The Perceptual Categorisation of Blended and Single Malt Scotch Whiskies Barry C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whiskey Compendium

WHISKEY COMPENDIUM Whiskey is a spirit distilled from fermented grains and aged in oak barrels, which give it most of its colour and flavour. Our whiskey compendium is a humble tribute to this great spirit that is made and enjoyed all around the world. “The water was not fit to drink. To make it palatable, we had to add whiskey. By diligent effort, I learned to like it.” - Winston Churchill - OUR COLLECTION 1 – AMERICAN WHISKEY 2 – TRADITIONAL (RYE) BOURBON 3 – WHEATED BOURBON 4 – SMALL BATCH BOURBON 5 – SINGLE BARREL BOURBON 6 – VINTAGE AND UNIQUE BOURBON 7 – TENNESSEE WHISKEY 8 – RYE WHISKEY 9 – OTHER AMERICAN WHISKEY 10 – SCOTCH WHISKY (WHERE IT ALL BEGAN) 11 – BLENDED WHISKY 12 – SINGLE MALTS OF SCOTLAND (SPEYSIDE) 13 – SINGLE MALTS OF SCOTLAND (HIGHLAND & LOWLAND) 14 – SINGLE MALTS OF SCOTLAND (ISLAY & CAMPBELTOWN) 15 – SINGLE MALTS OF SCOTLAND (THE ISLANDS) 16 – INDEPENDENT BOTTLERS 17 – RARE & PRESTIGIOUS 18 – WHISKEYS OF THE WORLD (IRELAND & CANADA) 19 – WHISKIES OF THE WORLD AMERICAN WHISKEY – 1 – A SHORT HISTORY OF WHISKY OR WHISKEY? AMERICAN WHISKEY The Irish and Americans spell American whiskey is regulated by some whiskey with an “e”. The of the strictest laws of any spirit in Scots, Japanese and Canadians the world. Its heritage began when early spell whisky without. American settlers preserved their extra rye crops by distilling them. Although different to the barley they were used to in Europe, rye still made damn good whiskey. It was in the 18th Centu r y, EASY DISTILLATION when a quarter of a million Scottish and Irish immigrants arrived, that Distillation is a way to separate alcohol whiskey became serious business and from water, by boiling fermented grains the tax collectors were, of course, (called mash) and condensing its vapour. -

2019 Scotch Whisky

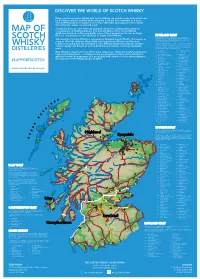

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

The Whiskey Machine: Nanofactory-Based Replication of Fine Spirits and Other Alcohol-Based Beverages

The Whiskey Machine: Nanofactory-Based Replication of Fine Spirits and Other Alcohol-Based Beverages © 2016 Robert A. Freitas Jr. All Rights Reserved. Abstract. Specialized nanofactories will be able to manufacture specific products or classes of products very efficiently and inexpensively. This paper is the first serious scaling study of a nanofactory designed for the manufacture of a specific food product, in this case high-value-per- liter alcoholic beverages. The analysis indicates that a 6-kg desktop appliance called the Fine Spirits Synthesizer, aka. the “Whiskey Machine,” consuming 300 W of power for all atomically precise mechanosynthesis operations, along with a commercially available 59-kg 900 W cryogenic refrigerator, could produce one 750 ml bottle per hour of any fine spirit beverage for which the molecular recipe is precisely known at a manufacturing cost of about $0.36 per bottle, assuming no reduction in the current $0.07/kWh cost for industrial electricity. The appliance’s carbon footprint is a minuscule 0.3 gm CO2 emitted per bottle, more than 1000 times smaller than the 460 gm CO2 per bottle carbon footprint of conventional distillery operations today. The same desktop appliance can intake a tiny physical sample of any fine spirit beverage and produce a complete molecular recipe for that product in ~17 minutes of run time, consuming <25 W of power, at negligible additional cost. Cite as: Robert A. Freitas Jr., “The Whiskey Machine: Nanofactory-Based Replication of Fine Spirits and Other Alcohol-Based Beverages,” IMM Report No. 47, May 2016; http://www.imm.org/Reports/rep047.pdf. 2 Table of Contents 1. -

