UNIT-V I)Rajaram Mohan Rai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Books Details

1 Thumbnail Details A Brief History of Malayalam Language; Dr. E.V.N. Namboodiri The history of Malayalam Language in the background of pre- history and external history within the framework of modern linguistics. The author has made use of the descriptive analysis of old texts and modern dialects of Malayalam prepared by scholars from various Universities, which made this study an authoritative one. ISBN : 81-87590-06-08 Pages: 216 Price : 130.00 Availability: Available. A Brief Survey of the Art Scenario of Kerala; Vijayakumar Menon The book is a short history of the painting tradition and sculpture of Kerala from mural to modern period. The approach is interdisciplinary and tries to give a brief account of the change in the concept, expression and sensibility in the Art Scenario of Kerala. ISBN : 81-87590-09-2 Pages: 190 Price : 120.00 Availability: Available. An Artist in Life; Niharranjan Ray The book is a commentary on the life and works of Rabindranath Tagore. The evolution of Tagore’s personality – so vast and complex and many sided is revealed in this book through a comprehensive study of his life and works. ISBN : Pages: 482 Price : 30.00 Availability: Available. Canadian Literature; Ed: Jameela Begum The collection of fourteen essays on cotemporary Canadian Literature brings into focus the multicultural and multiracial base of Canadian Literature today. In keeping the varied background of the contributors, the essays reflect a wide range of critical approaches: feminist, postmodern, formalists, thematic and sociological. SBN : 033392 259 X Pages: 200 Price : 150.00 Availability: Available. 2 Carol Shields; Comp: Lekshmi Prasannan Ed: Jameela Begum A The monograph on Carol Shields, famous Canadian writer, is the first of a series of monographs that the centre for Canadian studies has designed. -

CONTEMPORARY INDIA and EDUCATION.Pdf

BHARATHIDASAN UNIVERSITY TIRUCHIRAPPALLI – 620 024 CENTRE FOR DISTANCE EDUCATION CONTEMPORARY INDIA AND EDUCATION B.Ed. I YEAR (Copyright reserved) For Private Circulation only Chairman Dr.V.M.Muthukumar Vice-Chancellor Bharathidasan University Tiruchirapplli-620 024 Vice-Chairman Dr.C.Thiruchelvam Registrar Bharathidasan University Tiruchirapplli-620 024 Course Director Dr. R. Babu Rajendran Director i/c Centre for Distance Education Bharathidasan University Tiruchirapplli-620 024 Course Material Co-ordinator Dr.K.Anandan Professor & Head, Dept .of Education Centre for Distance Education Bharathidasan University Tiruchirapplli-620 024 Author Dr.R.Portia Asst.Professor Alagappa University College of Education Karaikudi,Sivaganga(Dt.) The Syllabus adopted from 2015-16 onwards Core - II: CONTEMPORARY INDIA AND EDUCATION Internal Assessment: 25 Total Marks: 100 External Assessment: 75 Examination Duration: 3 hrs. Objectives: After the completion of this course the student teacher will be able 1. To understand the concept and aims of Education. 2. To develop understanding about the social realities of Indian society and its impact on education 3. To learn the concepts of social Change and social transformation in relation to education 4. To understand the educational contributions of the Indian cum western thinkers 5. To know the different values enshrined in the constitution of India and its impact on education 6. To identify the contemporary issues in education and its educational implications 7. To understand the historical developments in policy framework related to education Course Content: UNIT-I Concept and Aims Education Meaning and definitions of Education-Formal, non-formal and informal education Various levels of Education-Objectives-pre-primary, primary, secondary and higher secondary education and various statuary boards of education -Aims of Education in Contemporary Indian society Determinants of Aims of Education. -

