Resurrecting the 'Spiritual Daughters': the Houtappel Chapel And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Footloose in Flanders, Discovering One of the Seum That Is a Repository of Antwerp’S History but I Do Zip in Prettiest Regions of Europe in the Process

Travel BELGIUM Footloose in 1 2 Flanders A ROUND-UP OF THE FLEMISH TRIO OF BRUGES, GHENT AND ANTWERP. AND THEN AN OUTING TO BRUSSELS CHARUKESI R BY AMADURAI 3 4 f Eat, Pray, Love was a town, it would be Bruges. So pretty, so picture postcard that some guidebooks have described it as touristy and a tad fake. Our guide in Bruges splutters indig- nantly about the American who thought of it as a medieval Disneyland, asking him, “Is Bruges shut for winter?” Bruges is an-all weather destination, but to me, spring is the perfect time to be there. The tour- ist groups have just begun to trickle in, the daffodils are in full bloom at the charming Beguinage, FLANDERS where Benedictine nuns reside, and the weather makes me hum a happy tune all the time. FAIRYTALES: IAs I walk on the cobble-stoned lanes, I keep an ear open for the clip clop of horses ferrying tourists 1 The charm of across the UNESCO heritage town, the horseman (or in many cases, woman) doubling up as guide. Then, Bruges is in its canals there are the beguiling window displays on the chocolate shops lining the narrow shopping streets and lined by colourful the heady smell of Belgian frites (fries) in the air; together they erase all thoughts of calories and cho- buildings 2 Buskers lesterol from my mind. Remember, Eat is one of the leitmotifs for this town. are commonly found 5 To Pray, I head to the Church of Our Lady, to see Michelangelo’s sculpture of the Madonna and Child, in all Flanders cities in white Carrara marble. -

Appendix 1: Monastic and Religious Foundations in Thirteenth-Centur Y

APPENDIX 1: MONASTIC AND RELIGIOUS FOUNDATIONS IN THIRTEENTH-CENTURY FLANDERS AND HAINAUT Affiliation: Arrouaise Name Date of Foundation MenlWomen Eeckhout c. 1060/1146 Arrouaise Men Choques 1120/1138 Arrouaise Men Cysoing 855/1132 Arrouaise Men Phalernpin 1039/1145 Arrouaise Men Saint-Jean Baptiste c. 680/1142 Arrouaise Men Saint-Ni colas des Pres 1125/1140 Arrouaise Men Warneton 1066/1142 Arrouaise Men Zoetendale 1162/1215 re-founded Men Zonnebeke 1072/1142 Arrouaise Men Affiliation: Augustinian Canons Name Date of Foundation MenlWomen Saint-Aubert 963/1066 reforrned Men Saint-Marie, Voormezele 1069/1110 reforrned Men Saint-Martin, Ypres 1012/1102 reformed Men Saint-Pierre de Loo c. 1050/1093 reformed Men Saint-Pierre et Saint-Vaast c. 1091 Men Affiliation: Beguines Name Date cf Foundation MenlWomen Aardenburg 1249 Wornen Audenarde 1272 Wornen Bardonck, Y pres 1271/1273 Wornen Bergues 1259 Wornen 118 WOMEN, POWER, AND RELIGIOUS PATRONAGE Binehe 1248 Wornen Briel, Y pres 1240 Wornen Carnbrai 1233 Wornen Charnpfleury, Douai 1251 Wornen Damme 1259 Wornen Deinze 1273 Wornen Diksrnuide 1273 Wornen Ijzendijke 1276 Wornen Maubeuge 1273 Wornen Cantirnpre, Mons 1245 Wornen Orehies 1267 Wornen Portaaker (Ghent) 1273 Wornen Quesnoy 1246 Wornen Saint-Aubert (Bruges) 1270 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Courtrai) 1242 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Ghent) 1234 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Lilie) 1244/1245 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Valeneiennes) 1239 Wornen Ter Hooie (Ghent) 1262 Wornen Tournai 1241 Wornen Wetz (Douai) 1245 Wornen Wijngaard (Bruges) 1242 Wornen Affiliation: Benedictine Name Date oJ Foundation Men/Women Anehin 1079 Men Notre-Darne d'Avesnes 1028 Wornen Bergues Saint-Winoe 1028 Men Bourbourg c. 1099 Wornen Notre-Darne de Conde e. -

