The Persistent Effect of Beguinages on Attitudes Toward Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overzicht Hinder Voor Dienstverlening

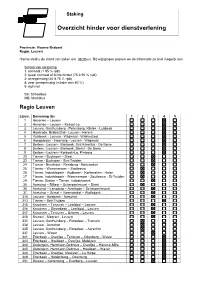

Staking Overzicht hinder voor dienstverlening Provincie: Vlaams-Brabant Regio: Leuven Hierna vindt u de stand van zaken om 06.00uur. Bij wijzigingen passen we de informatie zo snel mogelijk aan. Schaal van verstoring 1: normaal (+ 95 % rijdt) 2: quasi normaal of lichte hinder (75 à 95 % rijdt) 3: onregelmatig (40 à 75 % rijdt) 4: zeer onregelmatig (minder dan 40 %) 5: rijdt niet SB: Schoolbus MB: Marktbus Regio Leuven Lijnnr. Benaming lijn 1 2 3 4 5 1 Heverlee – Leuven 2 Heverlee – Leuven – Kessel-Lo 3 Leuven, Gasthuisberg - Pellenberg, Kliniek - Lubbeek 4 Haasrode, Brabanthal - Leuven - Herent 5 Vaalbeek - Leuven - Wijgmaal - Wakkerzeel 6 Hoegaarden - Neervelp - Leuven - Wijgmaal 7 Bertem - Leuven - Bierbeek, Sint-Kamillus - De Borre 8 Bertem - Leuven - Bierbeek, Bremt - De Borre 9 Bertem - Leuven - Korbeek-Lo, Pimberg 22 Tienen – Budingen – Diest 23 Tienen - Budingen - Sint-Truiden 24 Tienen - Neerlinter - Ransberg - Kortenaken 25 Tienen – Wommersom – Zoutleeuw 26 Tienen, Industriepark - Budingen - Kortenaken - Halen 27 Tienen, Industriepark - Wommersom - Zoutleeuw - St-Truiden 29 Tienen, Station – Tienen, Industriepark 35 Aarschot – Rillaar – Scherpenheuvel – Diest 36 Aarschot – Langdorp – Averbode – Scherpenheuvel 37 Aarschot – Gijmel – Varenwinkel – Wolfsdonk 310 Leuven - Holsbeek - Aarschot 313 Tienen – Sint-Truiden 315 Kraainem – Tervuren – Leefdaal – Leuven 316 Kraainem – Sterrebeek – Leefdaal – Leuven 317 Kraainem – Tervuren – Bertem – Leuven 318 Brussel - Moorsel - Leuven 333 Leuven, Gasthuisberg – Rotselaar – Tremelo 334 Leuven -

Footloose in Flanders, Discovering One of the Seum That Is a Repository of Antwerp’S History but I Do Zip in Prettiest Regions of Europe in the Process

Travel BELGIUM Footloose in 1 2 Flanders A ROUND-UP OF THE FLEMISH TRIO OF BRUGES, GHENT AND ANTWERP. AND THEN AN OUTING TO BRUSSELS CHARUKESI R BY AMADURAI 3 4 f Eat, Pray, Love was a town, it would be Bruges. So pretty, so picture postcard that some guidebooks have described it as touristy and a tad fake. Our guide in Bruges splutters indig- nantly about the American who thought of it as a medieval Disneyland, asking him, “Is Bruges shut for winter?” Bruges is an-all weather destination, but to me, spring is the perfect time to be there. The tour- ist groups have just begun to trickle in, the daffodils are in full bloom at the charming Beguinage, FLANDERS where Benedictine nuns reside, and the weather makes me hum a happy tune all the time. FAIRYTALES: IAs I walk on the cobble-stoned lanes, I keep an ear open for the clip clop of horses ferrying tourists 1 The charm of across the UNESCO heritage town, the horseman (or in many cases, woman) doubling up as guide. Then, Bruges is in its canals there are the beguiling window displays on the chocolate shops lining the narrow shopping streets and lined by colourful the heady smell of Belgian frites (fries) in the air; together they erase all thoughts of calories and cho- buildings 2 Buskers lesterol from my mind. Remember, Eat is one of the leitmotifs for this town. are commonly found 5 To Pray, I head to the Church of Our Lady, to see Michelangelo’s sculpture of the Madonna and Child, in all Flanders cities in white Carrara marble. -

