(Danio Rerio) Inner Ear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Functions of Vertebrate Ferlins

cells Review Functions of Vertebrate Ferlins Anna V. Bulankina 1 and Sven Thoms 2,* 1 Department of Internal Medicine 1, Goethe University Hospital Frankfurt, 60590 Frankfurt, Germany; [email protected] 2 Department of Child and Adolescent Health, University Medical Center Göttingen, 37075 Göttingen, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 27 January 2020; Accepted: 20 February 2020; Published: 25 February 2020 Abstract: Ferlins are multiple-C2-domain proteins involved in Ca2+-triggered membrane dynamics within the secretory, endocytic and lysosomal pathways. In bony vertebrates there are six ferlin genes encoding, in humans, dysferlin, otoferlin, myoferlin, Fer1L5 and 6 and the long noncoding RNA Fer1L4. Mutations in DYSF (dysferlin) can cause a range of muscle diseases with various clinical manifestations collectively known as dysferlinopathies, including limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2B (LGMD2B) and Miyoshi myopathy. A mutation in MYOF (myoferlin) was linked to a muscular dystrophy accompanied by cardiomyopathy. Mutations in OTOF (otoferlin) can be the cause of nonsyndromic deafness DFNB9. Dysregulated expression of any human ferlin may be associated with development of cancer. This review provides a detailed description of functions of the vertebrate ferlins with a focus on muscle ferlins and discusses the mechanisms leading to disease development. Keywords: dysferlin; myoferlin; otoferlin; C2 domain; calcium-sensor; muscular dystrophy; dysferlinopathy; limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2B (LGMD2B), membrane repair; T-tubule system; DFNB9 1. Introduction Ferlins belong to the superfamily of proteins with multiple C2 domains (MC2D) that share common functions in tethering membrane-bound organelles or recruiting proteins to cellular membranes. Ferlins are described as calcium ions (Ca2+)-sensors for vesicular trafficking capable of sculpturing membranes [1–3]. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Q829X, a Novel Mutation in the Gene Encoding Otoferlin (OTOF), Is Frequently Found in Spanish Patients with Prelingual Non-Syndr

502 LETTER TO JMG J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmg.39.7.502 on 1 July 2002. Downloaded from Q829X, a novel mutation in the gene encoding otoferlin (OTOF), is frequently found in Spanish patients with prelingual non-syndromic hearing loss V Migliosi, S Modamio-Høybjør, M A Moreno-Pelayo, M Rodríguez-Ballesteros, M Villamar, D Tellería, I Menéndez, F Moreno, I del Castillo ............................................................................................................................. J Med Genet 2002;39:502–506 nherited hearing impairment is a highly heterogeneous tial for the application of palliative treatment and special edu- group of disorders with an overall incidence of about 1 in cation. Hence genetic diagnosis and counselling are being I2000 newborns.1 Among them, prelingual, severe hearing increasingly demanded. loss with no other associated clinical feature (non-syndromic) Non-syndromic prelingual deafness is mainly inherited as is by far the most frequent.1 It represents a serious handicap an autosomal recessive trait. To date, 28 different loci for auto- for speech acquisition, and therefore early detection is essen- somal recessive non-syndromic hearing loss have been Table 1 Sequence of primers used for PCR amplification of human OTOF exons Exon Forward primer (5′→3′) Reverse primer (5′→3′) Size (bp) 1 GCAGAGAAGAGAGAGGCGTGTGA AGCTGGCGTCCCTCTGAGACA 203 2 CTGTTAGGACGACTCCCAGGATGA CCAGTGTGTGCCCGCAAGA 239 3 CCCCACGGCTCCTACCTGTTAT GTTGGGAGTGTAGGTCCCCTTTTTA 256 4 GAGTCCTCCCCAAGCAGTCACAG ATTCCCCAGACCACCCCATGT -

A Cell-Based Gene Therapy Approach for Dysferlinopathy Using Sleeping Beauty Transposon