Ryan D. Giles 34 ISSN 1540 5877 Ehumanista 32 (2016): 34-49 “Mira

Ryan D. Giles 34 “Mira mis llagas”: Heridas divinas en las obras de Brígida de Suecia y Teresa de Jesús Ryan D. Giles (Indiana University) En 1559 Teresa de Ávila tuvo su experiencia mística más célebre, conocida como la transverberación, cuando sintió el corazón traspasado por una fuerza sobrenatural. En su autobiografía, Teresa primero recuerda cómo Cristo se le aparecía, con la corona de espinas, crucificado, mostrándole sus heridas y en ocasiones cargando la cruz. Anteriormente, uno de sus confesores le había instado a protegerse de estas apariciones con “las higas,” un gesto para evitar que el demonio la llevara en camino de perdición e ilusorio (Vida 29.5). Algún tiempo después, la monja tuvo otra visión similar, solo que en esa ocasión Cristo aparece en la cruz del rosario de la santa, y le muestra las cinco heridas sufridas durante la Pasión. Este capítulo de su Vida culmina con la aparición de un ángel que sostiene un “dardo de oro” con la punta de hierro encendida en llamas, con la cual hiere la carne de Teresa y penetra su corazón (29.13). La transverberación conlleva también un dolor agudo, seguido de un dulce éxtasis libre de sufrimiento corporal y tan espiritualmente fecundo que Teresa manifiesta desear que dicha experiencia dure para siempre. Además de este episodio tan conocido, en las obras de la santa abundan descripciones del alma herida, tanto como representaciones y contemplaciones de las llagas de Cristo experimentadas a través de las artes visuales, visiones y reflexiones en prosa y poesía. Historiadores del misticismo han identificado un proceso de transición en las experiencias de visionarias a finales de la Edad Media. -

From Historic Centre to Design City on the Water CITY on the WATER

2016 2017 CAPTIVATING KORTRIJK from historic centre to design city on the water CITY ON THE WATER The banks of the Leie and the course of the Old Leie are the place to be! The green zone is ideal for young and old to enjoy some undisturbed peace. And in the middle of a city! The banks bring you wonderfully close to the fresh water and the moored pleasure craft, so that you can sit on one of the delightful terraces and almost feel the water. After the Middle Ages, the River Leie, and the linen and damask industry that grew up around it, played the leading role. Successfully too! From the 18th century Kortrijk enjoyed fame as the world centre for fl ax. Thanks to the creative entrepreneurship of its people, Kortrijk grew to become the vibrant, economic heart of the region. A new Leie needs new bridges. Seven impressive examples redraw the Kortrijk skyline and aff ord it a distinctive, imposing appearance. No boring or identical copies, but seven distinctive bridges that will help both visitors and locals orientate themselves. Sometimes majestic big city structures, at other times bold zigzags. 2 CITY ON THE WATER King Albertpark and skatebowl Texture, museum of Flax and river Lys Recently King Leopold III and his horse gaze over an open park Texture tells the rich story of fl ax in three totally diff erent and the renewed Leie banks. Th e park, which is bordered by rooms. You start in the Wonder Room: a fun laboratory about the lowered river banks, forms the transition between the city fl ax in your everyday life. -

Jose Toribio Medina Collection of Latin American Imprints, 1500-1800 Author Index

