Roots of Gender Equality: the Persistent Effect of Beguinages on Attitudes Toward Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overzicht Hinder Voor Dienstverlening

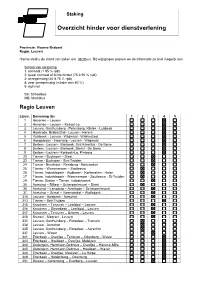

Staking Overzicht hinder voor dienstverlening Provincie: Vlaams-Brabant Regio: Leuven Hierna vindt u de stand van zaken om 06.00uur. Bij wijzigingen passen we de informatie zo snel mogelijk aan. Schaal van verstoring 1: normaal (+ 95 % rijdt) 2: quasi normaal of lichte hinder (75 à 95 % rijdt) 3: onregelmatig (40 à 75 % rijdt) 4: zeer onregelmatig (minder dan 40 %) 5: rijdt niet SB: Schoolbus MB: Marktbus Regio Leuven Lijnnr. Benaming lijn 1 2 3 4 5 1 Heverlee – Leuven 2 Heverlee – Leuven – Kessel-Lo 3 Leuven, Gasthuisberg - Pellenberg, Kliniek - Lubbeek 4 Haasrode, Brabanthal - Leuven - Herent 5 Vaalbeek - Leuven - Wijgmaal - Wakkerzeel 6 Hoegaarden - Neervelp - Leuven - Wijgmaal 7 Bertem - Leuven - Bierbeek, Sint-Kamillus - De Borre 8 Bertem - Leuven - Bierbeek, Bremt - De Borre 9 Bertem - Leuven - Korbeek-Lo, Pimberg 22 Tienen – Budingen – Diest 23 Tienen - Budingen - Sint-Truiden 24 Tienen - Neerlinter - Ransberg - Kortenaken 25 Tienen – Wommersom – Zoutleeuw 26 Tienen, Industriepark - Budingen - Kortenaken - Halen 27 Tienen, Industriepark - Wommersom - Zoutleeuw - St-Truiden 29 Tienen, Station – Tienen, Industriepark 35 Aarschot – Rillaar – Scherpenheuvel – Diest 36 Aarschot – Langdorp – Averbode – Scherpenheuvel 37 Aarschot – Gijmel – Varenwinkel – Wolfsdonk 310 Leuven - Holsbeek - Aarschot 313 Tienen – Sint-Truiden 315 Kraainem – Tervuren – Leefdaal – Leuven 316 Kraainem – Sterrebeek – Leefdaal – Leuven 317 Kraainem – Tervuren – Bertem – Leuven 318 Brussel - Moorsel - Leuven 333 Leuven, Gasthuisberg – Rotselaar – Tremelo 334 Leuven -

Footloose in Flanders, Discovering One of the Seum That Is a Repository of Antwerp’S History but I Do Zip in Prettiest Regions of Europe in the Process

Travel BELGIUM Footloose in 1 2 Flanders A ROUND-UP OF THE FLEMISH TRIO OF BRUGES, GHENT AND ANTWERP. AND THEN AN OUTING TO BRUSSELS CHARUKESI R BY AMADURAI 3 4 f Eat, Pray, Love was a town, it would be Bruges. So pretty, so picture postcard that some guidebooks have described it as touristy and a tad fake. Our guide in Bruges splutters indig- nantly about the American who thought of it as a medieval Disneyland, asking him, “Is Bruges shut for winter?” Bruges is an-all weather destination, but to me, spring is the perfect time to be there. The tour- ist groups have just begun to trickle in, the daffodils are in full bloom at the charming Beguinage, FLANDERS where Benedictine nuns reside, and the weather makes me hum a happy tune all the time. FAIRYTALES: IAs I walk on the cobble-stoned lanes, I keep an ear open for the clip clop of horses ferrying tourists 1 The charm of across the UNESCO heritage town, the horseman (or in many cases, woman) doubling up as guide. Then, Bruges is in its canals there are the beguiling window displays on the chocolate shops lining the narrow shopping streets and lined by colourful the heady smell of Belgian frites (fries) in the air; together they erase all thoughts of calories and cho- buildings 2 Buskers lesterol from my mind. Remember, Eat is one of the leitmotifs for this town. are commonly found 5 To Pray, I head to the Church of Our Lady, to see Michelangelo’s sculpture of the Madonna and Child, in all Flanders cities in white Carrara marble. -