Fresh Pigmeat and Certain Meat-Based Pork Products ;

21 . 8 . 87 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 238/31 COMMISSION DECISION of 28 July 1987 concerning certain protection measures relating to classical swine fever in Belgium (87/435/EEC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, HAS ADOPTED THIS DECISION : Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Article 1 Having regard to Council Directive 64/432/EEC of 26 June 1964 on animal health problems affecting intra The Kingdom of Belgium shall not send to other Community trade in bovine animals and swine ('), as last Member States live pigs coming from those parts of their amended by Directive 87/231 /EEC (2), and in particular territory described in the Annex . Article 9 thereof, Having regard to Council Directive 72/461 /EEC of 12 Article 2 December 1972 on health problems affecting intra Community trade in fresh meat (3), as last amended by 1 . The Kingdom of Belgium shall not send to other Directive 87/231 /EEC, and in particular Article 8 thereof, Member States fresh pigmeat coming from those part of their territory described in the Annex, and fresh pigmeat Whereas several outbreaks of classical swine fever have obtained from pigs coming from those parts of Belgium occurred in parts of Belgium outside the area where vacci but slaughtered elsewhere . nation is carried out on a routine basis ; 2 . The meat referred to in paragraph 1 shall bear either Whereas these outbreaks are liable to endanger the herds the national stamp or the stamp prescribed by Article 5a of other Member States, in view of the trade in live pigs, of Directive 72/461 /EEC . -

Appendix 1: Monastic and Religious Foundations in Thirteenth-Centur Y

APPENDIX 1: MONASTIC AND RELIGIOUS FOUNDATIONS IN THIRTEENTH-CENTURY FLANDERS AND HAINAUT Affiliation: Arrouaise Name Date of Foundation MenlWomen Eeckhout c. 1060/1146 Arrouaise Men Choques 1120/1138 Arrouaise Men Cysoing 855/1132 Arrouaise Men Phalernpin 1039/1145 Arrouaise Men Saint-Jean Baptiste c. 680/1142 Arrouaise Men Saint-Ni colas des Pres 1125/1140 Arrouaise Men Warneton 1066/1142 Arrouaise Men Zoetendale 1162/1215 re-founded Men Zonnebeke 1072/1142 Arrouaise Men Affiliation: Augustinian Canons Name Date of Foundation MenlWomen Saint-Aubert 963/1066 reforrned Men Saint-Marie, Voormezele 1069/1110 reforrned Men Saint-Martin, Ypres 1012/1102 reformed Men Saint-Pierre de Loo c. 1050/1093 reformed Men Saint-Pierre et Saint-Vaast c. 1091 Men Affiliation: Beguines Name Date cf Foundation MenlWomen Aardenburg 1249 Wornen Audenarde 1272 Wornen Bardonck, Y pres 1271/1273 Wornen Bergues 1259 Wornen 118 WOMEN, POWER, AND RELIGIOUS PATRONAGE Binehe 1248 Wornen Briel, Y pres 1240 Wornen Carnbrai 1233 Wornen Charnpfleury, Douai 1251 Wornen Damme 1259 Wornen Deinze 1273 Wornen Diksrnuide 1273 Wornen Ijzendijke 1276 Wornen Maubeuge 1273 Wornen Cantirnpre, Mons 1245 Wornen Orehies 1267 Wornen Portaaker (Ghent) 1273 Wornen Quesnoy 1246 Wornen Saint-Aubert (Bruges) 1270 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Courtrai) 1242 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Ghent) 1234 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Lilie) 1244/1245 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Valeneiennes) 1239 Wornen Ter Hooie (Ghent) 1262 Wornen Tournai 1241 Wornen Wetz (Douai) 1245 Wornen Wijngaard (Bruges) 1242 Wornen Affiliation: Benedictine Name Date oJ Foundation Men/Women Anehin 1079 Men Notre-Darne d'Avesnes 1028 Wornen Bergues Saint-Winoe 1028 Men Bourbourg c. 1099 Wornen Notre-Darne de Conde e. -