Latin American History and Culture: Series 6: Parts 1-7: Jose Toribio Medina Collection of Latin American Imprints, 1500-1800 Author Index Abad Illana, Manuel, 1713-1780. Abarca y Valda, José Mariano de, b. 1720. Carta pastoral [microform] / del ilvstrisimo señor d. don Loa, y explicacion del arco, [Microform] que la santa Manvel Abad Yllana ; del consejo de Sv Magestad obispo de Iglesia metropolitana de Mexico, para desempeño de su amor, Areqvipa &c. : la que escribio con ocasion del jubiléo del año erigiò en la entrada que hizo a su govierno el excelentissimo santo, concedido por nuestro santisimo padre Pio VI, y para señor don Augustin de Ahumada, y Villalon, marquès de las publicarle en la capital de su diocesí [sic] à 16 marzo, del año Amarillas ... Escribiola don Joseph Mariano de Abarca, Valda, de 1777. y Velasquez ... Lima : [s.n.], 1777. 1777 [Mexico] Con licencia en la imprenta nueva de la Bibliotheca mexicana, enfrente de San Augustin. Año 1756. 1756 Abad y Aramburu, Julián. Oracion funebre [icroform] : que en el sufragio solemne Abarca y Valda, José Mariano de, b. 1720. que ofrecieron por la alma de el señor don Josef Escandon y Ojo politico, idea cabal, y ajustada copia de principes, Helguera, conde de la Sierra Gorda ... sus hijos don Manuel [Microform] que diò a luz la santa Iglesia metropolitana de Escandon y Llera, conde de la Sierra Gorda, el br. d. Mariano Mexico, en el Magnifico arco, que dedicò amorosa en la Escandon y Llera, d. Francisco Escandon y Llera, d. Melchor entrada que hizo a su govierno el excelentissimo señor don de Noriega, y d. -

The Beguine Option: a Persistent Past and a Promising Future of Christian Monasticism

religions Article The Beguine Option: A Persistent Past and a Promising Future of Christian Monasticism Evan B. Howard Department of Ministry, Fuller Theological Seminary 62421 Rabbit Trail, Montrose, CO 81403, USA; [email protected] Received: 1 June 2019; Accepted: 3 August 2019; Published: 21 August 2019 Abstract: Since Herbert Grundmann’s 1935 Religious Movements in the Middle Ages, interest in the Beguines has grown significantly. Yet we have struggled whether to call Beguines “religious” or not. My conviction is that the Beguines are one manifestation of an impulse found throughout Christian history to live a form of life that resembles Christian monasticism without founding institutions of religious life. It is this range of less institutional yet seriously committed forms of life that I am here calling the “Beguine Option.” In my essay, I will sketch this “Beguine Option” in its varied expressions through Christian history. Having presented something of the persistent past of the Beguine Option, I will then present an introduction to forms of life exhibited in many of the expressions of what some have called “new monasticism” today, highlighting the similarities between movements in the past and new monastic movements in the present. Finally, I will suggest that the Christian Church would do well to foster the development of such communities in the future as I believe these forms of life hold much promise for manifesting and advancing the kingdom of God in our midst in a postmodern world. Keywords: monasticism; Beguine; spiritual formation; intentional community; spirituality; religious life 1. Introduction What might the future of monasticism look like? I start with three examples: two from the present and one from the past. -

The Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture THE CRISTOS YACENTES OF GREGORIO FERNÁNDEZ: POLYCHROME SCULPTURES OF THE SUPINE CHRIST IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY SPAIN A Dissertation in Art History by Ilenia Colón Mendoza © 2008 Ilenia Colón Mendoza Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2008 The dissertation of Ilenia Colón Mendoza was reviewed and approved* by the following: Jeanne Chenault Porter Associate Professor Emeritus of Art History Dissertation Co-Advisor Co-Chair of Committee Brian A. Curran Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Co-Advisor Co-Chair of Committee Elizabeth J. Walters Associate Professor of Art History Simone Osthoff Associate Professor of Art Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract The Cristo yacente, or supine Christ, is a sculptural type whose origins date back to the Middle Ages. In seventeenth-century Spain these images became immensely popular as devotional aids and vehicles for spiritual contemplation. As a form of sacred drama these sculptures encouraged the faithful to reflect upon the suffering, death, and Resurrection of Christ as well as His promise of salvation. Perhaps the most well-known example of this type is by the Valladolidian sculptor, Gregorio Fernández (1576-1636). Located in the Capuchin Convent of El Pardo near Madrid, this work was created in accordance with Counter-Reformation mandates that required religious images inspire both piety and empathy. As a “semi-narrative”, the Cristo yacente encompasses different moments in the Passion of Christ, including the Lamentation, Anointment, and Entombment. -