WHISKEY AMERICAN WHISKEY Angel's Envy Port Barrel Finished

WHISK(E)YS BOURBON WHISKEY AMERICAN WHISKEY Angel's Envy Port Barrel Finished ............................................................ $12.00 High West Campfire Whiskey ................................................................... $10.00 Basil Hayden's ............................................................................................ $12.00 Jack Daniel's ............................................................................................... $8.00 Belle Meade Sour Mash Whiskey ............................................................. $10.00 Gentleman Jack ........................................................................................ $11.00 Belle Meade Madeira Cask Bourbon ........................................................ $15.00 George Dickel No.12 ................................................................................... $9.00 Blackened Whiskey .................................................................................... $10.00 Mitcher's American Whiskey .................................................................... $12.00 Buffalo Trace ............................................................................................... $8.00 Mitcher's Sour Mash Whiskey .................................................................. $12.00 Bulleit Bourbon ............................................................................................ $8.00 CANADIAN WHISKY Bulleit Bourbon 10 year old ...................................................................... $13.00 -

The Invicta Whisky Charter from the Distillers of Masthouse Whisky This

The Invicta Whisky Charter from the distillers of Masthouse Whisky This charter is made by Copper Rivet Distillery, England, distillers of Masthouse Whisky. English Whisky stands on the shoulders of the great whiskies from around the world and, as one of the founding distilleries of this revived tradition in England, we are making a commitment to consumers of our spirit that Masthouse Whisky is, and will always be, produced in accordance with these high standards. We do not believe that a tradition of exacting standards, high quality and innovation and experimentation are mutually exclusive. Our home of Chatham’s historic Royal Dockyard has demonstrated this over centuries, crafting and innovating to build world class ships. And we wish to set out areas where we intentionally leave latitude to create new and (or) nuanced expressions of this noble and beloved craft of whisky making. We believe that consumers have a right to know what they are buying and how what they consume and enjoy is produced made. Our commitment is that, when our whisky is chosen, it will have been made in strict adherence with these exacting standards designed to underpin character, flavour and quality. We don’t presume to lay out standards on behalf other great distilleries in other regions of England – we expect that they may wish to set their own rules and standards which underpin the character of their spirit. This is our charter, for our whisky. Our commitment, our promise, our standards – our charter The spirit must be distilled in England, United Kingdom. The entire process from milling grist, creating wort, fermenting distiller’s beer, distillation and filling casks must happen at the same site. -

An Important Notice: Due to Covid-19, We Have Temporarily Suspended Cash Payments and Are Currently Taking Card-Only Payments. Credit Card Surcharges Apply

