Scaling out Impacts: a Study of Three Methods for Introducing Forage Technologies to Villages in Lao PDR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of the EC Cooperation with the LAO

Evaluation of EC co-operation with the LAO PDR Final Report Volume 2 June 2009 Evaluation for the European Commission This evaluation was commissioned by: Italy the Evaluation Unit common to: Aide à la Décision Economique Belgium EuropeAid Co-operation Office, Directorate-General for Development and PARTICIP GmbH Germany Directorate-General for External Relations Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik Germany Overseas Development Institute United Kingdom European Institute for Asian Studies Belgium Istituto Complutense de Estudios Internacionales Spain The external evaluation team was composed of Landis MacKellar (team leader), Jörn Dosch, Maija Sala Tsegai, Florence Burban, Claudio Schuftan, Nilinda Sourinphoumy, René Madrid, Christopher Veit, Marcel Goeke, Tino Smaïl. Particip GmbH was the evaluation contract manager. The evaluation was managed by the evaluation unit who also chaired the reference group composed by members of EC services (EuropeAid, DG Dev, DG Relex, DG Trade), the EC Delegations in Vientiane and Bangkok and a Representative of the Embassy of the LAO PDR. Full reports of the evaluation can be obtained from the evaluation unit website: http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/how/evaluation/evaluation_reports/index_en.htm The opinions expressed in this document represent the authors’ points of view, which are not necessarily shared by the European Commission or by the authorities of the countries concerned. Evaluation of European Commission’s Cooperation with ASEAN Country Level Evaluation Final Report The report consists of 2 volumes: Volume I: FINAL REPORT Volume II: Annexes VOLUME I: DRAFT FINAL REPORT 1. Introduction 2. Development Co-operation Context 3. EC strategy and the logic of EC support 4. Findings 5. Conclusions 6. -

ABSTRACT ICT Integration in Teacher Education

저작자표시-비영리-변경금지 2.0 대한민국 이용자는 아래의 조건을 따르는 경우에 한하여 자유롭게 l 이 저작물을 복제, 배포, 전송, 전시, 공연 및 방송할 수 있습니다. 다음과 같은 조건을 따라야 합니다: 저작자표시. 귀하는 원저작자를 표시하여야 합니다. 비영리. 귀하는 이 저작물을 영리 목적으로 이용할 수 없습니다. 변경금지. 귀하는 이 저작물을 개작, 변형 또는 가공할 수 없습니다. l 귀하는, 이 저작물의 재이용이나 배포의 경우, 이 저작물에 적용된 이용허락조건 을 명확하게 나타내어야 합니다. l 저작권자로부터 별도의 허가를 받으면 이러한 조건들은 적용되지 않습니다. 저작권법에 따른 이용자의 권리는 위의 내용에 의하여 영향을 받지 않습니다. 이것은 이용허락규약(Legal Code)을 이해하기 쉽게 요약한 것입니다. Disclaimer Master’s Thesis of Arts ICT Integration in Teacher Education A Teacher Training Institute Case in Lao PDR 교사교육과 ICT 통합 라오스 교원양성기관 사례를 중심으로 February 2017 Global Education Cooperation Major Graduate School of Education Seoul National University Yikun You ABSTRACT ICT Integration in Teacher Education A Teacher Training Institute Case in Lao PDR Yikun You Global Education Cooperation Major The Graduate School Seoul National University Information and Communication Technology (ICT) integration in education has gained global popularity, yet, not much has been known about how ICT has integrated into teacher education in Lao PDR. This study applies UNESCO’s four stages continuum model and SEAMEO’s ten- dimension framework to make a comprehensive description of the situation of ICT integration in a teacher training institutes in Lao PDR, marking both the achievement and challenges. This study chooses Luang Prabang Teacher Training Colleges (LPB TTC) as the research site. It targets on collecting experience in regard of ICT of the pre-service teachers (PTs) and teacher educators (TEs). -

Phonesay District Agro-Ecosystems Analysis

LSUAFRP Field Report No 2004/05 Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute Draft Report on Phonesay District Agro-ecosystems Analysis Luang Prabang Province Land Management Component - Soils Survey and Land Classification Centre Lao Swedish Upland Agriculture and Forestry Research Programme August, 2004 Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute LSUAFRP Field Report No. 2004/05 Draft Report on Phonesay District Agro-ecosystems Analysis Luang Prabang Province Land Management Component - Soils Survey and Land Classification Centre August 2004 Lao-Swedish Upland Agriculture and Forestry Research Programme Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ...................................................................................1 1.1 INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1 1.2 PARTICIPANTS IN PILOT AEA ACTIVITY ..................................................................................1 1.3 AGRO-ECOSYSTEM ANALYSIS PROCESS ...................................................................................1 1.4 OVERALL PURPOSE AND OBJECTIVES OF AEA.........................................................................2 2 AEA PROCEDURES AND METHODOLOGY ..........................................................................2 2.1 KEY OUTPUTS ...........................................................................................................................2 -