Sales Guide 2019 English Version © M

EN Sales Guide 2019 English version © M. Vanhulst The visit.brussels online sales guide is accessible to all, but is first and foremost aimed at professionals from the travel industry, namely tour operators, travel agents, coach companies and group organisers. It provides a complete overview of all activities and attractions in our city. These are then divided into specific themes which best represent Brussels, e.g. Art Nouveau, comics, heritage, etc. Each activity or attraction is explained in a file containing valuable information such as rates, contact details, languages in which the activity or attraction is provided, and much more. These files will allow travel professionals to take immediate action, should they wish to suggest an activity or attraction to their clients. The entire purpose of the sales guide is to advertise the tremendous potential of Brussels and boost creativity with travel professionals in order for them to perk up, enhance or change their offer whilst making them and their clients eager to discover and get a better idea of the city. Equally important, the sales guide limits research and hence lightens the workload considerably. In addition, the visit.brussels online sales guide obviously contains information on upcoming events, accommodation providers, coach parking details, visit.brussels contact information and other relevant data. We trust this unique tool will benefit all travel professionals worldwide and encourage them to choose Brussels as their preferred destination. Rest assured that we will keep on -

Welcome to the World Heritage City of Bruges

Welcome to the World Heritage City of Bruges There are places that somehow manage tant events and a complete summary of to get under your skin, even though you the Bruges museums, attractions and don’t really know them all that well. other sites of interest, including histor- Bruges is that kind of place. A warm and ical, cultural and religious buildings friendly place, a place made for people. and locations. Bruges’ beautiful A city whose history made it great, re- squares and enchanting canals are the sulting in a well-deserved classification regular backdrop for topclass cultural as a Unesco World Heritage site. events. And few cities have such a rich and diverse variety of museums, which 1 In this guide you will discover Bruges’ contain gems ranging from the Flemish FOREWORD different facets. There are five separate primitives and beautiful lace work to chapters. the finest modern art of today. In chapter 1 you will find everything you In Bruges you can dine at a different need to prepare your trip to Bruges. You star-rated restaurant each day, or per- will read about the ten must sees, get a haps you would prefer lunch at a trendy brief summary of the city’s history and bistro before wandering through the discover lots of practical information. winding cobbled streets of the city? Or Further in this chapter, the lovers of good maybe you just want to take in a pleasant food and drink will find a list of the best pub or one of the many magnificent ter- restaurants, while the shopaholics will races with a view? These are the places, receive tips for the most authentic and full of charm and character, which you top-quality shopping addresses. -

World Heritage City

BRUGES WORLD HERITAGE CITY 1 INTRODUCTION ruges is a unique city and is featured in the list of World Heritage Sites no less than four times. The historic centre of Bruges was acknowledged as a World Heritage Site on November 30th 2000. The Beguinage and the Belfry had already been included in the list in 1998 and 1999 respectively. In 2009 the Procession of the Holy Blood was recognized as Immaterial World Heritage. The title of World Heritage Site is a prestigious one. It puts the city on the international map and therefore holds additional cultural and tourist appeal. The city owes a lot to its past and its unique historical position. A city connected with the hanseatic league and the centre of European trade in the Middle Ages, Bruges is a compact city, densely built and with a wealth of art treasures. The unique architectural heritage has been carefully preserved throughout the centuries. In addition, Bruges boasts impressive museum collections, the most important of which is the collection of Flemish Primitives. Other treasures have been preserved in museums, churches, archives, foundations and the Municipal Public Library. The city also has a lot to offer in the field of immaterial heritage: the Procession of the Holy Blood recognised by Uneso, the Our Lady of Blindekens procession, the archers guilds, the musical traditions, to name only a few. This makes Bruges a paradise for those looking for additional value. The recognition as World Heritage is largely due to the architectural heritage, in particular because the city of Bruges is regarded as a ’textbook’ of architectural history, specifically of ‘Brick Gothic’. -

