Beguinages:Flemish Invention in Thethirteenth Century. How

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Footloose in Flanders, Discovering One of the Seum That Is a Repository of Antwerp’S History but I Do Zip in Prettiest Regions of Europe in the Process

Travel BELGIUM Footloose in 1 2 Flanders A ROUND-UP OF THE FLEMISH TRIO OF BRUGES, GHENT AND ANTWERP. AND THEN AN OUTING TO BRUSSELS CHARUKESI R BY AMADURAI 3 4 f Eat, Pray, Love was a town, it would be Bruges. So pretty, so picture postcard that some guidebooks have described it as touristy and a tad fake. Our guide in Bruges splutters indig- nantly about the American who thought of it as a medieval Disneyland, asking him, “Is Bruges shut for winter?” Bruges is an-all weather destination, but to me, spring is the perfect time to be there. The tour- ist groups have just begun to trickle in, the daffodils are in full bloom at the charming Beguinage, FLANDERS where Benedictine nuns reside, and the weather makes me hum a happy tune all the time. FAIRYTALES: IAs I walk on the cobble-stoned lanes, I keep an ear open for the clip clop of horses ferrying tourists 1 The charm of across the UNESCO heritage town, the horseman (or in many cases, woman) doubling up as guide. Then, Bruges is in its canals there are the beguiling window displays on the chocolate shops lining the narrow shopping streets and lined by colourful the heady smell of Belgian frites (fries) in the air; together they erase all thoughts of calories and cho- buildings 2 Buskers lesterol from my mind. Remember, Eat is one of the leitmotifs for this town. are commonly found 5 To Pray, I head to the Church of Our Lady, to see Michelangelo’s sculpture of the Madonna and Child, in all Flanders cities in white Carrara marble. -

Appendix 1: Monastic and Religious Foundations in Thirteenth-Centur Y

APPENDIX 1: MONASTIC AND RELIGIOUS FOUNDATIONS IN THIRTEENTH-CENTURY FLANDERS AND HAINAUT Affiliation: Arrouaise Name Date of Foundation MenlWomen Eeckhout c. 1060/1146 Arrouaise Men Choques 1120/1138 Arrouaise Men Cysoing 855/1132 Arrouaise Men Phalernpin 1039/1145 Arrouaise Men Saint-Jean Baptiste c. 680/1142 Arrouaise Men Saint-Ni colas des Pres 1125/1140 Arrouaise Men Warneton 1066/1142 Arrouaise Men Zoetendale 1162/1215 re-founded Men Zonnebeke 1072/1142 Arrouaise Men Affiliation: Augustinian Canons Name Date of Foundation MenlWomen Saint-Aubert 963/1066 reforrned Men Saint-Marie, Voormezele 1069/1110 reforrned Men Saint-Martin, Ypres 1012/1102 reformed Men Saint-Pierre de Loo c. 1050/1093 reformed Men Saint-Pierre et Saint-Vaast c. 1091 Men Affiliation: Beguines Name Date cf Foundation MenlWomen Aardenburg 1249 Wornen Audenarde 1272 Wornen Bardonck, Y pres 1271/1273 Wornen Bergues 1259 Wornen 118 WOMEN, POWER, AND RELIGIOUS PATRONAGE Binehe 1248 Wornen Briel, Y pres 1240 Wornen Carnbrai 1233 Wornen Charnpfleury, Douai 1251 Wornen Damme 1259 Wornen Deinze 1273 Wornen Diksrnuide 1273 Wornen Ijzendijke 1276 Wornen Maubeuge 1273 Wornen Cantirnpre, Mons 1245 Wornen Orehies 1267 Wornen Portaaker (Ghent) 1273 Wornen Quesnoy 1246 Wornen Saint-Aubert (Bruges) 1270 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Courtrai) 1242 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Ghent) 1234 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Lilie) 1244/1245 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Valeneiennes) 1239 Wornen Ter Hooie (Ghent) 1262 Wornen Tournai 1241 Wornen Wetz (Douai) 1245 Wornen Wijngaard (Bruges) 1242 Wornen Affiliation: Benedictine Name Date oJ Foundation Men/Women Anehin 1079 Men Notre-Darne d'Avesnes 1028 Wornen Bergues Saint-Winoe 1028 Men Bourbourg c. 1099 Wornen Notre-Darne de Conde e. -

