkata-700026 (West Bengal) 2. In Table II (State Parties), appended to the said Notification - (i) Against Sl. No.6 in respect of the State of Haryana, the existing entries under column No. 3, 4, and 5 pertaining to ‘Haryana Janhit Congress (BL)’, shall be deleted. (ii) Against Sl. No.2 in respect of the State of Arunachal Pradesh, the existing entries under column No. 3, 4, and 5 pertaining to ‘All India Trinamool Congress’, shall be deleted. (iii) Against Sl. No.12 in respect of the State of Manipur, the existing entries under column No. -

Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014

WID.world WORKING PAPER N° 2019/05 Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014 Abhijit Banerjee Amory Gethin Thomas Piketty March 2019 Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014 Abhijit Banerjee, Amory Gethin, Thomas Piketty* January 16, 2019 Abstract This paper combines surveys, election results and social spending data to document the long-run evolution of political cleavages in India. From a dominant- party system featuring the Indian National Congress as the main actor of the mediation of political conflicts, Indian politics have gradually come to include a number of smaller regionalist parties and, more recently, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). These changes coincide with the rise of religious divisions and the persistence of strong caste-based cleavages, while education, income and occupation play little role (controlling for caste) in determining voters’ choices. We find no evidence that India’s new party system has been associated with changes in social policy. While BJP-led states are generally characterized by a smaller social sector, switching to a party representing upper castes or upper classes has no significant effect on social spending. We interpret this as evidence that voters seem to be less driven by straightforward economic interests than by sectarian interests and cultural priorities. In India, as in many Western democracies, political conflicts have become increasingly focused on identity and religious-ethnic conflicts -

History of Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh at a glance Introduction Uttar Pradesh has multicultural, multiracial, fabulous wealth of nature-hills, valleys, rivers, forests, and vast plains. Viewed as the largest tourist destination in India, Uttar Pradesh boasts of 35 million domestic tourists. More than half of the foreign tourists, who visit India every year, make it a point to visit this state of Taj and Ganga. Agra itself receives around one million foreign tourists a year coupled with around twenty million domestic tourists. Uttar Pradesh is studded with places of tourist attractions across a wide spectrum of interest to people of diverse interests. The seventh most populated state of the world, Uttar Pradesh can lay claim to be the oldest seat of India's culture and civilization. It has been characterized as the cradle of Indian civilization and culture because it is around the Ganga that the ancient cities and towns sprang up. Uttar Pradesh played the most important part in India's freedom struggle and after independence it remained the strongest state politically. Geography Uttar Pradesh shares an international boundary with Nepal and is bordered by the Indian states of Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Mariana, Delhi, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Bihar. The state can be divided into two distinct hypsographical (altitude) regions. The larger Gangetic Plain region is in the north; it includes the Ganges-Yamuna Doab, the Ghaghra plains, the Ganges plains and the Terai. It has fertile alluvial soil and a flat topography (with a slope of 2 m/km) broken by numerous ponds, lakes and rivers. The smaller Vindhya Hills and plateau region is in the south. -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

BAIL (For Magistrates) S.S

1 BAIL (For Magistrates) S.S. Upadhyay Former District & Sessions Judge/ Former Addl. Director (Training) Institute of Judicial Training & Research, UP, Lucknow. Member, Governing Body, Chandigarh Judicial Academy, Chandigarh. Former Legal Advisor to Governor Raj Bhawan, Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow Mobile : 9453048988 E-mail : [email protected] Website: lawhelpline.in 1. Object of Bail u/s 437 or 439 CrPC : It has been laid down from the earliest time that the object of Bail is to secure the appearance of the accused person at his trial by reasonable amount of Bail. The object of Bail is neither punitive nor preventive. Deprivation of liberty must be considered a punishment unless it can be required to ensure that an accused person will stand his trial when called upon. The courts owe more than verbal respect to the principle that punishment begins after convictions, and that every man is deemed to be innocent until duly tried and duly found guilty. From the earlier times, it was appreciated that detention in custody pending completion of trial could be a cause of great hardship. From time to time, necessity demands that some unconvicted persons should be held in custody pending trial to secure their attendance at the trial but in such case 'necessity' is the operative test. In this country, it would be quite contrary to the concept of personal liberty enshrined in the constitution that any persons should be punished in respect of any matter, upon which, he has not been convicted or that in any circumstances, he should be deprived of his liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution upon only the belief that he will tamper with the witnesses if left at liberty, save in the most extraordinary circumstances. -

