The Finland-Swedish Wheel of Migration Identity, Networks and Integration 1976-2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toponymic Guidelines (Pdf)

UNITED NATIONS GROUP OF EXPERTS ON GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES 22nd session, New York, 20-29 April 2004 Item 17 of the provisional agenda TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP EDITORS AND OTHER EDITORS FINLAND Fourth, revised edition 2004* (v. 4.11, April 2021**) * Prepared by Sirkka Paikkala (Research Institute for the Languages of Finland) in collaboration with the Na- tional Land Survey of Finland (Teemu Leskinen) and the Geographical Society of Finland (Kerkko Hakulinen). The 22nd session of UNGEGN in 2004, WP 49. The first edition of this paper, Toponymic Guidelines for International Cartography - Finland, submitted by Mr. A. Rostvik, Norden Division, was presented to the Ninth session of UNGEGN 1981 (WP 37). The second version, Toponymic guidelines for cartography: Finland, prepared by the Onomastic Division of the Finnish Research Centre for Domestic Languages in collabo- ration with the Swedish Language Division and the National Board of Survey, was presented to the 4th UN Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names in 1982 (E/CONF.74/L.41). The second edition, Toponymic Guidelines for Map an Other Editors, pre- paired by the Finnish Research Centre for Domestic Languages together with National Land Survey, was presented to the 17th session of UNGEGNUnited in 1994 (WP 63). The third edi- tion (revised version), prepared by Sirkka Paikkala in collaboration with the National Land Sur- vey of Finland and the Geographical Society of Finland, was presented to the 7th UN Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names (New York, 13-22 January 1998, E/CONF.91/L. 17) ** Editions 4.1 - 4.6 updated by Sirkka Paikkala (Institute for the Languages of Finland) and Teemu Leskinen (National Land Survey of Finland). -

Population Structure 2009

Population 2010 Population Structure 2009 Number of persons aged under 15 in Finland’s population lowest in over 100 years According to Statistics Finland’s statistics on the population structure there were 888,323 persons aged under 15 in Finland’s population at the end of 2009. The number is the lowest since 1895. The size of the population under the age of 15 has been decreasing continuously since 1994. At the end of 1977, there were still one million persons aged under 15 in the Finnish population. The size of the population under the age of 15 was at its largest in 1959 when it was 1.35 million. Number of persons aged under 15 in Finland’s population in 1875–2009 On 31 December 2009, the total population of Finland was 5,351,427 in which 2,625,067 were men and 2,726,360 women. In the course of 2009, Finland’s population grew by 25,113 persons. For the third successive year migration gain from abroad contributed more to the increase of population than natural growth. During 2009, the number of persons aged 65 and over in the population increased by good 18,000 and totalled 910,441 at the end of 2009. The largest age cohort in Finland’s population was persons born in 1948. At the end of 2009, they numbered 82,738. Persons over 100 years of age numbered 566, of whom 82 were men and 484 women. Demographic dependency ratio highest in Etelä-Savo and lowest in Uusimaa The demographic dependency ratio, that is the number of under 15 and over 65-year-olds per 100 working age persons was 50.6 at the end of 2009. -

Language Legislation and Identity in Finland Fennoswedes, the Saami and Signers in Finland’S Society

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI Language Legislation and Identity in Finland Fennoswedes, the Saami and Signers in Finland’s Society Anna Hirvonen 24.4.2017 University of Helsinki Faculty of Law Public International Law Master’s Thesis Advisor: Sahib Singh April 2017 Tiedekunta/Osasto Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos/Institution– Department Oikeustieteellinen Helsingin yliopisto Tekijä/Författare – Author Anna Inkeri Hirvonen Työn nimi / Arbetets titel – Title Language Legislation and Identity in Finland: Fennoswedes, the Saami and Signers in Finland’s Society Oppiaine /Läroämne – Subject Public International Law Työn laji/Arbetets art – Level Aika/Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä/ Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro-Gradu Huhtikuu 2017 74 Tiivistelmä/Referat – Abstract Finland is known for its language legislation which deals with the right to use one’s own language in courts and with public officials. In order to examine just how well the right to use one’s own language actually manifests in Finnish society, I examined the developments of language related rights internationally and in Europe and how those developments manifested in Finland. I also went over Finland’s linguistic history, seeing the developments that have lead us to today when Finland has three separate language act to deal with three different language situations. I analyzed the relevant legislations and by examining the latest language barometer studies, I wanted to find out what the real situation of these language and their identities are. I was also interested in the overall linguistic situation in Finland, which is affected by rising xenophobia and the issues surrounding the ILO 169. -