MENU An important notice: Due to Covid-19, we have temporarily suspended cash payments and are currently taking card-only payments. Credit card surcharges apply SPEYSIDE Distilled 30ml. ABERLOUR A’BUNADH - - - - 61% 15 AUCHROISK 7 YEARS by Parkmore selection - - 2010 46% 10 AUCHROISK 11 YEARS 19 month ex-Oloroso Hogshead finish by James Eadie 2008 58.5% 14.5 AULTMORE 12 YEARS Official bottling - - - - 46% 15.5 AULTMORE 11 YEARS Single Hogshead by Blackadder - - 2006 57.6% 19.5 AULTMORE 1987 – 2007 by Scott’s Selection - - 1987 55.8% 37 AULTMORE 23 YEARS Ex-bourbon cask by Maltbarn - - 1997 49.9% 32.5 AULTMORE 14 YEARS by Whisky Galore - - - 1989 46% 39.5 AULTMORE 11 YEARS Bottled by High Spirits “Masters of Magic” - 2008 46% 15.5 THE BALVENIE 12 YEARS DOUBLE WOOD - - - 40% 11.5 THE BALVENIE 14 YEARS CARIBBEAN CASK - - - 43% 13.5 THE BALVENIE 12 YEARS “SWEET TOAST OF AMERICAN OAK” - - 43% 12 THE BALVENIE 14 YEARS “THE WEEK OF PEAT” - - - 48.3% 16 BENRIACH HEART OF SPEYSIDE - - - - 40% 9 BENRIACH 8 YEARS Single sherry butt by Carn Mor - - 2010 46% 11 BENRIACH 10 YEARS ‘Curiositas’ Peated - - - 46% 12 BENRIACH 9 YEARS Ex-Palo Cortado cask by James Eadie - - 2010 62.4% 26 BENRIACH “AUTHENTICUS” 30 YEAR OLD PEATED - - - 46% 68 BENRIACH 23 YEARS Ex-sherry butt by The Whisky Agency - 1997 50.7% 62 BENRINNES 11 YEARS Batch 10 by That Boutique-y whisky company - - 49% 18 BENRINNES 10 YEARS Sherry cask by Adelphi - - 2009 55.9% 21 BENRINNES 11 YEARS ex-Oloroso finish by James Eadie - - 2008 59.9% 27 BENRINNES 11 YEARS 7 month ex-PX Hogshead finish -

Questions & Answers

uk g. or y. k is h -w h c t o c s . w w Questions & Answers w The World of Scotch Whisky ORKNEY Kirkwall S E Thurso John D o'Groats I LEWIS R Stornoway Wick B E Lochinver H R Brora Ullapool E Bonar Bridge NORTH T UIST Tain U Invergordon Speyside Torridon O Dingwall Lossiemouth Elgin Portree SOUTH Buckie Banff Forres Fraserburgh UIST Nairn Macduff Keith Inverness Rothes Kyle of Lochalsh Craigellachie SKYE ly eau B ss e Grantown- Huntly N Dufftown h on-Spey c o Fort Augustus L y e Tomintoul Oldmeldrum p S Aviemore Inverurie Mallaig Aberdeen Dee Ballater Fort William Banchory Ben Nevis Loch Ericht 1343 m Stonehaven Tobermory Ballachulish Loch Pitlochry Rannoch Aberfeldy MULL Tay Montrose Blairgowrie Oban Loch Tay Arbroath Loch Awe Carnoustie Perth Dundee Inveraray Crieff Auchterarder Callander Loch Dunblane St Andrews Lochgilphead Lomond Stirling Kinross Glenrothes Helensburgh JURA Falkirk Port Askaig Greenock Dumbarton Tarbert EDINBURGH North ISLAY Berwick GLASGOW Port Ellen East Kilbride Brodick Berwick- Kilmarnock upon-Tweed Campbeltown ARRAN Troon Tweed Biggar Prestwick Melrose Coldstream Ayr Hawick Moffat Dumfries Stranraer Castle Douglas Wigtown Contents Introduction _____________________________________________ 2 - 3 The World's Leading Drink__________________________________ 4 - 7 The History of Scotch Whisky ______________________________ 8 - 10 Making Scotch Whisky ___________________________________ 11 - 19 The Importance of Blending ______________________________ 20 - 22 Scotch Whisky and the World _____________________________ -