Module 1A: Uttar Pradesh History

Module 1a: Uttar Pradesh History Uttar Pradesh State Information India.. The Gangetic Plain occupies three quarters of the state. The entire Capital : Lucknow state, except for the northern region, has a tropical monsoon climate. In the Districts :70 plains, January temperatures range from 12.5°C-17.5°C and May records Languages: Hindi, Urdu, English 27.5°-32.5°C, with a maximum of 45°C. Rainfall varies from 1,000-2,000 mm in Introduction to Uttar Pradesh the east to 600-1,000 mm in the west. Uttar Pradesh has multicultural, multiracial, fabulous wealth of nature- Brief History of Uttar Pradesh hills, valleys, rivers, forests, and vast plains. Viewed as the largest tourist The epics of Hinduism, the Ramayana destination in India, Uttar Pradesh and the Mahabharata, were written in boasts of 35 million domestic tourists. Uttar Pradesh. Uttar Pradesh also had More than half of the foreign tourists, the glory of being home to Lord Buddha. who visit India every year, make it a It has now been established that point to visit this state of Taj and Ganga. Gautama Buddha spent most of his life Agra itself receives around one million in eastern Uttar Pradesh, wandering foreign tourists a year coupled with from place to place preaching his around twenty million domestic tourists. sermons. The empire of Chandra Gupta Uttar Pradesh is studded with places of Maurya extended nearly over the whole tourist attractions across a wide of Uttar Pradesh. Edicts of this period spectrum of interest to people of diverse have been found at Allahabad and interests. -

Development of Iconic Tourism Sites in India

Braj Development Plan for Braj Region of Uttar Pradesh - Inception Report (May 2019) INCEPTION REPORT May 2019 PREPARATION OF BRAJ DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR BRAJ REGION UTTAR PRADESH Prepared for: Uttar Pradesh Braj Tirth Vikas Parishad, Uttar Pradesh Prepared By: Design Associates Inc. EcoUrbs Consultants PVT. LTD Design Associates Inc.| Ecourbs Consultants| Page | 1 Braj Development Plan for Braj Region of Uttar Pradesh - Inception Report (May 2019) DISCLAIMER This document has been prepared by Design Associates Inc. and Ecourbs Consultants for the internal consumption and use of Uttar Pradesh Braj Teerth Vikas Parishad and related government bodies and for discussion with internal and external audiences. This document has been prepared based on public domain sources, secondary & primary research, stakeholder interactions and internal database of the Consultants. It is, however, to be noted that this report has been prepared by Consultants in best faith, with assumptions and estimates considered to be appropriate and reasonable but cannot be guaranteed. There might be inadvertent omissions/errors/aberrations owing to situations and conditions out of the control of the Consultants. Further, the report has been prepared on a best-effort basis, based on inputs considered appropriate as of the mentioned date of the report. Consultants do not take any responsibility for the correctness of the data, analysis & recommendations made in the report. Neither this document nor any of its contents can be used for any purpose other than stated above, without the prior written consent from Uttar Pradesh Braj Teerth Vikas Parishadand the Consultants. Design Associates Inc.| Ecourbs Consultants| Page | 2 Braj Development Plan for Braj Region of Uttar Pradesh - Inception Report (May 2019) TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER ......................................................................................................................................... -

India Assessment October 2002

INDIA COUNTRY REPORT October 2003 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM India October 2003 CONTENTS 1. Scope of Document 1.1 - 1.4 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.4 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.4 4. History 4.1 - 4.16 1996 - 1998 4.1 - 4.5 1998 - the present 4.6 - 4.16 5. State Structures 5.1 - 5.43 The Constitution 5.1 - Citizenship and Nationality 5.2 - 5.6 Political System 5.7. - 5.11 Judiciary 5.12 Legal Rights/Detention 5.13 - 5.18 - Death penalty 5.19 Internal Security 5.20 - 5.26 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.27 - 5.33 Military Service 5.34 Medical Services 5.35 - 5.40 Educational System 5.41 - 5.43 6. Human Rights 6.1 - 6.263 6.A Human Rights Issues 6.1 - 6.150 Overview 6.1 - 6.20 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.21 - 6.25 - Treatment of journalists 6.26 – 6.27 Freedom of Religion 6.28 - 6.129 - Introduction 6.28 - 6.36 - Muslims 6.37 - 6.53 - Christians 6.54 - 6.72 - Sikhs and the Punjab 6.73 - 6.128 - Buddhists and Zoroastrians 6.129 Freedom of Assembly & Association 6.130 - 6.131 - Political Activists 6.132 - 6.139 Employment Rights 6.140 - 6.145 People Trafficking 6.146 Freedom of Movement 6.147 - 6.150 6.B Human Rights - Specific Groups 6.151 - 6.258 Ethnic Groups 6.151 - Kashmir and the Kashmiris 6.152 - 6.216 Women 6.217 - 6.238 Children 6.239 - 6.246 - Child Care Arrangements 6.247 - 6.248 Homosexuals 6.249 - 6.252 Scheduled castes and tribes 6.253 - 6.258 6.C Human Rights - Other Issues 6.259 – 6.263 Treatment of returned failed asylum seekers 6.259 - 6.261 Treatment of Non-Governmental 6.262 - 263 Organisations (NGOs) Annexes Chronology of Events Annex A Political Organisations Annex B Prominent People Annex C References to Source Material Annex D India October 2003 1. -

