The Impossible Partition of Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf | 702.21 Kb

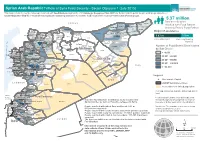

Syrian Arab Republic: Whole of Syria Food Security - Sector Objective 1 (July 2015) This map reflects the number of people reached with Food Baskets against the 2015 Strategic Response Plan (SRP) for Syrian Arab Republic as part of Strategic Objective 2 Sector Objective 1(SO 1) : Provide life-saving and life sustaining assistance to meet the food needs of the most vulnerable crisis affected groups. 5.37 million Total beneficiaries T u rr kk e yy Al Malika Jawadiyah E reached with Food Basket Amuda Quamishli Qahtaniyyeh Darbasiyah (monthly Family Food Ration) Ain al Arab Ya'robiyah Lower Shyookh Bulbul Jarablus Raju Ghandorah Tal Hmis Origin of assistance Sharan Tell Abiad Be'r Al-Hulo Al-Wardeyyeh Ar-Ra'ee Ras Al Ain Ma'btali A'zazSuran Tal Tamer Menbij Al-Hasakeh Sheikh El-Hadid Aghtrin Tall Refaat Al-HaPsakeh 1.5 m Afrin A'rima Sarin 3.87 m Jandairis Mare' Abu Qalqal Ein Issa Suluk Al Bab Nabul Hole From within Syria From neighbouring Daret AzzaHaritan Tadaf a Aleppo Harim Dana Rasm Haram El-Imam e Qourqeena JebelP Saman countries Eastern Kwaires Areesheh S Salqin Atareb Ar-Raqqa Dayr Hafir Jurneyyeh n Maaret Tamsrin As Safira Karama Shadadah a ArmaIndaz leTebftnaz Maskana Number of Food Basket Beneficiaries Darkosh ZarbahHadher Banan P e IdlePbBennsh n Kiseb Ar-Raqqa Jisr-Ash-Shugur Saraqab Hajeb by Sub District a Ariha Al-Thawrah Kisreh r Qastal MaafRabee'aBadama Markada Abul ThohurTall Ed-daman Maadan r Kansaba Ehsem e Ein El-Bayda Ziyara Ma'arrat An Nu'man Al-Khafsa < 10,000 t Khanaser Mansura Sabka i Al HafaSalanfa Sanjar Lattakia -

Examples of Iraq and Syria

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2017 The Unraveling of the Nation-State in the Middle East: Examples of Iraq and Syria Zachary Kielp Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kielp, Zachary, "The Unraveling of the Nation-State in the Middle East: Examples of Iraq and Syria" (2017). MSU Graduate Theses. 3225. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3225 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNRAVELING OF THE NATION-STATE IN THE MIDDLE EAST: EXAMPLES OF IRAQ AND SYRIA A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Defense and Strategic Studies By Zachary Kielp December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Zachary Kielp ii THE UNRAVELING OF THE NATION-STATE IN THE MIDDLE EAST: EXAMPLES OF IRAQ AND SYRIA Defense and Strategic Studies Missouri State University, December 2017 Master of Science Zachary Kielp ABSTRACT After the carnage of World War One and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire a new form of political organization was brought to the Middle East, the Nation-State. -

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Movements December 2020 IDP (Wos) Task Force

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Movements December 2020 IDP (WoS) Task Force December 2020 updates Governorate summary 19K In December 2020, the humanitarian community tracked some 43,000 IDP Aleppo 17K movements across Syria, similar to numbers tracked in November. As in 25K preceding months, most IDP movements were concentrated in northwest 21K Idleb 13K Syria, with 92 percent occurring within and between Aleppo and Idleb 15K governorates. 800 Ar-Raqqa 800 At the sub-district level, Dana in Idleb governorate and Ghandorah, Bulbul and 800 Sharan in Aleppo governorate each received around 2,800 IDP movements in 443 Lattakia 380 December. Afrin sub-district in Aleppo governorate received around 2,700 830 movements while Maaret Tamsrin sub-district in Idleb governorate and Raju 320 Tartous 230 71% sub-district in Aleppo governorate each received some 2,500 IDP movements. 611 of IDP arrivals At the community level, Tal Aghbar - Tal Elagher community in Aleppo 438 occurred within Hama 43 governorate received the largest number of displaced people, with around 350 governorate 2,000 movements in December, followed by some 1,000 IDP movements 245 received by Afrin community in Aleppo governorate. Around 800 IDP Homs 105 122 movements were received by Sheikh Bahr community in Aleppo governorate 0 Deir-ez-Zor and Ar-Raqqa city in Ar-Raqqa governorate, and Lattakia city in Lattakia 0 IDPs departure from governorate 290 n governorate, Koknaya community in Idleb governorate and Azaz community (includes displacement from locations within 248 governorate and to outside) in Aleppo governorate each received some 600 IDP movements this month. -