Belgium-Luxembourg-7-Preview.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Belgium & Luxembourg Bruges, Ghent & Antwerp & Northwest Belgium Northeast Belgium p83 p142 #_ Brussels p34 Wallonia p183 Luxembourg p243 #_ Mark Elliott, Catherine Le Nevez, Helena Smith, Regis St Louis, Benedict Walker PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to BRUSSELS . 34 ANTWERP Belgium & Luxembourg . 4 Sights . 38 & NORTHEAST Belgium & Luxembourg Tours . .. 60 BELGIUM . 142 Map . 6 Sleeping . 62 Antwerp (Antwerpen) . 144 Belgium & Luxembourg’s Eating . 65 Top 15 . 8 Around Antwerp . 164 Drinking & Nightlife . 71 Westmalle . 164 Need to Know . 16 Entertainment . 76 Turnhout . 165 First Time Shopping . 78 Lier . 167 Belgium & Luxembourg . .. 18 Information . 80 Mechelen . 168 If You Like . 20 Getting There & Away . 81 Leuven . 174 Getting Around . 81 Month by Month . 22 Hageland . 179 Itineraries . 26 Diest . 179 BRUGES, GHENT Hasselt . 179 Travel with Children . 29 & NORTHWEST Haspengouw . 180 Regions at a Glance . .. 31 BELGIUM . 83 Tienen . 180 Bruges . 85 Zoutleeuw . 180 Damme . 103 ALEKSEI VELIZHANIN / SHUTTERSTOCK © SHUTTERSTOCK / VELIZHANIN ALEKSEI Sint-Truiden . 180 Belgian Coast . 103 Tongeren . 181 Knokke-Heist . 103 De Haan . 105 Bredene . 106 WALLONIA . 183 Zeebrugge & Western Wallonia . 186 Lissewege . 106 Tournai . 186 Ostend (Oostende) . 106 Pipaix . 190 Nieuwpoort . 111 Aubechies . 190 Oostduinkerke . 111 Ath . 190 De Panne . 112 Lessines . 191 GALERIES ST-HUBERT, Beer Country . 113 Enghien . 191 BRUSSELS P38 Veurne . 113 Mons . 191 Diksmuide . 114 Binche . 195 MISTERVLAD / HUTTERSTOCK © HUTTERSTOCK / MISTERVLAD Poperinge . 114 Nivelles . 196 Ypres (Ieper) . 116 Waterloo Ypres Salient . 120 Battlefield . 197 Kortrijk . 123 Louvain-la-Neuve . 199 Oudenaarde . 125 Charleroi . 199 Geraardsbergen . 127 Thuin . 201 Ghent . 128 Aulne . 201 BRABO FOUNTAIN, ANTWERP P145 Contents UNDERSTAND Belgium & Luxembourg Today . -

