Apotheosis and After Life;

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heracles's Weariness and Apotheosis in Classical Greek Art

Dourado Lopes, Antonio Orlando Heracles's weariness and apotheosis in Classical Greek art Synthesis 2018, vol. 25, nro. 2, e042 Dourado Lopes, A. (2018). Heracles's weariness and apotheosis in Classical Greek art. Synthesis, 25 (2), e042. En Memoria Académica. Disponible en: http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/art_revistas/pr.10707/pr.10707.pdf Información adicional en www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ ARTÍCULO / ARTICLE Synthesis, vol. 25, nº 2, e042, diciembre 2018. ISSN 1851-779X Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. Centro de Estudios Helénicos Heracles's weariness and apotheosis in Classical Greek art Agotamiento físico y apoteosis de Heracles en el arte clásico griego Antonio Orlando Dourado Lopes Universidad Federal de Minas Gerais, Brasil [email protected] Resumen: Este estudio propone una interpretación general de las imágenes realizadas en Grecia, a partir del siglo V a. C. en monedas, joyas, pinturas de vasijas y esculturas, que muestran el agotamiento físico de Heracles y su apoteosis divina. Luego de una extendida consideración de los principales trabajos académicos que abordaron el tema desde finales del siglo XIX, procuro mostrar que la representación iconográfica del agotamiento de Heracles y de su apoteosis da testimonio de la influencia de nuevas concepciones religiosas y filosóficas en su mito, fundamentalmente del pitagorismo, del orfismo y de los cultos mistéricos, así como del fuerte intelectualismo de la Atenas del siglo V a. C. -

The Apotheosis of He#Rakle#S on Olympus and the Mythological Origins of the Olympics

The apotheosis of He#rakle#s on Olympus and the mythological origins of the Olympics The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Nagy, Gregory. 2019.07.12. "The apotheosis of He#rakle#s on Olympus and the mythological origins of the Olympics." Classical Inquiries. http://nrs.harvard.edu/ urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries. Published Version https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/the-apotheosis-of- herakles-on-olympus-and-the-mythological-origins-of-the- olympics/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41364811 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Classical Inquiries Editors: Angelia Hanhardt and Keith Stone Consultant for Images: Jill Curry Robbins Online Consultant: Noel Spencer About Classical Inquiries (CI ) is an online, rapid-publication project of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, devoted to sharing some of the latest thinking on the ancient world with researchers and the general public. While articles archived in DASH represent the original Classical Inquiries posts, CI is intended to be an evolving project, providing a platform for public dialogue between authors and readers. Please visit http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries for the latest version of this article, which may include corrections, updates, or comments and author responses. Additionally, many of the studies published in CI will be incorporated into future CHS pub- lications. -

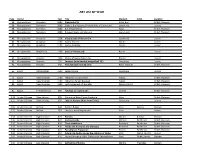

Art List by Year

ART LIST BY YEAR Page Period Year Title Medium Artist Location 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Standard of Ur Inlaid Box British Museum 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Stele of the Vultures (Victory Stele of Eannatum) Limestone Louvre 38 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Bull Headed Harp Harp British Museum 39 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Banquet Scene cylinder seal Lapis Lazoli British Museum 40 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2254 Victory Stele of Narum-Sin Sandstone Louvre 42 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Seated Diorite Louvre 43 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Standing Calcite Louvre 44 Mesopotamia Babylonian 1780 Stele of Hammurabi Basalt Louvre 45 Mesopotamia Assyrian 1350 Statue of Queen Napir-Asu Bronze Louvre 46 Mesopotamia Assyrian 750 Lamassu (man headed winged bull 13') Limestone Louvre 48 Mesopotamia Assyrian 640 Ashurbanipal hunting lions Relief Gypsum British Museum 65 Egypt Old Kingdom 2500 Seated Scribe Limestone Louvre 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun hunting fowl Fresco British Museum 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun funery banquet Fresco British Museum 80 Egypt New Kingdom 1300 Last Judgement of Hunefer Papyrus Scroll British Museum 81 Egypt First Millenium 680 Taharqo as a sphinx (2') Granite British Museum 110 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Corinthian Black Figure Amphora Vase British Museum 111 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Lady of Auxerre (Kore from Crete) Limestone Louvre 121 Ancient Greece Archaic 540 Achilles & Ajax Vase Execias Vatican 122 Ancient Greece Archaic 510 Herakles wrestling Antaios Vase Louvre 133 Ancient Greece High -

