“Windows on the West: Foreign Television Programming in Hungary and the Future of U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

Television Advertising Insights

Lockdown Highlight Tous en cuisine, M6 (France) Foreword We are delighted to present you this 27th edition of trends and to the forecasts for the years to come. TV Key Facts. All this information and more can be found on our This edition collates insights and statistics from dedi cated TV Key Facts platform www.tvkeyfacts.com. experts throughout the global Total Video industry. Use the link below to start your journey into the In this unprecedented year, we have experienced media advertising landscape. more than ever how creative, unitive, and resilient Enjoy! / TV can be. We are particularly thankful to all participants and major industry players who agreed to share their vision of media and advertising’s future especially Editors-in-chief & Communications. during these chaotic times. Carine Jean-Jean Alongside this magazine, you get exclusive access to Coraline Sainte-Beuve our database that covers 26 countries worldwide. This country-by-country analysis comprises insights for both television and digital, which details both domestic and international channels on numerous platforms. Over the course of the magazine, we hope to inform you about the pandemic’s impact on the market, where the market is heading, media’s social and environmental responsibility and all the latest innovations. Allow us to be your guide to this year’s ACCESS OUR EXCLUSIVE DATABASE ON WWW.TVKEYFACTS.COM WITH YOUR PERSONAL ACTIVATION CODE 26 countries covered. Television & Digital insights: consumption, content, adspend. Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, Croatia, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Hungary, India, Italy, Ireland, Japan, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Russia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, UK and the US. -

Edition 2016 Entertain. Inform. Engage

EDITION 2016 FULL YEAR RESULTS ENTERTAIN. INFORM. ENGAGE. KEY FIGURES SHARE PRICE PERFORMANCE 01/01/2016 – 31/12/2016 + 6.8 % MDAX INDEX = 100 – 7.6 % EURO STOXX 600 MEDIA – 9.5 % RTL GROUP – 21.7 % PROSIEBENSAT1 RTL Group share price development for January to December 2016 based on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange (Xetra) against MDAX, Euro Stoxx 600 Media and ProSiebenSat1 11.5 % OTHER 10.7 % DIGITAL 48.0 % 21.2 % TV ADVERTISING CONTENT 4.5 % PLATFORM REVENUE 4.1 % RADIO ADVERTISING RTL Group Revenue Split In 2016, TV advertising accounted for 48.0 per cent of RTL Group’s total revenue, making the Group one of the most diversified groups when it comes to revenue. Content represented 21.2 per cent of the total, while greater exposure to fast-growing digital revenue streams and higher margin platform revenue will further improve the mix. 2 RTL Group Full-year results 2016 Key figures REVENUE 2012 – 2016 (€ million) EBITA 2012 – 2016 (€ million) 16 6,237 16 1,205 15 6,029 15 1,167 14 5,808 14 1,144* 13 5,824* 13 1,148** 12 5,998 12 1,078 * Restated for IFRS 11 * Restated for changes in purchase price allocation ** Restated for IFRS 11 NET PROFIT ATTRIBUTABLE TO RTL GROUP SHAREHOLDERS 2012 – 2016 (€ million) EQUITY 2012 – 2016 (€ million) 16 720 16 3,552 15 789 15 3,409 14 652* 14 3,275* 13 870 13 3,593 12 597 12 4,858 * Restated for changes in purchase price allocation * Restated for changes in purchase price allocation TOTAL DIVIDEND/ MARKET CAPITALISATION* 2012 – 2016 (€ billion) DIVIDEND YIELD PER SHARE 2012 – 2016 (€ ) (%) 16 10.7 16 -

Annual Report 2008 Annual Report the Leadingeuropeanentertainment Network

THE LEADING EUROPEAN ENTERTAINMENT NETWORK FIVE-YEAR SUMMARY 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 €m €m €m €m €m Revenue 5,774 5,707 5,640 5,115 4,878 RTL Group – of which net advertising sales 3,656 3,615 3,418 3,149 3,016 Corporate Communications Other operating income 37 71 86 103 118 45, boulevard Pierre Frieden Consumption of current programme rights (2,053) (2,048) (1,968) (1,788) (1,607) L-1543 Luxembourg Depreciation, amortisation and impairment (203) (213) (217) (219) (233) T: +352 2486 5201 F: +352 2486 5139 Other operating expense (2,685) (2,689) (2,764) (2,518) (2,495) www.RTLGroup.com Amortisation and impairment of goodwill ANNUAL REPORT and fair value adjustments on acquisitions of subsidiaries and joint ventures (395) (142) (14) (16) (13) Gain/(Loss) from sale of subsidiaries, joint ventures and other investments (9) 76 207 1 (18) Profit from operating activities 466 762 970 678 630 Share of results of associates 34 60 72 63 42 Earnings before interest and taxes (“EBIT”) 500 822 1,042 741 672 Net interest income/(expense) 21 (4) 2 (11) (25) Financial results other than interest 7 26 33 2 (19) Profit before taxes 528 844 1,077 732 628 Income tax income/(expense) (232) (170) 34 (116) (196) Profit for the year 296 674 1,111 616 432 Attributable to: RTL Group shareholders 194 563 890 537 366 Minority interest 102 111 221 79 66 Profit for the year 296 674 1,111 616 432 EBITA 916 898 851 758 709 Amortisation and impairment of goodwill (including disposal group) and fair value adjustments on acquisitions of subsidiaries and joint ventures -