Science of Smoke Studio Notes

9/15/18 SCIENCE OF SMOKE Dave Broom WELCOME Dave Broom was born in Glasgow and has spent his whole working life in the world of drink – from bottling line, to wine merchant, to real ale pub, to off licence, to Aussie wineries, to specialist spirits writing! Since then, Dave has written regularly about all spirit categories. Of his twelve books, two: ‘Drink: Never Mind the Peanuts’ and ‘Rum’ won the Glenfiddich award. His Whisky: The Manual was awarded Best Spirits Book at the Spirited Awards in 2015 and the ‘World Atlas of Whisky’ has been called “a landmark publication”. His most recent book, “The Way of Whisky: A Journey into Japanese Whisky’ appeared in 2017 and won the Andre Simon, John Avery Award. He is chief engineer for the go-to online site scotchwhisky.com, and writes for a large number of international titles. Dave has been involved with World Class since 2013, judging the Global Finals on a number of occasions as part of the World Class ‘gurus’ team’. JOHNNIE WALKER BLACK LABEL Johnnie Walker Black Label is the ‘Gold Standard’ of Blended Scotch Whisky. -Dave Broom 1 9/15/18 ORKNEY SKYE FOUR SPEYSIDE CORNERS HIGHLAND OF SCOTLAND • Diageo has over 10 million casks in storage • The largest holding of Scotch whisky in the world ISLAY LOWLAND • The only company to truly say they have whiskies from the four corners of Scotland CAMPBELTOWN MEET THE MAKERS Dr Jim Beveridge and the Whisky Masters Grain Milling Mashing Fermentation Distillation Maturation Blending WHISKY 2 9/15/18 THE PERFECT BLEND • Understanding how all liquids work in harmony • Balancing & matching flavors TASTING CAOL ILA GLENKINCHIE LAGAVULIN CARDHU TALISKER EARTHY FRESH CLYNELISH Iodine SMOKE FRUITS Fresh Apples Peat Smoke Pear Drops Kippers Cut Grass Bonfire Cinders Bubble Gum BENRINNES CAMERONBRIDGE ROYAL LOCHNAGAR PORT DUNDAS MORTLACH TROPICAL CREAMY Créme Caramel & RICH VANILLA Mango FRUITS Malted Milk Raisins Custard Figs Demerara Sugar SMOKE Smoke is the thread that runs through the fabric of Johnnie Walker whiskies. -