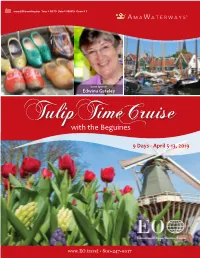

With the Beguines

www.EO.travel/mytrip Tour = RC19 Date = 040518 Code = T Guest Speaker Edwina Gateley TulipwithTime the BeguinesCruise 9 Days - April 5-13, 2019 www.EO.travel • 800-247-0017 - Roundtrip Amsterdam - April 5 – Depart USA learn about the beguinage’s unique history through their unique Board your overnight flight to Amsterdam. media displays. The very last beguine in the world, Marcella Pattyn, April 6 – ARRIVE IN AMSTERDAM, THE NETHERLANDS – resided in this beguinage from 1960-2005. (B,L,D) EMBARKATION - EO Exclusive Excursion April 10 – ANTWERP - EO Exclusive Excursion Welcome to Amsterdam. Visit the Beginhof (Begiunage of Explore this trendy city on a walking tour where you’ll see Antwerp’s Amsterdam) and see Amsterdam’s oldest preserved wooden house Steen Castle, Grote Market and Brabo Fountain, along with the built in 1465. Visit the Beginhof Kapel (Beguinage Chapel) built in UNESCO-designated Cathedral of Our Lady, where you can marvel at 1671 as a secret chapel for Catholics to worship in during Calvinist the works of the artist, Peter Paul Rubens. Next visit the Beguinage of rule. Transfer to the port to board your luxurious river cruise ship. Antwerp, built in 1545. The last Antwerp Beguine, Virginia Laeremans This evening, meet your fellow travelers on board at the Welcome lived here until her death in 1986. This is now a modern residential Dinner. (D) area but they have kept the original character of the 40 remaining April 7 – AMSTERDAM – HOORN houses, the tranquility of its 16th century garden and the name of Enjoy a scenic cruise through the Ijsselmeer to Hoorn, where you Saint Helige Martha on its gate preserved. -

World's Columbian Exposition, 1893 : Official Catalogue. Part X

> * * ■ . * * • / Official Catalogue /» OF EXHIBITS^ W ORIsD’S COLUMBIAN Exposition Department K. FlNB f\RTS» Chicago W. B. GONKEY COMPANY, PUBLISHERS TO THE EXPOSITION (A 1893 606 9 4 * f , i World’s Columbian Exposition 1893 ♦ OFFICIAL CATALOGUE Pf\RT X. ART GALLERIES and ANNEXES Department K. FINE ARTS Painting, Sculpture, Architecture,, DE.GORATION HALSEY G. IV&S, Chief » —— . .. • • • - ^ Edited by The Department of Publicity and Promotion M. P. HANDY, Chief CHICAGO: W. B. CONKEY COMPANY, PUBLISHERS TO THE World's Columbian exposition, 1693. 4 Entered according to Act of Congress in the year A. D. 1893, in the office of Librarian of Congress at Washington, D. C., by The World’s Columbian Exposition, For the exclusive use of W. B. Conkey Company, Chicago. This Catalogue presents the lists of exhibitors and exhibits as they were installed or accepted for installation, according to information filed with the editor of the Catalogue at the time of going to press. Additional entries, withdrawals, or changes in location of exhibits, will be noted in a subsequent edition. W. B. CONKEY COMPANY PRINTERS AND BINDERS CHICAGO. DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS. (K> HALSEY C. IVES, CHIEF. CHARLES M. KURTZ, ASSISTANT CHIEF. SARA T. HALLOWELL, ASSISTANT. LOUIS J. MILLET, SUPERINTENDENT OF ARCHITECTURAL AND DECORATIVE EXHIBITS GEORGE CORLISS, SUPERINTENDENT OF GALLERIES. I 6 DEPARTMENT K.—FINE ARTS. GROUP 143.—ENGRAVINGS AND ETCHINGS; PRINTS. FOR ETCHINGS NEW YORK. Carleton T. Chapman. C. F. W. Mielatz. Samuel Colman. C. A. Platt. James D. Smillie. PHILADELPHIA. Hermann Faber. Max Rosenthal. Bernhard Uhle. BOSTON. W. B. Closson. S. R. Koehler. Charles A.