Session 5: St. Ignatius to St. Polycarp – Readings

~110 ~120 ~123 98-138 144 154 155 Developments O Gladsome Developments in Persecution & Marcionism 1st attempt at Martyrdom of in the Church Light the Church, Martyrdom Roman Polycarp Didache under Trajan & dominance Hadrian SESSION 5: ST. IGNATIUS TO ST. POLYCARP – READINGS Excerpt from On the Martyrdom of Polycarp Written by Christian witnesses(es) in Smyrna ~156AD Translated by J.B. Lightfoot Abridged by Stephen Tomkins 5. Polycarp’s Vision When he heard about this, the redoubtable Polycarp was not in the least upset, and was happy to stay in the city, but eventually he was persuaded to leave. He went to friends in the nearby country, where as usual he spent the whole time, day and night, in prayer for all people and for the churches throughout the world. Three days before he was arrested, while he was praying, he had a vision of the pillow under his head in flames. He said prophetically to those who were with him, ” I will be burnt alive.” 6. The Betrayal Those who were looking for him were coming near, so he left for another house. They immediately followed him, and when they could not find him, they seized two young men from his own household and tortured them into confession. The sheriff, called Herod, was impatient to bring Polycarp to the stadium, so that he might fulfill his special role, to share the sufferings of Christ, while those who betrayed him would be punished like Judas. 7. The Arrest The police and horsemen came with the young man at suppertime on the Friday with their usual weapons, as if coming out against a robber. -

Vespasian's Apotheosis

VESPASIAN’S APOTHEOSIS Andrew B. Gallia* In the study of the divinization of Roman emperors, a great deal depends upon the sequence of events. According to the model of consecratio proposed by Bickermann, apotheosis was supposed to be accomplished during the deceased emperor’s public funeral, after which the senate acknowledged what had transpired by decreeing appropriate honours for the new divus.1 Contradictory evidence has turned up in the Fasti Ostienses, however, which seem to indicate that both Marciana and Faustina were declared divae before their funerals took place.2 This suggests a shift * Published in The Classical Quarterly 69.1 (2019). 1 E. Bickermann, ‘Die römische Kaiserapotheosie’, in A. Wlosok (ed.), Römischer Kaiserkult (Darmstadt, 1978), 82-121, at 100-106 (= Archiv für ReligionswissenschaftW 27 [1929], 1-31, at 15-19); id., ‘Consecratio’, in W. den Boer (ed.), Le culte des souverains dans l’empire romain. Entretiens Hardt 19 (Geneva, 1973), 1-37, at 13-25. 2 L. Vidman, Fasti Ostienses (Prague, 19822), 48 J 39-43: IIII k. Septembr. | [Marciana Aug]usta excessit divaq(ue) cognominata. | [Eodem die Mati]dia Augusta cognominata. III | [non. Sept. Marc]iana Augusta funere censorio | [elata est.], 49 O 11-14: X[— k. Nov. Fausti]na Aug[usta excessit eodemq(ue) die a] | senatu diva app[ellata et s(enatus) c(onsultum) fact]um fun[ere censorio eam efferendam.] | Ludi et circenses [delati sunt. — i]dus N[ov. Faustina Augusta funere] | censorio elata e[st]. Against this interpretation of the Marciana fragment (as published by A. Degrassi, Inscr. It. 13.1 [1947], 201) see E. -

