Colliding Worlds Clean.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multilingual -2010 Resource Directory & Editorial Index 2009

Language | Technology | Business RESOURCE ANNUAL DIRECTORY EDITORIAL ANNUAL INDEX 2009 Real costs of quality software translations People-centric company management 001CoverResourceDirectoryRD10.ind11CoverResourceDirectoryRD10.ind1 1 11/14/10/14/10 99:23:22:23:22 AMAM 002-032-03 AAd-Aboutd-About RD10.inddRD10.indd 2 11/14/10/14/10 99:27:04:27:04 AMAM About the MultiLingual 2010 Resource Directory and Editorial Index 2009 Up Front new year, and new decade, offers an optimistically blank slate, particularly in the times of tightened belts and tightened budgets. The localization industry has never been affected quite the same way as many other sectors, but now that A other sectors begin to tentatively look up the economic curve towards prosperity, we may relax just a bit more also. This eighth annual resource directory and index allows industry professionals and those wanting to expand business access to language-industry companies around the globe. Following tradition, the 2010 Resource Directory (blue tabs) begins this issue, listing compa- nies providing services in a variety of specialties and formats: from language-related technol- ogy to recruitment; from locale-specifi c localization to educational resources; from interpreting to marketing. Next come the editorial pages (red tabs) on timeless localization practice. Henk Boxma enumerates the real costs of quality software translations, and Kevin Fountoukidis offers tips on people-centric company management. The Editorial Index 2009 (gold tabs) provides a helpful reference for MultiLingual issues 101- 108, by author, title, topic and so on, all arranged alphabetically. Then there’s a list of acronyms and abbreviations used throughout the magazine, a glossary of terms, and our list of advertisers for this issue. -

Transperfect Life Sciences

TransPerfect Life Sciences Consolidating Your Language Outsourcing for Global Clinical Development: A Roadmap from End-to-End White Paper Copyright TransPerfect 2009 White Paper: Consolidating Your Language Outsourcing for Global Clinical Development: A Roadmap from End-to-End The role of the language service provider (LSP) in clinical development is In a decentralized vendor environment, each LSP holds a different TM (or changing. Traditionally, translation has been handled reactively—sponsors sometimes no TM at all), which means your organization gets only a small and CROs only turned to their individual LSPs when an immediate need fraction of the potential cost or consistency benefits with each translation. arose. While this method evolved out of necessity, its shortcomings are When multiple providers are involved, divergence in the translated clear: high prices, excessive delays, and poor quality and consistency—all terminology is unavoidable, and without a centralized TM, it’s likely that of which can lead to increased patient risk. Today, however, the world’s best over time identical source content will be translated differently from one LSPs are better positioned than ever to serve clinical development clients provider to the next. However, by consolidating to a single partner or with end-to-end, multidimensional language solutions. a small, trusted group, you can guarantee that all work leverages your organization’s unified TM and glossary, and you can immediately reap the As more and more clinical trials are being conducted internationally, and quality and consistency benefits associated with a managed, core database the clinical development world becomes increasingly globally dispersed, of terminology. it also becomes more competitive. -

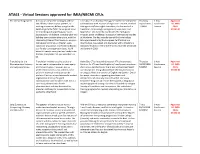

ATA61 - Virtual Sessions Approved for IMIA/NBCMI Ceus

ATA61 - Virtual Sessions approved for IMIA/NBCMI CEUs The Interpreting Games Are you an interpreter looking to add fun Cris Silva, CT is a Brazilian Portuguese conference interpreter Thursday 1-hour Approved. and effective ideas to your practice, or and translator with 20 years of experience. An ATA-certified 10/22/2020 Conference 0.1 IMIA wanting to warm up before you get in the Portuguese to/from English translator, she has worked in 2:00PM Session CEUS. booth or go to the field? Come spend some translation, terminology management, voice-over, and ATA61-01 time working and projecting your voice, localization. She currently coordinates the Portuguese boosting your confidence, standing taller and Program at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies building some positive adrenaline, with the at Monterey. She has recently earned the Terminology Interpreting Games! This hands-on, on-your- Manager credential by the European Certification and feet session will draw on theater, yoga, Qualification Association and graduated with a Master's in voice-over production, and Teaching English Advanced Studies in Interpreter Training from the Université as a Foreign Language techniques. You'll de Genève in 2019. leave this session energized and ready to be the best interpreter that you were born to be. Translating for the Translation involves crossing a cultural Helen Eby, CT is the administrator of ATA's Interpreters Thursday 1-hour Approved. Pharmaceutical Industry barrier and is indispensable to meet equity Division. An ATA-certified English to/from Spanish translator, 10/22/2020 Conference 0.1 IMIA and Language Access and inclusion goals. -