A cell-based gene therapy approach for dysferlinopathy using Sleeping Beauty transposon Inaugural-Dissertation to obtain the academic degree Doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) submitted to the Department of Biology, Chemistry and Pharmacy of Freie Universität Berlin by HELENA ESCOBAR FERNÁNDEZ from León, Spain August 2015 This work was prepared from October 2011 to July 2015 under the supervision of Dr. Zsuzsanna Izsvák (Max-Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, Berlin, Germany) and Prof. Simone Spuler (Experimental and Clinical Research Center, Berlin, Germany). All the experiments were conducted in the laboratories of Dr. Izsvák and Prof. Spuler. 1st reviewer: Prof. Dr. med. Simone Spuler Institute for Chemistry and Biochemistry Department of Biology, Chemistry and Pharmacy Freie Universität, Berlin and Department of Muscle Sciences and University Outpatient Clinic for Muscle Disorders Experimental and Clinical Research Center, Berlin 2nd reviewer: Prof. Dr. Sigmar Stricker Institute for Chemistry and Biochemistry Department of Biology, Chemistry and Pharmacy Freie Universität, Berlin and Development and Disease Group Max Planck Institute of Molecular Genetics, Berlin Date of Defense: November 18th, 2015 Preface The experiments with human muscle fiber fragments were done in collaboration with Dr. Andreas Marg, from the laboratory of Prof. Simone Spuler. Dr. Marg performed the isolation of human fiber fragments and the full characterization of the fiber fragment culture model. I performed the mouse irradiation and transplantation of human fiber fragments into mice. Dr. Marg also performed the mouse irradiation and the analysis of all grafted muscles. i ii Acknowledgements First of all, I want to thank Dr. Zsuzsanna Izsvák for supervising this work and giving me opportunity to carry out my PhD in her laboratory. -

Fera Is a Membrane-Associating Four-Helix Bundle

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN FerA is a Membrane-Associating Four-Helix Bundle Domain in the Ferlin Family of Membrane-Fusion Received: 4 March 2018 Accepted: 4 July 2018 Proteins Published: xx xx xxxx Faraz M. Harsini1, Sukanya Chebrolu1, Kerry L. Fuson1, Mark A. White 2, Anne M. Rice3 & R. Bryan Sutton 1,4 Ferlin proteins participate in such diverse biological events as vesicle fusion in C. elegans, fusion of myoblast membranes to form myotubes, Ca2+-sensing during exocytosis in the hair cells of the inner ear, and Ca2+-dependent membrane repair in skeletal muscle cells. Ferlins are Ca2+-dependent, phospholipid-binding, multi-C2 domain-containing proteins with a single transmembrane helix that spans a vesicle membrane. The overall domain composition of the ferlins resembles the proteins involved in exocytosis; therefore, it is thought that they participate in membrane fusion at some level. But if ferlins do fuse membranes, then they are distinct from other known fusion proteins. Here we show that the central FerA domain from dysferlin, myoferlin, and otoferlin is a novel four-helix bundle fold with its own Ca2+-dependent phospholipid-binding activity. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), spectroscopic, and thermodynamic analysis of the dysferlin, myoferlin, and otoferlin FerA domains, in addition to clinically-defned dysferlin FerA mutations, suggests that the FerA domain interacts with the membrane and that this interaction is enhanced by the presence of Ca2+. Ferlins are a relatively new class of large, multi-domain, type II transmembrane proteins that have been implicated in a wide variety of biological functions centered on membrane fusion events. -

A Hair Bundle Proteomics Approach to Discovering Actin Regulatory Proteins in Inner Ear Stereocilia

