Press Kit Louvre Power Plays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Court of Versailles: the Reign of Louis XIV

Court of Versailles: The Reign of Louis XIV BearMUN 2020 Chair: Tarun Sreedhar Crisis Director: Nicole Ru Table of Contents Welcome Letters 2 France before Louis XIV 4 Religious History in France 4 Rise of Calvinism 4 Religious Violence Takes Hold 5 Henry IV and the Edict of Nantes 6 Louis XIII 7 Louis XIII and Huguenot Uprisings 7 Domestic and Foreign Policy before under Louis XIII 9 The Influence of Cardinal Richelieu 9 Early Days of Louis XIV’s Reign (1643-1661) 12 Anne of Austria & Cardinal Jules Mazarin 12 Foreign Policy 12 Internal Unrest 15 Louis XIV Assumes Control 17 Economy 17 Religion 19 Foreign Policy 20 War of Devolution 20 Franco-Dutch War 21 Internal Politics 22 Arts 24 Construction of the Palace of Versailles 24 Current Situation 25 Questions to Consider 26 Character List 31 BearMUN 2020 1 Delegates, My name is Tarun Sreedhar and as your Chair, it's my pleasure to welcome you to the Court of Versailles! Having a great interest in European and political history, I'm eager to observe how the court balances issues regarding the French economy and foreign policy, all the while maintaining a good relationship with the King regardless of in-court politics. About me: I'm double majoring in Computer Science and Business at Cal, with a minor in Public Policy. I've been involved in MUN in both the high school and college circuits for 6 years now. Besides MUN, I'm also involved in tech startup incubation and consulting both on and off-campus. When I'm free, I'm either binging TV (favorite shows are Game of Thrones, House of Cards, and Peaky Blinders) or rooting for the Lakers. -

Sara Fox [email protected] Tel +1 212 636 2680

For Immediate Release May 18, 2012 Contact: Sara Fox [email protected] tel +1 212 636 2680 A MASTERPIECE BY ROMANINO, A REDISCOVERED RUBENS, AND A PAIR OF HUBERT ROBERT PAINTINGS LEAD CHRISTIE’S OLD MASTER PAINTINGS SALE, JUNE 6 Sale Includes Several Stunning Works From Museum Collections, Sold To Benefit Acquisitions Funds GIROLAMO ROMANINO (Brescia 1484/87-1560) Christ Carrying the Cross Estimate: $2,500,000-3,500,000 New York — Christie’s is pleased to announce its summer sale in New York of Old Master Paintings on June 6, 2012, at 5 pm, which primarily consists of works from private collections and institutions that are fresh to the market. The star lot is the 16th-century masterpiece of the Italian High Renaissance, Christ Carrying the Cross (estimate: $2,500,000-3,500,000) by Girolamo Romanino; see separate press release. With nearly 100 works by great French, Italian, Flemish, Dutch and British masters of the 15th through the 19th centuries, the sale includes works by Sir Peter Paul Rubens, Hubert Robert, Jan Breughel I, and his brother Pieter Brueghel II, among others. The auction is expected to achieve in excess of $10 million. 1 The sale is highlighted by several important paintings long hidden away in private collections, such as an oil-on-panel sketch for The Adoration of the Magi (pictured right; estimate: $500,000 - $1,000,000), by Sir Peter Paul Rubens (Siegen, Westphalia 1577- 1640 Antwerp). This unpublished panel comes fresh to market from a private Virginia collection, where it had been in one family for three generations. -

Kings and Courtesans: a Study of the Pictorial Representation of French Royal Mistresses

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2008 Kings and Courtesans: A Study of the Pictorial Representation of French Royal Mistresses Shandy April Lemperle The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Lemperle, Shandy April, "Kings and Courtesans: A Study of the Pictorial Representation of French Royal Mistresses" (2008). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1258. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1258 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KINGS AND COURTESANS: A STUDY OF THE PICTORIAL REPRESENTATION OF FRENCH ROYAL MISTRESSES By Shandy April Lemperlé B.A. The American University of Paris, Paris, France, 2006 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Fine Arts, Art History Option The University of Montana Missoula, MT Spring 2008 Approved by: Dr. David A. Strobel, Dean Graduate School H. Rafael Chacón, Ph.D., Committee Chair Department of Art Valerie Hedquist, Ph.D., Committee Member Department of Art Ione Crummy, Ph.D., Committee Member Department of Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures Lemperlé, Shandy, M.A., Spring 2008 Art History Kings and Courtesans: A Study of the Pictorial Representation of French Royal Mistresses Chairperson: H. -

