Master's Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simulation of Supply/Demand Balance

The Study on Power Network System Master Plan in Lao PDR Draft Final Report (Stage 3) Simulation of Supply/Demand Balance 17.1. Options for Power Development Plan up to 2030 In order to examine supply reliability and supply-demand balance based on the Lao PDR’s development situation, and considering the development status of the country’s power supply facilities and transmission facilities, a simulation is conducted for 2030. Laos’s power system is examined up to 2030 considering the demand situation in the domestic system and the expansion plans for transmission lines. The northern and central 1 areas are put together to form a Laos NC system, the central 2 a Laos C system, and the southern part an S system. Based on the results of the supply/demand balance simulations, we make recommendations for power plant expansion plans and transmission lines, and for interconnections with neighboring countries. Power Development Plan for Laos’ domestic system up to 2030 1. Power plants for analysis of supply/demand balance in Laos In examining the supply/demand balance for domestic demand in Laos up to 2030, we use the power plan approved by the MEM Minister (see Table 17.1-1). Table 17.1-1 Power Development Plan approved by minister of MEM, including existing plants No Power Plant MW Type COD Province Region 1 Nam Dong 1.00 Run of river 1970 Luangprabang NC 2 Nam Ngum 1 155.00 Reservoir 1971 Vientiane Pro NC 3 Nam Ko 1.50 Run of river 1996 Oudomxay NC 4 Nam Luek 60.00 Reservoir 2000 Saysomboun NC 5 Nam Mang 3 40.00 Reservoir 2004 Vientiane Pro -

Annual Opium Poppy Survey 1999/2000

LAO NATIONAL COMMISSION ON DRUG CONTROL AND SUPERVISION Annual Opium Poppy Survey 1999/2000 With the support of UNDCP – Laos and the Illicit Crops Monitoring Programme. Vientiane, October 2000 Table of contents Summary.......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 4 I. The 2000 National Opium Survey............................................................................. 5 Objectives..................................................................................................................... 5 Methodology................................................................................................................. 5 The Baseline............................................................................................................. 5 The Random Sample................................................................................................ 5 The Interviews and Field Measurement.................................................................... 6 The opium growing farmers interview ....................................................................... 6 The field measurement ............................................................................................. 6 Organisation and Staff.................................................................................................. 7 Training ....................................................................................................................... -

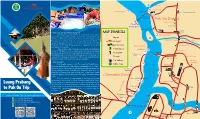

Chomphet Brochure Back A3

6 Pha Ane Cliff 4 Ban Pak Ou Ban Muang Keo 7 Wat Pak Ou Way to Oudomxay Province 3 Elephant Camp Phone Travel Pak Ou District 5 Ban Huoay Mad Tham Ting Or Pak Ou Cave Indigo farm Manifa Elephant Camp Way to 1. Ban Xang Khong and Ban Xieng Lek MAP SYMBOLS Pak Ou Ban Xang Kong and Ban Xieng Lek are well known villages which 2 Ban Xang Hai produce Posa paper made from mulberry bark and also a style of silk weaving Airport which is very different from others in Laos. You can watch the villagers making 8 Ban Pak Seuang Posa paper (from mulberry bark) and weaving traditional textiles. You’ll see Boat pier Donkhoun Island Ban Viang Sa Vanh this paper around town at the markets, as menus in restaurants and a visit to Ban Xieng Lek and Ban Xang Khong gives you the opportunity to understand Bus Terminal Ban Sen Souk first-hand the way it is made. Ban Muang Kham Where are these villages? 3 kilometers to the north of Luang Prabang Petrol station Wat Khokphap , across the Nam Khan river. These villages can be reached by tuk tuk (though 9 Ban Pha O you will need to cross by the new bridge) and by bicycle (old bridge) or even on Restaurant Boat Terminal foot( bamboo bridge). After crossing the old bridge, turn first left and follow the Wat Nong Sa Keo road as it turns north along the Mekong River. You’ll see craft shops and probably Temple Ban Phon Sai the mulberry paper drying outside in the sun as you approach. -

Use of Living Aquatic Resources in the Livelihood of Rural People and Fisheries Management in the Nam Ou River