1 Lao People's Democratic Republic Peace Independence Democracy Unity Prosperity Ministry of Health Department of Planning

Lao People’s Democratic Republic Peace Independence Democracy Unity Prosperity Ministry of Health Department of Planning and Cooperation GMS Health Security Project Cross border checkpoint (Points of entry) survey report The department of communicable disease control of the ministry of health conducted the survey of the border checkpoints during the period of June to September 2019. The survey was to implement one of the activities of the annual operation plan 2019 supported by the health security project and funded by the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The overall objectives of the survey were to have the information about the operation and the capacity of the border checkpoints in meeting the core capacity of the International Health Regulation for the public health emergency operation. Specific objectives were to: Map out the location/site of each checkpoint Assess the availability of health facilities, equipment, numbers of health staff and location of health checking counter and SOP Collect the information of traffic volume crossing the border checkpoints Assess the preparedness and response capacity at the PoE See the gaps, constraints and make the recommendation for an improved capacity in disease outbreak control at the border checkpoint I. Border checkpoints in the survey: A totally 27 selected points of entry surveyed which included 4 international airports, 23 ground crossing points and 3 local traditional checkpoints shown in the table below: No. Province District Check point name Shared border Sikhottabong Wattai International -

Simulation of Supply/Demand Balance

The Study on Power Network System Master Plan in Lao PDR Draft Final Report (Stage 3) Simulation of Supply/Demand Balance 17.1. Options for Power Development Plan up to 2030 In order to examine supply reliability and supply-demand balance based on the Lao PDR’s development situation, and considering the development status of the country’s power supply facilities and transmission facilities, a simulation is conducted for 2030. Laos’s power system is examined up to 2030 considering the demand situation in the domestic system and the expansion plans for transmission lines. The northern and central 1 areas are put together to form a Laos NC system, the central 2 a Laos C system, and the southern part an S system. Based on the results of the supply/demand balance simulations, we make recommendations for power plant expansion plans and transmission lines, and for interconnections with neighboring countries. Power Development Plan for Laos’ domestic system up to 2030 1. Power plants for analysis of supply/demand balance in Laos In examining the supply/demand balance for domestic demand in Laos up to 2030, we use the power plan approved by the MEM Minister (see Table 17.1-1). Table 17.1-1 Power Development Plan approved by minister of MEM, including existing plants No Power Plant MW Type COD Province Region 1 Nam Dong 1.00 Run of river 1970 Luangprabang NC 2 Nam Ngum 1 155.00 Reservoir 1971 Vientiane Pro NC 3 Nam Ko 1.50 Run of river 1996 Oudomxay NC 4 Nam Luek 60.00 Reservoir 2000 Saysomboun NC 5 Nam Mang 3 40.00 Reservoir 2004 Vientiane Pro -

Annual Opium Poppy Survey 1999/2000

LAO NATIONAL COMMISSION ON DRUG CONTROL AND SUPERVISION Annual Opium Poppy Survey 1999/2000 With the support of UNDCP – Laos and the Illicit Crops Monitoring Programme. Vientiane, October 2000 Table of contents Summary.......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 4 I. The 2000 National Opium Survey............................................................................. 5 Objectives..................................................................................................................... 5 Methodology................................................................................................................. 5 The Baseline............................................................................................................. 5 The Random Sample................................................................................................ 5 The Interviews and Field Measurement.................................................................... 6 The opium growing farmers interview ....................................................................... 6 The field measurement ............................................................................................. 6 Organisation and Staff.................................................................................................. 7 Training ....................................................................................................................... -