Swedish-Speaking Population As an Ethnic Group in Finland

SWEDISH-SPEAKING POPULATION AS AN ETHNIC GROUP IN FINLAND Elli Karjalainen" POVZETEK ŠVEDSKO GOVOREČE PREBIVALSTVO KOT ETNIČNA SKUPNOST NA FINSKEM Prispevek obravnava švedsko govoreče prebivalstvo na Finskem, ki izkazuje kot manjši- na, sebi lastne zakonitosti v rasti, populacijski strukturi in geografski razporeditvi. Obra- vnava tudi učinke mešanih zakonov in vključuje tudi vedno aktualne razprave o uporabi finskega jezika na Finskem. Tako v absolutnem kot relativnem smislu upadata število in delež švedskega prebi- valstva na Finskem. Zadnji dostopni podatki govore o 296 840 prebivalcih oziroma 6% deležu Švedov v skupnem številu Finske narodnosti. Švedska poselitev je nadpovprečno zgoščena na jugu in zahodu države. Stalen upad števila članov švedske narodnostne skup- nosti gre pripisati emigraciji, internim migracijskim tokovom, mešanim zakonom in upadu fertilnosti prebivalstva. Tudi starostna struktura švedskega prebivalstva ne govori v prid lastni reprodukciji. Odločilnega pomena je tudi, da so pripadniki švedske narodnosti v povprečju bolj izobraženi kot Finci. Pred kratkim seje zastavilo vprašanje ali je potrebno v finskih šolah ohranjati švedščino kot obvezen učni predmet. Introduction Finland is a bilingual country, with Finnish and Swedish as the official languages of the republic. The Swedish-speaking population is defined as Finnish citizens who live in Finland and speak Swedish as their mother tongue, 'mothertongue' regarded as the language of which the person in question has the best command. Children still too young to speak are registered according to the native tongue of their parents, principally of the mother (Fougstedt 1981: 22). Finland's Swedish-speaking population is here discussed as a minority group: what kind of a population group they form, and how this group differs in population structure from the total population. -

Heikki Har Blick För Österbotten

katternö1 • 2021 EttEtt österbottnisktösterbottniskt magasinmagasin Sjuttonde årgången När Norge erövrade Finland EU-bråk om ”grön” energi Heikki har blick för Österbotten Till kunderna hos Esse Elektro-Kraft, Herrfors, Kronoby Elverk, Nykarleby Kraftverk Viltkameran – så här gör du och Vetelin Energia. katternö – 1 debatt Taxonomiförslag Vilken är den vackraste Tre frågor... Innehåll i fantasivärld platsen i Österbotten? Linus Lindholm NINA LIDFORS, ETT SÄTT ATT ta sig an problemlösning är att klassifi cera problemet Osmo Nissinen, Emelie Wärn, tidigare rektor för i någon av grupperna a) enkla system, b) komplicerade system och c) Ylivieska Larsmo Vasa övningsskola, kaotiska system. Vasa! Det är en levande I Wärnum, Esse, där jag är tillträdde 2009 I enkla system hittas kända och verifi erade orsak/verkan-samband och vacker sommarstad, uppvuxen. Det ligger längs som rektor i Sve- för alla delproblem som ingår i helheten. mycket tack vare närheten Esse å och det är mycket rige för den då nya I kaotiska system fi nns ingen känd kunskap som kan användas, och till havet. Jag besöker Vasa vackert och lugnt där. En Gripsholmsskolan. metodiken är vanligen massvis med tester. I takt med att samband fl era gånger per år och annan bra sak med Wär- Grundarna trodde kan verifi eras, kan nya tester utföras allt mer strukturerat, och på så känner staden mycket väl num är att jag vet vem alla på den fi nländska sätt kan en lösningsmodell för helheten byggas upp. efter att tidigare ha stude- är. Mina föräldrar bor kvar pedagogiken. 30 av Komplicerade system är en blandning av a och c. rat och arbetat där i fyra där och jag återvänder skolans i dag om- Uppvärmningen av vår planet kan kategoriseras som ett komplice- år. -

