Artists Employ a Composite View of the Human Body, but Show It As Regular in Appearance and in a Variety of Poses and Settings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art List by Year

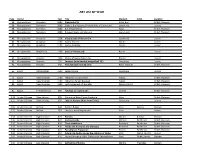

ART LIST BY YEAR Page Period Year Title Medium Artist Location 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Standard of Ur Inlaid Box British Museum 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Stele of the Vultures (Victory Stele of Eannatum) Limestone Louvre 38 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Bull Headed Harp Harp British Museum 39 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Banquet Scene cylinder seal Lapis Lazoli British Museum 40 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2254 Victory Stele of Narum-Sin Sandstone Louvre 42 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Seated Diorite Louvre 43 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Standing Calcite Louvre 44 Mesopotamia Babylonian 1780 Stele of Hammurabi Basalt Louvre 45 Mesopotamia Assyrian 1350 Statue of Queen Napir-Asu Bronze Louvre 46 Mesopotamia Assyrian 750 Lamassu (man headed winged bull 13') Limestone Louvre 48 Mesopotamia Assyrian 640 Ashurbanipal hunting lions Relief Gypsum British Museum 65 Egypt Old Kingdom 2500 Seated Scribe Limestone Louvre 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun hunting fowl Fresco British Museum 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun funery banquet Fresco British Museum 80 Egypt New Kingdom 1300 Last Judgement of Hunefer Papyrus Scroll British Museum 81 Egypt First Millenium 680 Taharqo as a sphinx (2') Granite British Museum 110 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Corinthian Black Figure Amphora Vase British Museum 111 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Lady of Auxerre (Kore from Crete) Limestone Louvre 121 Ancient Greece Archaic 540 Achilles & Ajax Vase Execias Vatican 122 Ancient Greece Archaic 510 Herakles wrestling Antaios Vase Louvre 133 Ancient Greece High -

Writing As Material Practice Substance, Surface and Medium

Writing as Material Practice Substance, surface and medium Edited by Kathryn E. Piquette and Ruth D. Whitehouse Writing as Material Practice: Substance, surface and medium Edited by Kathryn E. Piquette and Ruth D. Whitehouse ]u[ ubiquity press London Published by Ubiquity Press Ltd. Gordon House 29 Gordon Square London WC1H 0PP www.ubiquitypress.com Text © The Authors 2013 First published 2013 Front Cover Illustrations: Top row (from left to right): Flouda (Chapter 8): Mavrospelio ring made of gold. Courtesy Heraklion Archaelogical Museum; Pye (Chapter 16): A Greek and Latin lexicon (1738). Photograph Nick Balaam; Pye (Chapter 16): A silver decadrachm of Syracuse (5th century BC). © Trustees of the British Museum. Middle row (from left to right): Piquette (Chapter 11): A wooden label. Photograph Kathryn E. Piquette, courtesy Ashmolean Museum; Flouda (Chapter 8): Ceramic conical cup. Courtesy Heraklion Archaelogical Museum; Salomon (Chapter 2): Wrapped sticks, Peabody Museum, Harvard. Photograph courtesy of William Conklin. Bottom row (from left to right): Flouda (Chapter 8): Linear A clay tablet. Courtesy Heraklion Archaelogical Museum; Johnston (Chapter 10): Inscribed clay ball. Courtesy of Persepolis Fortification Archive Project, Oriental Institute, University of Chicago; Kidd (Chapter 12): P.Cairo 30961 recto. Photograph Ahmed Amin, Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Back Cover Illustration: Salomon (Chapter 2): 1590 de Murúa manuscript (de Murúa 2004: 124 verso) Printed in the UK by Lightning Source Ltd. ISBN (hardback): 978-1-909188-24-2 ISBN (EPUB): 978-1-909188-25-9 ISBN (PDF): 978-1-909188-26-6 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/bai This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. -

Who's Who in Ancient Egypt

Who’s Who IN ANCIENT EGYPT Available from Routledge worldwide: Who’s Who in Ancient Egypt Michael Rice Who’s Who in the Ancient Near East Gwendolyn Leick Who’s Who in Classical Mythology Michael Grant and John Hazel Who’s Who in World Politics Alan Palmer Who’s Who in Dickens Donald Hawes Who’s Who in Jewish History Joan Comay, new edition revised by Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok Who’s Who in Military History John Keegan and Andrew Wheatcroft Who’s Who in Nazi Germany Robert S.Wistrich Who’s Who in the New Testament Ronald Brownrigg Who’s Who in Non-Classical Mythology Egerton Sykes, new edition revised by Alan Kendall Who’s Who in the Old Testament Joan Comay Who’s Who in Russia since 1900 Martin McCauley Who’s Who in Shakespeare Peter Quennell and Hamish Johnson Who’s Who in World War Two Edited by John Keegan Who’s Who IN ANCIENT EGYPT Michael Rice 0 London and New York First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004. © 1999 Michael Rice The right of Michael Rice to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Core Knowledge Art History Syllabus