Self Respect Movement Under Periyar

AEGAEUM JOURNAL ISSN NO: 0776-3808 SELF RESPECT MOVEMENT UNDER PERIYAR M. Nala Assistant Professor of History Sri Sarada College for Women (Autonomous), Salem- 16 Self Respect Movement represented the Dravidian reaction against the Aryan domination in the Southern Society. It also armed at liberating the society from the evils of religious, customs and caste system. They tried to give equal status to the downtrodden and give the social dignity, Self Respect Movement was directed by the Dravidian communities against the Brahmanas. The movement wanted a new cultural society more based on reason rather than tradition. It aimed at giving respect to the instead of to a Brahmin. By the 19th Century Tamil renaissance gained strength because of the new interest in the study of the classical culture. The European scholars like Caldwell Beschi and Pope took a leading part in promoting this trend. C.V. Meenakshi Sundaram and Swaminatha Iyer through their wirtings and discourse contributed to the ancient glory of the Tamil. The resourceful poem of Bharathidasan, a disciple of Subramania Bharati noted for their style, beauty and force. C.N. Annadurai popularized a prose style noted for its symphony. These scholars did much revolutionise the thinking of the people and liberate Tamil language from brahminical influence. Thus they tried resist alien influence especially Aryan Sanskrit and to create a new order. The chief grievance of the Dravidian communities was their failure to obtain a fair share in the administration. Among then only the caste Hindus received education in the schools and colleges, founded by the British and the Christian missionaries many became servants of the Government, of these many were Brahmins. -

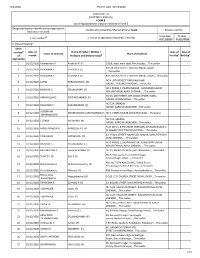

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

BHARATHIDASAN UNIVERSITY, TIRUCHIRAPPALLI 620 024 B.A. HISTORY Programme – Course Structure Under CBCS (Applicable to the Ca

BHARATHIDASAN UNIVERSITY, TIRUCHIRAPPALLI 620 024 B.A. HISTORY Programme – Course Structure under CBCS (applicable to the candidates admitted from the academic year 2010 -2011 onwards) Sem. Part Course Ins. Credit Exam Marks Total Hrs Hours Int. Extn. I Language Course – I (LC) – 6 3 3 25 75 100 Tamil*/Other Languages +# II English Language Course - I (ELC) 6 3 3 25 75 100 I III Core Course – I (CC) History of India 5 4 3 25 75 100 from Pre history to 1206 AD Core Course – II (CC) History of India 5 4 3 25 75 100 from 1206 -1707 AD First Allied Course –I (AC) – Modern 5 3 3 25 75 100 Governments I First Allied Course –II (AC) – Modern 3 - @ - - - Governments – II Total 30 17 500 I Language Course – II (LC) - 6 3 3 25 75 100 Tamil*/Other Languages +# II English Language Course – II (ELC) 6 3 3 25 75 100 II III Core Course – III(CC) History of Tamil 6 4 3 25 75 100 nadu upto 1801 AD First Allied Course – II (CC) - Modern 2 3 3 25 75 100 Governments – II First Allied Course – III (AC) – 5 4 3 25 75 100 Introduction to Tourism Environmental Studies 3 2 3 25 75 100 IV Value Education 2 2 3 25 75 100 Total 30 21 700 I Language Course – III (LC) 6 3 3 25 75 100 Tamil*/Other Languages +# II English Language Course - III (ELC) 6 3 3 25 75 100 III III Core Course – IV (CC) – History of 6 5 3 25 75 100 Modern India from 1707 - 1857AD Second Allied Course – I (AC) – Public 6 3 3 25 75 100 Administration I Second Allied Course – II (AC) - Public 4 - @ - -- -- Administration II IV Non Major Elective I – for those who 2 2 3 25 75 100 studied Tamil under -

