The Cult of Vesta in the Roman World Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in Criminal Trials in the Julio-Claudian Era

Women in Criminal Trials in the Julio-Claudian Era by Tracy Lynn Deline B.A., University of Saskatchewan, 1994 M.A., University of Saskatchewan, 2001 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Classics) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) September 2009 © Tracy Lynn Deline, 2009 Abstract This study focuses on the intersection of three general areas: elite Roman women, criminal law, and Julio-Claudian politics. Chapter one provides background material on the literary and legal source material used in this study and considers the cases of Augustus’ daughter and granddaughter as a backdrop to the legal and political thinking that follows. The remainder of the dissertation is divided according to women’s roles in criminal trials. Chapter two, encompassing the largest body of evidence, addresses the role of women as defendants, and this chapter is split into three thematic parts that concentrate on charges of adultery, treason, and other crimes. A recurring question is whether the defendants were indicted for reasons specific to them or the indictments were meant to injure their male family members politically. Analysis of these cases reveals that most of the accused women suffered harm without the damage being shared by their male family members. Chapter three considers that a handful of powerful women also filled the role of prosecutor, a role technically denied to them under the law. Resourceful and powerful imperial women like Messalina and Agrippina found ways to use criminal accusations to remove political enemies. Chapter four investigates women in the role of witnesses in criminal trials. -

Succeeding Succession: Cosmic and Earthly Succession B.C.-17 A.D

Publication of this volume has been made possiblej REPEAT PERFORMANCES in partj through the generous support and enduring vision of WARREN G. MOON. Ovidian Repetition and the Metamorphoses Edited by LAUREL FULKERSON and TIM STOVER THE UNIVE RSITY OF WI S CON SIN PRE SS The University of Wisconsin Press 1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059 Contents uwpress.wisc.edu 3 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden London WC2E SLU, United Kingdom eurospanbookstore.com Copyright © 2016 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System Preface Allrights reserved. Except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical vii articles and reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrievalsystem, transmitted in any format or by any means-digital, electronic, Introduction: Echoes of the Past 3 mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise-or conveyed via the LAUREL FULKERSON AND TIM STOVER Internetor a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. Rightsinquiries should be directed to rights@>uwpress.wisc.edu. 1 Nothing like the Sun: Repetition and Representation in Ovid's Phaethon Narrative 26 Printed in the United States of America ANDREW FELDHERR This book may be available in a digital edition. 2 Repeat after Me: The Loves ofVenus and Mars in Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ars amatoria 2 and Metamorphoses 4 47 BARBARA WElDEN BOYD Names: Fulkerson, Laurel, 1972- editor. 1 Stover, Tim, editor. Title: Repeat performances : Ovidian repetition and the Metamorphoses / 3 Ovid's Cycnus and Homer's Achilles Heel edited by Laurel Fulkerson and Tim Stover. PETER HESLIN Other titles: Wisconsin studies in classics. -

00010853-Preview.Pdf

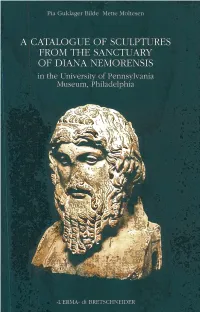

ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI Supplemen turn XXIX A CATALOGUE OF SCULPTURES FROM THE SANCTUARY OF DIANA NEMORENSIS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM, PHILADELPHIA A Catalogue of Sculptures from the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in The University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER ROMAE MMII ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI, SUPPL. XXIX Accademia di Danimarca - Via Omero, 18 - 00197 Rome - Italy Lay-out by the editors © 2002 <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER, Rome PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF GRANTS FROM Knud Højgaards Fond Novo Nordisk Fonden University of Pennsylvania. Museum of archaeology and anthropology A catalogue of sculptures from the sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia / by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen. - Roma: <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER , 2002. - 95 p. : ill. ; 30 cm. (Analecta Romana Instituti Danici. Supplementum ; 29) ISBN 88-8265-211-4 CDD 21. 731.4 1. Sculture in marmo - Collezioni 2. Filadelfia - University of Pennsylvania - Museum of archaeology and anthropology - Cataloghi I. Guldager Bilde, Pia II. Moltesen, Mette The journal ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANICI (ARID) publishes studies within the main range of the Academy's research activities: the arts and humanities, history and archaeology. Intending contributors should get in touch with the editors, who will supply a set of guide- lines and establish a deadline. A print of the article, accompanied y a disk containing the text should be sent to the editors, Accademia di Danimarca, 18 Via Omero, I - 00197 Roma, tel. +39 06 32 65 931, fax +39 06 32 22 717. -