Use of Living Aquatic Resources in the Livelihood of Rural People and Fisheries Management in the Nam Ou River 平成 19 年編入 Country:Laos PHOUSAVANH PHOUVIN Keywords: Aquatic resources, Lao PDR, Ou River, fishery management, fish conservation zone, indigenous fish specie, edible aquatic animal, aquatic plant. Introduction The main ecosystem for living aquatic resources in the north of Lao PDR is the Nam Ou or Ou River and its associated waterways and wetlands, which provide a myriad of habitats for the richness of aquatic life forms in the country. The fisheries ecology of the Nam Ou basin is intimately linked to, and influenced by, the morphological and hydrological characteristics of the basin. One of the main driving forces for fishery ecological processes is the Fig 1. The photo of physical separation of important wet season feeding habitats and dry upstream river in Tay village, season habitats. The fish and other aquatic resources from this Gnot Ou district Phongsaly ecosystem that are not domestically consumed are commercialized province. and generate income for the primary producer as well as for the people involved in fish preservation and marketing. As well as being an important source of income for many rural households, fish and other aquatic products also directly contribute to the food security of the Lao PDR population. The research survey is very important to find out the problems and challenges to further sustainable development in Laos in the areas of water resource management, fisheries and fisheries Fig 2. The photo of management, aquatic resource use and conservation. downstream river in Pak Ou village, Pak Ou district Research Objectives Luangphabang province. -

Socio-Economic Survey and Analysis to Identify Drivers of Forest Changes in Houay Khing and Sop Chia Village Clusters

Socio-economic Survey and Analysis to Identify Drivers of Forest Changes in Houay Khing and Sop Chia Village Clusters, Phonxay District, Luang Prabang January 2012 Vientiane, Lao PDR (left blank) Abbreviation and Acronyms CESVI Cooperazione e Sviluppo (Cooperation and Development) DAFO District Agriculture and Forestry Office GDP Growth Domestic Product GoL Government of Lao PDR GPAR Governance and Public Administration Reforms HH Household HK Houay Khing JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency MAF Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry MI Mekong Institute (Thailand) MoIC Ministry of Industry and Commerce MURC Mitsubishi UFJ Research & Consulting NGPES National Growth and Poverty Eradication NTFP Non-Timber Forest Product PADETC Participatory Development Training Centre PAFO Provincial Agriculture and Forestry Office PAREDD Participatory Land and Forest Management Project for Reducing Deforestation PDR Peoples’ Democratic Republic (Lao) PICO Provincial Industry and Commerce Office REDD+ Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation Plus SC Sop Chia TABI The Agrobiodiversity Initiative ToR Terms of Reference UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization VCA Value Chain Analysis i Table of Contents Abbreviation and Acronyms .................................................................................... i Chapter 1 Scope of the Survey ............................................................................... 1 1.1. Background ......................................................................................................................................... -

Lao People’S Democratic Republic: Greater Mekong Subregion Tourism Infrastructure for Inclusive Growth Project

Initial Environmental Examination __________________________________________ April 2014 Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Greater Mekong Subregion Tourism Infrastructure for Inclusive Growth Project Oudomxay, Luang Prabang and Khammouane Provinces Prepared by the Ministry of Information, Culture and Tourism, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, for the Asian Development Bank CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (January 2014) Currency Unit – kip K R1.00 = $0.00012 $1.00 = K8,300 ABBREVIATIONS DOH - Department of Heritage DAF - Department of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries EA - environmental assessment EIA - environment impact assessment ECC - environmental compliance certificate ECO - environmental control officer EMP - environment monitoring plan ESIA - environment and social impact assessment EA - executing agency GMS - Greater Mekong Subregion IA - implementing agency IEE - initial environmental examination IUCN - International Union for Conservation of Nature Lao PDR - Lao People’s Democratic Republic LWU - Lao Women’s Union MAF - Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries MICT - Ministry of Information, Culture and Tourism MOF - Ministry of Finance MONRE - Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment MPWT - Ministry of Public Works and Transport MRC - Mekong River Commission NBSAP - National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan NPA - national protected area O&M - operation and maintenance PIU - project implementation unit PCU - project coordination unit PPP - public-private partnership REA - rapid environment assessment TSS - total suspended solids UXO - unexploded ordnance WREA - Water Resources and Environment Agency WEIGHTS AND MEASURES km: kilometer kg: kilogram ha: hectare mm: millimeter NOTES In this report, "$" refers to US dollars unless otherwise stated. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. -

Indigenous Peoples Plan ______

GMS Tourism Infrastructure for Inclusive Growth Project (RRP LAO 46293-003) Indigenous Peoples Plan __________________________________________ November 2013 Lao People‘s Democratic Republic: Greater Mekong Subregion Tourism Infrastructure for Inclusive Growth Project This indigenous peoples plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 31 January 2013) 1USD = KN 7,874 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank AP affected persons CTG community tourism group DICT Department of Information, Culture and Tourism DMST double bituminous surface treatment DMO destination management organization GMS Greater Mekong Subregion Government Government of Lao PDR IPP indigenous peoples plan Lao PDR Lao People‘s Democratic Republic LNFR Lao National Front for Reconstruction LWU Lao Women‘s Union MICT Ministry of Information, Culture and Tourism PCU project coordination unit PIB public information booklet PIU project implementation unit PPTA project preparation technical assistance RP resettlement plan SES socioeconomic survey WEIGHTS AND MEASURES km kilometer kg kilogram ha hectare m meter m2 square-meters NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of the Lao PDR ends on 31 October. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 I. BACKGROUND 1 A. Objectives of the Indigenous Peoples Plan 1 B. Project Description 1 II. SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT 2 A. Ethnic Groups in Lao PDR 2 B. Policy Context of Ethnic Group Development in Lao PDR 3 C. ADB Safeguard Policy 3 D. Ethnic Profile in Project Locations 4 E. -