Briefing Paper for the 10Th EU-Laos Human Rights Dialogue

FIDH – International Federation for Human Rights and its member organization Lao Movement for Human Rights (LMHR) Briefing paper for the 10th EU-Laos Human Rights Dialogue 14 June 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 .… Political prisoners remain behind bars 2 .… Failure to cooperate with UN human rights mechanisms 3 .… Third UPR marks a step backward 3 .… Legislative elections fail to meet international standards 5 .… Freedom of expression stifled 6 .… Serious violations of religious freedoms persist 7 .… Negative impact of infrastructure and investment projects 11 .. COVID-19 affects infrastructure projects and their impact 12 .. Dam collapse survivors neglected There has been no improvement in the human rights situation in Laos in 2020-2021. Serious violations of civil and political rights, as well as social, economic, and cultural rights, have continued to occur and have remained unaddressed. This briefing paper provides a summary of key human rights developments during this period. Political prisoners remain behind bars Several individuals who have been imprisoned for the exercise of their right to freedom of opinion and expression remain behind bars. They include: • Ms. Houayheuang Xayabouly, aka Mouay, 32, who has been detained since 12 September 2019, is serving a five-year prison sentence on spurious charges under Article 117 of the Criminal Code (“Propaganda against the Lao People’s Democratic Republic”). Mouay is currently detained in Champasak provincial prison. • Mr. Somphone Phimmasone, 34, Mr. Soukan Chaithad, 37, and Ms. Lodkham Thammavong, approximately 35, who have been detained since March 2016, are serving prison sentences of 20, 16, and 12 years, respectively, on trumped-up charges under Articles 56, 65, and 72 of the Criminal Code. -

Chomphet Brochure Back A3

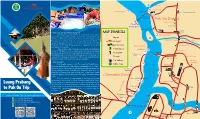

6 Pha Ane Cliff 4 Ban Pak Ou Ban Muang Keo 7 Wat Pak Ou Way to Oudomxay Province 3 Elephant Camp Phone Travel Pak Ou District 5 Ban Huoay Mad Tham Ting Or Pak Ou Cave Indigo farm Manifa Elephant Camp Way to 1. Ban Xang Khong and Ban Xieng Lek MAP SYMBOLS Pak Ou Ban Xang Kong and Ban Xieng Lek are well known villages which 2 Ban Xang Hai produce Posa paper made from mulberry bark and also a style of silk weaving Airport which is very different from others in Laos. You can watch the villagers making 8 Ban Pak Seuang Posa paper (from mulberry bark) and weaving traditional textiles. You’ll see Boat pier Donkhoun Island Ban Viang Sa Vanh this paper around town at the markets, as menus in restaurants and a visit to Ban Xieng Lek and Ban Xang Khong gives you the opportunity to understand Bus Terminal Ban Sen Souk first-hand the way it is made. Ban Muang Kham Where are these villages? 3 kilometers to the north of Luang Prabang Petrol station Wat Khokphap , across the Nam Khan river. These villages can be reached by tuk tuk (though 9 Ban Pha O you will need to cross by the new bridge) and by bicycle (old bridge) or even on Restaurant Boat Terminal foot( bamboo bridge). After crossing the old bridge, turn first left and follow the Wat Nong Sa Keo road as it turns north along the Mekong River. You’ll see craft shops and probably Temple Ban Phon Sai the mulberry paper drying outside in the sun as you approach. -

Report of the 1St Knowledge Capitalization Workshop on Nam Khan Watershed, Lao PDR

Preserving the Natural and Cultural Heritage of the Nam Khan Watershed Report of the 1st Knowledge Capitalization Workshop on Nam Khan Watershed, Lao PDR PAFO office, Luang Prabang, Lao PDR February 4‐5, 2010 Jérémy Ferrand, Jean‐Christophe Castella March 2010 Citation: Ferrand J., Castella J.C. (2010). Report of the 1st Knowledge Capitalization Workshop on Nam Khan Watershed. Eco-Valley Programme, WREO, Luang Prabang, Laos. Contents General background Introduction Introduction to the knowledge capitalization process and expectations for the first workshop The Nam Khan Eco-valley Programme and the role of the knowledge capitalization process The Nam Khan area: a diversity of natures and cultures Plenary presentation and discussion Group discussion: Identifying zones in NK watershed that are homogenous in terms of conservation & development issues Who is doing what, where, in the Nam Khan area Plenary presentation and discussion Group discussion: List the new project, prioritize geographical areas and topic to address What are the issues to be tackled in priority in the Nam Khan watershed? Plenary presentations and discussion Group discussions: towards a management plan to tackle the priority issues in the Nam Khan watershed? From knowledge integration to integrated management of natural resources Experiences from a Regional Park in France Main conclusions and perspectives Appendix 1: List of participants Appendix 2: Agenda of the workshop Appendix 3: Introduction to the knowledge capitalization process Appendix 4: The Nam Khan Eco‐valley Programme Appendix 5: Diversity of natural and human environments in the Nam Khan watershed Appendix 6: Who is doing what, where, in the Nam Khan area Appendix 7: Nam Khan studies and projects profile sheets 2 General background This workshop was the first step of the knowledge capitalization process of the Nam Khan Ecovalley programme. -

Use of Living Aquatic Resources in the Livelihood of Rural People and Fisheries Management in the Nam Ou River