Research Contributions of Faculty Members in State Universities of Tamil Nadu

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln November 2020 Research Contributions of Faculty members in State Universities of Tamil Nadu Jeyapragash Balasubramani Bharathidasan University, [email protected] Muthuraj Anbalagan Bharathidasan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Balasubramani, Jeyapragash and Anbalagan, Muthuraj, "Research Contributions of Faculty members in State Universities of Tamil Nadu" (2020). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 4546. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/4546 Research Contributions of Faculty members in State Universities of Tamil Nadu Dr.B.Jeyapragash1 Associate Professor, Department of Library and Information Science, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu, India. Email : [email protected] A.Muthuraj2 Ph.D Research Scholar, Department of Library and Information Science, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu, India. Email: [email protected] Abstract This study focuses on faculty member’s research productivity in State Universities of Tamil Nadu. The faculty member’s details were collected from 8 State Universities such as Alagappa University, Annamalai University, Bharathiar University, Bharathidasan University, Madurai Kamaraj University, Manonmaniam Sundaranar University, Periyar University and University of Madras. The Research productivity data were collected from Web of Science Database. It is found that total 1949 faculty members in different positions are available in State Universities of Tamil Nadu. It is also found that Annamalai University has highest number (654) of faculty members when compared to other universities. It is further analyzed that Annamalai University has published 3375 publications from Web of Science database by the present faculty members. -

PSC Assistant Engineer - Mechanical - Plantation Corporation of Kerala Ltd Examination Previous Year Question Paper

www.pscnet.in fb.com/pscnet.in PSC Assistant Engineer - Mechanical - Plantation Corporation Of Kerala Ltd Examination Previous Year Question Paper Exam Name: Assistant Engineer - Mechanical - Plantation Corporation Of Kerala Ltd Date of Test : 07.07.2015 Question Paper Code: 128/2015 Medium of Questions: English Join PSC WhatsApp Broadcast List : 90747 20773 www.pscnet.in fb.com/pscnet.in 128120L5 Maximum : 100 marks Time : I hour and lb minutes 1. The study which used to find a simpler, easier and better, way of performing a job is known as : (A) Motion study (B) Time study (C) Time and motion study (D) None of the above . 2. The critical path in PERT is determined on the basis of: (A) Maximum float of the each activity motion study (B) Minimum float of each activity (C) Slack of each event @) All of each above 3. The direct cost required to complete the activity in normal time duration is known as : (A) Normal cost (B) Minimum cost (C) Crash cost (D) None ofthe above 4. ABC analysis deals with : (A) Analysis of process chart (B) Controlling inventory material (C) Flow of material (D) None of the above 5. Critical path is that sequence of activities between the start and finish : (A) Shortest time (B) Normal time (C) Longest time (D) None of the above 6. IfC = original cost; S = scrap value, D = depreciation charges per year and N= number of years of useful Me, Then : (A) c=(s-r)/N (B) D=(s-c)/N (c) s=(D-N)ic (D) D=(c-s)/N 7. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Compassion for Living Creatures in Indian Law Courts

religions Article Compassion for Living Creatures in Indian Law Courts Gilles Tarabout Director of Research (Emeritus), National Centre for Scientific Research, 75016 Paris, France; [email protected] Received: 27 March 2019; Accepted: 10 June 2019; Published: 14 June 2019 Abstract: The Constitution of India through an amendment of 1976 prescribes a Fundamental Duty ‘to have compassion for living creatures’. The use of this notion in actual legal practice, gathered from various judgments, provides a glimpse of the current debates in India that address the relationships between humans and animals. Judgments explicitly mentioning ‘compassion’ cover diverse issues, concerning stray dogs, trespassing cattle, birds in cages, bull races, cart-horses, animal sacrifice, etc. They often juxtapose a discourse on compassion as an emotional and moral attitude, and a discourse about legal rights, essentially the right not to suffer unnecessary pain at the hands of humans (according to formulae that bear the imprint of British utilitarianism). In these judgments, various religious founding figures such as the Buddha, Mahavira, etc., are paid due tribute, perhaps not so much in reference to their religion, but rather as historical icons—on the same footing as Mahatma Gandhi—of an idealized intrinsic Indian compassion. Keywords: India; animal welfare; compassion; Buddhism; court cases In 1976, the 42nd Amendment to the Constitution of India introduced a new section detailing various Fundamental Duties1 that citizens were to observe. One of these duties is ‘to protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers and wild life, and to have compassion for living creatures’ (Constitution of India, Part IV-A, Art. -