Palmyra (Tadmor) اريملاب

بالميرا (Palmyra (Tadmor Homs Governorate 113 Ancient city of Palmyra/Photo: Creative Commonts, Wikipedia Satellite-based Damage Asessment to Historial Sites in Syria SOUTHWEST ACROPOLIS VALLEY OF TOMBS SMOOTHING OR EXCAVATING CITY ROMAN WALL OF SOILS IN AREA AS OF AIN EFQA BREACHED AS OF 14 NOV 2013 SPRING 14 NOV 2013 NORTHWEST NECROPOLIS EXCAVATED AS OF 1 SEPTEMBER 2012 MULTIPLE BERMS CAMP OF DIOLETIAN CONSTRUCTED ALL THROUGHOUT THE NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN NECROPOLIS COLONNADED NEW ROAD OF STREET APPROX.2.4 KM LONG CONSTRUCTED AS OF 14 NOV 2013 CITY WALL (SOUTHERN SECTION) TEMPLE OF NORTHERN BAAL-SHAMIN NECROPOLIS COLLAPSED COLUMN AS OF 13 NOV 2013 MONUMENTAL HOTEL ARCH ZENOBLA TEMPLE OF BEL CITY WALL (NORTHERN SECTION) RIGHT TO SECTION OF COLUMN ROW SOUTHEAST MISSING AS OF ACROPOLIS 14 NOV 2013 RIGHT HAND COLUMN OF COLUMN ROW MISSING AS OF 8 MARCH 2014 FIGURE 71. Overview of Palmyra and locations where damage has ocurred and is visible. Site Description This area covers the World Heritage Property of Palmyra (inscribed in 1980 and added to the UNESCO List of World Heritage in Danger in 2013. Built on an oasis in the desert, Palmyra contains the monumental ruins of a great city that was one of the most important cultural centres of the ancient world. From the first to the second century, the art and ar- chitecture of Palmyra, standing at the crossroads of several civilizations, PALMYRA married Graeco-Roman techniques with local traditions and Persian in- fluences: “The splendour of the ruins of Palmyra, rising out of the Syrian de- sert northeast of Damascus is testament to the unique aesthetic achievement of a wealthy caravan oasis intermittently under the rule of Rome[…] The [streets and buildings] form an outstanding illustration of architecture and urban layout at the peak of Rome’s expansion in and engagement with the East. -

The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras policy focus 132 | december 2013 the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessar- ily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. MAPS Fig. 1 based on map designed by W.D. Langeraar of Michael Moran & Associates that incorporates data from National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, UNEP- WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, and iPC. Figs. 2, 3, and 4: detail from The Tourist Atlas of Syria, Syria Ministry of Tourism, Directorate of Tourist Relations, Damascus. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2013 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Digitally rendered montage incorporating an interior photo of the tomb of Hafez al-Assad and a partial view of the wheel tapestry found in the Sheikh Daher Shrine—a 500-year-old Alawite place of worship situated in an ancient grove of wild oak; both are situated in al-Qurdaha, Syria. Photographs by Andrew Tabler/TWI; design and montage by 1000colors. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

Political Economy Report English F

P a g e | 1 P a g e | 2 P a g e | 3 THE POLITICAL ECONOMY And ITS SOCIAL RAMIFICATIONS IN THREE SYRIAN CITIES: TARTOUS, Qamishli and Azaz Economic developments and humanitarian aid throughout the years of the conflict, and their effect on the value chains of different products and their interrelation with economic, political and administrative factors. January 2021 P a g e | 4 KEY MESSAGES • The three studied cities are located in different areas of control: Tartous is under the existing Syrian authority, Azaz is within the “Euphrates Shield” areas controlled by Turkey and the armed “opposition” factions loyal to it, and most of Qamishli is under the authority of the “Syrian Democratic Forces” and the “Self-Administration” emanating from it. Each of these regions has its own characteristics in terms of the "political war economy". • After ten years of conflict, the political economy in Syria today differs significantly from its pre-conflict conditions due to specific mechanisms that resulted from the war, the actual division of the country, and unilateral measures (sanctions). • An economic and financial crisis had hit all regions of Syria in 2020, in line with the Lebanese crisis. This led to a significant collapse in the exchange rate of the Syrian pound and a significant increase in inflation. This crisis destabilized the networks of production and marketing of goods and services, within each area of control and between these areas, and then the crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated this deterioration. • This crisis affected the living conditions of the population. The monthly minimum survival expenditure basket (SMEB) defined by aid agencies for an individual amounted to 45 working days of salaries for an unskilled worker in Azaz, 37 days in Tartous and 22 days in Qamishli. -

