The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Distr.: General 18 March 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Oral Update of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic 1 I. Introduction 1. The harrowing violence in the Syrian Arab Republic has entered its fourth year, with no signs of abating. The lives of over one hundred thousand people have been extinguished. Thousands have been the victims of torture. The indiscriminate and disproportionate shelling and aerial bombardment of civilian-inhabited areas has intensified in the last six months, as has the use of suicide and car bombs. Civilians in besieged areas have been reduced to scavenging. In this conflict’s most recent low, people, including young children, have starved to death. 2. Save for the efforts of humanitarian agencies operating inside Syria and along its borders, the international community has done little but bear witness to the plight of those caught in the maelstrom. Syrians feel abandoned and hopeless. The overwhelming imperative is for the parties, influential states and the international community to work to ensure the protection of civilians. In particular, as set out in Security Council resolution 2139, parties must lift the sieges and allow unimpeded and safe humanitarian access. 3. Compassion does not and should not suffice. A negotiated political solution, which the commission has consistently held to be the only solution to this conflict, must be pursued with renewed vigour both by the parties and by influential states. Among victims, the need for accountability is deeply-rooted in the desire for peace. -

Examples of Iraq and Syria

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2017 The Unraveling of the Nation-State in the Middle East: Examples of Iraq and Syria Zachary Kielp Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kielp, Zachary, "The Unraveling of the Nation-State in the Middle East: Examples of Iraq and Syria" (2017). MSU Graduate Theses. 3225. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3225 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNRAVELING OF THE NATION-STATE IN THE MIDDLE EAST: EXAMPLES OF IRAQ AND SYRIA A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Defense and Strategic Studies By Zachary Kielp December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Zachary Kielp ii THE UNRAVELING OF THE NATION-STATE IN THE MIDDLE EAST: EXAMPLES OF IRAQ AND SYRIA Defense and Strategic Studies Missouri State University, December 2017 Master of Science Zachary Kielp ABSTRACT After the carnage of World War One and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire a new form of political organization was brought to the Middle East, the Nation-State. -

Palmyra (Tadmor) اريملاب

بالميرا (Palmyra (Tadmor Homs Governorate 113 Ancient city of Palmyra/Photo: Creative Commonts, Wikipedia Satellite-based Damage Asessment to Historial Sites in Syria SOUTHWEST ACROPOLIS VALLEY OF TOMBS SMOOTHING OR EXCAVATING CITY ROMAN WALL OF SOILS IN AREA AS OF AIN EFQA BREACHED AS OF 14 NOV 2013 SPRING 14 NOV 2013 NORTHWEST NECROPOLIS EXCAVATED AS OF 1 SEPTEMBER 2012 MULTIPLE BERMS CAMP OF DIOLETIAN CONSTRUCTED ALL THROUGHOUT THE NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN NECROPOLIS COLONNADED NEW ROAD OF STREET APPROX.2.4 KM LONG CONSTRUCTED AS OF 14 NOV 2013 CITY WALL (SOUTHERN SECTION) TEMPLE OF NORTHERN BAAL-SHAMIN NECROPOLIS COLLAPSED COLUMN AS OF 13 NOV 2013 MONUMENTAL HOTEL ARCH ZENOBLA TEMPLE OF BEL CITY WALL (NORTHERN SECTION) RIGHT TO SECTION OF COLUMN ROW SOUTHEAST MISSING AS OF ACROPOLIS 14 NOV 2013 RIGHT HAND COLUMN OF COLUMN ROW MISSING AS OF 8 MARCH 2014 FIGURE 71. Overview of Palmyra and locations where damage has ocurred and is visible. Site Description This area covers the World Heritage Property of Palmyra (inscribed in 1980 and added to the UNESCO List of World Heritage in Danger in 2013. Built on an oasis in the desert, Palmyra contains the monumental ruins of a great city that was one of the most important cultural centres of the ancient world. From the first to the second century, the art and ar- chitecture of Palmyra, standing at the crossroads of several civilizations, PALMYRA married Graeco-Roman techniques with local traditions and Persian in- fluences: “The splendour of the ruins of Palmyra, rising out of the Syrian de- sert northeast of Damascus is testament to the unique aesthetic achievement of a wealthy caravan oasis intermittently under the rule of Rome[…] The [streets and buildings] form an outstanding illustration of architecture and urban layout at the peak of Rome’s expansion in and engagement with the East. -