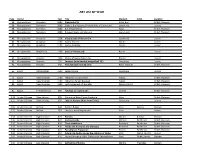

Art List by Year

ART LIST BY YEAR Page Period Year Title Medium Artist Location 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Standard of Ur Inlaid Box British Museum 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Stele of the Vultures (Victory Stele of Eannatum) Limestone Louvre 38 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Bull Headed Harp Harp British Museum 39 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Banquet Scene cylinder seal Lapis Lazoli British Museum 40 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2254 Victory Stele of Narum-Sin Sandstone Louvre 42 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Seated Diorite Louvre 43 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Standing Calcite Louvre 44 Mesopotamia Babylonian 1780 Stele of Hammurabi Basalt Louvre 45 Mesopotamia Assyrian 1350 Statue of Queen Napir-Asu Bronze Louvre 46 Mesopotamia Assyrian 750 Lamassu (man headed winged bull 13') Limestone Louvre 48 Mesopotamia Assyrian 640 Ashurbanipal hunting lions Relief Gypsum British Museum 65 Egypt Old Kingdom 2500 Seated Scribe Limestone Louvre 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun hunting fowl Fresco British Museum 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun funery banquet Fresco British Museum 80 Egypt New Kingdom 1300 Last Judgement of Hunefer Papyrus Scroll British Museum 81 Egypt First Millenium 680 Taharqo as a sphinx (2') Granite British Museum 110 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Corinthian Black Figure Amphora Vase British Museum 111 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Lady of Auxerre (Kore from Crete) Limestone Louvre 121 Ancient Greece Archaic 540 Achilles & Ajax Vase Execias Vatican 122 Ancient Greece Archaic 510 Herakles wrestling Antaios Vase Louvre 133 Ancient Greece High -

History of France Trivia Questions

HISTORY OF FRANCE TRIVIA QUESTIONS ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> In what year did the twelve-year Angevin-Flanders War end? a. 369 b. 1214 c. 1476 d. 1582 2> Which English King invaded Normandy in 1415? a. Henry V b. Charles II c. Edward d. Henry VIII 3> Where was Joan of Arc born? a. England b. Switzerland c. Germany d. France 4> Signed in 843, the "Treaty of Verdun" was an agreement between Charles the Bald and whom? a. Charles the Simple b. Louis the Stammerer c. Louis the German d. Odo 5> Eleanor of Aquitaine was the Queen of France from August 1137 to March 1152. During this time, whom was she married to? a. Louis VI of France b. Philip II of France c. Louis VII of France d. Philip I of France 6> Which country massacred the French garrison in Bruges in 1302? a. Spain b. Germany c. The Country of Flanders d. England 7> What sport did Louis X play? a. Croquet b. Cricket c. Tennis d. Golf 8> How was Charles V known? a. Charles the Wise b. Charles the Short c. Charles the Simple d. Charles the Bald 9> Which French King suffered from mental illness, which earned him the name "The Mad"? a. Benito b. Charles VI c. Louis II d. Phillip I 10> Where is the Basilica of St. Denis? a. Bordeaux b. Toulouse c. Paris d. Tours 11> Who was holding Leonardo da Vinci when he died? a. Eleanor of Aquitaine b. Francis I c. Napoleon d. Cardinal Richelieu 12> Home of Louis XIV, where is the famous Sun Palace located? a. -

Core Knowledge Art History Syllabus

Core Knowledge Art History Syllabus This syllabus runs 13 weeks, with 2 sessions per week. The midterm is scheduled for the end of the seventh week. The final exam is slated for last class meeting but might be shifted to an exam period to give the instructor one more class period. Goals: • understanding of the basic terms, facts, and concepts in art history • comprehension of the progress of art as fluid development of a series of styles and trends that overlap and react to each other as well as to historical events • recognition of the basic concepts inherent in each style, and the outstanding exemplars of each Lecture Notes: For each lecture a number of exemplary works of art are listed. In some cases instructors may wish to discuss all of these works; in other cases they may wish to focus on only some of them. Textbooks: It should be possible to teach this course using any one of the five texts listed below as a primary textbook. Cole et al., Art of the Western World Gardner, Art Through the Ages Janson, History of Art, 2 vols. Schneider Adams, Laurie, A History of Western Art Stokstad, Art History, 2 vols. Writing Assignments: A short, descriptive paper on a single work of art or topic would be in order. Syllabus created by the Core Knowledge Foundation 1 https://www.coreknowledge.org/ Use of this Syllabus: This syllabus was created by Bruce Cole, Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts, Indiana University, as part of What Elementary Teachers Need to Know, a teacher education initiative developed by the Core Knowledge Foundation. -