The Role of Revision in English-Spanish Software Localization

THE ROLE OF REVISION IN ENGLISH-SPANISH SOFTWARE LOCALIZATION Graciela Massonnat Mick ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

Resource Directory

Language | Technology | Business RESOURCE ANNUAL DIRECTORY EDITORIAL ANNUAL INDEX 2008 Leveraging your local culture PMs and salespeople: resolving tensions Implementing quality management systems Web globalization and e-business for India 01 Resource Directory RD09.indd 1 1/15/09 1:19:55 PM 02-03 Lemoine-About RD09.indd 2 1/19/09 4:27:21 PM About the MultiLingual 2009 Resource Directory and Editorial Index 2008 Up Front he past year has spurred localization companies and the larger world to re-evaluate the way they do business, which in the long run should ensure that priority is given to diversifying in any market, often resulting in a push towards globalization. Finan- cially, the word is still quite positive in our industry, and we’ve got a healthy resource Tdirectory for 2009 to prove it. Using this resource directory and index, you can easily locate language-industry companies as well as the last year’s content from MultiLingual. This seventh annual publication begins with the Resource Directory (blue tabs), listing companies that develop and use language-related technology along with those providing services in translation, localization, internationalization, website globalization and many other specialties. Next, Tom Edwards explains how to tap into already-available cultural savvy at your company. Also included is advice from Tina Cargile and Erin Vang on managing localization projects and from Betsy Rodriguez on how to streamline any company’s process by creating a quality assurance system. Martin Spethman and Nitish Singh give an overview of India’s e-busi- ness, a rapidly expanding internet market that some predict will have as many as 80 million users by 2010. -

Machine Translation

In the Name of God Translation Services Market and Industry in the Technology-stricken 21st Century Presenter: Ali Beikian Summary of the Workshop The current status of the translation services market The current trends in the translation services industry (an outline of translation services) in the 21st century The most common translation technology tools used in today’s translation services world The challenges which translators face as a result of new technologies Concluding remarks 1. The Current Status of the Translation Market It is exciting times for the translation industry. The value of the language services worldwide was estimated to surpass $37.19 billion in 2014 (CSA Report). CSA has also found that the demand for language services is growing at an annual rate of 6.23%. CSA researchers contend that such a growth is due to several factors, including exchange rates, global competition, and an increase in the use of translation technology. They predict that the translation industry will continue to grow and the market will increase to $47 billion by 2018. 1. The Current Status of the Translation Market The translation industry is estimated to have recently moved from the growth phase to the mature phase of its industry life cycle. IBISWorld asserts that although translation and localization services clients will continue to be price-, service- and quality- conscious, globalization and an increase in immigration will boost demand for language services over the six years ending to 2020 (Translation Services Market Research Report, 2015). There are very few industries that can be considered ‘recession proof’, but in a global market, one that has weathered the storms better than others is the translation services industry. -

Preface of the First Italian Edition

TRANSLATION, ADAPTATION AND MULTILINGUAL EDITING 1 Translation, Adaptation & Multilingual Editing Eurologos Group. Translating and publishing where the languages are spoken. Second edition revised and updated in December 2002 by Franco Troiano 2 Translation, Adaptation & Multilingual Editing Eurologos Group. Translating and publishing where the languages are spoken. Franco Troiano Jacques Permentiers Erik Springael Translation, Adaptation and Multilingual Editing A user's guide to linguistic and multimedia services Foreword by Myriam Salama-Carr, professor at Salford University, UK T.C.G. Editions Brussels 3 Translation, Adaptation & Multilingual Editing Eurologos Group. Translating and publishing where the languages are spoken. Cover illustration: Saint Jerome (patron saint of translators) by Antonello da Messina (1430-1470). National Gallery, London No part of this book may be represented or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the written authorization of the publisher. Copies made for private use or quotations are lawful without consent having been given, provided the names of the authors are mentioned. Telos Communication Group Editions 550 Chaussée de Louvain- 1030 Brussels Brussels 2002 ISBN 2-9600071-0-7 D/1994/6961/1 4 Translation, Adaptation & Multilingual Editing Eurologos Group. Translating and publishing where the languages are spoken. To the unknown and unsung translator 5 Translation, Adaptation & Multilingual Editing Eurologos Group. Translating and publishing where the languages are spoken. Translation, adaptation and multilingual editing This book represents twenty years’ experience in copywriting, translation and multilingual editing. It aims to question the meaning of linguistic quality in the professions of multimedia publishing. Having worked together for over ten years, the authors wished to offer a practical manual to answer the numerous problems and questions (often wrongly formulated) that arise when it comes to translating and printing words; what is more, in various languages. -