-r- A Hair Bundle Proteomics Approach to Discovering Actin Regulatory Proteins in Inner Ear Stereocilia by Anthony Wei Peng SEP 17 2009 B.S. Electrical and Computer Engineering LIBRARIES Cornell University, 1999 SUBMITTED TO THE HARVARD-MIT DIVISION OF HEALTH SCIENCES AND TECHNOLOGY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SPEECH AND HEARING BIOSCIENCES AND TECHNOLOGY AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ARCHIVES JUNE 2009 02009 Anthony Wei Peng. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies o this the is document in whole or in art in any medium nov know or ereafter created. Signature of Author: I Mr=--. r IT Division of Health Sciences and Technology May 1,2009 Certified by: I/ - I / o v Stefan Heller, PhD Associate Professor of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery Stanford University ---- .. Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: -- Ram Sasisekharan, PhD Director, Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology Edward Hood Taplin Professor of Health Sciences & Technology and Biological Engineering. ---- q- ~ r This page is intentionally left blank. I~~riU~...I~ ~-- -pyyur~. _ A Hair Bundle Proteomics Approach to Discovering Actin Regulatory Proteins in Inner Ear Stereocilia by Anthony Wei Peng B.S. Electrical and Computer Engineering, Cornell University, 1999 Submitted to the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Science and Technology on May 7, 2009 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Speech and Hearing Bioscience and Technology Abstract Because there is little knowledge in the areas of stereocilia development, maintenance, and function in the hearing system, I decided to pursue a proteomics-based approach to discover proteins that play a role in stereocilia function. -

What's Hot About Otoferlin

Published online: November 7, 2016 News & Views What’s hot about otoferlin Karen B Avraham Mutations in the otoferlin (OTOF) gene problems worsen upon exposure to heat, otoferlin itself had not been characterized, lead to profound hearing loss in humans. such as a fever. other than by finding sequence homologies Interestingly, a number of missense Otoferlin is a member of the FER-1 family with the spermatogenesis factor FER-1 in otoferlin mutations cause hearing defects of transmembrane proteins distinguished by C. elegans. Eventually, a nonsense mutation but only at higher body temperature, and C2 domains that are also found in synapto- was identified in several families. Subse- the reasons for this have been elusive tagmin, PKC, and PLC isoforms. It binds quent genomic analysis led to the discovery until now. A study published in this issue calcium and membranes and triggers the of both long and short isoforms of OTOF of The EMBO Journal (Strenzke et al, 2016) fusion of neurotransmitter-filled vesicles and, based on a new mutation found in a adds insight into the underlying mecha- with the plasma membrane, presumably in southwestern Indian family, the long nisms for this heat-dependent hearing conjunction with a molecular machinery isoform was deemed essential for inner ear loss. that remains elusive (Roux et al, 2006; function (Yasunaga et al, 2000). Johnson & Chapman, 2010). An article in Mutations in OTOF have since been See also: N Strenzke et al (December this issue of The EMBO Journal also reports found to cause profound sensorineural hear- 2016) and C Vogl et al (December 2016) on the mechanism of membrane insertion of ing loss in patients in many parts of the otoferlin and shows that this is mediated via world, including Spain, Columbia, Argen- magine lying in bed with a fever, tossing, the tail-anchored protein insertion pathway tina, and the Middle East (Adato et al, 2000; and turning, trying to find a comfortable TRC40 (Vogl et al, 2016). -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2003/0198970 A1 Roberts (43) Pub

US 2003O19897OA1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2003/0198970 A1 Roberts (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 23, 2003 (54) GENOSTICS clinical trials on groups or cohorts of patients. This group data is used to derive a Standardised method of treatment (75) Inventor: Gareth Wyn Roberts, Cambs (GB) which is Subsequently applied on an individual basis. There is considerable evidence that a significant factor underlying Correspondence Address: the individual variability in response to disease, therapy and FINNEGAN, HENDERSON, FARABOW, prognosis lies in a person's genetic make-up. There have GARRETT & DUNNER been numerous examples relating that polymorphisms LLP within a given gene can alter the functionality of the protein 1300 ISTREET, NW encoded by that gene thus leading to a variable physiological WASHINGTON, DC 20005 (US) response. In order to bring about the integration of genomics into medical practice and enable design and building of a (73) Assignee: GENOSTIC PHARMA LIMITED technology platform which will enable the everyday practice (21) Appl. No.: 10/206,568 of molecular medicine a way must be invented for the DNA Sequence data to be aligned with the identification of genes (22) Filed: Jul. 29, 2002 central to the induction, development, progression and out come of disease or physiological States of interest. Accord Related U.S. Application Data ing to the invention, the number of genes and their configu rations (mutations and polymorphisms) needed to be (63) Continuation of application No. 09/325,123, filed on identified in order to provide critical clinical information Jun. 3, 1999, now abandoned. concerning individual prognosis is considerably less than the 100,000 thought to comprise the human genome. -