Core Knowledge Art History Syllabus This syllabus runs 13 weeks, with 2 sessions per week. The midterm is scheduled for the end of the seventh week. The final exam is slated for last class meeting but might be shifted to an exam period to give the instructor one more class period. Goals: • understanding of the basic terms, facts, and concepts in art history • comprehension of the progress of art as fluid development of a series of styles and trends that overlap and react to each other as well as to historical events • recognition of the basic concepts inherent in each style, and the outstanding exemplars of each Lecture Notes: For each lecture a number of exemplary works of art are listed. In some cases instructors may wish to discuss all of these works; in other cases they may wish to focus on only some of them. Textbooks: It should be possible to teach this course using any one of the five texts listed below as a primary textbook. Cole et al., Art of the Western World Gardner, Art Through the Ages Janson, History of Art, 2 vols. Schneider Adams, Laurie, A History of Western Art Stokstad, Art History, 2 vols. Writing Assignments: A short, descriptive paper on a single work of art or topic would be in order. Syllabus created by the Core Knowledge Foundation 1 https://www.coreknowledge.org/ Use of this Syllabus: This syllabus was created by Bruce Cole, Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts, Indiana University, as part of What Elementary Teachers Need to Know, a teacher education initiative developed by the Core Knowledge Foundation. -

PETRE RADU GURAN OVIDIU OLAR CAMIL ALEXANDRU PÂRVU CÃTÃLIN PAVEL OVIDIU PIETRÃREANU EMILIA PLOSCEANU MIHAELA TIMUª Editor: Irina Vainovski-Mihai

New Europe College Yearbook 2007-2008 MIREL BÃNICÃ CRISTINA CIUCU MARIAN COMAN GABRIEL HORAÞIU DECUBLE PETRE RADU GURAN OVIDIU OLAR CAMIL ALEXANDRU PÂRVU CÃTÃLIN PAVEL OVIDIU PIETRÃREANU EMILIA PLOSCEANU MIHAELA TIMUª Editor: Irina Vainovski-Mihai Copyright – New Europe College ISSN 1584-0298 New Europe College Str. Plantelor 21 023971 Bucharest Romania www.nec.ro; e-mail: [email protected] Tel. (+4) 021.307.99.10, Fax (+4) 021. 327.07.74 PETRE RADU GURAN Born in 1972 in Bucharest Ph.D. in Historical Anthropology, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris (2003) Dissertation: Sainteté royale et pouvoir universel en terre d’Orthodoxie (fin du Moyen Age et début de l’époque moderne) Researcher, Institute for South-East European Studies, Romanian Academy Research scholarship, Österreichisches Ost- und Südosteuropa Institut, Vienna (1993) Masters degree scholarship at the EHESS, Paris (1996-1997) Junior fellow, International Academy of Art and Sciences (1998) DAAD doctoral research scholarship, Ludwig Maximillian University, Munich (2001-2002) Teaching fellow, Princeton University, USA, Program in Hellenic Studies (2004-2006) Attended workshops, conferences and international scientific meetings in Romania, UK, Russia, USA, Italy, Hungary Numerous research papers published both in Romania and abroad Book: Sainteté royale et pouvoir universel en terre d’Orthodoxie. Fin du Moyen Ageet début de l’époque moderne, Paris, Beauchesne, 2007 DOES “POLITICAL THEOLOGY” EXPLAIN THE FORMATION OF ORTHODOXY? Political theology It was largely believed that the perfect blend of Christianity and empire was once and forever offered in the refined recipe of Eusebius of Caesarea for his imperial patron, Constantine.1 Modern scholarship instead has described the encounter between pagan Rome – or not yet Christian Constantinople – and the religion of Christ as a complex and quite long process,2 stretching well over 300 years since the presumed founder of the Christian empire. -

Cyberscribe 162 1

Cyberscribe 162 1 CyberScribe 162 - February 2009 Because some of the themes match images close to the CyberScribe's heart, he intends to start this column by noting the reopening of a gallery in the British Museum...a gallery dedicated to the masterpieces from the tomb of Nebamun. No one really knows who he was, the location of his tomb has been lost, but the plaster panels preserved in London and a few other places have been recleaned, reconserved and are brilliant in their new surroundings. Thee are quite simply, the best and most recognized of all wall art themes from ancient Egypt. They have been off display for years while they underwent intensive work to assure that they are stable, that the paints will not further deteriorate...and now they have their own gallery. The CyberScribe was permitted to see several of the famous panels while they were in storage...and without their protective glass sheets. They are lovely beyond words...and the CyberScribe knows that he will probably never again have that wonderful opportunity. A few of the photos from that day are appended below. In an article from ' The Guardian' (http://www.guardianweekly.co.uk/?page=editorial&id=879&catID=10) (edited for length here), we learn (from the words of Richard Parkinson, a curator in the Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan, at the British Museum): "You might think that after 10 years just focused on these paintings from his funerary chapel, I'd feel very close to Nebamun. But in fact we still know very little about him. -