Infogids Geraardsbergen 2021-2022

www.geraardsbergen.be VOORWOORD/COLOFON INFOGIDS 2021-2022 Voorwoord Beste inwoner Je hebt de vernieuwde infogids ‘Wegwijs in Geraardsbergen 2021 – 2022’ in handen. Deze handige gids is opgebouwd uit twee delen. In een eerste deel wil het lokaal bestuur de stad een gezicht geven. Je vindt er een beknopte opsomming van de bestuurs- organen en hun leden met contactgegevens, en een overzicht van de gebouwen en diensten van de stad, de lokale politie en de brandweer. Het tweede deel bestaat uit een alfabetische trefwoordenlijst van alle aanbod van het lokaal bestuur, en de belangrijkste organisaties en instellingen in Geraardsbergen. Informatie is essentieel. Ondanks alle zorg die besteed werd aan het herwerken en vernieuwen van deze gids, kunnen bepaalde gegevens ontbreken of wijzigen. Merk je dit op, laat het dan weten aan de dienst Communicatie via [email protected] of 054 43 44 12/13. Op de website www.geraardsbergen.be vind je trouwens een digitale versie van deze gids, die steeds geüpdatet wordt met de laatste wijzigingen. Op deze website vind je verder ook de meest actuele nieuwsberichten en andere informatie terug, evenals het digitale Thuisloket. Dat zorgt er voor dat je op eender welk moment van steeds meer diensten gebruik kan maken. Voor de uitgave van deze gids was er opnieuw een samenwerking met heel wat lokale adverteerders. We willen hen bedanken: zij maken het mogelijk om je deze infogids gratis aan te bieden. We hopen dat deze gids zowel voor gevestigde Geraardsbergenaars als nieuwkomers een nuttige informatiebron zal zijn. Mocht je vragen of opmerkingen hebben, aarzel dan niet om ons te contacteren. -

Meerjarenplan 2014 – 2019 OCMW Geraardsbergen

Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Aalst Meerjarenplan 2014 – 2019 OCMW Geraardsbergen 1 Kattestraat 27 – 9500 GERAARDSBERGEN Tel. 054 43 20 00 [email protected] Belfius: 091-0009389-09 Code nummer 41018 2 Inhoud 1 Voorwoord van de ocmw-voorzitter .............................................................................................. 4 2 Meerjarenplan 2014 – 2019 OCMW Geraardsbergen .................................................................6 2.1 Strategische nota ..................................................................................................................... 6 2.1.1 Overzicht van de prioritaire beleidsdoelstellingen ..........................................................6 2.1.2 Strategische nota ................................................................................................................. 7 2.2 De financiële nota ................................................................................................................. 12 2.2.1 Het financiële doelstellingenplan – schema M1 .......................................................... 12 2.2.2 De staat van het financieel evenwicht - schema M2 ................................................. 13 2.3 Toelichting bij het meerjarenplan ....................................................................................... 15 2.3.1 Omgevingsanalyse ........................................................................................................... 15 2.3.2 Omschrijving van de financiële risico’s ......................................................................... -

State Forestry in Belgium Since the End of the Eighteenth Century

/ CHAPTER 3 State Forestry in Belgium since the End of the Eighteenth Century Pierre-Alain Tallier, Hilde Verboven, Kris Vandekerkhove, Hans Baeté and Kris Verheyen Forests are a key element in the structure of the landscape. Today they cover about 692,916 hectares, or about 22.7 per cent of Belgium. Unevenly distributed over the country, they constitute one of Belgium’s rare natural resources. For centuries, people have shaped these forests according to their needs and interests, resulting in the creation of man- aged forests with, to a greater or lesser extent, altered structure and species composition. Belgian forests have a long history in this respect. For millennia, they have served as a hideout, a place of worship, a food storage area and a material reserve for our ancestors. Our predecessors not only found part of their food supply in forests, but used the avail- able resources (herbs, leaves, brooms, heathers, beechnuts, acorns, etc.) to feed and to make their flocks of cows, goats and sheep prosper. Above all, forests have provided people with wood – a natural and renewable resource. As in many countries, depending on the available trees and technological evolutions, wood products have been used in various and multiple ways, such as heating and cooking (firewood, later on charcoal), making agricultural implements and fences (farmwood), and constructing and maintaining roads. Forests delivered huge quan- tities of wood for fortification, construction and furnishing, pit props, naval construction, coaches and carriages, and much more. Wood remained a basic material for industrial production up until the begin- ning of the nineteenth century, when it was increasingly replaced by iron, concrete, plastic and other synthetic materials. -