Belgium-Luxembourg-6-Contents.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Belgium & Luxembourg Bruges & Antwerp & Western Flanders Eastern Flanders p83 p142 #_ Brussels p34 Western Wallonia p182 The Ardennes p203 Luxembourg p242 #_ THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Helena Smith, Andy Symington, Donna Wheeler PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Belgium BRUSSELS . 34 Antwerp to Ghent . 164 & Luxembourg . 4 Around Brussels . 81 Westmalle . 164 Belgium South of Brussels . 81 Hoogstraten . 164 & Luxembourg Map . 6 Southwest of Brussels . 82 Turnhout . 164 Belgium North of Brussels . 82 Lier . 166 & Luxembourg’s Top 15 . 8 Mechelen . 168 Need to Know . 16 BRUGES & WESTERN Leuven . 173 First Time . 18 FLANDERS . 83 Leuven to Hasselt . 177 Hasselt & Around . 178 If You Like . 20 Bruges (Brugge) . 85 Tienen . 178 Damme . 105 Month by Month . 22 Hoegaarden . 179 The Coast . 106 Zoutleeuw . 179 Itineraries . 26 Knokke-Heist . 107 Sint-Truiden . 180 Travel with Children . 29 Het Zwin . 107 Tongeren . 180 Regions at a Glance . .. 31 De Haan . 107 Zeebrugge . 108 Lissewege . 108 WESTERN Ostend (Oostende) . 108 WALLONIA . 182 MATT MUNRO /LONELY PLANET © PLANET /LONELY MUNRO MATT Nieuwpoort . 114 Tournai . 183 Oostduinkerke . 114 Pipaix . 188 St-Idesbald . 115 Aubechies . 189 De Panne & Adinkerke . 115 Belœil . 189 Veurne . 115 Lessines . 190 Diksmuide . 117 Enghien . 190 Beer Country . 117 Mons . 190 Westvleteren . 117 Waterloo Battlefield . 194 Woesten . 117 Nivelles . 196 Watou . 117 Louvain-la-Neuve . 197 CHOCOLATE LINE, BRUGES P103 Poperinge . 118 Villers-la-Ville . 197 Ypres (Ieper) . 119 Charleroi . 198 Ypres Salient . 123 Thuin . 199 HELEN CATHCART /LONELY PLANET © PLANET /LONELY HELEN CATHCART Comines . 124 Aulne . 199 Kortrijk . 125 Ragnies . 199 Oudenaarde . -

Lijst Erkende Inrichtingen Afdeling 0

Lijst erkende inrichtingen 1/09/21 Afdeling 0: Inrichting algemene activiteiten Erkenningnr. Benaming Adres Categorie Neven activiteit Diersoort Opmerkingen KF1 Amnimeat B.V.B.A. Rue Ropsy Chaudron 24 b 5 CS CP, PP 1070 Anderlecht KF10 Eurofrost NV Izegemsestraat(Heu) 412 CS 8501 Heule KF100 BARIAS Ter Biest 15 CS FFPP, PP 8800 Roeselare KF1001 Calibra Moorseelsesteenweg 228 CS CP, MP, MSM 8800 Roeselare KF100104 LA MAREE HAUTE Quai de Mariemont 38 CS 1080 Molenbeek-Saint-Jean KF100109 maatWERKbedrijf BWB Nijverheidsstraat 15 b 2 CS RW 1840 Londerzeel KF100109 maatWERKbedrijf BWB Nijverheidsstraat 15 b 2 RW CS 1840 Londerzeel KF100159 LA BOUCHERIE SA Rue Bollinckx 45 CS CP, MP, PP 1070 Anderlecht KF100210 H.G.C.-HANOS Herkenrodesingel 81 CS CC, PP, CP, FFPP, MP 3500 Hasselt KF100210 Van der Zee België BVBA Herkenrodesingel 81 CS CP, MP 3500 Hasselt KF100227 CARDON LOGISTIQUE Rue du Mont des Carliers(BL) S/N CS 7522 Tournai KF100350 HUIS PATRICK Ambachtenstraat(LUB) 7 CS FFPP, RW 3210 Lubbeek KF100350 HUIS PATRICK Ambachtenstraat(LUB) 7 RW CS, FFPP 3210 Lubbeek KF100378 Lineage Ieper BVBA Bargiestraat 5 CS 8900 Ieper KF100398 BOURGONJON Nijverheidskaai 18 b B CS CP, MP, RW 9040 Gent KF100398 BOURGONJON Nijverheidskaai 18 b B RW CP, CS, MP 9040 Gent KF1004 PLUKON MOUSCRON Avenue de l'Eau Vive(L) 5 CS CP, SH 7700 Mouscron/Moeskroen 1 / 196 Lijst erkende inrichtingen 1/09/21 Afdeling 0: Inrichting algemene activiteiten Erkenningnr. Benaming Adres Categorie Neven activiteit Diersoort Opmerkingen KF100590 D.S. PRODUKTEN Hoeikensstraat 5 b 107 -