Chapter-1 Introduction 1. Introduction

CHAPTER-1 INTRODUCTION 1. INTRODUCTION Education, in the broad sense, means preparation for life, it aims at all round development of individuals. Thus education is concerned with developing optimum organic health and emotional vitality such as social consciousness, acquisition of knowledge, wholesome attitude, moral and spiritual qualities.1 Education is also considered a process by which, individual is shaped to fit into the society to maintain and advance the social order. It is a system designed to make an individual rational, mature and a knowledgeable human being. Education is the modification of behaviour of an individual for the better adjustment in the society and for making a useful and worthwhile citizen. 2 The pragmatic view of education highlights learning by doing. Learning by doing takes place in the class room, in the library, on the play ground, in the gymnasium, or on the trips at home. 3 Civilized societies have always felt the need for physical education for its members except during the middle ages, when physical education as is typically known today found almost no place within the major educational pattern that prevailed. During the period, in Europe, asceticism in the early Christian church on the other hand set a premium on physical weakness in the vain hope that this was the path to spiritual excellence.4 During the middle age sports was associated with military motives, since many of the physical activities were designed to harden and strengthen man for combat5. The rapid development of physical education within the present century and the weighted influence accruing to some of its more spectacular activities suggest the imperative need, a clean understanding of unequal role, a well balanced programme in the field may give rise to the optimum growth and development of the youth. -

Unit 11 Leadership*

Party System and Electoral * Politics UNIT 11 LEADERSHIP Structure 11.0 Objectives 11.1 Introduction 11.2 Leadership during the Nehruvian Era (1950s to mid-1960s) 11.3 Emergence of the State Level Leadership 11.4 Leadership from the 1990s 11.5 Women Leadership 11.6 References 11.7 Let Us Sum Up 11.8 Answers to Check Your Progress 11.0 OBJECTIVES After reading this unit, you will be able to: Explain the meaning and significance of leadership in India; Identify the characteristics of leadership in Indian states; Discuss the changes in nature of leadership over the years after Independence; and Explain the process of emergence of leadership. 11.1 INTRODUCTION In a democracy, leadership is one of the important parts of the political system. It plays multiple roles. It helps articulate the interests of people, formulate policies for them; provide an ideological orientation when needed; chalk out strategies to mobilises them into collective action, and represent them in the elected bodies at different levels. These roles can be played as a single act by a single leader. Or different roles can be played by different leaders. Some leaders do not join a party or an institution formally. They lead people in an apolitical way, in the sense that, they do not form a party. In a culturally diverse society such as India, there are leaders that represent different identity groups – caste, language, region, gender or religion. They mostly focus on the issues that concern the specific group. Although they may also form a political party or contest elections, generally, they play the role of community leaders. -

Stamps of India - Commemorative by Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890

E-Book - 26. Checklist - Stamps of India - Commemorative By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 26. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 1st May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 76 Nos. YEAR PRICE NAME Mint FDC B. 1 2 3 1947 1 21-Nov-47 31/2a National Flag 2 15-Dec-47 11/2a Ashoka Lion Capital 3 15-Dec-47 12a Aircraft 1948 4 29-May-48 12a Air India International 5 15-Aug-48 11/2a Mahatma Gandhi 6 15-Aug-48 31/2a Mahatma Gandhi 7 15-Aug-48 12a Mahatma Gandhi 8 15-Aug-48 10r Mahatma Gandhi 1949 9 10-Oct-49 9 Pies 75th Anni. of Universal Postal Union 10 10-Oct-49 2a -do- 11 10-Oct-49 31/2a -do- 12 10-Oct-49 12a -do- 1950 13 26-Jan-50 2a Inauguration of Republic of India- Rejoicing crowds 14 26-Jan-50 31/2a Quill, Ink-well & Verse 15 26-Jan-50 4a Corn and plough 16 26-Jan-50 12a Charkha and cloth 1951 17 13-Jan-51 2a Geological Survey of India 18 04-Mar-51 2a First Asian Games 19 04-Mar-51 12a -do- 1952 20 01-Oct-52 9 Pies Saints and poets - Kabir 21 01-Oct-52 1a Saints and poets - Tulsidas 22 01-Oct-52 2a Saints and poets - MiraBai 23 01-Oct-52 4a Saints and poets - Surdas 24 01-Oct-52 41/2a Saints and poets - Mirza Galib 25 01-Oct-52 12a Saints and poets - Rabindranath Tagore 1953 26 16-Apr-53 2a Railway Centenary 27 02-Oct-53 2a Conquest of Everest 28 02-Oct-53 14a -do- 29 01-Nov-53 2a Telegraph Centenary 30 01-Nov-53 12a -do- 1954 31 01-Oct-54 1a Stamp Centenary - Runner, Camel and Bullock Cart 32 01-Oct-54 2a Stamp Centenary