G-Sportbrochure Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen

G-SPORT in Oost-Vlaanderen SPORTAANBOD VOOR PERSONEN MET EEN BEPERKING 2020 MEER INFO? WWW.SPORT.VLAANDEREN Ook G-sporters beleven meer! Sport en beweging maakt gelukkig, verrijkt je vriendenkring en draagt bij aan je algemene gezondheid. Daarom willen wij zo veel mogelijk mensen in Vlaanderen en Brussel aanzetten tot regelmatig sporten en bewegen. Ben je op zoek naar een G-sportaanbod? In elke provincie en in het Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest is er een G-sportconsulent die het G-sportlandschap van de regio kent en je kan bijstaan in je zoektocht. Wil je graag zelf op zoek naar een sportclub die een G-sportaanbod heeft? Dan kan deze brochure jou hiermee helpen. In deze brochure kan je opzoeken welke (G-)sporten je in jouw buurt kan uitoefenen. Om een aanbod op maat te kunnen vinden, maakten we een onderscheid tussen verschillende doelgroepen en duidden we aan op welke manier G-sport zich situeert in de club. G-sport in de provincie Oost-Vlaanderen 3 Legende Leeftijd Alle leeftijden Ouder dan Sportclub G-sportclub: een sportclub die enkel een aanbod heeft voor personen met een beperking Sportclub met G-afdeling: een sportclub die G-sport aanbiedt naast het gewone sportaanbod Inclusieve sportclub: sporters met en zonder beperking sporten samen Doelgroepen Autismespectrumstoornis Doven en slechthorenden Fysieke beperking sport zonder rolstoel Fysieke beperking sport met rolstoel Psychische kwetsbaarheid Verstandelijke beperking Blinden en slechtzienden G-sport in de provincie Oost-Vlaanderen 5 G-sportaanbod w Atletiek DEINZE AC DEINZE Atletiekpiste -

Fresh Pigmeat and Certain Meat-Based Pork Products ;

21 . 8 . 87 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 238/31 COMMISSION DECISION of 28 July 1987 concerning certain protection measures relating to classical swine fever in Belgium (87/435/EEC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, HAS ADOPTED THIS DECISION : Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Article 1 Having regard to Council Directive 64/432/EEC of 26 June 1964 on animal health problems affecting intra The Kingdom of Belgium shall not send to other Community trade in bovine animals and swine ('), as last Member States live pigs coming from those parts of their amended by Directive 87/231 /EEC (2), and in particular territory described in the Annex . Article 9 thereof, Having regard to Council Directive 72/461 /EEC of 12 Article 2 December 1972 on health problems affecting intra Community trade in fresh meat (3), as last amended by 1 . The Kingdom of Belgium shall not send to other Directive 87/231 /EEC, and in particular Article 8 thereof, Member States fresh pigmeat coming from those part of their territory described in the Annex, and fresh pigmeat Whereas several outbreaks of classical swine fever have obtained from pigs coming from those parts of Belgium occurred in parts of Belgium outside the area where vacci but slaughtered elsewhere . nation is carried out on a routine basis ; 2 . The meat referred to in paragraph 1 shall bear either Whereas these outbreaks are liable to endanger the herds the national stamp or the stamp prescribed by Article 5a of other Member States, in view of the trade in live pigs, of Directive 72/461 /EEC . -

Sectorverdeling Planning En Kwaliteit Ouderenzorg Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen

Sectorverdeling planning en kwaliteit ouderenzorg provincie Oost-Vlaanderen Karolien Rottiers: arrondissementen Dendermonde - Eeklo Toon Haezaert: arrondissement Gent Karen Jutten: arrondissementen Sint-Niklaas - Aalst - Oudenaarde Gemeente Arrondissement Sectorverantwoordelijke Aalst Aalst Karen Jutten Aalter Gent Toon Haezaert Assenede Eeklo Karolien Rottiers Berlare Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers Beveren Sint-Niklaas Karen Jutten Brakel Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Buggenhout Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers De Pinte Gent Toon Haezaert Deinze Gent Toon Haezaert Denderleeuw Aalst Karen Jutten Dendermonde Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers Destelbergen Gent Toon Haezaert Eeklo Eeklo Karolien Rottiers Erpe-Mere Aalst Karen Jutten Evergem Gent Toon Haezaert Gavere Gent Toon Haezaert Gent Gent Toon Haezaert Geraardsbergen Aalst Karen Jutten Haaltert Aalst Karen Jutten Hamme Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers Herzele Aalst Karen Jutten Horebeke Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Kaprijke Eeklo Karolien Rottiers Kluisbergen Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Knesselare Gent Toon Haezaert Kruibeke Sint-Niklaas Karen Jutten Kruishoutem Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Laarne Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers Lebbeke Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers Lede Aalst Karen Jutten Lierde Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Lochristi Gent Toon Haezaert Lokeren Sint-Niklaas Karen Jutten Lovendegem Gent Toon Haezaert Maarkedal Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Maldegem Eeklo Karolien Rottiers Melle Gent Toon Haezaert Merelbeke Gent Toon Haezaert Moerbeke-Waas Gent Toon Haezaert Nazareth Gent Toon Haezaert Nevele Gent Toon Haezaert -