From Historic Centre to Design City on the Water CITY on the WATER

2016 2017 CAPTIVATING KORTRIJK from historic centre to design city on the water CITY ON THE WATER The banks of the Leie and the course of the Old Leie are the place to be! The green zone is ideal for young and old to enjoy some undisturbed peace. And in the middle of a city! The banks bring you wonderfully close to the fresh water and the moored pleasure craft, so that you can sit on one of the delightful terraces and almost feel the water. After the Middle Ages, the River Leie, and the linen and damask industry that grew up around it, played the leading role. Successfully too! From the 18th century Kortrijk enjoyed fame as the world centre for fl ax. Thanks to the creative entrepreneurship of its people, Kortrijk grew to become the vibrant, economic heart of the region. A new Leie needs new bridges. Seven impressive examples redraw the Kortrijk skyline and aff ord it a distinctive, imposing appearance. No boring or identical copies, but seven distinctive bridges that will help both visitors and locals orientate themselves. Sometimes majestic big city structures, at other times bold zigzags. 2 CITY ON THE WATER King Albertpark and skatebowl Texture, museum of Flax and river Lys Recently King Leopold III and his horse gaze over an open park Texture tells the rich story of fl ax in three totally diff erent and the renewed Leie banks. Th e park, which is bordered by rooms. You start in the Wonder Room: a fun laboratory about the lowered river banks, forms the transition between the city fl ax in your everyday life. -

The Beguine Option: a Persistent Past and a Promising Future of Christian Monasticism

religions Article The Beguine Option: A Persistent Past and a Promising Future of Christian Monasticism Evan B. Howard Department of Ministry, Fuller Theological Seminary 62421 Rabbit Trail, Montrose, CO 81403, USA; [email protected] Received: 1 June 2019; Accepted: 3 August 2019; Published: 21 August 2019 Abstract: Since Herbert Grundmann’s 1935 Religious Movements in the Middle Ages, interest in the Beguines has grown significantly. Yet we have struggled whether to call Beguines “religious” or not. My conviction is that the Beguines are one manifestation of an impulse found throughout Christian history to live a form of life that resembles Christian monasticism without founding institutions of religious life. It is this range of less institutional yet seriously committed forms of life that I am here calling the “Beguine Option.” In my essay, I will sketch this “Beguine Option” in its varied expressions through Christian history. Having presented something of the persistent past of the Beguine Option, I will then present an introduction to forms of life exhibited in many of the expressions of what some have called “new monasticism” today, highlighting the similarities between movements in the past and new monastic movements in the present. Finally, I will suggest that the Christian Church would do well to foster the development of such communities in the future as I believe these forms of life hold much promise for manifesting and advancing the kingdom of God in our midst in a postmodern world. Keywords: monasticism; Beguine; spiritual formation; intentional community; spirituality; religious life 1. Introduction What might the future of monasticism look like? I start with three examples: two from the present and one from the past. -

Sales Guide 2019 English Version © M

EN Sales Guide 2019 English version © M. Vanhulst The visit.brussels online sales guide is accessible to all, but is first and foremost aimed at professionals from the travel industry, namely tour operators, travel agents, coach companies and group organisers. It provides a complete overview of all activities and attractions in our city. These are then divided into specific themes which best represent Brussels, e.g. Art Nouveau, comics, heritage, etc. Each activity or attraction is explained in a file containing valuable information such as rates, contact details, languages in which the activity or attraction is provided, and much more. These files will allow travel professionals to take immediate action, should they wish to suggest an activity or attraction to their clients. The entire purpose of the sales guide is to advertise the tremendous potential of Brussels and boost creativity with travel professionals in order for them to perk up, enhance or change their offer whilst making them and their clients eager to discover and get a better idea of the city. Equally important, the sales guide limits research and hence lightens the workload considerably. In addition, the visit.brussels online sales guide obviously contains information on upcoming events, accommodation providers, coach parking details, visit.brussels contact information and other relevant data. We trust this unique tool will benefit all travel professionals worldwide and encourage them to choose Brussels as their preferred destination. Rest assured that we will keep on -