Beer. Flights

ﻣﻄﺒﺦ. .KITCHEN اﻟﻮﺟﺒﺎت اﻟﺨﻔﻴﻔﺔ وا¨ﻃﺒﺎق اﻟﺼﻐﻴﺮة BAR SNACKS & SMALL PLATES ﺳﻤﻚ ﺳﻠﻤﻮن ﻣﻄﻬﻮ ﺑﺎﻟﻮﻳﺴﻜﻲ ودﺑﺲ اﻟﺴﻜﺮ وﺷﻤﻨﺪر وﺑﻨﺪق A) Whisky-Cured Salmon, Treacle, Beetroot & Hazelnuts 80 80) ﻫﺎﻏﻴﺲ، ﻧﻴﺒﺲ وﺗﺎﺗﻴﺲ، ﺻﻮص اﻟﻮﻳﺴﻜﻲ ٧٠ A) Haggis, Neeps & Tatties 70) ﻓﻄﻴﺮة اﻟﺒﺮﻳﺪي، ﻣﺮق ﺻﻮص ﺑﻨﻲ ٦٠ Bridie Pie, Brown Sauce Gravy 60 رﻗﺒﺔ ﺣﻤﻞ "ﺣﺴﺎء ﻟﺤﻢ اﺳﻜﺘﻠﻨﺪي"، ﺷﻌﻴﺮ ﻟﺆﻟﺆي وأﻋﺸﺎب ٦٠ Lamb Neck “Scotch Broth”, Pearl Barley & Herbs 60 ﺳﺎﻧﺪوﻳﺘﺸﺎت ﺻﻐﻴﺮة ﻣﻦ ﻟﺤﻢ أﻧﺠﺲ وﺟﺒﻦ ﺗﺸﻴﺪر ﻣﺪﺧﻦ وﻣﺨﻠﻼت ٥٥ Mini Angus Sliders, Smoked Cheddar & Pickles 55 ﺑﻴﺾ اﺳﻜﺘﻠﻨﺪي، ﻣﺨﻠﻼت / Pairs perfectly with Dewar’s 12 Old Fashioned ٥٠ Scotch Egg, Piccalilli / Pairs perfectly with Dewar’s 12 Old Fashioned 50 ﻟﻔﺎﺋﻒ اﻟﺴﺠﻖ، ﻛﺎﺗﺸﺎب ﻣﺪﺧﻦ ٥٠ Sausage Rolls, Smoked Ketchup 50 ﻛﺮوﻛﻴﺖ ﺟﺒﻦ ﻣﺪﺧﻦ، ﻣﺮﺑﻰ ﻃﻤﺎﻃﻢ ٤٥ V) Smoked Cheese Croquettes, Tomato Jam 45) ﺷﺮاﺋﺢ ﺑﻄﺎﻃﺲ ﻣﻘﻠﻴﺔ وﻣﺎﻳﻮﻧﻴﺰ ﺑﺎﻟﻜﺎري ٣٥ V) Fat Chips, Curry Mayo 35) ﻃﺎوﻟﺔ اﻟﻤﺸﺎرﻛﺔ SHARING BOARD ﺳﺎﻧﺪوﻳﺘﺸﺎت ﺻﻐﻴﺮة وﻟﻔﺎﺋﻒ اﻟﺴﺠﻖ وﺑﻴﺾ اﺳﻜﺘﻠﻨﺪي وﻓﻄﺎﺋﺮ اﻟﺒﺮﻳﺪي ورﻗﺎﺋﻖ ﺑﻄﺎﻃﺲ ﻏﻨﻴﺔ ﺑﺎﻟﺪﻫﻮن Mini Angus Sliders, Sausage Rolls, Scotch Eggs, Bridie Pie & Fat Chips 200 200 ا¨ﻃﺒﺎق اﻟﻜﺒﻴﺮة BIG PLATES ﺿﻠﻊ ﻟﺤﻢ ﺑﻘﺮي وﺟﻌﺔ ﺑﻮرﺗﺮ وﻓﻄﻴﺮة اﻟﺒﺼﻞ اﻟﺮﻳﻔﻴﺔ اﻟﻤﺤﺸﻮة ﺑﻨﺨﺎع اﻟﻌﻈﺎم A) Beef Rib, Porter & Onion Cottage Pie, Bone Marrow 130 130) ﺳﻤﻚ ﺣﺪوق ُاﻟﻤﻐﻄﻰ ﺑﺠﻌﺔ اﻟﻤﺰر وﺷﺮاﺋﺢ اﻟﺒﻄﺎﻃﺲ وﻣﻬﺮوس اﻟﺒﺎزﻻء وﺻﻮص ﺗﺎرﺗﺎر ﺑﻪ ﻗﻄﻊ ﺳﻤﻴﻜﺔ .١١ A) Craft Ale Battered Haddock, Chips, Mushy Peas & Chunky Tartar Sauce 110) (V)ﺑﻴﺮﺟﺮ أﺑﺮدﻳﻦ أﻧﺠﺲ وﺟﺒﻦ ﺗﺸﻴﺪر ﻣﺪﺧﻦ وﻣﺨﻠﻼت وﺑﻄﺎﻃﺲ ﻣﺤﻤﺮة ﻋﻠﻰ ﺷﻜﻞ أرﺑﻄﺔ Aberdeen Angus Burger, Smoked Cheddar, Pickles & Shoestring Fries 95 95 رﻳﺰوﺗﻮ اﻟﺸﻌﻴﺮ اﻟﻠﺆﻟﺆي وﻓﻄﺮ ﺑﺮي وﺷﺮاﺋﺢ اﻟﺨﻀﺎر وﺟﺒﻦ ﺗﺸﻴﺪر ﻗﺪﻳﻤﺔ ٨٥ V)(A) Pearl Barley Risotto, Wild Mushroom, Vegetable Chips & Smoked Cheddar 85) ﺣﻠﻮﻳﺎت DESSERTS ﺟﺒﻦ وﺟﻴﻠﻲ ﺳﻔﺮﺟﻠﻲ وﺧﺒﺰ ﻣﺠﻔﻒ ﻓﻲ اﻟﻬﻮاء وﻋﻨﺐ Cheese Board, Quince Jelly, Air-Dried Breads & Grapes 45 45 ﻛﺮاﻧﺸﺎن ﺗﻮت اﻟﻌﻠﻴﻖ وﺷﻮﻓﺎن ﻣﺤﻤﺺ وﻋﺴﻞ Raspberry Cranachan, Toasted Oatmeal, Honey 40 40 (V) Vegetarian (A) Contains Alcohol ﺟﻤﻴﻊ ا¨ﺳﻌﺎر ﺑﺎﻟﺪرﻫﻢ اÀﻣﺎراﺗﻲ وﺗﺸﻤﻞ 7٪ رﺳﻮم اﻟﺒﻠﺪﻳﺔ ، 1٪. -