Ritual Cleaning-Up of the City: from the Lupercalia to the Argei*

RITUAL CLEANING-UP OF THE CITY: FROM THE LUPERCALIA TO THE ARGEI* This paper is not an analysis of the fine aspects of ritual, myth and ety- mology. I do not intend to guess the exact meaning of Luperci and Argei, or why the former sacrificed a dog and the latter were bound hand and foot. What I want to examine is the role of the festivals of the Lupercalia and the Argei in the functioning of the Roman community. The best-informed among ancient writers were convinced that these were purification cere- monies. I assume that the ancients knew what they were talking about and propose, first, to establish the nature of the ritual cleanliness of the city, and second, see by what techniques the two festivals achieved that goal. What, in the perception of the Romans themselves, normally made their city unclean? What were the ordinary, repetitive sources of pollution in pre-Imperial Rome, before the concept of the cura Urbis was refined? The answer to this is provided by taboos and restrictions on certain sub- stances, and also certain activities, in the City. First, there is a rule from the Twelve Tables with Cicero’s curiously anachronistic comment: «hominem mortuum», inquit lex in duodecim, «in urbe ne sepelito neve urito», credo vel propter ignis periculum (De leg. II 58). Secondly, we have the edict of the praetor L. Sentius C.f., known from three inscrip- tions dating from the beginning of the first century BC1: L. Sentius C. f. pr(aetor) de sen(atus) sent(entia) loca terminanda coer(avit). -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

THE PONTIFICAL LAW of the ROMAN REPUBLIC by MICHAEL

THE PONTIFICAL LAW OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC by MICHAEL JOSEPH JOHNSON A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Classics written under the direct of T. Corey Brennan and approved by ____________________________ ____________________________ ____________________________ ____________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2007 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Pontifical Law of the Roman Republic by MICHAEL JOSEPH JOHNSON Dissertation Director: T. Corey Brennan This dissertation investigates the guiding principle of arguably the most important religious authority in ancient Rome, the pontifical college. Chapter One introduces the subject and discusses the hypothesis the dissertation will advance. Chapter Two examines the place of the college within Roman law and religion, giving particular attention to disproving several widely held notions about the relationship of the pontifical law to the civil and sacral law. Chapter Three offers the first detailed examination of the duties of the pontifical college as a collective body. I spend the bulk of the chapter analyzing two of the three collegiate duties I identify: the issuing of documents known as decrees and responses and the supervision of the Vestal Virgins. I analyze all decrees and responses from the point of view their content, treating first those that concern dedications, then those on the calendar, and finally those on vows. In doing so my goal is to understand the reasoning behind the decree and the major theological doctrines underpinning it. In documenting the pontifical supervision of Vestal Virgins I focus on the college's actions towards a Vestal accused of losing her chastity. -

The Eternal Fire of Vesta

2016 Ian McElroy All Rights Reserved THE ETERNAL FIRE OF VESTA Roman Cultural Identity and the Legitimacy of Augustus By Ian McElroy A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Classics Written under the direction of Dr. Serena Connolly And approved by ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Eternal Fire of Vesta: Roman Cultural Identity and the Legitimacy of Augustus By Ian McElroy Thesis Director: Dr. Serena Connolly Vesta and the Vestal Virgins represented the very core of Roman cultural identity, and Augustus positioned his public image beside them to augment his political legitimacy. Through analysis of material culture, historiography, and poetry that originated during the principate of Augustus, it becomes clear that each of these sources of evidence contributes to the public image projected by the leader whom Ronald Syme considered to be the first Roman emperor. The Ara Pacis Augustae and the Res Gestae Divi Augustae embody the legacy the Emperor wished to establish, and each of these cultural works contain significant references to the Vestal Virgins. The study of history Livy undertook also emphasized the pathetic plight of Rhea Silvia as she was compelled to become a Vestal. Livy and his contemporary Dionysius of Halicarnassus explored the foundation of the Vestal Order and each writer had his own explanation about how Numa founded it. The Roman poets Virgil, Horace, Ovid, and Tibullus incorporated Vesta and the Vestals into their work in a way that offers further proof of the way Augustus insinuated himself into the fabric of Roman cultural identity by associating his public image with these honored priestesses. -

The Imperial Cult and the Individual

THE IMPERIAL CULT AND THE INDIVIDUAL: THE NEGOTIATION OF AUGUSTUS' PRIVATE WORSHIP DURING HIS LIFETIME AT ROME _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Department of Ancient Mediterranean Studies at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by CLAIRE McGRAW Dr. Dennis Trout, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2019 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled THE IMPERIAL CULT AND THE INDIVIDUAL: THE NEGOTIATION OF AUGUSTUS' PRIVATE WORSHIP DURING HIS LIFETIME AT ROME presented by Claire McGraw, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _______________________________________________ Professor Dennis Trout _______________________________________________ Professor Anatole Mori _______________________________________________ Professor Raymond Marks _______________________________________________ Professor Marcello Mogetta _______________________________________________ Professor Sean Gurd DEDICATION There are many people who deserve to be mentioned here, and I hope I have not forgotten anyone. I must begin with my family, Tom, Michael, Lisa, and Mom. Their love and support throughout this entire process have meant so much to me. I dedicate this project to my Mom especially; I must acknowledge that nearly every good thing I know and good decision I’ve made is because of her. She has (literally and figuratively) pushed me to achieve this dream. Mom has been my rock, my wall to lean upon, every single day. I love you, Mom. Tom, Michael, and Lisa have been the best siblings and sister-in-law. Tom thinks what I do is cool, and that means the world to a little sister. -