Chapter 1 Multiple Choice 1. an Important Series of Caves With

Chapter 1 Multiple Choice 1. An important series of caves with paintings from the Paleolithic period is located in ________. a. Italy b. England c. Germany d. France Answer: d 2. Which of the following describes the Venus of Willendorf? a. It is a large Neolithic tomb figure of a woman b. It is a small Paleolithic engraving of a woman c. It is a large Paleolithic rockcut relief of a woman d. It is a small Paleolithic figurine of a woman Answer: d 3. Which of the following animals appears less frequently in the Lascaux cave paintings? a. bison b. horse c. bull d. bear Answer: d 4. In style and concept the mural of the Deer Hunt from Çatal Höyük is a world apart from the wall paintings of the Paleolithic period. Which of the following statements best supports this assertion? a. the domesticated animals depicted b. the subject of the hunt itself c. the regular appearance of the human figure and the coherent groupings d. the combination of men and women depicted Answer: c 5. Which of the following works of art was created first? a. Venus of Willendorf b. Animal frieze at Lascaux c. Apollo 11 Cave plaque d. Chauvet Cave Answer: d 6. One of the suggested purposes for the cave paintings at Altamira is thought to have been: a. decoration for the cave b. insurance for the survival of the herd c. the creation myth of the tribal chief d. a record of the previous season’s kills Answer: b 7. The convention of representing animals' horns in twisted perspective in cave paintings or allowing the viewer to see the head in profile and the horns from the front is termed __________. -

A Study of the Architecture of the Cemetery of El-Hawawish at Akhmim in Upper Egypt in the Old Kingdom

A Study of the Architecture of the Cemetery of El-Hawawish at Akhmim in Upper Egypt in the Old Kingdom * jfe * Elizabeth M. Thompson, B.A., Dip. in Ancient Documentary Studies (Macquarie University) Thesis submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts within Macquarie University, Division of Humanities, School of Ancient History, Sydney. November, 2001 * * * I, Elizabeth M. Thompson, certify that the work presented here has not been submitted for a higher degree to any other university or institution. SUMMARY The thesis examines the architectural features and measurements of the rock hewn tombs in the necropolis of El-Hawawish at Akhmim, the capital o f the ninth province in Upper Egypt and a major administrative centre. The cemetery contains the burials of high and middle rank officials who administered the province in the Old Kingdom from the Fifth to the Eighth Dynasties (c. 2400-2160B.C.). The tombs are examined firstly, to determine whether architectural features could assist in the dating of their owners and secondly, whether certain features and measurements are indicative of the rank of these officials. Comparisons are made with tombs in the Memphite and provincial cemeteries and a study of the various elements of tomb architecture at El-Hawawish showed a chronological development similar to that observed in the tombs of the royal necropoli at Giza and Saqqara. Particular features which were introduced in certain reigns here can be found in what appear to be contemporary tombs at El-Hawawish and other provincial cemeteries. The rank of tomb owners is clearly revealed in the larger or smaller dimensions of chapels and burial chambers, and by the inclusion of certain features. -

Expedice PARIS Obsah

Expedice PARIS Obsah KATEDRÁLA NOTRE-DAME ........................................................................................................................... 8 MĚSTSKÁ RADNICE ........................................................................................................................................10 PYRAMIDA V LOUVRU .................................................................................................................................. 10 SACRÉ-COEUR ................................................................................................................................................. 13 Montmartre ..........................................................................................................................................................14 The Sacred-Heart Basilica of Montmartre ...........................................................................................................14 Čtvrť Le Marais ...................................................................................................................................................15 ČTVRŤ LA DÉFENSE ....................................................................................................................................... 15 Archa obrany - L'Arche de la Défense .................................................................................................................15 GÉODE .............................................................................................................................................................. -

The Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire) Latin

The Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire) Latin Greek 667 BCE: Greek colonists founded Byzantium 324 CE: Constantine refounded the city as Nova Roma or Constantinople The fall of Rome in 476 ended the western half of Portrait of Constantine, ca. the Roman Empire; the eastern half continued as 315–330 CE. Marble, approx. 8’ the Byzantine Empire, with Constantinople as its 6” high. capital. Early Byzantine Art 6-8th c. The emperor Justinian I ruled the Byzantine Empire from 527 until 565. He is significant for his efforts to regain the lost provinces of the Western Roman Empire, his codification of Roman law, and his architectural achievements. Justinian as world conqueror (Barberini Ivory) Detail: Beardless Christ; Justinian on his horse mid-sixth century. Ivory. The Byzantine Empire , ca 600 Theocracy Government by divine guidance or by officials who are regarded as divinely guided. Justinian as world conqueror (Barberini Ivory), mid-sixth century. Ivory, 1’ 1 1/2” X 10 1/2”. Louvre, Paris. In Orthodox Christianity the central article of faith is the Christ blesses equality of the three aspects the emperor of the Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Personificati All other versions of on of Christianity were considered Victory heresies. Personification of Earth Justinian as world conqueror (Barberini Ivory), mid-sixth Barbarians bearing tribute century. Ivory, 1’ 1 1/2” X 10 1/2”. Louvre, Paris. Comparison: Ara Pacis Augustae, Female personification (Tellus; mother earth?), panel from the east facade of the, Rome, Italy, 13–9 BCE. Marble, approx. 5’ 3” high. Comparison: Equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, from Rome, Italy, ca. -

Press Kit Louvre Power Plays

PRESS KIT Power Plays Exhibition September 27, 2017 - July 2, 2018 Petite Galerie du Louvre Press Contact Marion Benaiteau [email protected] Tél. + 33 (0)1 40 20 67 10 / + 33 (0)6 88 42 52 62 1 SOMMAIRE Press Release page 3 The Exhibition Layout page 5 Press Visuals page 7 2 Press release Art and Cultural Education September 27, 2017 – July 2, 2018 Petite Galerie du Louvre Power Plays The Petite Galerie exhibition for 2017–2018 focuses on the connection between art and political power. Governing entails self- presentation as a way of affirming authority, legitimacy and prestige. Thus art in the hands of patrons becomes a propaganda tool; but it can also be a vehicle for protest and subverting the established order. Spanning the period from antiquity up to our own time, forty works from the Musée du Louvre, the Musée National du Château de Pau, the Château de Versailles and the Musée des Beaux-arts de la Ville de Paris illustrate the evolution of the codes behind the representation of political power. The exhibition is divided into four sections: "Princely Roles": The first room presents the king's functions— priest, builder, warrior/protector—as portrayed through different artistic media. Notable examples are Philippe de Champaigne's Louis XIII, Léonard Limosin's enamel Crucifixion Altarpiece, and the Triad of Osorkon II from ancient Egypt. "Legitimacy through Persuasion": The focus in the second Antoine-François Callet, Louis XVI, 1779, oil on canvas, room is on the emblematic figure of Henri IV, initially a king Musée du Château de Versailles © RMN-Grand Palais in search of legitimacy, then a model for the Bourbon heirs (Château de Versailles) / Christophe Fouin from Louis XVI to the Restoration. -

Byzantine Garden Culture

Byzantine Garden Culture Byzantine Garden Culture edited by Antony Littlewood, Henry Maguire, and Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. © 2002 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University Washington, D.C. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Byzantine garden culture / edited by Antony Littlewood, Henry Maguire and Joachim Wolschke- Bulmahn. p. cm. Papers presented at a colloquium in November 1996 at Dumbarton Oaks. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) ISBN 0-88402-280-3 (alk. paper) 1. Gardens, Byzantine—Byzantine Empire—History—Congresses. 2. Byzantine Empire— Civilization—Congresses. I. Littlewood, Antony Robert. II. Maguire, Henry, 1943– III. Wolschke- Bulmahn, Joachim. SB457.547 .B97 2001 712'.09495—dc21 00-060020 To the memory of Robert Browning Contents Preface ix List of Abbreviations xi The Study of Byzantine Gardens: Some Questions and Observations from a Garden Historian 1 Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn The Scholarship of Byzantine Gardens 13 Antony Littlewood Paradise Withdrawn 23 Henry Maguire Byzantine Monastic Horticulture: The Textual Evidence 37 Alice-Mary Talbot Wild Animals in the Byzantine Park 69 Nancy P. Sevcenko Byzantine Gardens and Horticulture in the Late Byzantine Period, 1204–1453: The Secular Sources 87 Costas N. Constantinides Theodore Hyrtakenos’ Description of the Garden of St. Anna and the Ekphrasis of Gardens 105 Mary-Lyon Dolezal and Maria Mavroudi Khpopoii?a: Garden Making and Garden Culture in the Geoponika 159 Robert Rodgers Herbs of the Field and Herbs of the Garden in Byzantine Medicinal Pharmacy 177 John Scarborough The Vienna Dioskorides and Anicia Juliana 189 Leslie Brubaker viii Contents Possible Future Directions 215 Antony Littlewood Bibliography 231 General Index 237 Index of Greek Words 260 Preface It is with great pleasure that we welcome the reader to this, the first volume ever put together on the subject of Byzantine gardens.