In This Issue

April 2010 Volume XXXIX Number 4 The A Publication of the American Translators Association CHRONICLE In this issue: Translating Informed Consent Forms The Language of Cosmetics The Essential Project Manager ATA Professional Liability Insurance Program Administered by Hays Affinity Solutions Program Highlights • Limits ranging from $250,000 to $1,000,000 annual aggregate (higher limits may be available) Join the program that • Affordable Premium: Minimum annual premiums starting from $275 • Loss free credits available offers comprehensive • Experienced claim counsel and risk management services coverage designed • Easy online application and payment process specifically for the Coverage Highlights translation/ • Professional services broadly defined. interpreting • Coverage for bodily injury and/or property. • Coverage for work performed by subcontractors. industry! • Coverage is included for numerical errors or mistranslation of weights and measures for no additional charge. To apply, visit http://ata.haysaffinity.com or call (866) 310-4297 Immediate, no-obligation automated quotes furnished to most applicants! April 2010 Volume XXXIX American Translators Association 225 Reinekers Lane, Suite 590 • Alexandria VA 22314 USA Number 4 Tel: +1-703-683-6100 • Fax: +1-703-683-6122 Contents April 2010 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.atanet.org A Publication of the American Translators Association 12 12 How Do You Do That? By Ewandro Magalhães (Translated from the original Portuguese by Barry Slaughter Olsen) Explore some counterintuitive processes that make simultaneous interpreting possible and learn the answer to a question that has puzzled interpreters for ages—but the answer may surprise you. 15 Translating Informed Consent: Methodological and Ethical Issues By Eric S. Bullington Informed consent is a critical ethical component of modern research involving human subjects. -

Year: 2008 Perspectives

Vol. 17, No. 2, 2008, ISSN 1854-8466. Perspectives Vol. 17, No. 2, 2008 TheWrite Stuff EMWA Executive Committee Journal insights President: TheWrite Stuff is the official publication of the European Medical Julia Forjanic Klapproth Writers Association. It is issued 4 times a year and aims to provide Trilogy Writing & Consulting GmbH EMWA members with relevant, informative and interesting articles and Falkensteiner Strasse 77 news addressing issues relating to the broad arena of medical writing. 60322 Frankfurt am Main, Germany We are open to contributions from anyone whose ideas can complement Tel.: (+49) 69 255 39511, Fax.: (+49) 69 255 39499 these aims, but opinions expressed in individual articles are those of the [email protected] authors and are not necessarily those held by EMWA as an association. Articles or ideas should be submitted to the Editor-in-Chief (see below) Vice President: or another member of the Editorial Board. Helen Baldwin SciNopsis 16 rue Candolle, Subscriptions 83600 Fréjus, France Subscriptions are included in EMWA membership fees. By writing to Tel: (+33) 494 83 90 20, Mobile: (+33) 662 37 91 36 [email protected] non-members can subscribe at an annual [email protected] rate of: • €35 within Europe Treasurer: • €50 outside Europe Wendy Kingdom 1 Red House Road Instructions for contributors East Brent, Highbridge • TheWrite Stuff typically publishes articles of 800–2800 words Somerset, TA9 4RX, UK although longer pieces or those with tables or graphics will be considered. Tel: (+44) 1278 769 214, Fax: (+44) 1278 769 214 [email protected] • All articles are subject to editing and revision by the Editorial Board. -