Welcome to the World Heritage City of Bruges

Welcome to the World Heritage City of Bruges There are places that somehow manage tant events and a complete summary of to get under your skin, even though you the Bruges museums, attractions and don’t really know them all that well. other sites of interest, including histor- Bruges is that kind of place. A warm and ical, cultural and religious buildings friendly place, a place made for people. and locations. Bruges’ beautiful A city whose history made it great, re- squares and enchanting canals are the sulting in a well-deserved classification regular backdrop for topclass cultural as a Unesco World Heritage site. events. And few cities have such a rich and diverse variety of museums, which 1 In this guide you will discover Bruges’ contain gems ranging from the Flemish FOREWORD different facets. There are five separate primitives and beautiful lace work to chapters. the finest modern art of today. In chapter 1 you will find everything you In Bruges you can dine at a different need to prepare your trip to Bruges. You star-rated restaurant each day, or per- will read about the ten must sees, get a haps you would prefer lunch at a trendy brief summary of the city’s history and bistro before wandering through the discover lots of practical information. winding cobbled streets of the city? Or Further in this chapter, the lovers of good maybe you just want to take in a pleasant food and drink will find a list of the best pub or one of the many magnificent ter- restaurants, while the shopaholics will races with a view? These are the places, receive tips for the most authentic and full of charm and character, which you top-quality shopping addresses. -

World Heritage City

BRUGES WORLD HERITAGE CITY 1 INTRODUCTION ruges is a unique city and is featured in the list of World Heritage Sites no less than four times. The historic centre of Bruges was acknowledged as a World Heritage Site on November 30th 2000. The Beguinage and the Belfry had already been included in the list in 1998 and 1999 respectively. In 2009 the Procession of the Holy Blood was recognized as Immaterial World Heritage. The title of World Heritage Site is a prestigious one. It puts the city on the international map and therefore holds additional cultural and tourist appeal. The city owes a lot to its past and its unique historical position. A city connected with the hanseatic league and the centre of European trade in the Middle Ages, Bruges is a compact city, densely built and with a wealth of art treasures. The unique architectural heritage has been carefully preserved throughout the centuries. In addition, Bruges boasts impressive museum collections, the most important of which is the collection of Flemish Primitives. Other treasures have been preserved in museums, churches, archives, foundations and the Municipal Public Library. The city also has a lot to offer in the field of immaterial heritage: the Procession of the Holy Blood recognised by Uneso, the Our Lady of Blindekens procession, the archers guilds, the musical traditions, to name only a few. This makes Bruges a paradise for those looking for additional value. The recognition as World Heritage is largely due to the architectural heritage, in particular because the city of Bruges is regarded as a ’textbook’ of architectural history, specifically of ‘Brick Gothic’. -

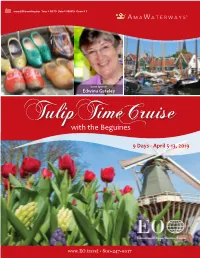

With the Beguines

www.EO.travel/mytrip Tour = RC19 Date = 040518 Code = T Guest Speaker Edwina Gateley TulipwithTime the BeguinesCruise 9 Days - April 5-13, 2019 www.EO.travel • 800-247-0017 - Roundtrip Amsterdam - April 5 – Depart USA learn about the beguinage’s unique history through their unique Board your overnight flight to Amsterdam. media displays. The very last beguine in the world, Marcella Pattyn, April 6 – ARRIVE IN AMSTERDAM, THE NETHERLANDS – resided in this beguinage from 1960-2005. (B,L,D) EMBARKATION - EO Exclusive Excursion April 10 – ANTWERP - EO Exclusive Excursion Welcome to Amsterdam. Visit the Beginhof (Begiunage of Explore this trendy city on a walking tour where you’ll see Antwerp’s Amsterdam) and see Amsterdam’s oldest preserved wooden house Steen Castle, Grote Market and Brabo Fountain, along with the built in 1465. Visit the Beginhof Kapel (Beguinage Chapel) built in UNESCO-designated Cathedral of Our Lady, where you can marvel at 1671 as a secret chapel for Catholics to worship in during Calvinist the works of the artist, Peter Paul Rubens. Next visit the Beguinage of rule. Transfer to the port to board your luxurious river cruise ship. Antwerp, built in 1545. The last Antwerp Beguine, Virginia Laeremans This evening, meet your fellow travelers on board at the Welcome lived here until her death in 1986. This is now a modern residential Dinner. (D) area but they have kept the original character of the 40 remaining April 7 – AMSTERDAM – HOORN houses, the tranquility of its 16th century garden and the name of Enjoy a scenic cruise through the Ijsselmeer to Hoorn, where you Saint Helige Martha on its gate preserved. -