Mobility and Heritage in Northern Thailand and Laos: Past and Present

and Heritage rn Thailand and Laos: Past and Present Prooeedlngs of the Chiang Mai Conterence. 1 - 2 December 2011 Mobility and Heritage in Northern Thailand and Laos: Past and Present Mobility and Heritage in Northern Thailand and Laos: Past and Present Proceedings 0/ the Chiang Mai Conference, 1 - 2 December 20 11 Editedby Olivier Evrar~ Dominique Cuillaud Chqyan Vaddhanaphuti Post/ace by Charles F. Keyes 4 Mobility andheritage in Northern Thailand andLaostpastandpresent Copyright © 2013 Institut de Recherche pour le Developpement, Printed in Chiang Mai at Good Print. National Library of Thailand Cataloging in Publication Data Evrard,Olivier. Mobility and Heritage in Northern Thailand and Laos: Past and Present.-- Chiang Mai : Center for Ethnic Studies and Development, Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University, 2013. 302p. 1. Thailand--History. 2. Laos--History. 1.Guillaud, Dominique, jt. auth. Il. Vaddhanaphuti, Chayan, jt. auth. rv Billault, Laurence, ill. V. Tide. 959.3 ISBN 978-974-672-822-5 Cover picture © Olivier Evrard Lamet woman walking toward her field hut. Ban Takrong, Pha Oudom district, Bokeo province, Lao PD.R. Layout: Laurence Billault illustration & cartography: Laurence Btllault, Elisabeth Habert Institut de Recherche pour le Developpernent : http://wwmirdfr/ PALOC: http://www.paloc.irdfr/ Center for Ethnic Studies and Development, Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University. http://www.cesdsoc.cmu.ac.th/ Contents Contents Authors 9 Introduction 11 Mobility and Heritage in Northern Thailand and Laos: Past and Present 11 DOMINIQUE GUILLAUD CHAYAN VADDHANAPHUTI Part 1 Historic andSymbolic Traces ofSedentz"sm 25 1. Sedentarity and metallurgy in upland Southeast Asia 27 OLIVER PRYCE 2. Foucling,deserting and returning: the impeded sedentism of Northern Tai populations. -

Technical Assistance Consultant's Report

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 49387-001 June 2018 Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Second GMS Tourism Infrastructure for Inclusive Growth Project (Financed by ADB PPTA) The document is prepared by Norconsult AS(NORWAY) in association with NORCONSULT MANAGEMENT SERVICES, INC. (PHILIPPINES) For Ministry of Information, Culture and Tourism, Lao PDR This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Appendix 11: Project Climate Risk Assessment and Management TA9090-REG: Preparing the Second Greater Mekong Subregion Tourism Infrastructure for Inclusive Growth Project FINAL REPORT – PART C June 2018 Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Second Greater Mekong Subregion Tourism Infrastructure for Inclusive Growth Project Appendix 11 Project Climate Risk Assessment and Management1 I. Basic Project Information Project Title: Second Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Tourism Infrastructure for Inclusive Growth Project Project Budget: $47 million ADB; Government $1.78 million Location: Champasak and Vientiane Provinces, Lao Peoples Democratic Republic Sector: Transport; Water and other Urban Infrastructure and Services; Industry and Trade Theme: Inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, regional integration Brief Description (particularly highlighting aspects of the project that could be affected by weather/climate conditions): The project will help transform secondary GMS central and southern corridor towns into economically inclusive, competitive tourism destinations by improving transport infrastructure, urban environmental services, and capacity to sustainably manage tourism growth. Residents in project areas are expected to directly benefit from climate-resilient infrastructure development and increased access to economic opportunities. -

Sustainable Sloping Lands and Watershed Management Linking Research to Strengthen Upland Policies and Practices