Torture Methods the Syrian Regime Continues to Practice in Its Detention Centers and Military Hospitals

Documentation of 72 Torture Methods the Syrian Regime Continues to Practice in Its Detention Centers and Military Hospitals Identifying 801 Individuals Who Appeared in Caesar Photographs, the US Congress Must Pass the Caesar Act to Provide Accountability Monday, October 21, 2019 1 snhr [email protected] www.sn4hr.org R190912 The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), founded in June 2011, is a non-governmental, independent group that is considered a primary source for the OHCHR on all death toll-related analyses in Syria. Contents I. Introduction and methodology of the report II. The Syrian Network for Human Rights’ cooperation with the UN Rapporteur on deaths due to Torture III. The toll of victims who died due to torture according to the SNHR’s database IV. The most notable methods of torture in the Syrian regime’s detention centers Physical torture Health neglect, conditions of detention and deprivation Sexual violence Psychological torture and humiliation of human dignity Forced labor Torture in military hospitals Separation V. New identification of 29 individuals who appeared in Caesar photographs leaked from military hospitals VI. Examples of individuals shown in Caesar photographs who we were able to identify VII. Various testimonies of torture incidents by survivors of the Syrian regime’s detention centers VIII. The most notable individuals responsible for torture in the Syrian regime’s detention centers according to the SNHR’s database IX. Conclusions and recommendations 1 snhr [email protected] www.sn4hr.org I. Introduction and methodology of the report: Hundreds of thousands of Syrians have been subjected to abduction (detention) by Syrian Regime forces; according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights’ (SNHR) database, at least 130,000 individuals are still detained or forcibly disappeared by the Syrian regime since the start of the popular uprising for democracy in Syria in March 2011. -

A New Model for Analyzing Sociolinguistic Variation Within the Framework of Optimality Theory (OT) and the Gradual Learning Algorithm (GLA)

NEW MODEL FOR ANALYZING SOCIOLINGUISTIC VARIATION: THE INTERACTION OF SOCIAL AND LINGUISTIC CONSTRAINTS By RANIA HABIB A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 Rania Habib 2 To my parents: Ibrahim and Amira To my sister: Suzi To my brothers: Husam and Faraj I love you …. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study owes a great deal to my adviser, Professor Fiona McLaughlin. Although I did not take a course with her, I had a very nice experience working with her as a Research Assistant in “The Project on the Languages of Urban Africa.” I admired her eloquence and personality from the time I met her and when she attended one of our Research Methods class as a visiting professor. In that class, Dr. McLaughlin shared her experience with us about collecting data in Senegal in Africa as part of an introduction to Field Methods. She has been very kind and listened closely whenever I felt hesitant towards making a decision. She has been supportive in my job search and promoting my research and me among colleagues. This study also owes a great deal to Professor Caroline Wiltshire who has helped me with the Gradual Learning Algorithm (GLA). My interest in GLA started when I was taking Issues in Phonology with her. Then, I wrote a paper for that class, using the idea of the GLA. This idea extended to my study in greater depth. She has been caring and supportive from the time I came to UF as a Fulbright student. -