Topics Symposia

Abstracts Topics Symposia Symposia S_1 Structural variation S 1 Structural variation S 2 Low risk cancer genes S1_01 S 3 Transgeneration effects and Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Consequences of Genomic Disor- epigenetic programming ders. Implementation of array CGH in Genetic Diagnostics. The Baylor S 4 Ciliopathies Experience S 5 Systems biology Pawel Stankiewicz S 6 Molecular processes in meiosis Dept. of Molecular & Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Hous- ton, TX, USA Genomic disorders are a group of human genetic diseases caused by Selected Presentations DNA rearrangements, ranging in size from an average exon (~100 bp) to megabases and affecting dosage sensitive genes. Three major mo- lecular mechanisms: non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR), Workshops non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), and the fork stalling and tem- W 1 Clinical genetics plate switching (FoSTeS)/microhomology-mediated breakage-induced W 2 Molecular basis of disease I repair (MMBIR) have been described as causative for the vast majority W 3 Cancer genetics of genomic disorders. Recurrent rearrangements are typically mediated W 4 Molecular basis of disease II by NAHR between low-copy repeats that are usually >10 kb in size with >97% DNA sequence identity. Nonrecurrent CNVs have been found to W 5 Imprinting be formed by NAHR between highly homologous repetitive elements W 6 Genomics technology / bioinformatics (e.g. Alu, LINE) and more often by NHEJ and FoSTeS/MMBIR stimu- W 7 Complex diseases lated, but not mediated, by genomic architectural features. Further- W 8 Cytogenetics / prenatal genetics more, simple repeating DNA sequences that have a potential of adopt- ing non-B DNA conformations (e.g. -

Supplemental Figure 1: Immunoelectron Microscopy of Ribeye on the Harvested Sucrose Pellet from the Gradient Centrifugation Shown in Multiple Panels

Supplemental Figure 1: Immunoelectron microscopy of ribeye on the harvested sucrose pellet from the gradient centrifugation shown in multiple panels. Supplemental Figure 2: Immunoelectron microscopy of VAMP2 on the harvested 200-400 mM sucrose interface sample shown in multiple panels. Supplemental Figure 3: A. Western blots indicate the immunoprecipitation of ribeye and CtBP2 with the CtBP2 antibody. Also coimmunoprecipitation of CtBP1, actin, myosin 9H, spectrin and α-tubulin is shown. B. Western blots indicate the immunoprecipitation of only ribeye with the AD antibody and the coimmunoprecipitation of PRPF39 is indicated. Supplemental Figure 4. Colocalization of ribeye with various presynaptic proteins. The labeling of individual proteins is presented in grayscale and merged panels are depicted in color. Double-labeling with ribeye-specific antiserum reveals the localization with respect to synaptic ribbons of SNARE proteins such as syntaxin 1 (A-C), SNAP25 (D-F), VAMP2 (G-I), syntaxin 6 (J-L), SNAP23 (M-O), VAMP7 (P-R), VAP-33 (S-U); SNARE dissociation molecules such as α-SNAP, β-SNAP (V-X), NSF (Y-A′); hair-cell specific proteins such as glutamate receptors 2 and 3 (GluR2 and GluR3) (B′-D′), glutamate transporter vGluT3 (E′-G′), hair-cell specific Ca2+ channel Cav1.3 (H′-J′), calcium sensor otoferlin (K′-M′); and other synaptic proteins such as rabphilin (N′-P′), munc 18 (Q′-S′), and synapsin (T′-V′). Supplemental Figure 5. Colocalization of ribeye with endocytotic and vesicle- trafficking proteins. The labeling of individual proteins is presented in grayscale and merged panels are depicted in color. Double-labeling with ribeye-specific antiserum reveals the localization of the endocytic proteins clathrin (A-C), dynamin (D-F), SCAMP1 (G-I) and endophilin (J-L) and of the trafficking proteins Sec13 (M-O), β-COP (P-R), VCP (S-U), and GAPDH (V-X) with respect to synaptic ribbons. -