A Private Mystery: Looking at Philippe De Champaigne’S Annunciation for the Hôtel De Chavigny

chapter 20 A Private Mystery: Looking at Philippe de Champaigne’s Annunciation for the Hôtel de Chavigny Mette Birkedal Bruun Mysteries elude immediate access. The core meaning of the Greek word μυστήριον (mystérion) is something that is hidden, and hence accessible only through some form of initiation or revelation.1 The key Christian mysteries concern the meeting between Heaven and Earth in the Incarnation and the soteriological grace wielded in Christ’s Passion and Resurrection as well as in the sacraments of the Church. Visual representations of the Christian myster- ies strive to capture and convey what is hidden and to express the ineffable in a congruent way. Such representations are produced in historical contexts, and in their aspiration to represent motifs that transcend time and space and indeed embrace time and space, they are marked through and through by their own Sitz-im-Leben. Also, the viewers’ perceptions of such representations are embedded in a historical context. It is the key assumption of this chapter that early modern visual representations of mysteries are seen by human beings whose gaze and understanding are shaped by historical factors.2 We shall approach one such historical gaze. It belongs to a figure who navigated a particular space; who was born into a particular age and class; endowed with a particular set of experiences and aspirations; and informed by a particular devotional horizon. The figure whose gaze we shall approach is Léon Bouthillier, Comte de Chavigny (1608–1652). The mystery in focus is the Annunciation, and the visual representation is the Annunciation painted 1 See Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance, “3466. -

Symbolism and Politics: the Construction of the Louvre, 1660-1667

Symbolism and Politics: The Construction of the Louvre, 1660-1667 by Jeanne Morgan Zarucchi The word palace has come to mean a royal residence, or an edifice of grandeur; in its origins, however, it derives from the Latin palatium, the Palatine Hill upon which Augustus established his imperial residence and erected a temple to Apollo. It is therefore fitting that in the mid-seventeenth century, the young French king hailed as the "new Augustus" should erect new symbols of deific power, undertaking construction on an unprecedented scale to celebrate the Apollonian divinity of his own reign. As the symbols of Apollo are the lyre and the bow, so too were these constructions symbolic of how artistic accomplishment could serve to manifest political power. The project to enlarge the east facade of the Louvre in the early 1660s is a well-known illustration of this form of artistic propaganda, driven by what Orest Ranum has termed "Colbert's unitary conception of politics and culture (Ranum 265)." The Louvre was also to become, however, a political symbol on several other levels, reflecting power struggles among individual artists, the rivalry between France and Italy for artistic dominance, and above all, the intent to secure the king's base of power in the early days of his personal reign. In a plan previously conceived by Cardinal Mazarin as the «grand dessin,» the Louvre was to have been enlarged, embellished, and ultimately joined to the Palais des Tuileries. The demolition of houses standing in the way began in 1657, and in 1660 Mazarin approved a new design submitted by Louis Le Vau. -

War and Culture in the French Empire from Louis XIV to Napoleon

History: Reviews of New Books ISSN: 0361-2759 (Print) 1930-8280 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vhis20 The Military Enlightenment: War and Culture in the French Empire from Louis XIV to Napoleon Jonathan Abel To cite this article: Jonathan Abel (2018) The Military Enlightenment: War and Culture in the French Empire from Louis XIV to Napoleon, History: Reviews of New Books, 46:5, 129-129, DOI: 10.1080/03612759.2018.1489693 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03612759.2018.1489693 Published online: 05 Oct 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 11 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vhis20 September 2018, Volume 46, Number 5 129 Cotta), for it offers a highly different aimed at “propos[ing] and implement[- nationalistic arguments of writers picture of Junger€ ’s Fronterlebnis than ing] a myriad of reforms” (2). This such as Guibert within the that found in the numerous editions of would regenerate the military, allowing Enlightenment mania for classifying his romanticized and selective auto- it to resume its proper place at the apex the martial abilities of states accord- biography, Storm of Steel, first pub- of European militaries. Elements of ing to national character, specific- lished in German in 1920. masculinity, colonial others, and bur- ally, contrasting France with Prussia. geoning ideas of nationhood and citi- The Military Enlightenment is a HOLGER H. HERWIG zenship also manifested in the military valuable addition to the historiography University of Calgary enlightenment and its writers, illustrat- of the Enlightenment. -

PETRE RADU GURAN OVIDIU OLAR CAMIL ALEXANDRU PÂRVU CÃTÃLIN PAVEL OVIDIU PIETRÃREANU EMILIA PLOSCEANU MIHAELA TIMUª Editor: Irina Vainovski-Mihai