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applica Ons For

12/2/2020 Form9_AC6_02/12/2020 ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where applicaons Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Avadi Revision identy have been received) From date To date @ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 1. List number 01/12/2020 01/12/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial $ Date of Name of Father / Mother / Date of Time of number Name of claimant Place of residence of receipt Husband and (Relaonship)# hearing* hearing* applicaon 1 01/12/2020 Manikandan K Krishnan R (F) 135/8, avadi main road, Paruthipau, , Thiruvallur #20, BOUND STREET, KOVILPATHAGAI, AVADI 2 01/12/2020 PRASANNA E ELANGO R (F) , , Thiruvallur 3 01/12/2020 PRASANNA E ELANGO R (F) #20, BOUND STREET, KOVILPATHAGAI, AVADI, , Thiruvallur NO 6 , 8TH STREET THIRUVALLUVAR 4 01/12/2020 LATHA PARAMASIVAM (H) NAGAR, THIRUMULLAIVOYAL, , Thiruvallur NO 5 PHASE 1, SWATHI NAGAR , KANNADAPALAYAM 5 01/12/2020 BHAVANI S SELVAKUMAR (F) KOVILPATHAGAI AVADI CHENNAI , , Thiruvallur NO 26, 2ND STREET, 4TH CROSS STREET, INDRA 6 01/12/2020 AMANULLAH S SYED MOHAMED (F) NAGAR, CHOLAPURAM, , Thiruvallur NO 72A, SARADHI 7 01/12/2020 RAJAMANI C EAKAMBARAM (F) NAGAR, KARUNAKARACHERI, , Thiruvallur SUBISHANA 8 01/12/2020 DHARMAGURU LAKSHMANAN (F) NO 1, INDRA NAGAR, KOVILPADHAGAI, , Thiruvallur DHARMAGURU NO 72A, SARATHI 9 01/12/2020 C GIRIJA RAJAMANI (H) NAGAR, KARUNAKARACHERI, , Thiruvallur PLOT NO 91, 6 TH STREET THIRUMALAI VASAN NAGAR S 10 01/12/2020 MANU RAMESH R RAMESAN P G (F) M NAGAR POST, -

INDIAN LITERATURE Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D

INDIAN LITERATURE Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D. Study Guide Description This course covers the literature of south Asia, from early Vedic Ages, and through classical time, and the rise of various empires. It also explores the rise of different religions and convergences of them, and then the transition from colonial control to independence. Students will analyze primary texts covering the genres of poetry, drama, fiction and non-fiction, and will discuss them from different critical stances. They will demonstrate their knowledge and understanding of the works by responding to questions focusing on the works, movements, authors, themes, and motifs. In addition, they will discuss the historical, social, cultural, or biographical contexts of the works‘ production. This course is intended for students who already possess a bachelor‘s and, ideally, a master‘s degree, and who would like to develop interdisciplinary perspectives that integrate with their prior knowledge and experience. About the Professor This course was prepared by Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D., research associate / research fellow, University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, Department of Languages and Cultures of South Asia. Contents Pre-classical Classical Early Post –classical Late Post-classical Early Modern 19th Century Early 20th Century Late 20th Century © 2017 by Humanities Institute PRE-CLASSICAL PERIOD POETRY Overview Pre-classical Indian literature contains two types of writing: poetry and commentary (which resembles the essay). These ancient texts (dating from about 1200 to 400 BCE) were composed, transmitted and recited in Sanskrit by Brahmin priests. It is poetry, however, that dominates the corpus of Vedic literature and is considered the more sacred style of expression.