Exclusive, Rare, & Limited Release American Whiskey

EXCLUSIVE, RARE, & LIMITED RELEASE KNOB CREEK BOURBON AKER S ARK BLOOD OATH BOURBON, PACT NO. 4 M ’ M MOKY UARTZ OURBON KENTUCKY OWL 11 YEAR STRAIGHT RYE 2017 S Q V5 B MUGGLERS OTCH TRAIGHT OURBON MICHTER’S 10 YEAR KENTUCKY STRAIGHT RYE 2018 S ’ N S B IGGLY RIDGE MALL ARREL OURBON OCTOMORE 6.1 W B S B B OODFORD ESERVE OURBON OCTOMORE 8.3 W R B WILLIAM LARUE WELLER KENTUCKY STRAIGHT BOURBON 2017 TENNESSEE JACK DANIEL’S OLD NO. 7 AMERICAN WHISKEY JACK DANIEL’S GENTLEMAN JACK BEAT 3 RESERVE WHISKEY JACK DANIEL’S 150TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION GHOST OWL PACIFIC NORTHWEST WHISKEY JAILERS TENNESSEE WHISKEY MICHTER’S AMERICAN WHISKEY SEGRAMS 7 CROWN SMUGGLERS’ NOTCH LITIGATION WHEAT WHISKEY RYE STRANAHAN’S COLORADO WHISKEY ANGEL’S ENVY RYE WESTLAND SHERRY WOOD AMERICAN SINGLE MALT BASIL HAYDEN’S RYE BULLEIT RYE WHITE WHISKEY FLAG HILL STRAIGHT RYE MONADNOCK MOONSHINE HIGH WEST RENDEZVOUS RYE SMOKY QUARTZ GRANITE LIGHTNING HUDSON MANHATTAN RYE JAMES E. PEPPER 1776 STRAIGHT RYE BOURBON LOCK STOCK & BARREL STRAIGHT RYE WHISKY MICHTER’S STRAIGHT RYE 1792 SMALL BATCH BOURBON OLD OVERHOLT STRAIGHT RYE WHISKY AMADOR WHISKEY CO. DOUBLE BARREL BOURBON PUTNAM NEW ENGLAND RYE ANGEL’S ENVY BOURBON REDEMPTION RYE BASIL HAYDEN’S BOURBON TAMWORTH CHOCORUA STRAIGHT RYE BLANTON’S SINGLE BARREL TEMPLETON RYE BOOKER’S BOURBON WHISTLEPIG 10 YEAR STRAIGHT RYE BUFFALO TRACE KENTUCKY STRAIGHT BOURBON WHISTLEPIG FARMSTOCK BULLEIT BOURBON WHISTLEPIG THE BOSS HOG EAGLE RARE STRAIGHT BOURBON FLAG HILL STRAIGHT BOURBON HIGH WEST AMERICAN PRAIRIE CANADA HUDSON BABY BOURBON ALBERTA -