New Europe College Yearbook 2007-2008 MIREL BÃNICÃ CRISTINA CIUCU MARIAN COMAN GABRIEL HORAÞIU DECUBLE PETRE RADU GURAN OVIDIU OLAR CAMIL ALEXANDRU PÂRVU CÃTÃLIN PAVEL OVIDIU PIETRÃREANU EMILIA PLOSCEANU MIHAELA TIMUª Editor: Irina Vainovski-Mihai Copyright – New Europe College ISSN 1584-0298 New Europe College Str. Plantelor 21 023971 Bucharest Romania www.nec.ro; e-mail: [email protected] Tel. (+4) 021.307.99.10, Fax (+4) 021. 327.07.74 PETRE RADU GURAN Born in 1972 in Bucharest Ph.D. in Historical Anthropology, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris (2003) Dissertation: Sainteté royale et pouvoir universel en terre d’Orthodoxie (fin du Moyen Age et début de l’époque moderne) Researcher, Institute for South-East European Studies, Romanian Academy Research scholarship, Österreichisches Ost- und Südosteuropa Institut, Vienna (1993) Masters degree scholarship at the EHESS, Paris (1996-1997) Junior fellow, International Academy of Art and Sciences (1998) DAAD doctoral research scholarship, Ludwig Maximillian University, Munich (2001-2002) Teaching fellow, Princeton University, USA, Program in Hellenic Studies (2004-2006) Attended workshops, conferences and international scientific meetings in Romania, UK, Russia, USA, Italy, Hungary Numerous research papers published both in Romania and abroad Book: Sainteté royale et pouvoir universel en terre d’Orthodoxie. Fin du Moyen Ageet début de l’époque moderne, Paris, Beauchesne, 2007 DOES “POLITICAL THEOLOGY” EXPLAIN THE FORMATION OF ORTHODOXY? Political theology It was largely believed that the perfect blend of Christianity and empire was once and forever offered in the refined recipe of Eusebius of Caesarea for his imperial patron, Constantine.1 Modern scholarship instead has described the encounter between pagan Rome – or not yet Christian Constantinople – and the religion of Christ as a complex and quite long process,2 stretching well over 300 years since the presumed founder of the Christian empire. -

Chapter 1 Multiple Choice 1. an Important Series of Caves With

Chapter 1 Multiple Choice 1. An important series of caves with paintings from the Paleolithic period is located in ________. a. Italy b. England c. Germany d. France Answer: d 2. Which of the following describes the Venus of Willendorf? a. It is a large Neolithic tomb figure of a woman b. It is a small Paleolithic engraving of a woman c. It is a large Paleolithic rockcut relief of a woman d. It is a small Paleolithic figurine of a woman Answer: d 3. Which of the following animals appears less frequently in the Lascaux cave paintings? a. bison b. horse c. bull d. bear Answer: d 4. In style and concept the mural of the Deer Hunt from Çatal Höyük is a world apart from the wall paintings of the Paleolithic period. Which of the following statements best supports this assertion? a. the domesticated animals depicted b. the subject of the hunt itself c. the regular appearance of the human figure and the coherent groupings d. the combination of men and women depicted Answer: c 5. Which of the following works of art was created first? a. Venus of Willendorf b. Animal frieze at Lascaux c. Apollo 11 Cave plaque d. Chauvet Cave Answer: d 6. One of the suggested purposes for the cave paintings at Altamira is thought to have been: a. decoration for the cave b. insurance for the survival of the herd c. the creation myth of the tribal chief d. a record of the previous season’s kills Answer: b 7. The convention of representing animals' horns in twisted perspective in cave paintings or allowing the viewer to see the head in profile and the horns from the front is termed __________. -

Biographical Briefing on King Louis XIV

Biographical Briefing on King Louis XIV Directions: The following infonnation will help your group prepare for the press conference in which one of you has been assigned to play King Louis XIV and the rest of you have other roles to play. To prepare for the press conference, each group member reads a section of the handout and leads a discussion of the questions following that section. Louis XIV became King of France in 1643 at the age of 5. Until Louis was 23, Cardinal Mazarin, the head of the French Catholic Church, controlled the government. At that time, France was the most populated and prosperous country in Europe. Wealthy nobles with great estates, who had been powerful for many years, were now being forced to share their power and influence with a new middle class of merchants who were becoming wealthy through international trade. Louis's own grandiose (extravagant) life-style symbolized the grandeur (magnificence) and wealth of his country. At only 5 feet 4 inches in height, Louis was a charismatic leader who built himself a glorious new city named Versailles near Paris. The enormous Palace of Versailles was full of polished mirrors, gleaming chandeliers, and gardens with fountains. Versailles was marveled at throughout Europe and envied by many other kings. He came to be called the "Sun King" because it seemed that his power and influence radiated from Versailles out to the entire world. .~ • What was France like when Louis assumed the throne? '~ • What did Louis' rich life-style symbolize? • Describe Versailles. Louis XIV believed in his right to exercise absolute power over France.