Brochure Bereikbaarheid

Brochure bereikbaarheid Regio Deinze maart 2018 Inhoud BEREIKBAARHEID VAN SCHOLEN “IDEAAL.” REGIO DEINZE .............................................. 3 1 ALGEMEEN ............................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Leiepoort campus Sint-Hendrik: Guido Gezellelaan 105. (A) .......................... 3 1.2. Leiepoort campus Sint-Vincentius: Peter Benoitlaan 40. (B) ........................... 3 1.3. Leiepoort campus Sint-Theresia: Gentpoortstraat 37. (C) .............................. 3 1.4. VTI Deinze: Leon Declercqstraat 1. (D) ........................................................... 3 2 MET DE FIETS ........................................................................................................... 4 3 MET DE LIJNBUS ...................................................................................................... 5 3.1. Overzichtskaart verbindingen Deinze ............................................................. 5 3.2. Lijst buslijnen in Deinze .................................................................................. 6 3.3. Haltes aan de scholen ..................................................................................... 6 3.4. Dienstregeling tijdens de schooluren ............................................................. 8 3.5. Buzzy pazz .................................................................................................... 22 3.6. Website De Lijn ........................................................................................... -

Appendix 1: Monastic and Religious Foundations in Thirteenth-Centur Y

APPENDIX 1: MONASTIC AND RELIGIOUS FOUNDATIONS IN THIRTEENTH-CENTURY FLANDERS AND HAINAUT Affiliation: Arrouaise Name Date of Foundation MenlWomen Eeckhout c. 1060/1146 Arrouaise Men Choques 1120/1138 Arrouaise Men Cysoing 855/1132 Arrouaise Men Phalernpin 1039/1145 Arrouaise Men Saint-Jean Baptiste c. 680/1142 Arrouaise Men Saint-Ni colas des Pres 1125/1140 Arrouaise Men Warneton 1066/1142 Arrouaise Men Zoetendale 1162/1215 re-founded Men Zonnebeke 1072/1142 Arrouaise Men Affiliation: Augustinian Canons Name Date of Foundation MenlWomen Saint-Aubert 963/1066 reforrned Men Saint-Marie, Voormezele 1069/1110 reforrned Men Saint-Martin, Ypres 1012/1102 reformed Men Saint-Pierre de Loo c. 1050/1093 reformed Men Saint-Pierre et Saint-Vaast c. 1091 Men Affiliation: Beguines Name Date cf Foundation MenlWomen Aardenburg 1249 Wornen Audenarde 1272 Wornen Bardonck, Y pres 1271/1273 Wornen Bergues 1259 Wornen 118 WOMEN, POWER, AND RELIGIOUS PATRONAGE Binehe 1248 Wornen Briel, Y pres 1240 Wornen Carnbrai 1233 Wornen Charnpfleury, Douai 1251 Wornen Damme 1259 Wornen Deinze 1273 Wornen Diksrnuide 1273 Wornen Ijzendijke 1276 Wornen Maubeuge 1273 Wornen Cantirnpre, Mons 1245 Wornen Orehies 1267 Wornen Portaaker (Ghent) 1273 Wornen Quesnoy 1246 Wornen Saint-Aubert (Bruges) 1270 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Courtrai) 1242 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Ghent) 1234 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Lilie) 1244/1245 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Valeneiennes) 1239 Wornen Ter Hooie (Ghent) 1262 Wornen Tournai 1241 Wornen Wetz (Douai) 1245 Wornen Wijngaard (Bruges) 1242 Wornen Affiliation: Benedictine Name Date oJ Foundation Men/Women Anehin 1079 Men Notre-Darne d'Avesnes 1028 Wornen Bergues Saint-Winoe 1028 Men Bourbourg c. 1099 Wornen Notre-Darne de Conde e. -