Scotch Whisky

Chapter 13 Scotch Whisky In This Chapter ▶ Noting the regional variations of Scotch ▶ Seeing how Scotch is made ▶ Listing some popular Scotch brands ▶ Savoring your Scotch cotch whisky (spelled without the e in whiskey) has a dis- Stinctive smoky flavor that’s the result of both the choice of ingredients and the method of distillation. Scotch whisky must be distilled and matured for at least three years in Scotland — but not necessarily bottled in Scotland. Some Scotch whiskies are distilled and aged in Scotland but bottled in another country. Types of Scotch Whisky Two kinds of Scotch whisky are distilled: malt whisky (from barley) and grain whisky (from cereals). Malt whiskies are divided into four groups according to the geographical loca- tion of the distillery in which they’re made (see Figure 13-1): ✓ Lowland malt whiskies: Made south of an imaginary line drawn from Dundee in the east to Greenock in the west. ✓ Highland malt whiskies: Made north of the aforemen- tioned line. 94 Part II: Distilling the High Points of Various Spirits ✓ Speyside malt whiskies: Made in the valley of the River Spey. Although these whiskies come from within the area of the Highland malt whiskies, the concentration of dis- tilleries and the specific climatic conditions in Speyside produce whiskies of an identifiable character, which is why they’re classified separately. ✓ Islay malt whiskies: Made on the island of Islay. Illustration by Lisa Reed Figure 13-1: The four main Scotch-producing regions. Part II: Distilling the High Points of Various Spirits Chapter 13: Scotch Whisky 95 Each group has its own clearly defined characteristics, rang- ing from the gentle, lighter-flavored Lowland whiskies to those distilled on Islay, which are generally regarded as the heaviest malt whiskies. -

Scotch Whisky Cereals Technical Note

- Scotch Whisky Cereals Technical Note 3rd Edition: August 2018 Scotch Whisky Cereals Technical Note Published by: The Scotch Whisky Association, Quartermile Two 2 Lister Square Edinburgh EH3 9GL Tel: 0131-222 9200 (Switchboard) E-mail: [email protected] 1st edition: January 2017 2nd edition: August 2017 3rd edition: August 2018 The text of the guidance has been drawn up by the Scotch Whisky Association and its Cereals Committee. Disclaimer This Technical Note has been provided as a document for information purposes only. It is aimed at those wishing to increase their knowledge of Scotch Whisky cereals. Decisions on procurement and the specification of cereals are ultimately a commercial matter for individual companies. The information contained in the guidance is correct at the time of going to print. © THE SCOTCH WHISKY ASSOCIATION 1 Scotch Whisky Cereals Technical Note Page CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 Introduction 3 Raw materials 3 Environmental sustainability 5 Assurance schemes 6 Commercial issues 7 Barley 9 Pot still distilling malt 9 Moisture content 11 Grain size, screenings and admixture 12 Grain damage 12 Viability 12 Nitrogen 12 Attributes for malt distilling barley 12 Grain distilling malt 14 Attributes for grain distilling barley 16 Development of new barley varieties 16 Research 16 Barley selection & testing 17 Spring barley varieties suitable for distilling 21 Wheat 23 Wheat varieties suitable for distilling 25 Attributes for distilling wheat varieties 29 Maize 30 Appendix 1 – General Scotch Whisky facts 31 Appendix 2 – Sources of information 33 Appendix 3 – Glossary of terms 35 2 Scotch Whisky Cereals Technical Note EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Scotch Whisky Association’s (SWA) membership accounts for around 90% of the sector and aims to create conditions for long-term growth worldwide and secure Scotch’s place as the leading high-quality spirit drink.