Syrian Jihadists Signal Intent for Lebanon

Jennifer Cafarella Backgrounder March 5, 2015 SYRIAN JIHADISTS SIGNAL INTENT FOR LEBANON Both the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) and the al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra (JN) plan to conduct attacks in Lebanon in the near term. Widely presumed to be enemies, recent reports of an upcoming joint JN and ISIS offensive in Lebanon, when coupled with ongoing incidents of cooperation between these groups, indicate that the situation between these groups in Lebanon is as fluid and complicated as in Syria. Although they are direct competitors that have engaged in violent confrontation in other areas, JN and ISIS have co-existed in the Syrian-Lebanese border region since 2013, and their underground networks in southern and western Lebanon may overlap in ways that shape their local relationship. JN and ISIS are each likely to pursue future military operations in Lebanon that serve separate but complementary objectives. Since 2013 both groups have occasionally shown a willingness to cooperate in a limited fashion in order to capitalize on their similar objectives in Lebanon. This unusual relationship appears to be unique to Lebanon and the border region, and does not extend to other battlefronts. Despite recent clashes that likely strained this relationship in February 2015, contention between the groups in this area has not escalated beyond localized skirmishes. This suggests that both parties have a mutual interest in preserving their coexistence in this strategically significant area. In January 2015, JN initiated a new campaign of spectacular attacks against Lebanese supporters of the Syrian regime, while ISIS has increased its mobilization in the border region since airstrikes against ISIS in Syria began in September 2014. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

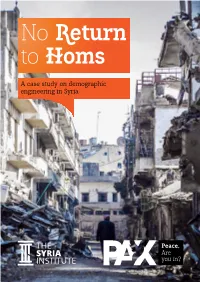

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

The Documentation of the Sectarian Massacre of Talkalakh City in Homs Governorate

SNHR is an independent, non-governmental, nonprofit, human rights organization that was founded in June 2011. SNHR is a Thursday 31 October 2013 certified source for the United Nation in all of its statistics. The Documentation of the Sectarian Massacre of Talkalakh City in Homs Governorate The documenting party: Syrian Network for Human Rights On Thursday 31 October 2013, about 11:00 pm, a group of “local committees” entered the house of an IDPs family in Al Zara village in Talkalakh city and slaugh- tered a woman and her two children with knives. The location on the map: Alaa Mameesh, the eldest son of the family, told SNHR about the slaughtering of his mother and two brothers at the hands of pro-regime forces Al Shabiha: “The family displaced from Al Zara village due to clashes between Free Army and the regime army which consists of 95% Alawites in that area. The family displaced to Talkalakh city which is controlled by the regime hoping the situation would be better there. When Al Shabiha knew that the building contains people from Al Zara village, they stormed the house and without any investigation they killed them all, my mother, my sister and my brother. My father, Fat-hi Mameesh is an officer in the regime army, he fought the Free Army in many battels. Al Shabiha haven’t asked my family about any information. They killed them only because they are IDPs from Al Zara village which is of a Sunni majority. We couldn’t identify anything about their corpses or whether they buried them or not because they banned anyone from Al Zara village to enter Talkalakh city” 1 www.sn4hr.org - [email protected] The victims’ names: The mother, Elham Jardi/ Homs/ Al Zara village/ (Um Alaa) Hanadi Fat-hi Mameesh, 19-year-old/ Homs/ Al Zara village Mohammad Fat-hi Mameesh, 17-year-old/ Al Zara village. -

Torture Methods the Syrian Regime Continues to Practice in Its Detention Centers and Military Hospitals

Documentation of 72 Torture Methods the Syrian Regime Continues to Practice in Its Detention Centers and Military Hospitals Identifying 801 Individuals Who Appeared in Caesar Photographs, the US Congress Must Pass the Caesar Act to Provide Accountability Monday, October 21, 2019 1 snhr [email protected] www.sn4hr.org R190912 The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), founded in June 2011, is a non-governmental, independent group that is considered a primary source for the OHCHR on all death toll-related analyses in Syria. Contents I. Introduction and methodology of the report II. The Syrian Network for Human Rights’ cooperation with the UN Rapporteur on deaths due to Torture III. The toll of victims who died due to torture according to the SNHR’s database IV. The most notable methods of torture in the Syrian regime’s detention centers Physical torture Health neglect, conditions of detention and deprivation Sexual violence Psychological torture and humiliation of human dignity Forced labor Torture in military hospitals Separation V. New identification of 29 individuals who appeared in Caesar photographs leaked from military hospitals VI. Examples of individuals shown in Caesar photographs who we were able to identify VII. Various testimonies of torture incidents by survivors of the Syrian regime’s detention centers VIII. The most notable individuals responsible for torture in the Syrian regime’s detention centers according to the SNHR’s database IX. Conclusions and recommendations 1 snhr [email protected] www.sn4hr.org I. Introduction and methodology of the report: Hundreds of thousands of Syrians have been subjected to abduction (detention) by Syrian Regime forces; according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights’ (SNHR) database, at least 130,000 individuals are still detained or forcibly disappeared by the Syrian regime since the start of the popular uprising for democracy in Syria in March 2011. -