Belgium-Luxembourg-7-Preview.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Belgium & Luxembourg Bruges, Ghent & Antwerp & Northwest Belgium Northeast Belgium p83 p142 #_ Brussels p34 Wallonia p183 Luxembourg p243 #_ Mark Elliott, Catherine Le Nevez, Helena Smith, Regis St Louis, Benedict Walker PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to BRUSSELS . 34 ANTWERP Belgium & Luxembourg . 4 Sights . 38 & NORTHEAST Belgium & Luxembourg Tours . .. 60 BELGIUM . 142 Map . 6 Sleeping . 62 Antwerp (Antwerpen) . 144 Belgium & Luxembourg’s Eating . 65 Top 15 . 8 Around Antwerp . 164 Drinking & Nightlife . 71 Westmalle . 164 Need to Know . 16 Entertainment . 76 Turnhout . 165 First Time Shopping . 78 Lier . 167 Belgium & Luxembourg . .. 18 Information . 80 Mechelen . 168 If You Like . 20 Getting There & Away . 81 Leuven . 174 Getting Around . 81 Month by Month . 22 Hageland . 179 Itineraries . 26 Diest . 179 BRUGES, GHENT Hasselt . 179 Travel with Children . 29 & NORTHWEST Haspengouw . 180 Regions at a Glance . .. 31 BELGIUM . 83 Tienen . 180 Bruges . 85 Zoutleeuw . 180 Damme . 103 ALEKSEI VELIZHANIN / SHUTTERSTOCK © SHUTTERSTOCK / VELIZHANIN ALEKSEI Sint-Truiden . 180 Belgian Coast . 103 Tongeren . 181 Knokke-Heist . 103 De Haan . 105 Bredene . 106 WALLONIA . 183 Zeebrugge & Western Wallonia . 186 Lissewege . 106 Tournai . 186 Ostend (Oostende) . 106 Pipaix . 190 Nieuwpoort . 111 Aubechies . 190 Oostduinkerke . 111 Ath . 190 De Panne . 112 Lessines . 191 GALERIES ST-HUBERT, Beer Country . 113 Enghien . 191 BRUSSELS P38 Veurne . 113 Mons . 191 Diksmuide . 114 Binche . 195 MISTERVLAD / HUTTERSTOCK © HUTTERSTOCK / MISTERVLAD Poperinge . 114 Nivelles . 196 Ypres (Ieper) . 116 Waterloo Ypres Salient . 120 Battlefield . 197 Kortrijk . 123 Louvain-la-Neuve . 199 Oudenaarde . 125 Charleroi . 199 Geraardsbergen . 127 Thuin . 201 Ghent . 128 Aulne . 201 BRABO FOUNTAIN, ANTWERP P145 Contents UNDERSTAND Belgium & Luxembourg Today . -

Belgium-Luxembourg-6-Contents.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Belgium & Luxembourg Bruges & Antwerp & Western Flanders Eastern Flanders p83 p142 #_ Brussels p34 Western Wallonia p182 The Ardennes p203 Luxembourg p242 #_ THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Helena Smith, Andy Symington, Donna Wheeler PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Belgium BRUSSELS . 34 Antwerp to Ghent . 164 & Luxembourg . 4 Around Brussels . 81 Westmalle . 164 Belgium South of Brussels . 81 Hoogstraten . 164 & Luxembourg Map . 6 Southwest of Brussels . 82 Turnhout . 164 Belgium North of Brussels . 82 Lier . 166 & Luxembourg’s Top 15 . 8 Mechelen . 168 Need to Know . 16 BRUGES & WESTERN Leuven . 173 First Time . 18 FLANDERS . 83 Leuven to Hasselt . 177 Hasselt & Around . 178 If You Like . 20 Bruges (Brugge) . 85 Tienen . 178 Damme . 105 Month by Month . 22 Hoegaarden . 179 The Coast . 106 Zoutleeuw . 179 Itineraries . 26 Knokke-Heist . 107 Sint-Truiden . 180 Travel with Children . 29 Het Zwin . 107 Tongeren . 180 Regions at a Glance . .. 31 De Haan . 107 Zeebrugge . 108 Lissewege . 108 WESTERN Ostend (Oostende) . 108 WALLONIA . 182 MATT MUNRO /LONELY PLANET © PLANET /LONELY MUNRO MATT Nieuwpoort . 114 Tournai . 183 Oostduinkerke . 114 Pipaix . 188 St-Idesbald . 115 Aubechies . 189 De Panne & Adinkerke . 115 Belœil . 189 Veurne . 115 Lessines . 190 Diksmuide . 117 Enghien . 190 Beer Country . 117 Mons . 190 Westvleteren . 117 Waterloo Battlefield . 194 Woesten . 117 Nivelles . 196 Watou . 117 Louvain-la-Neuve . 197 CHOCOLATE LINE, BRUGES P103 Poperinge . 118 Villers-la-Ville . 197 Ypres (Ieper) . 119 Charleroi . 198 Ypres Salient . 123 Thuin . 199 HELEN CATHCART /LONELY PLANET © PLANET /LONELY HELEN CATHCART Comines . 124 Aulne . 199 Kortrijk . 125 Ragnies . 199 Oudenaarde .