Appendix to the Responses of the Government of Hungary to the List Of

Appendix to the Responses of the Government of Hungary to the list of issues and questions with regard to the consideration of the combined seventh and eighth periodic report (CEDAW/C/HUN/7-8) Annex no. 1 Important cases of legal violations established by the Media Council 2008 RTL Klub – Fábry Show In decision no.583/2008. (III. 26.) the ORTT (National Committee for Radio and Television) found that the RTL Klub programme titled "Fábry Show" had committed a legal violation when the presenter, while discussing domestic political issues, made strong, vulgar comments of a sexual nature about the leader of the Hungarian Socialist Party faction, the largest governing party in parliament. Although the presenter apologised to the faction leader, he later countered his statement, noting that the government could also apologise for what they had done, in the light of which the earlier image is not an exaggeration. In the view of the Committee, what was said in that part of the programme put the socialist politician in an undignified and vulnerable position, and hurt her human dignity by making jokes which reduced her to a sexual object. The ORTT (the legal predecessor, until 2010, to the present media authority) found that the broadcasting company Magyar RTL Televízió Zrt. was in breach of Act I of 1996 on radio and television broadcasting (hereafter: Radio and TV Act),1 paragraph 3 (2) (protection of the right to human dignity in the media). In view of the breach, the Committee called upon the programme broadcaster to discontinue its unlawful conduct. 2009 TV2 - Mokka ("Mocha") In decision no. -

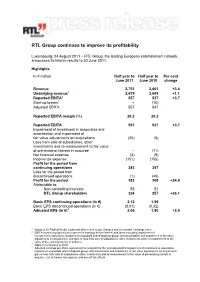

RTL Group Continues to Improve Its Profitability

RTL Group continues to improve its profitability Luxembourg, 24 August 2011 − RTL Group, the leading European entertainment network, announces its interim results to 30 June 2011. Highlights In € million Half year to Half year to Per cent June 2011 June 2010 change Revenue 2,751 2,661 +3.4 Underlying revenue1 2,679 2,649 +1.1 Reported EBITA2 557 537 +3.7 Start-up losses3 − (10) Adjusted EBITA 557 547 Reported EBITA margin (%) 20.2 20.2 Reported EBITA 557 537 +3.7 Impairment of investment in associates and amortisation and impairment of fair value adjustments on acquisitions (20) (5) Loss from sale of subsidiaries, other investments and re-measurement to fair value of pre-existing interest in acquiree − (11) Net financial expense (3) (9) Income tax expense (151) (155) Profit for the period from continuing operations 383 357 Loss for the period from discontinued operations (1) (49) Profit for the period 382 308 +24.0 Attributable to: Non-controlling interests 58 51 RTL Group shareholders 324 257 +26.1 Basic EPS continuing operations (in €) 2.12 1.99 Basic EPS discontinued operations (in €) (0.01) (0.32) Adjusted EPS (in €)4 2.06 1.90 +8.4 1 Adjusted for Radical Media, Ludia and other minor scope changes and at constant exchange rates 2 EBITA (continuing operations) represents earnings before interest and taxes excluding impairment of investment in associates, impairment of goodwill and of disposal group, and amortisation and impairment of fair value adjustments on acquisitions, and gain or loss from sale of subsidiaries, other investments -

Philippines in View Philippines Tv Industry-In-View

PHILIPPINES IN VIEW PHILIPPINES TV INDUSTRY-IN-VIEW Table of Contents PREFACE ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. MARKET OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. PAY-TV MARKET ESTIMATES ............................................................................................................................... 6 1.3. PAY-TV OPERATORS .......................................................................................................................................... 6 1.4. PAY-TV AVERAGE REVENUE PER USER (ARPU) ...................................................................................................... 7 1.5. PAY-TV CONTENT AND PROGRAMMING ................................................................................................................ 7 1.6. ADOPTION OF DTT, OTT AND VIDEO-ON-DEMAND PLATFORMS ............................................................................... 7 1.7. PIRACY AND UNAUTHORIZED DISTRIBUTION ........................................................................................................... 8 1.8. REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT .............................................................................................................................. -

C72f99e6-0E06-4C50-A755-473Aab0b2680 Worldreginfo - C72f99e6-0E06-4C50-A755-473Aab0b2680 Key Figures 2008 – 2012