Use of Living Aquatic Resources in the Livelihood of Rural People and Fisheries Management in the Nam Ou River 平成 19 年編入 Country:Laos PHOUSAVANH PHOUVIN Keywords: Aquatic resources, Lao PDR, Ou River, fishery management, fish conservation zone, indigenous fish specie, edible aquatic animal, aquatic plant. Introduction The main ecosystem for living aquatic resources in the north of Lao PDR is the Nam Ou or Ou River and its associated waterways and wetlands, which provide a myriad of habitats for the richness of aquatic life forms in the country. The fisheries ecology of the Nam Ou basin is intimately linked to, and influenced by, the morphological and hydrological characteristics of the basin. One of the main driving forces for fishery ecological processes is the Fig 1. The photo of physical separation of important wet season feeding habitats and dry upstream river in Tay village, season habitats. The fish and other aquatic resources from this Gnot Ou district Phongsaly ecosystem that are not domestically consumed are commercialized province. and generate income for the primary producer as well as for the people involved in fish preservation and marketing. As well as being an important source of income for many rural households, fish and other aquatic products also directly contribute to the food security of the Lao PDR population. The research survey is very important to find out the problems and challenges to further sustainable development in Laos in the areas of water resource management, fisheries and fisheries Fig 2. The photo of management, aquatic resource use and conservation. downstream river in Pak Ou village, Pak Ou district Research Objectives Luangphabang province. -

Lao PDR: Sustainable Rural Infrastructure and Watershed Management Sector Project

Resettlement and Ethnic Group Development Framework Document Stage: Draft Project Number: 50236-002 June 2019 Lao PDR: Sustainable Rural Infrastructure and Watershed Management Sector Project Prepared by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry for the Asian Development Bank. i CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 1 June 2019) Currency unit – kip (KN) KN1.00 = $0.000116 $1.00 = KN8,644 ABBREVIATIONS and ACRONYMS ADB – Asian Development Bank AHH – Affected Household AP – Affected Persons COI – Corridor of Impact DAFO – District Agricultural and Forestry and Office DCO – District Coordination Office DMS – Detailed Measurement Survey DRSC – District Resettlement Committee EA – Executing Agency EGS – Environmental Group Survey EG – Ethnic Group EGP - Ethnic Group Plan EGDF – Ethnic Group Development Framework EGDP – Ethnic Group Development Plan EGF – Ethnic Group Farm work EIRR – Economic Internal Rate of Return EM – Entitlement Matrix EMA – External Monitoring Agency GAP – Gender Action Plan GRM – Grievance Redress Mechanism GMS - Greater Mekong Sub region GRU - Grievance and Redress Units HPN – Houaphan HVC High Value Crops IA – Implementing Agency IOL – Inventory of Losses IPP – Indigenous Peoples Plan LARP – Land Acquisition and Resettlement Plan LECS - Lao Economic and Consumption Survey LFNC Lao Farm work National Consultant LNFC – Lao Front for National Construction LPB – Luang Prabang LRM – Lao Resident Mission LSIS – Lao Social Indicator Survey LWU – Lao Women’s Union MAF – Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry MCH – Mother and Child MONRE -

Socio-Economic Survey and Analysis to Identify Drivers of Forest Changes in Houay Khing and Sop Chia Village Clusters

Socio-economic Survey and Analysis to Identify Drivers of Forest Changes in Houay Khing and Sop Chia Village Clusters, Phonxay District, Luang Prabang January 2012 Vientiane, Lao PDR (left blank) Abbreviation and Acronyms CESVI Cooperazione e Sviluppo (Cooperation and Development) DAFO District Agriculture and Forestry Office GDP Growth Domestic Product GoL Government of Lao PDR GPAR Governance and Public Administration Reforms HH Household HK Houay Khing JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency MAF Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry MI Mekong Institute (Thailand) MoIC Ministry of Industry and Commerce MURC Mitsubishi UFJ Research & Consulting NGPES National Growth and Poverty Eradication NTFP Non-Timber Forest Product PADETC Participatory Development Training Centre PAFO Provincial Agriculture and Forestry Office PAREDD Participatory Land and Forest Management Project for Reducing Deforestation PDR Peoples’ Democratic Republic (Lao) PICO Provincial Industry and Commerce Office REDD+ Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation Plus SC Sop Chia TABI The Agrobiodiversity Initiative ToR Terms of Reference UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization VCA Value Chain Analysis i Table of Contents Abbreviation and Acronyms .................................................................................... i Chapter 1 Scope of the Survey ............................................................................... 1 1.1. Background .........................................................................................................................................