Curriculum Vitae

[email protected] Mobile: +34 620 88 74 30 [email protected] Phone: +34 965 15 73 61 es.linkedin.com/in/pazgomezpolledo Skype: paz.gomez.polledo CURRICULUM VITAE PAZ GÓMEZ POLLEDO, licensed MBChB, MD.PhD. Biomedical translator, copyeditor, proofreader, writer, linguist consultant, subject-matter expert, post-editor, dubber & subtitler SUMMARY Native from and residing in: Spain Nationality: Spanish Mother tongue: Spanish Translation language combination: English into European and neutral Spanish Working subjects: Medicine, Pharmaceutics, Health Sciences, Life Sciences Tasks: Translation, editing, proofreading, Medical Subject Matter Expert (SME) reviews, 3rd party reviews, Spanish medical writing, Patents, Regulatory Validation of labels and other pharm documents, dubbing and subtitling, Translation and Verification Testing, Machine Translation Post-Editing. Areas of specialization: • Medical journals and conference articles • Oncology, Neuropharmacology, Psycopharmacology, Psychiatry, Neurology, Neurosciences, General Pharmacology, Surgery, Endocrinology, AIDS • Regulatory documentation (clinical protocols, SmPCs, PILs, MSDSs, CRF, SAE/SUSAR, PIS, ICFs, SOAPs, labels validation) • EU terminology (IATE, MedDra, Eur-Lex, EDQM, EMA, AEMPS, etc.) • Linguistic validation of QoL and PROs questionnaires, with cognitive debriefings or focus groups • Medical devices IFU’s • Training and e-learning materials • Patents EXPERIENCED IN TRANSLATION – 34-year experience (See Addendum A-1 to A-5) 16 medical books; around -

Localization Services for the Pharmaceutical Industry

Localization Services for the Pharmaceutical Industry Language Services Solution Brief Pharmaceutical Expertise Supporting end-to-end linguistic solutions for the • Adverse Events full clinical development lifecycle • Case Report Forms With deep knowledge of global pharmaceutical markets and regulations, combined • Clinical Labels with our extensive experience in supporting pharmaceutical companies in achieving • EC Correspondence their objectives, SDL provides language solutions that focus on the unique needs • Informed Consent Forms and challenges of pharmaceutical companies. • Marketing Material • Market Research Material Whether your needs involve clinical trials, regulatory documents for submission • Patient Diaries for Marketing Authorisation (MAA) to EMA, or a product launch, SDL provides • Patient Information Leaflets fast, flexible and cost-effective localization solutions that support regulatory and • Patient Reported Outcomes industry requirements. • Protocol and Synopsis SDL works with 19 of the 20 top life sciences companies, and offers: • Recruitment Material • Legal Contracts • Customized solutions for the pharmaceutical industry • Training Material • Global scalability ...and much more • Expertise in pharmaceutical matters and global regulatory requirements • Qualified and experienced project managers • Specialized subject matter and process expertise • Linguistic validation • Market-leading Translation Management System • Effective, timely communication between multiple users • World class security standards • Support -

Resource Directory Editorial Index 2014

Language | Technology | Business RESOURCE ANNUAL DIRECTORY EDITORIAL ANNUAL INDEX 2014 Where LSPs should go next to better serve their clients What localizing responsibly means today Localization standards reader 5 MultiLingual About the MultiLingual 2015 2015 Resource Directory & Index 2014 Editor-in-Chief, Publisher: Donna Parrish Managing Editor: Katie Botkin Resource Directory and Proofreaders: Bonnie Hagan, Bernie Nova News: Kendra Gray Editorial Index 2014 Production: Darlene Dibble, Doug Jones Cover Graphic Design: Doug Jones Technical Analyst: Curtis Booker Office Manager: Shannon Abromeit Assistant: Chelsea Nova ucky number 13. That’s the count of our annual Index and Resource Circulation: Terri Jadick Directories as of this year. Once again, we have updated and col- Special Projects: Bernie Nova lected together the terms, acronyms and information relevant to our Up Front Advertising Director: Jennifer Del Carlo industry, and we present them here for your perusal. Advertising: Kevin Watson, Bonnie Hagan L First up, the Resource Directory showcases the breadth of the global- Editorial Board ization, internationalization, localization and translation industries. We have Daniel Goldschmidt, Ultan Ó Broin, taken current data on language companies and services, and compiled them Arturo Quintero, Lori Thicke, Jost Zetzsche into listings by category. Whether you’re just getting started as a freelancer Advertising or you’re expanding your internationalization needs on a multinational cor- [email protected] porate level, the contacts listed here should provide a good starting place. The www.multilingual.com/advertising Resource Directory containing all these line listings is marked by handy blue 208-263-8178 tabs in the outermost margins. Subscriptions, back issues, customer service We have also included three new articles with this issue.