World's Columbian Exposition, 1893 : Official Catalogue. Part X

> * * ■ . * * • / Official Catalogue /» OF EXHIBITS^ W ORIsD’S COLUMBIAN Exposition Department K. FlNB f\RTS» Chicago W. B. GONKEY COMPANY, PUBLISHERS TO THE EXPOSITION (A 1893 606 9 4 * f , i World’s Columbian Exposition 1893 ♦ OFFICIAL CATALOGUE Pf\RT X. ART GALLERIES and ANNEXES Department K. FINE ARTS Painting, Sculpture, Architecture,, DE.GORATION HALSEY G. IV&S, Chief » —— . .. • • • - ^ Edited by The Department of Publicity and Promotion M. P. HANDY, Chief CHICAGO: W. B. CONKEY COMPANY, PUBLISHERS TO THE World's Columbian exposition, 1693. 4 Entered according to Act of Congress in the year A. D. 1893, in the office of Librarian of Congress at Washington, D. C., by The World’s Columbian Exposition, For the exclusive use of W. B. Conkey Company, Chicago. This Catalogue presents the lists of exhibitors and exhibits as they were installed or accepted for installation, according to information filed with the editor of the Catalogue at the time of going to press. Additional entries, withdrawals, or changes in location of exhibits, will be noted in a subsequent edition. W. B. CONKEY COMPANY PRINTERS AND BINDERS CHICAGO. DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS. (K> HALSEY C. IVES, CHIEF. CHARLES M. KURTZ, ASSISTANT CHIEF. SARA T. HALLOWELL, ASSISTANT. LOUIS J. MILLET, SUPERINTENDENT OF ARCHITECTURAL AND DECORATIVE EXHIBITS GEORGE CORLISS, SUPERINTENDENT OF GALLERIES. I 6 DEPARTMENT K.—FINE ARTS. GROUP 143.—ENGRAVINGS AND ETCHINGS; PRINTS. FOR ETCHINGS NEW YORK. Carleton T. Chapman. C. F. W. Mielatz. Samuel Colman. C. A. Platt. James D. Smillie. PHILADELPHIA. Hermann Faber. Max Rosenthal. Bernhard Uhle. BOSTON. W. B. Closson. S. R. Koehler. Charles A. -

Unesco World Heritage Convention

Unesco World Heritage Convention Belgian efforts for global heritage care Unesco World Heritage Convention Belgian efforts for global heritage care Coverphoto's large: Marcel vanhulst © MrBC - above: © BeLSPO - center: Guy Focant © SPW - under: © onroerend erfgoed, photo oswald pauwels Foreword Dear reader, Soon Unesco will recognise a world heritage site for the thousandth time. Only sites with an Outstanding Universal Value are added to the World Heritage List. This recognition emphasises the general importance of the heritage site and the need to continue to protect it. Of the long list, everyone undoubtedly knows the Chinese wall, the Egyptian pyramids and the Taj Mahal in India. But do you also know the Belgian world heritage sites? Do you know what makes those sites so special? And do you know what efforts our country makes to help protect the world heritage in other places or continents? You will find the answers to all these questions in this brochure. However, this publication is also a beautiful example of the good cooperation between the different authorities and partners in Belgium, which I have been privileged enough to experience on a daily basis in the Permanent Delegation of Belgium to Unesco. My special thanks go to the Flemish Commission for Unesco and the Commission belge francophone et germanophone pour l'UNESCO, at whose initiative this brochure was compiled. Moreover, I would like to express my gratitude to the various partners to this project, in particular, Development Cooperation, Belgian Science Policy Office, the Walloon Heritage Institute, the Flanders Heritage Agency and the Directorate for Monuments and Sites of the Brussels-Capital Region. -