WorldReginfo - c72f99e6-0e06-4c50-a755-473aab0b2680 WorldReginfo - c72f99e6-0e06-4c50-a755-473aab0b2680 Key Figures 2008 – 2012 shAre PriCe PerFormanCe 2008 – 2012 – 6.5 % (2012: – 1.9 %) INDEX = 100 rTl group dJ sToXX – 16.1 % (2012: + 17.5 %) r evenue (€ million) e quiTy (€ million) 12 5,998 12 4,858 11 5,765 11 5,093 10 5,532 10 5,597 09 5,156 09 5,530 08 5,774 08 5,871 e BiTA (€ million) M ArKeT Capitalisation (€ billion)* 12 1,078 12 11.7 11 1,134 11 11.9 10 1,132 10 11.9 09 796 09 7.3 08 916 08 6.6 *Asof31December n eT ProFiT AttriButaBle To rTl grouP shAreholders (€ million) To tal dividend Per shAre (€ ) 12 597 12 10.50 11 696 11 5.10 10 611 10 5.00 09 205 09 3.50 08 194 08 3.50 Dividend payout 2008− 2012: € 4.2 billion WorldReginfo - c72f99e6-0e06-4c50-a755-473aab0b2680 2012 A nnuAl rePorT T he leAding euro PeAn en TerTAinMenT n eTworK WorldReginfo - c72f99e6-0e06-4c50-a755-473aab0b2680 RTL Television’s AlarmfürCobra11, Germany’s most popular action series, has become a hit format in some 140 countries around the globe. Since 2012, it has been one of the signature series of the newly launched action channel, Big RTL Thrill, in India WorldReginfo - c72f99e6-0e06-4c50-a755-473aab0b2680 ConTenTs Corporate information 6 Chairman’s statement 8 Chief executives’ report 14 Profit centres at a glance 16 The year in review 16 Broadcast 34 Content 60 Digital 72 Red Carpet 76 Corporate responsibility 92 Operations 94 How we work 96 The Board / executive Committee Financial information 104 directors’ report 110 Mediengruppe RTL Deutschland 114 Groupe M6 117 FremantleMedia 120 RTL Nederland 123 RTL Belgium 126 RTL Radio (France) 128 Other segments 143 Management responsibility statement 144 Consolidated financial statements 149 Notes 210 Auditors’ report 212 RTl group overview 214 Credits 215 Fully consolidated profit centres at a glance 217 Five-year summary WorldReginfo - c72f99e6-0e06-4c50-a755-473aab0b2680 irman’s ChA enT stateM Thomas rabe ChairmaN of The board of DiRectors In 2012, RTL Group delivered solid financial results. -

2013 Post Hispanic Upfront Television Guide a Digital Supplement to Broadcasting & Cable and Hispanicad.Com

2013 post hispanic upfront television guide a digital supplement to broadcasting & cable and hispanicad.com With Drop Shadow Published by: Without Drop Shadow For Black Background For Black & White in color For Black & White in color For Black & White in white mcn_standard.indd 3 5/15/2013 8:29:52 PM Q A THE QUEST TO& CLOSE THE AD GAP UNIVISION’S CESAR CONDE BELIEVES HISPANIC TELEVISION WILL CONTINUE TO GROW. CONVINCING CLIENTS TO PARTICIPATE REMAINS AN INDUSTRY FRUSTRATION. Univision Networks president Cesar Conde is excited about the attention Spanish- language television—and forthcoming English-language offerings targeting Latinos— is getting from the mainstream media. In this Q&A with Adam R Jacobson, Conde discusses his network’s plans for 2013, including its digital initiatives and the vital importance of research in making the proper programming decisions across all screens. Spanish-language Adam R Jacobson: Cesar Conde: As evidenced by the have witnessed rst-hand the power of television conti nues to att ract the lion’s number of new Hispanic o erings Spanish-language media. e challenge share of Hispanic adverti sing dollars, cropping up across the media industry for us all is to close the ad gap. and new networks have emerged in the these days, the size, importance and last year—namely MundoFox, Univision Univision seems to be a in uence of the U.S. Hispanic community ARJ: Deportes, TLNovelas, and the revamped communicati ons company in is nally receiving the widespread NuvoTV. It’s clear that the thirst for transformati on, with TeleFutura acknowledgement it deserves. -