Julkaisusarjan Nimi

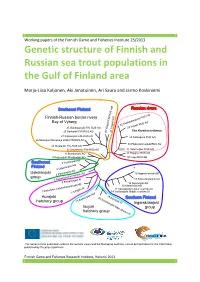

Working papers of the Finnish Game and Fisheries Institute 25/2013 Genetic structure of Finnish and Russian sea trout populations in the Gulf of Finland area Marja-Liisa Koljonen, Aki Janatuinen, Ari Saura and Jarmo Koskiniemi M A S U R O - S A O U Finnish-Russian border rivers N R I o A r u F i p an i l k ka Bay of Vyborg k k O o o A j u o K S j RU o 32 ki a r jo l i Ino i 29 25 Rakkolanjoki FIN-RUS AO V V 1 4 The Karelian Isthmus 23 Santajoki FIN-RUS AO 2 2 27 Kilpeenjoki FIN-RUS AO 28 Notkopuro RUS AO 26 Mustajoki Kananoja 2006 FIN-RUS AO 30 Pikkuvammeljoki RUS AO 26 Mustajoki FIN-RUS AO 22 Urpalanjoki FIN-RUS AO 31 Vammeljoki RUS AO 11 Siuntionjoki AO 33 Rajajoki RUS AO 9 Karjaanjoki Mustionjoki AO 34 Luga RUS AO O njoki A 3 Purila i AO lanjok Uske 5 oki AO Uskelanjoki mionj O 10 Ingarskilanjoki AO 2 Pai oki A rniönj group oki Pe skonj 18 Koskenkylanjoki AI 7 Ki joki AI skarsin 8 Fi 15 Sipoonjoki AO M koski A 12 Mankinjoki AO rtanon Latoka AI 14 Vantaanjoki Lower reaches AI njoki joki Kisko ura 7 1 A 14 Vantaanjoki Middle reaches AI AM oki 1 Aurajoki onj 2 9 K po 0 S ym Es u ijo hatchery group 13 mm ki A an I Ingarskilanjoki jok i M Isojoki ai group n s tre hatchery group am AI The content of the publication reflects the authors views and the Managing Authority cannot be held liable for the information published by the project partners. -

Hamnarna I Österbotten Och Deras Specialisering Pohjanmaan Satamien Erikoistuminen

Activity 3.5 (Port Study, Part I) Hamnarna i Österbotten och deras specialisering Pohjanmaan satamien erikoistuminen www.midnordictc.net SAMMANDRAG Sjötransporterna och hamnarna är av stor betydelse för Österbotten. Det fi nns fyra djuphamnar i Österbotten, de ligger i Jakobstad, Vasa, Kaskö och Kristinestad. Samarbetet mellan hamnarna i Österbotten och deras specialisering borde utvecklas liksom förbindelserna till och från hamnarna både till sjöss och på land. Det primära målet borde vara att de varor som produceras i Österbotten och de varor som importeras hit trans- porteras via de egna hamnarna. Det huvudsakliga målet med detta arbete var att utreda nuläget för de fyra djuphamnarna i Österbotten och deras specialiserings- och samarbetsmöjligheter. Utredningen genomfördes utgående från skriftligt material och fl era intervjuer. I samband med arbetet analyserades också sex olika sce- narion med hjälp av Frisbee-godstrafi kmodellen. De österbottniska hamnarnas ställning är baserad på geografi ska faktorer samt på att de svarar på olika ak- törers behov på ett bra sätt. Samtliga fyra hamnar är redan för närvarande mer eller mindre specialiserade och tillsammans kan de betjäna olika industrisektorer på bred basis. Även samarbetet med Sverige spelar en central roll för utvecklingen av hamnarnas verksamhet. Både i Finland och i Sverige upplevs det som viktigt att utveckla förbindelsen Vasa–Umeå. Tillväxtpotential för Kaskö hamn fi nns enligt godstrafi kmodellen bland an- nat i linjetrafi kens återkomst. Samarbetet mellan hamnarna i Österbotten och på östkusten i Sverige utvecklas också inom ramen för transportkorridorprojekten i öst-västlig riktning (NECL, NLC). Kaskö hamns viktigaste kund är den lokala skogsindustrin. Hamnens styrka är den fungerande hamninfra- strukturen, som lämpar sig väl för hanteringen av skogsindustrins bulkvaror samt ger möjlighet att hantera även andra produkter i fortsättningen. -