Resurrecting the 'Spiritual Daughters': the Houtappel Chapel And

chapter 8 Resurrecting the ‘Spiritual Daughters’: the Houtappel Chapel and Women’s Patronage of Jesuit Building Programs in the Spanish Netherlands Sarah Joan Moran On July 21 of 1640, the 100-year anniversary of the founding of the Jesuit order, a short but grand procession took place inside the Antwerp Jesuit church (Figs. 8.1, 8.2).1 Members of the community’s Marian sodality, a confraternity dedicated to the promotion of the cult of the Virgin, carried a statue of Our Lady of Scherpenheuvel (Fig. 8.3) from the church’s northern lateral chapel, where it had been kept temporarily, back to the southern chapel. The latter had been erected in c. 1620/21–1622 specifically to house this statue, and its walls had just recently been covered with panels of intricately carved, multicolored Italian marble.2 This stonework formed part of an integrated decorative scheme in which every surface was adorned with expensive materials and masterfully executed paintings and sculptures. By the middle of the seventeenth century it was arguably the finest space within an astonishingly richly appointed church, 1 This research was conducted with the support of the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study. 2 The event is described in a history of the city of Antwerp written by the Jesuit Daniel van Papenbroeck around 1700: ‘Apud Patres Societatis interea fiebat ingens apparatus, pro celebrando primo a sua institutione Iubilaeo, collaborantibus imprimis piis illis virginibus, quae sub illorum directione devotam Dea castitatem vitamque profitebantur. Praecelluerunt autem hoc in genere sorores Houtappeliae, quae providi a multis retro mensibus constituerant, fundatum a se piisque parentibus suis sacellum, communemque omnibus sub illius altari sepulturam quam speciosissime exornare marmoribus, qualibus iam ipsum altare circumcirca fulgebat, complexum eximiam penicelli Rubenii tabulam assumptae in coelum Virginis. -

Roots of Gender Equality: the Persistent Effect of Beguinages on Attitudes Toward Women

Roots of Gender Equality: the Persistent Effect of Beguinages on Attitudes Toward Women Annalisa Frigo1 and Eric` Roca Fern´andez∗2 1IRES/LIDAM, UCLouvain 2Aix-Marseille Univ., CNRS, EHESS, Centrale Marseille, AMSE, Marseille, France Abstract This paper is concerned with the historical roots of gender equality. It proposes and empirically assesses a new determinant of gender equality: gender-specific outside options in the marriage market. In particular, enlarging women's options besides marriage |even if only temporarily| increases their bargaining power with respect to men, leading to a persistent improvement in gender equality. We illustrate this mechanism focusing on Belgium, and relate gender-equality levels in the 19th century to the presence of medieval, female-only communities called beguinages that allowed women to remain single amidst a society that traditionally advocated marriage. Combining geo-referenced data on beguinal communities with 19th-century census data, we document that the presence of beguinages contributed to decrease the gender gap in literacy. The reduction is sizeable, amounting to a 12.3% drop in gender educational inequality. Further evidence of the beguinal legacy is provided leveraging alternative indicators of female agency. Keywords: Economic Persistence, Culture, Institutions, Religion, Gender Gap. JEL: I25, J16, N33, O15, O43, Z12. ∗We thank David de la Croix, Matteo Cervellati, Oded Galor, Marc Go~ni,Fabio Mariani, Felipe Valencia Caicedo, and all the participants to seminars at Brown University, Universit´ecatholique de Louvain, Universit´e du Luxembourg, the Indian Statistical Institute Delhi, Syddansk Universitet and Universit`aCommerciale Luigi Bocconi for precious comments and suggestions. Annalisa Frigo acknowledges the financial support from the Belgian French-speaking Community (convention ARC no15/19-063 on \Family Transformations: Incentives and Norms").