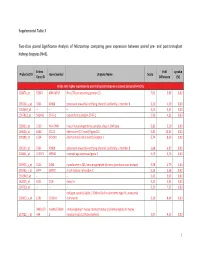

Supplemental Table 3 Two-Class Paired Significance Analysis of Microarrays Comparing Gene Expression Between Paired

Supplemental Table 3 Two‐class paired Significance Analysis of Microarrays comparing gene expression between paired pre‐ and post‐transplant kidneys biopsies (N=8). Entrez Fold q‐value Probe Set ID Gene Symbol Unigene Name Score Gene ID Difference (%) Probe sets higher expressed in post‐transplant biopsies in paired analysis (N=1871) 218870_at 55843 ARHGAP15 Rho GTPase activating protein 15 7,01 3,99 0,00 205304_s_at 3764 KCNJ8 potassium inwardly‐rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 8 6,30 4,50 0,00 1563649_at ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 6,24 3,51 0,00 1567913_at 541466 CT45‐1 cancer/testis antigen CT45‐1 5,90 4,21 0,00 203932_at 3109 HLA‐DMB major histocompatibility complex, class II, DM beta 5,83 3,20 0,00 204606_at 6366 CCL21 chemokine (C‐C motif) ligand 21 5,82 10,42 0,00 205898_at 1524 CX3CR1 chemokine (C‐X3‐C motif) receptor 1 5,74 8,50 0,00 205303_at 3764 KCNJ8 potassium inwardly‐rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 8 5,68 6,87 0,00 226841_at 219972 MPEG1 macrophage expressed gene 1 5,59 3,76 0,00 203923_s_at 1536 CYBB cytochrome b‐245, beta polypeptide (chronic granulomatous disease) 5,58 4,70 0,00 210135_s_at 6474 SHOX2 short stature homeobox 2 5,53 5,58 0,00 1562642_at ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 5,42 5,03 0,00 242605_at 1634 DCN decorin 5,23 3,92 0,00 228750_at ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 5,21 7,22 0,00 collagen, type III, alpha 1 (Ehlers‐Danlos syndrome type IV, autosomal 201852_x_at 1281 COL3A1 dominant) 5,10 8,46 0,00 3493///3 IGHA1///IGHA immunoglobulin heavy constant alpha 1///immunoglobulin heavy 217022_s_at 494 2 constant alpha 2 (A2m marker) 5,07 9,53 0,00 1 202311_s_at -

Autocrine IFN Signaling Inducing Profibrotic Fibroblast Responses by a Synthetic TLR3 Ligand Mitigates

Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/ by guest on September 28, 2021 Inducing is online at: average * The Journal of Immunology published online 16 August 2013 from submission to initial decision 4 weeks from acceptance to publication http://www.jimmunol.org/content/early/2013/08/16/jimmun ol.1300376 A Synthetic TLR3 Ligand Mitigates Profibrotic Fibroblast Responses by Autocrine IFN Signaling Feng Fang, Kohtaro Ooka, Xiaoyong Sun, Ruchi Shah, Swati Bhattacharyya, Jun Wei and John Varga J Immunol Submit online. Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists ? is published twice each month by http://jimmunol.org/subscription Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2013/08/20/jimmunol.130037 6.DC1 Information about subscribing to The JI No Triage! Fast Publication! Rapid Reviews! 30 days* Why • • • Material Permissions Email Alerts Subscription Supplementary The Journal of Immunology The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2013 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. This information is current as of September 28, 2021. Published August 16, 2013, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1300376 The Journal of Immunology A Synthetic TLR3 Ligand Mitigates Profibrotic Fibroblast Responses by Inducing Autocrine IFN Signaling Feng Fang,* Kohtaro Ooka,* Xiaoyong Sun,† Ruchi Shah,* Swati Bhattacharyya,* Jun Wei,* and John Varga* Activation of TLR3 by exogenous microbial ligands or endogenous injury-associated ligands leads to production of type I IFN.