From Historic Centre to Design City on the Water CITY on the WATER

2016 2017 CAPTIVATING KORTRIJK from historic centre to design city on the water CITY ON THE WATER The banks of the Leie and the course of the Old Leie are the place to be! The green zone is ideal for young and old to enjoy some undisturbed peace. And in the middle of a city! The banks bring you wonderfully close to the fresh water and the moored pleasure craft, so that you can sit on one of the delightful terraces and almost feel the water. After the Middle Ages, the River Leie, and the linen and damask industry that grew up around it, played the leading role. Successfully too! From the 18th century Kortrijk enjoyed fame as the world centre for fl ax. Thanks to the creative entrepreneurship of its people, Kortrijk grew to become the vibrant, economic heart of the region. A new Leie needs new bridges. Seven impressive examples redraw the Kortrijk skyline and aff ord it a distinctive, imposing appearance. No boring or identical copies, but seven distinctive bridges that will help both visitors and locals orientate themselves. Sometimes majestic big city structures, at other times bold zigzags. 2 CITY ON THE WATER King Albertpark and skatebowl Texture, museum of Flax and river Lys Recently King Leopold III and his horse gaze over an open park Texture tells the rich story of fl ax in three totally diff erent and the renewed Leie banks. Th e park, which is bordered by rooms. You start in the Wonder Room: a fun laboratory about the lowered river banks, forms the transition between the city fl ax in your everyday life. -

Acquisition of the Oase Aarschot Wissenstraat Site

PRESS RELEASE Regulated information 10 July 2014 – After closing of markets Under embargo until 17:40 CET Press release Acquisition of the Oase Aarschot Wissenstraat site Aedifica is pleased to announce the acquisition1 of 100 % of the shares of the BVBA Woon & Zorg Vg Aarschot on 10 July 2014. Woon & Zorg Vg Aarschot is the current owner of a plot of land and buildings in Aarschot (Wissenstraat) and was a subsidiary of the B&R group. This transaction is a part of the agreement in principle (announced on 12 June2) for the acquisition of a portfolio of five rest homes in the province of Flemish Brabant in partnership with Oase and B&R. The site in Aarschot (Wissenstraat)3 is well located in a residential area close to the city centre, approx. 20 kilometres from Leuven. The site was completed in June and recently became operational. It comprises 164 units, of which a rest home of 120 beds and an assisted-living complex of 44 apartments. Both buildings are connected underground and by an aboveground pedway. The rest home is operated by a non-profit organisation of the Oase group, on the basis of a triple net long lease of 27 years, which generates an initial triple net yield of approx. 6 %. The Oase Group operates the assisted-living apartments under an agreement for the right of use with a duration of 27 years. Aedifica may consider selling these assisted-living apartments to third parties in the short term, since they are in this transaction considered by the Company as nonstrategic assets. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/09/2021 07:17:43PM Via Free Access Chapter 1 the Cult of Saint Leonard at Zoutleeuw

Ruben Suykerbuyk - 9789004433106 Downloaded from Brill.com10/09/2021 07:17:43PM via free access Chapter 1 The Cult of Saint Leonard at Zoutleeuw Saint Leonard’s Altarpiece In July 1476, the churchwardens of Zoutleeuw gathered in a tavern to discuss commissioning an altarpiece dedicated to Saint Leonard. After their meeting, they placed an order in Brussels, and the work was finished in March 1478. The churchwardens again travelled to Brussels to settle the payment, and the retable was shipped to Zoutleeuw via Mechelen.1 The subject and the style, as well as the presence of Brussels quality marks on both the sculpture and the case of the oldest retable preserved in the Zoutleeuw church today (fig. 8), confirm that it is the very same one that was commissioned in 1476.2 Saint Leonard, the Christian hero of the altarpiece, lived in Merovingian France around the year 500. His hagiography identi- fies his parents as courtiers to King Clovis and states that he had been baptized and instructed in Christian faith by Saint Remigius, archbishop of Reims. Leonard quickly won Clovis’ goodwill, and was granted many favors by him. Not only was he allowed to free the pris- oners he visited, he was also offered a bishopric. However, preferring solitude and prayer he refused the honor and instead went to live in a forest near Limoges, where he preached and worked miracles. One of these wonders involved the pregnant queen, who had joined her husband on a hunting party in the woods and was suddenly seized by labor pains. Leonard prayed on her behalf for safe delivery. -