The Roman Virtues

An Introduction to the Roman Deities Hunc Notate: The cultural organization, the Roman Republic: Res publica Romana, and authors have produced this text for educational purposes. The Res publica Romana is dedicated to the restoration of ancient Roman culture within the modern day. It is our belief that the Roman virtues must be central to any cultural restoration as they formed the foundation of Romanitas in antiquity and still serve as central to western civilization today. This text is offered free of charge, and we give permission for its use for private purposes. You may not offer this publication for sale or produce a financial gain from its distribution. We invite you to share this document freely online and elsewhere. However, if you do share this document we ask that you do so in an unaltered form and clearly give credit to the Roman Republic: Res publica Romana and provide a link to: www.RomanRepublic.org 1 Roman Republic: Res publica Romana| RomanRepublic.org An Introduction to the Roman Deities The existence of the gods is a helpful thing; so let us believe in them. Let us offer wine and incense on ancient altars. The gods do not live in a state of quiet repose, like sleep. Divine power is all around us - Publius Ovidius Naso Dedicated to anyone who desires to build a relationship with the Gods and Goddesses of Rome and to my friends Publius Iunius Brutus & Lucia Hostilia Scaura 2 Roman Republic: Res publica Romana| RomanRepublic.org An Introduction to the Roman Deities Who are the Roman Gods and Goddesses? Since the prehistoric period humans have pondered the nature of the gods. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/197438 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2019-09-09 and may be subject to change. Studies ANCIENT HISTORY “THE USURPING PRINCEPS”: MAXENTIUS’ IMAGE AND ITS CONSTANTINIAN LEGACY Abstract: This article deals with self-representation of Maxentius, who ruled over Italy and North Africa between 306 and 312. It focuses on the imagery and language that was distributed through coins and portraits during Maxentius’ reign, as well as their reception under Constantine immediately after the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312). It argues that Maxentius revitalized the tradition of a princeps at Rome in order to play upon sentiments of neglect felt at Rome and the time. In coinage, this was most explicitly done through the unprecedented use of the princeps title on the obverse, which initially may Sven Betjes have caused a misunderstanding in the more distant parts of the Maxentian Institute for Historical, Literary and Cultural Studies, realm. The idea of the princeps was captivated in portraiture through visual Radboud University similarities with revered emperors, especially with Trajan, and through [email protected] insertion of Maxentius’ portraits in traditional togate capite velato. When Constantine defeated Maxentius in 312, he took over some of the imagery Sam Heijnen and language that had been employed by his deceased adversary. Constantine, Institute for Historical, Literary and Cultural Studies, too, presented himself as a princeps. -

La Latinità Di Ariccia E La Grecità Di Nemi. Istituzioni Civili E Religiose a Confronto

ANNA PASQUALINI La latinità di Ariccia e la grecità di Nemi. Istituzioni civili e religiose a confronto Il titolo del mio intervento è solo apparentemente contraddittorio. Esso è volto a mettere in relazione due contesti sociali tanto vicini nello spazio quanto distanti per impianto culturale e per funzioni politiche: la città di Ariccia e il lucus Dianius. Del bosco sacro a Diana e della selva che lo circonda si è scritto moltissimo soprattutto da quando esso costituì il fulcro di un’opera straordinaria per ricchezza ed originalità quale quella di Sir James Frazer1 Su Ariccia, invece, come comunità cittadina e sulle sue istituzioni politiche e religiose non si è riflettuto abbastanza2 e, in particolare, queste ultime non sono state messe sufficientemente in relazione con il santuario nemorense. Cercherò, quindi, di svolgere qualche considerazione nella speranza di fornire un piccolo contributo alla definizione degli intricati problemi del territorio aricino. Ariccia, come comunità politica, appare nelle fonti letterarie all’epoca del secondo Tarquinio, il tiranno per eccellenza, spregiatore del Senato e del popolo3. Al Superbo viene attribuita una forte vocazione al controllo politico del Lazio attraverso un’accorta rete di alleanze con i maggiorenti del Lazio, primo fra tutti il più eminente di essi, e cioè Ottavio Mamilio di Tuscolo, che è anche suo genero (Livio I 49); è ancora Tarquinio che, secondo le fonti (Livio I 50), indirizza la politica dei Latini convocando i federati in assemblea presso il lucus sacro a Ferentina4. La scelta del luogo non è casuale. Il bosco sacro è stato localizzato nel territorio di Ariccia, ma esso viene considerato idealmente collegato con il Monte Albano, cioè con il centro sacrale dei Latini, 1 La prima edizione dell’opera, The Golden Bough, risale al 1890. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th.