PDF ATF Dec12

> 2 < PRENSARIO INTERNATIONAL Commentary THE NEW DIMENSIONS OF ASIA We are really pleased about this ATF issue of world with the dynamics they have for Asian local Prensario, as this is the first time we include so projects. More collaboration deals, co-productions many (and so interesting) local reports and main and win-win business relationships are needed, with broadcaster interviews to show the new stages that companies from the West… buying and selling. With content business is taking in Asia. Our feedback in this, plus the strength and the capabilities of the the region is going upper and upper, and we are region, the future will be brilliant for sure. pleased about that, too. Please read (if you can) our central report. There THE BASICS you have new and different twists of business devel- For those reading Prensario International opments in Asia, within the region and below the for the first time… we are a print publication with interaction with the world. We stress that Asia is more than 20 years in the media industry, covering Prensario today one of the best regions of the world to proceed the whole international market. We’ve been focused International with content business today, considering the size of on Asian matters for at least 15 years, and we’ve been ©2012 EDITORIAL PRENSARIO SRL PAYMENTS TO THE ORDER OF the market and the vanguard media ventures we see attending ATF in Singapore for the last 5 years. EDITORIAL PRENSARIO SRL in its main territories; the problems of the U.S. and As well, we’ve strongly developed our online OR BY CREDIT CARD. -

Full-Year Results 2020

FULL-YEAR RESULTS 2020 ENTERTAIN. INFORM. ENGAGE. KEY FIGURES +18.01 % SDAX +8.77 % MDAX SHARE PERFORMANCE 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020 in per cent INDEX = 100 -7.65 % SXMP -9.37 % RTL GROUP -1.11 % PROSIEBENSAT1 RTL Group share price development for January to December 2020 based on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange (Xetra) against MDAX/SDAX, Euro Stoxx 600 Media and ProSiebenSat1 RTL GROUP REVENUE SPLIT 8.5 % OTHER 17.5 % DIGITAL 43.8 % TV ADVERTISING 20.0 % CONTENT 6.7 % 3.5 % PLATFORM REVENUE RADIO ADVERTISING RTL Group’s revenue is well diversified, with 43.8 per cent from TV advertising, 20.0 per cent from content, 17.5 per cent from digital activities, 6.7 per cent from platform revenue, 3.5 per cent from radio advertising, and 8.5 per cent from other revenue. 2 RTL Group Full-year results 2020 REVENUE 2016 – 2020 (€ million) ADJUSTED EBITA 2016 – 2020 (€ million) 20 6,017 20 853 19 6,651 19 1,156 18 6,505 18 1,171 17 6,373 17 1,248 16 6,237 16 1,205 PROFIT FOR THE YEAR 2016 – 2020 (€ million) EQUITY 2016 – 2020 (€ million) 20 625 20 4,353 19 864 19 3,825 18 785 18 3,553 17 837 17 3,432 16 816 16 3,552 MARKET CAPITALISATION* 2016 – 2020 (€ billion) TOTAL DIVIDEND/DIVIDEND YIELD PER SHARE 2016 – 2020 (€ ) (%) 20 6.2 20 3.00 8.9 19 6.8 19 NIL* – 18 7.2 18 4.00** 6.3 17 10.4 17 4.00*** 5.9 16 10.7 16 4.00**** 5.4 *As of 31 December *On 2 April 2020, RTL Group’s Board of Directors decided to withdraw its earlier proposal of a € 4.00 per share dividend in respect of the fiscal year 2019, due to the coronavirus outbreak ** Including -

How RTL Group Gives Back to Society (2013)

corporaTe responsibiliTy how In 1924, a sole radio transmitter broadcast from Luxembourg. Today, RTL Group has a portfolio of 53 TV channels in ten countries. RTL Group’s worldwide production arm – which adopted the company rTl group name FremantleMedia in 2001 – grew its revenues by 128 per cent to € 1.7 billion since its inception. gives back To socieTy Corporate responsibility Corporate responsibility company overview: best-in-class european entertainment company helping, The iLuxembourgbasednforming, company has interests in TV channels and radio BROADCAST stationsp inromo Germany,Ting France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Strong #1 or #2 in attractive Spain, Hungary, Tions Croatia, and India. key countries It is one solu of the world’s leading producers of television content, such as CONTENT talent and game shows, drama, daily soaps and telenovelas, including Global leader in TV entertainment production, exploitation and distribution Idols, Got Talent, The X Factor, Good Times − Bad Times and Family Feud. DIGITAL The roots of the company date back to 1924, when Radio Luxembourg At the forefront of the digital and fi rst went on air. Compagnie Luxembourgeoise de Radiodiffusion (CLR) non-linear transition was founded in 1931. As a Euro pean pioneer, the company broadcast a TEAM unique programme in several languages using the same frequency. Highly experienced international manage- RTL Group itself was created in spring 2000 following the merger of ment team with an integrated approach Luxembourgbased CLTUFA and the British content production company RESULTS Pearson TV,Television owned by UK media group Pearson will PLC. CLTUFA itself was Strong track record of delivering created in 1997 when the shareholders of UFA (Bertelsmann) and the fi nancial results historic Compagnie Luxembourgeoise de Télédiffusion – CLT (Audiofi na) merged their TV, radioremain and TV production businesses.