Collins Magic in the Ancient Greek World.Pdf

9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page i Magic in the Ancient Greek World 9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page ii Blackwell Ancient Religions Ancient religious practice and belief are at once fascinating and alien for twenty-first-century readers. There was no Bible, no creed, no fixed set of beliefs. Rather, ancient religion was characterized by extraordinary diversity in belief and ritual. This distance means that modern readers need a guide to ancient religious experience. Written by experts, the books in this series provide accessible introductions to this central aspect of the ancient world. Published Magic in the Ancient Greek World Derek Collins Religion in the Roman Empire James B. Rives Ancient Greek Religion Jon D. Mikalson Forthcoming Religion of the Roman Republic Christopher McDonough and Lora Holland Death, Burial and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt Steven Snape Ancient Greek Divination Sarah Iles Johnston 9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page iii Magic in the Ancient Greek World Derek Collins 9781405132381_1_pre.qxd 30/10/2007 12:09 Page iv © 2008 by Derek Collins blackwell publishing 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Derek Collins to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Knights 1056 and Little Iliad F2

“Even a woman could carry”: Knights 1056 and Little Iliad F2 In their contest for the love of Demos, Paphlagon boasts of capturing hundreds of Spartan “ravenfish” (at Pylos) and the Sausage Seller replies, καί κε γυνὴ φέροι. That cryptic line goes unanswered and we would not guess its significance were it not for the scholia: it comes from the “Judgment of Arms” in the Little Iliad. On the advice of Nestor, the Achaeans sent out scouts to listen in on the Trojans, thus to discover which of the two contenders for Achilles’ legacy was the more deserving. They overheard two girls arguing over that very issue: one praised Ajax for rescuing the body of Achilles and (at Athena’s prompting) the other responded with the insult: Odysseus fought off the Trojans as Ajax made off with the body, and even a woman could carry a burden if she doesn’t have to fight for it. This version of the Judgment seems, as Martin West described it, “the silliest and most far-fetched,” assuming “[t]he second girl’s aphorism ... is decisive for the award of the arms to Odysseus” (2013: 176). But that way of deciding the issue would also be absurd to the ancient audience. This paper offers a new reconstruction of the episode in line with the workings of archaic justice. In Odyssey 11.547, Odysseus recalls that παῖδες Τρώων “gave judgment” in his favor; the scholiast on that line says it was athetized by Aristarchos as an interpolation from the epic cycle, and scholars have often supposed that it is essentially the same tale that figures in Little Iliad. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Core Knowledge Art History Syllabus

Core Knowledge Art History Syllabus This syllabus runs 13 weeks, with 2 sessions per week. The midterm is scheduled for the end of the seventh week. The final exam is slated for last class meeting but might be shifted to an exam period to give the instructor one more class period. Goals: • understanding of the basic terms, facts, and concepts in art history • comprehension of the progress of art as fluid development of a series of styles and trends that overlap and react to each other as well as to historical events • recognition of the basic concepts inherent in each style, and the outstanding exemplars of each Lecture Notes: For each lecture a number of exemplary works of art are listed. In some cases instructors may wish to discuss all of these works; in other cases they may wish to focus on only some of them. Textbooks: It should be possible to teach this course using any one of the five texts listed below as a primary textbook. Cole et al., Art of the Western World Gardner, Art Through the Ages Janson, History of Art, 2 vols. Schneider Adams, Laurie, A History of Western Art Stokstad, Art History, 2 vols. Writing Assignments: A short, descriptive paper on a single work of art or topic would be in order. Syllabus created by the Core Knowledge Foundation 1 https://www.coreknowledge.org/ Use of this Syllabus: This syllabus was created by Bruce Cole, Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts, Indiana University, as part of What Elementary Teachers Need to Know, a teacher education initiative developed by the Core Knowledge Foundation. -

Augustine's Reconstruction of Martyrdom in Late Antique North Africa Collin S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Louisiana State University Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 Reclaiming martyrdom: Augustine's reconstruction of martyrdom in late antique North Africa Collin S. Garbarino Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Garbarino, Collin S., "Reclaiming martyrdom: Augustine's reconstruction of martyrdom in late antique North Africa" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 3420. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3420 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECLAIMING MARTYRDOM: AUGUSTINE’S RECONSTRUCTION OF MARTYRDOM IN LATE ANTIQUE NORTH AFRICA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Collin S. Garbarino B.A., Louisiana Tech University, 1998 M.Div., The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2005 December 2007 Brevis est dies: longo sermone etiam nos tenere vestram patientiam non debemus (Serm. 274). ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT . v Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 The Development of Martyrdom in Early Christianity . 2 Historiography on Donatism and Martyrdom . 8 Sermons as Sources . -