Booklet for the International Conference on Sustainable Sloping Lands and Watershed Management Linking research to strengthen upland policies and practices December 12 - 15, 2006 Luang Prabang, Lao PDR About NAFRI The National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute of Laos was established in 1999 in order to consolidate agriculture and forestry research activities within the country and develop a coordinated National Agriculture and Forestry Research System. NAFRI aims to contribute to the goals of the Government of Laos by focusing on adaptive re- search to overcome specific problems limiting production and causing degradation of natural resources. NAFRI seeks to do this by carrying out demand-driven research that supports local peoples’ active involvement in their own development. NAFRI focuses primarily on adaptive research in order to provide technical options, recommen- dations and results to support agriculture, forestry and fisheries development and strategic formulation of policies and programmes in accordance with the government policy. NAFRI is comprised of seven discipline specific research Centres and one regional research Centre. These include: 1. Agriculture Research Centre 2. Coffee Research Centre 3. Forest Research Centre 4. Horticulture Research Centre 5. Livestock Research Centre 6. Living Aquatic Resources Research Centre 7. Soil Science and Land Classification Centre 8. Northern Agriculture and Forestry Research Centre National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute PO Box 7170 Vientiane, Lao PDR Tel: (021) -

![[Draft Implementing Decree for New FIL]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3268/draft-implementing-decree-for-new-fil-4803268.webp)

[Draft Implementing Decree for New FIL]

Authentic in Lao Only LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC Peace Independence Democracy Unity Prosperity Prime Minister’s office No. 301/PM Vientiane Capital, dated 12 October 2005 Decree of the Prime Minister Regarding the Implementation of The Law on the Promotion of Foreign Investment - Pursuant to the Law on the Government of the Lao PDR No. 02/NA, dated 6 May 2003; - Pursuant to the Law on the Promotion of Foreign Investment No. 11/NA, dated 22 October 2004; - Referencing to the proposal of the President of the Committee for Planning and Investment. SECTION I General Provisions Article 1. Objective This Decree is set out to implement the Law on the Promotion of Foreign Investment correctly to the objectives and uniformly throughout the country on the principles, methods and measures regarding the promotion, protection, inspection, resolution of disputes, policies towards productive persons and measures against the violators. Article 2. Legal Guarantees The State provides legal guarantees to foreign investors who are established under the Law on the Promotion of Foreign Investment as follows: 2.1 administer by Law and regulation on the basis of equality and mutual interests; 2.2 undertake all of the State’s obligations under the laws, international treaties in which the State is a party, the Agreement Regarding the Page 1 of 61 Promotion and Protection of Foreign Investment and the agreements that the government has signed with the foreign investor; 2.3 do not interfere with the legally business operation of foreign investors. Article 3. Capital Contribution which is an Intellectual Property The State recognizes the shared capital contribution of the enterprises which is an intellectual property; the evaluation of the intellectual property value shall be determined in detail by the scope of rights, obligations and interest in the resolution of a shareholders’ meeting and the business joint venture agreement of the enterprise. -

Nam Ou River Cascade Hydropower Project Nam Ou River

(https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/) Home (Https://Www.Nsenergybusiness.Com) » Projects (Https://Www.Nsenergybusiness.Com/Projects) » Nam Ou River Cascade Hydropower Project Nam Ou River Cascade Hydropower Project POWER (HTTPS://WWW.NSENERGYBUSINESS.COM/./POWER/) HYDRO (HTTPS://WWW.NSENERGYBUSINESS.COM/POWER/HYDRO) DAM (HTTPS://WWW.NSENERGYBUSINESS.COM/HYDRO/DAM) Plant Type : Location : Capacity : Construction Started : Cascade hydropower project Phongsaly province-Luang Prabang 1,272MW October 2012 i L MORE Nam Ou river cascade hydropower project (HPP) is being developed on the banks of the Nam Ou river, which is the largest tributary of Mekong River (ht intp Laos.s://twitter.com/intent/tweet? (htt Ou+River+TheCa hydropowerscade+H projectydro (https://wwwpower+P.nsenerrojegybusiness.com/projects/rogun-hydropowerct&url=https%3A%2F%2Fw-project/)ww.n hassenergybusiness.com%2Fprojects%2Fnam-url=https://w seven isolated cascadeou units-riv beinger- cconstructedascade in-h difyferentdrop districtsower along-pro theje cNamt% Ou2F River&vi.a The=NS+Energy) ou-ri cascade units are being developed in two phases with a cumulative capacity of 1,272MW. The project is owned by Laos State Electricity Corporation, Electricite du Laos (EDL). It is being developed by a joint venture of EDL (20%) and Sinohydro (80%), a subsidiary of Power China, under a 25-year build, operate and transfer (BOT) agreement signed in April 2011. The estimated investment in the project is £2.1bn ($2.73bn). Phase one of the project consisting of three units with a total installed capacity of 540MW was commissioned in January 2017. PROJECT GALLERY The construction work on phase two, which comprises of four units with a total installed capacity of 732MW, began in April 2016.