District 107 A.Pdf

Club Health Assessment for District 107 A through May 2016 Status Membership Reports LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice No Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Active Activity Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Email ** Report *** Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no report When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater in 3 more than of officers that in 12 within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not have months two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active appears in in brackets in red in red red red indicated Email red Clubs less than two years old 125168 LIETO/ILMATAR 06/19/2015 Active 19 0 16 -16 -45.71% 0 0 0 0 Clubs more than two years old 119850 ÅBO/SKOLAN 06/27/2013 Active 20 1 2 -1 -4.76% 21 2 0 1 59671 ÅLAND/FREJA 06/03/1997 Active 31 2 4 -2 -6.06% 33 11 1 0 41195 ÅLAND/SÖDRA 04/14/1982 Active 30 2 1 1 3.45% 29 34 0 0 20334 AURA 11/07/1968 Active 38 2 1 1 2.70% 37 24 0 4 $536.59 98864 AURA/SISU 03/22/2007 Active 21 2 1 1 5.00% 22 3 0 0 50840 BRÄNDÖ-KUMLINGE 07/03/1990 Active 14 0 0 0 0.00% 14 0 0 32231 DRAGSFJÄRD 05/05/1976 Active 22 0 4 -4 -15.38% 26 15 0 13 20373 HALIKKO/RIKALA 11/06/1958 Active 31 1 1 0 0.00% 31 3 0 0 20339 KAARINA 02/21/1966 Active 39 1 1 0 0.00% 39 15 0 0 32233 KAARINA/CITY 05/05/1976 Active 25 0 5 -5 -16.67% -

Welcome to Ostrobothnia

Welcome to Ostrobothnia A study of the development of integration services for newcomers in the Jakobstad area Malin Winberg Master’s Thesis in Culture and Arts The Degree Programme of Leadership and Service Design Turku 2017 DEGREE THESIS Author: Malin Winberg Degree Master’s degree in Leadership and Service Design Supervisor: Elina Vartama Title: Welcome to Ostrobothnia – A study of the development of integration services for newcomers in the Jakobstad area ________________________________________________________________________ Date 13.11.2017 Number of pages: 79 Appendices: 7 ________________________________________________________________________ Abstract The Integration Port is a newcomer information and support helpdesk based in Jakobstad. It was opened 18.10.2016 as a result of an EU-funded development project running at the Integration Unit in the Jakobstad Region. The aim of the service that is offered by the Integration Port is to support the integration process of all newcomers in the Jakobstad region (Jakobstad, Nykarleby, Kronoby, Pedersöre and Larsmo), regardless of background, by providing them with the help and information that they need. The research for this thesis, in the form of a Service Design study of the Integration Port, includes the following methodologies: observation, workshops, benchmarking, interviews with both customers and stakeholders, brainstorming sessions a survey questionnaire. Tools such as personas, customer journeys and service blueprints have been developed to aid in the design process. The study -

Deltagarlista Catch&Release 2019

Deltagarlista Catch&Release 2019 Team Namn: Ort: största längd Placering Ann: Karvat kråokan Ben-Olof Pitkäkangas Karvat 102 276.000 1 Marcus Kullström Karvat Siben Tran Karvat Hurrit fishing I Jakob Karf Pensala 252.000 2 Peter Nyman Oravais Dånaren Anders Beijar Korsholm 250.000 3 Fredrik Påfs Korsholm Johan Portman Korsholm Peter Ström Korsholm Deltagarlista Singel 2019 Namn: Ort: största kg: Placering Ann: 1 Lehtonen Keijo Smedsby 12.160 2 Kruusma Tanel Pensala 11.600 3 Antus Kjell Oxkangar 10.920 4 Kommonen Fredrik Munsala 8.080 5 Hänninen Anssi Jepua 7.040 6 Blomström Boris Oravais 6.200 7 Kruusma Aare Viro 4.980 8 Pitkäkangas Sami Karvat 4.660 9 Penttinen Jesper Karvat 4.300 10 Granholm Allan Oravais 3.900 11 Järnström Dan-Håkan Oravais 3.880 12 Norrgård Bo Vörå 3.040 13 Hellqvist Stig Oravais 2.320 14 Penttinen Johnny Karvat 2.020 15 Österåker Dan Vörå 1.460 16 Grägg Valter Rejpelt 1.020 17 Eriksson Lars-Erik Oravais 1.000 18 Grägg Leif Vörå 0.000 19 Ekblad Per Nykarleby 0.000 20 Grägg Peter Rejpelt 0.000 21 Kulla Sandra Oravais 0.000 88.580 565.718 Deltagarlista Dubbel 2019 Namn: Ort: största kg: Placering Ann: Stråka Henry Nykarleby 25.840 Vesterlund Patric Nykarleby 5.280 25.840 1 Rosenberg Mikael Vörå 25.760 Solstrand Sven-Erik Kålax 25.760 2 Rintamäki Sten Vörå 4.600 20.700 Rintamäki Hannes Vörå 20.700 3 Koivuniemi Jorma Larsmo 19.580 Myllymäki Kim Jakobstad 19.580 Holmkvist Jonas Lill-Oxkangar 15.880 Granholm Johnny Brudsund 15.880 Ahola Pekka Vähäkyrö 14.660 Ahola Heikki Vaasa 14.660 Taipale Esa Oravais 13.400 Redlig Richard -