Linkebeek 10.23%

Geografische indicatoren (gebaseerd op Census 2011) De referentiedatum van de Census is 01/01/2011. Filters: Woningen gebouwd vanaf 1991 België Gewest Provincie Arrondissement Gemeente Sint-Gillis 2.84% Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest Arrondissement Brussel-Hoofdstad Schaarbeek 3.00% Waals Gewest Provincie Henegouwen Arrondissement Bergen Colfontaine 3.54% Vlaams Gewest Provincie Limburg Arrondissement Tongeren Herstappe 3.57% Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest Arrondissement Brussel-Hoofdstad Vorst (Brussel-Hoofdstad) 3.78% Waals Gewest Provincie Luik Arrondissement Luik Luik 4.24% Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest Arrondissement Brussel-Hoofdstad Watermaal-Bosvoorde 4.41% Farciennes 4.44% Waals Gewest Provincie Henegouwen Arrondissement Charleroi Charleroi 4.49% Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest Arrondissement Brussel-Hoofdstad Sint-Joost-ten-Node 5.36% Provincie Namen Arrondissement Philippeville Doische 5.39% Provincie Henegouwen Arrondissement Bergen Boussu 5.46% Waals Gewest Provincie Luik Arrondissement Luik Saint-Nicolas (Luik) 6.01% Arrondissement Bergen Dour 6.28% Provincie Henegouwen Arrondissement Thuin Erquelinnes 6.34% Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest Arrondissement Brussel-Hoofdstad Elsene 6.65% Waals Gewest Provincie Henegouwen Arrondissement Bergen Quaregnon 6.71% Anderlecht 6.81% Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest Arrondissement Brussel-Hoofdstad Ganshoren 6.99% Verviers 7.06% Waals Gewest Provincie Luik Arrondissement Verviers Dison 7.18% Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest Arrondissement Brussel-Hoofdstad Etterbeek 7.32% Flémalle 7.36% Provincie -

Politiezone LANDEN – LINTER

Politiezone LANDEN – LINTER - ZOUTLEEUW 1 2 JAARVERSLAG 2015 Politiezone LAN 5390 Landen – Linter – Zoutleeuw PZ LAN 5390 Populierendreef 2 3400 Landen Tel. : 011/884 884 Fax: 011/88 33 66 E-mail: [email protected] www.lokalepolitie.be/5390 3 INHOUD Voorwoord ………………………………………………………………………………….5 Beleid ………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Personeel …………………………………………………………………………………….. 8 Financiën ……………………………………………………………………………………..13 Heugelijke dagen voor de PZ LAN …………………………………………………………..17 Werking Politionele cijfers …………………………………………………………………………….23 Verkeer ………………………………………………………………………………………28 Diefstallen ……………………………………………………………………………………39 Verdovende middelen ………………………………………………………………………..49 Prorela ………………………………………………………………………………………..51 Slachtofferbejegening ………………………………………………………………………..51 Milieu ………………………………………………………………………………………..52 Contactgegevens ……………………………………………………………………………..53 4 VOORWOORD Nooit hadden we het ons in het hoofd gehaald. We hadden het zelfs niet kunnen en willen denken. “De inhuldiging van het nieuw politiehuis met langs alle zijden van de site zwaar bewapende politie-inspecteurs”. Was dit in Landen? En met dit contrast van feest en dreiging zal 2015 in ons geheugen gegrift blijven. 2015 was voor de lokale politie van de PZ LAN het jaar van de grote metamorfose, tenminste op het vlak van huisvesting. Het nieuw commissariaat op Hasco was een feit en burgers en medewerkers zouden voortaan krijgen waar ze recht op hadden, namelijk een aangepaste ruimte waar dienstverlening een ander gezicht kon krijgen. En ondanks een veelvoud