PETRE RADU GURAN OVIDIU OLAR CAMIL ALEXANDRU PÂRVU CÃTÃLIN PAVEL OVIDIU PIETRÃREANU EMILIA PLOSCEANU MIHAELA TIMUª Editor: Irina Vainovski-Mihai

New Europe College Yearbook 2007-2008 MIREL BÃNICÃ CRISTINA CIUCU MARIAN COMAN GABRIEL HORAÞIU DECUBLE PETRE RADU GURAN OVIDIU OLAR CAMIL ALEXANDRU PÂRVU CÃTÃLIN PAVEL OVIDIU PIETRÃREANU EMILIA PLOSCEANU MIHAELA TIMUª Editor: Irina Vainovski-Mihai Copyright – New Europe College ISSN 1584-0298 New Europe College Str. Plantelor 21 023971 Bucharest Romania www.nec.ro; e-mail: [email protected] Tel. (+4) 021.307.99.10, Fax (+4) 021. 327.07.74 PETRE RADU GURAN Born in 1972 in Bucharest Ph.D. in Historical Anthropology, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris (2003) Dissertation: Sainteté royale et pouvoir universel en terre d’Orthodoxie (fin du Moyen Age et début de l’époque moderne) Researcher, Institute for South-East European Studies, Romanian Academy Research scholarship, Österreichisches Ost- und Südosteuropa Institut, Vienna (1993) Masters degree scholarship at the EHESS, Paris (1996-1997) Junior fellow, International Academy of Art and Sciences (1998) DAAD doctoral research scholarship, Ludwig Maximillian University, Munich (2001-2002) Teaching fellow, Princeton University, USA, Program in Hellenic Studies (2004-2006) Attended workshops, conferences and international scientific meetings in Romania, UK, Russia, USA, Italy, Hungary Numerous research papers published both in Romania and abroad Book: Sainteté royale et pouvoir universel en terre d’Orthodoxie. Fin du Moyen Ageet début de l’époque moderne, Paris, Beauchesne, 2007 DOES “POLITICAL THEOLOGY” EXPLAIN THE FORMATION OF ORTHODOXY? Political theology It was largely believed that the perfect blend of Christianity and empire was once and forever offered in the refined recipe of Eusebius of Caesarea for his imperial patron, Constantine.1 Modern scholarship instead has described the encounter between pagan Rome – or not yet Christian Constantinople – and the religion of Christ as a complex and quite long process,2 stretching well over 300 years since the presumed founder of the Christian empire. -

Major Themes and Motifs in the Dionysiaca

chapter 6 Major Themes and Motifs in the Dionysiaca Fotini Hadjittofi A feature which will immediately strike the first-time reader of Nonnus’ Dionysiaca is the poet’s penchant for creating formulaic scenes or expressions: verses can be repeated verbatim or in a slightly varied form, and passages can be recast several times, with different protagonists and only minor alterations.1 These recurrent scenes and expressions are certainly a manifestation of Nonnus’ aesthetic principle of ποικιλία (variatio),2 and have an obvious role to play in structuring the poem. For example, in looking for unifying threads that would tie together the disparate episodes of the Dionysiaca, scholars have identified a set of close structural parallels between the first and last books of the epic.3 Thus, the narrative proper begins with a rape (of Europa, by Zeus) and ends with a rape (of Aura, by Dionysus). The Typhonomachy, in which Zeus defeats Typhoeus, in Books 1–2 corresponds to the Gigantomachy, in which Dionysus defeats the Giants of Thrace, in Book 48. The tragic narratives of Actaeon (Book 5) and Pentheus (Books 44–46) clearly echo each other. Even though this chapter will often focus on the thematic correspondences between the first and last books (as themes which appear in these narratively privileged positions are likely to be fundamental for the whole poem), it does not aim to explore structural questions, such as how far we can push these particular similarities and to what extent Nonnus was indeed striving for a perfect ring composition.4 My aim is to provide an outline of the most important themes and motifs which recur throughout the entire epic, and which will be studied 1 The formularity of Nonnus’ language will not concern me in this chapter, but see D’Ippolito in this volume.