Automationsmontör – Elmontör

AUTOMATIONSMONTÖR – ELMONTÖR Grundexamen inom EAB12 – grupphandledare Sandberg Fredrik elbranschen: Ahlvik Victor Pedersöre Automationsmontör/ Blomström Sebastian Jakobstad Bodbacka Kristoffer Nykarleby Elmontör Bolocon John Kristinestad EAA11 – grupphandledare Dahlin Christian Bäck Emil Karleby Björkskog Joni Larsmo Granbacka Niklas Kronoby Enlund Heidi Larsmo Haglund Sebastian Larsmo Gripenberg Benjamin Kronoby Jakas Jakob Vörå Hägg Ronny Pedersöre Kulla Mico Karleby Jansson Martin Närpes Punsar Fredrik Pedersöre Marklund Linus Jakobstad Snellman Jerker Nykarleby Nord Sebastian Jakobstad Stenvall Christoffer Nykarleby Norrgård Alexander Vörå Sundkvist David Larsmo Nygård Daniel Nykarleby Särkijärvi Viktor Larsmo Nygård Rasmus Vörå Ågholm Anton Nykarleby Nynäs Fredrik Jakobstad Pott Alexander Nykarleby EAA13 – grupphandledare Renlund Folke Remesaho Niko Jakobstad Edfelt Michael Larsmo Sund Johnny Jakobstad Enkvist Richard Pedersöre Vertanen Jonas Kronoby Granholm Joel Jakobstad Widjeskog Simon Kronoby Haavisto William Jakobstad Häggblom Jacob Pedersöre EAB11 – grupphandledare Lind Anders Jansson Isak Närpes Björklund Tobias Jakobstad Myhrman Dan Larsmo Broända Emil Nykarleby Nordling Daniel Nykarleby Gädda Robin Jakobstad Norrgård Elina Nykarleby Juselius Filip Nykarleby Nyman Jesper Jakobstad Korkea-Aho Ville Jakobstad Sharma Chintan Jakobstad Kronqvist Joakim Larsmo Smedlund Lukas Jakobstad Libäck Romeo Kronoby Snellman Vegar Jakobstad Lillvik Andreas Nykarleby Stoor Jimmy Nykarleby Luokkala Marcus Karleby Sund Mikael Närpes Niemelä -

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007 FEEFHS Journal Who, What and Why is FEEFHS? The Federation of East European Family History Societies Guest Editor: Kahlile B. Mehr. [email protected] (FEEFHS) was founded in June 1992 by a small dedicated group of Managing Editor: Thomas K. Edlund American and Canadian genealogists with diverse ethnic, religious, and national backgrounds. By the end of that year, eleven societies FEEFHS Executive Council had accepted its concept as founding members. Each year since then FEEFHS has grown in size. FEEFHS now represents nearly two 2006-2007 FEEFHS officers: hundred organizations as members from twenty-four states, five Ca- President: Dave Obee, 4687 Falaise Drive, Victoria, BC V8Y 1B4 nadian provinces, and fourteen countries. It continues to grow. Canada. [email protected] About half of these are genealogy societies, others are multi- 1st Vice-president: Brian J. Lenius. [email protected] purpose societies, surname associations, book or periodical publish- 2nd Vice-president: Lisa A. Alzo ers, archives, libraries, family history centers, online services, insti- 3rd Vice-president: Werner Zoglauer tutions, e-mail genealogy list-servers, heraldry societies, and other Secretary: Kahlile Mehr, 412 South 400 West, Centerville, UT. ethnic, religious, and national groups. FEEFHS includes organiza- [email protected] tions representing all East or Central European groups that have ex- Treasurer: Don Semon. [email protected] isting genealogy societies in North America and a growing group of worldwide organizations and individual members, from novices to Other members of the FEEFHS Executive Council: professionals. Founding Past President: Charles M. Hall, 4874 S. 1710 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84117-5928 Goals and Purposes: Immediate Past President: Irmgard Hein Ellingson, P.O.