Aleppo Governorate

Suruc ﺳورودج Oguzeli d أوﻏوﻠﯾزﯾﮫ d Şanlıurfa أوﻓﺔر DOWNLOAD MAP ZobarZorabi - C1948 اﻟﺠﻤﻬﻮرﻳﺔ اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ اﻟﺴــﻮرﻳﺔ SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC Estiqama زوﺑﺎر _زوراﺑﻲ - BabnBoban d C1975 C1966 d AinAlArab اﻻﻘﻣﺳﺎﺔﺗﻛ_ورﺑﺎ d C1946 ﺑﺎﺑﺎن _ﺑوﺑﺎن OrubaKor - Ali d ﻌﻟﻋرﯾ انب -Musabeyli Susan Sus C1956 MorshedMorshed Binar d d Reference Map C1980 Minasﻣوﺳﻠﺎﯾﺑﯾﮫ BijanTramk ﻋروﺑﺔﻛﻠ_ﻲو ﻋر ALEPPO GOVERNORATE d C1987 d C6340 Sharan ﺻو ص _ﺻوﺻﺎن C1961 ﻣرﻣ ﺷردﻧ ﺷﺑﺎدﯾر d - C1940 NafKarabnafKarab ﻧﺎﻣﯾس UpperQurran d Scan it! Navigate! d ﺑﯾﺟﺎن _ﺗﻣرك BigDuwara Jraqli - Qola d C1988 ﺷران with QR reader App with Avenza PDF C2021 d C1998 d Gh arib ﻧﺎﻛ رف بﻛ_ﻧرﺎﺑف C1990 AziziyehMom - anAzu Kalmad FirazdaqArsalan - Tash ﻗﻧﻲﻗﻓرﺎاو ن Maps App ﺧﺮﻳــﻄﺔ ﻣﺮﺟــﻌﻴﺔ d TalHajib d C6341 C1943 ﻗوﻻ ﻟداوﻛاﻟﺑﯾ راةرة _ﻠﻲﺟﺎﻗر Gaziantep d d d C1974 C1954 ﻣﺤــــﺎﻓـﻈـﺔ ﺣﻠﺐ ﻏرﯾ ب d C1949 d ﻣﻠدﻛ ﺗ لﺣﺎ ﺟ بd ﻔﻟرزادق_أرﺳﻼ طﺎن ش d ﻋزﯾزﯾﺔﻣ_ﻣوﺎ ﻋنزو Polateli Jebnet Shakriyeh- UpperJbeilehQorrat - Quri d KharabNas Karkamis C1995 d Mashko C1972 ﺑوﻠﻻﯾﺗﯾﮫ -QantarraQantaret Kikan ﻏﺎﻧﺗز ﺎﻋيب d s C1994 d Qarruf YadiHbabQawi - KorbinarNabaa - BigEin Elbat C1967ﺟlu/ﻠabرا aJrﺑس C1936 ﻧﻲﻗﻗﻓﻗﺎوو ﻠ_رﺟﺑﺔةرﯾي ﻧﺟﺔﺑ ﻛﺎﻛﻣرﺎﯾ س ﺧرﻧاﺎ بس d C1985 C1976 C1962 C1957 ﻟﺷاﻛﺎرﯾﺔﻣ_ﻛﺷو d d ﻧطﻘﻧرطﻟﻛةﻛﻗ ﯾﺎرا_ةن KherbetAtu d ﻛﺎ isﻛﻣ/رﺎﯾ amسKark ﻛ ﻟﻋﺑﯾﺑﯾ طانر KharanKort ﻧﻌﺑﺔﻟﻛ_اورﻧﺑﺎﯾر ﻟﺣاﺑﺎ ب ﯾﻗ_دو يي ﻗروف Jarablus Shankal ] C2001 d d d JilJilak d MeidanEkbis Kusan C2227 ShehamaBandar - C1968 C1482 d C2012 C1964 ﺧر ﺑﻋطﺔو C1488 C1490d d ﺧراﻛ وبرت d UpperDar Elbaz BigMazraet Sofi ﺟﻠراﺑس - HjeilehJrables ﺟﯾل _ﻠكﺟﯾ MaydanKork - Kitan -

Constructivism; Instrumentalism; Syria

Sectarianism or Geopolitics? Framing the 2011 Syrian Conflict by Tasmia Nower B.A & B.Sc., Quest University Canada, 2015 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School for International Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Tasmia Nower SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2017 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Tasmia Nower Degree: Master of Arts Title: Sectarianism or Geopolitics? Framing the 2011 Syrian Conflict Examining Committee: Chair: Gerardo Otero Professor Tamir Moustafa Senior Supervisor Professor Nicole Jackson Supervisor Associate Professor Shayna Plaut External Examiner Adjunct Professor School for International Studies Simon Fraser University Date Defended/Approved: August 1, 2017 ii Abstract The Syrian conflict began as an uprising against the Assad regime for political and economic reform. However, as violence escalated between the regime and opposition, the conflict drew in Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia, which backed both the regime and opposition with resources. The current conflict is described as sectarian because of the increasingly antagonistic relations between the Shiite/Alawite regime and the Sunni- dominated opposition. This thesis examines how sectarian identity is politicized by investigating the role of key states during the 2011 Syrian conflict. I argue that the Syrian conflict is not essentially sectarian in nature, but rather a multi-layered conflict driven by national and regional actors through the selective deployment of violence and rhetoric. Using frame analysis, I examine Iranian, Turkish, and Saudi Arabian state media coverage of the Syrian conflict to reveal the respective states’ political position and interest in Syria.