Weekly Conflict Summary | 9 - 15 March 2020

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 9 - 15 MARCH 2020 WHOLE OF SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST | Conflict levels in the northwest remained low the week following a Russian/Turkish ceasefire agreement on 5 March. Protesters blocked a joint Russian/Turkish patrol on the M4 Highway. In Operation Euphrates Shield areas, attacks increased against Turkish-backed opposition armed groups. In the southeast corner of Aleppo Governorate, four alleged ISIS attacks occurred, the first in the area in over 2 years. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | Following Government of Syria (GoS) re- enforcements arriving to southern Syria, attacks against GoS personnel in Daraa Governorate decreased. For the second time in the month, an explosive device detonated in Damascus. In Homs Northern Countryside, gunmen opened fire against a GoS military officer. • NORTHEAST | In addition to shelling exchanges between SDF forces and Turkish-backed opposition groups around Operation Peace Spring area, ACLED reported increases in explosive attacks and looting activity. Attacks against Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) personnel and oil infrastructure along the Euphrates River Valley included a suicide attack, only the third in the preceding 12 months. Israeli airstrikes targeted the Abu Kamal area. Figure 1: Dominant actors’ area of control and influence in Syria as of 15 March 2020. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. Also, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 5 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 9 -15 March 2020 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 Conflict levels in northwest Syria decreased in the week following the implementation of a Turkish/Russian ceasefire agreement reached on 5 March. ACLED data recorded no GoS/Russian airstrikes in the northwest this week, and just 13 GoS shelling bombardments on eight locations.2 Hayyat Tahrir al Sham (HTS)-dominated opposition shelled two GoS locations; Qardaha town in Latakia Governorate and the Russian operated Hmeimim Airbase. -

Civilians in Hama

Syria: 13 Civilians Kidnapped by Security Services and Affiliate Militias in Hama www.stj-sy.org Syria: 13 Civilians Kidnapped by Security Services and Affiliate Militias in Hama Two young men were kidnapped by the National Defense Militia; the other 11, belonging to the same family, were abducted by a security service in Hama city. The abductees were all released in return for a ransom Page | 2 Syria: 13 Civilians Kidnapped by Security Services and Affiliate Militias in Hama www.stj-sy.org In November 2018 and February 2019, 13 civilians belonging to two different families were kidnapped by security services and the militias backing them in Hama province. The kidnapped persons were all released after a separate ransom was paid by each of the families. Following their release, a number of the survivors, 11 to be exact, chose to leave Hama to settle in Idlib province. The field researchers of Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ contacted several of the abduction survivors’ relatives, who reported that some of the abductees were subjected to severe torture and deprived of medications, which caused one of them an acute health deterioration. 1. The Kidnapping of Brothers Jihad and Abduljabar al- Saleh: The two young men, Jihad, 28-year-old, and Abduljabar, 25-year-old, are from the village of al-Tharwat, eastern rural Hama, from which they were displaced after the Syrian regular forces took over the area late in 2017, to settle in an IDP camp in Sarmada city. The brothers, then, decided to undergo legalization of status/sign a reconciliation agreement with the Syrian government to obtain passports and move in Saudi Arabia, where their family is based. -

Situation Report: WHO Syria, Week 19-20, 2019

WHO Syria: SITUATION REPORT Weeks 32 – 33 (2 – 15 August), 2019 I. General Development, Political and Security Situation (22 June - 4 July), 2019 The security situation in the country remains volatile and unstable. The main hot spots remain Daraa, Al- Hassakah, Deir Ezzor, Latakia, Hama, Aleppo and Idlib governorates. The security situation in Idlib and North rural Hama witnessed a notable escalation in the military activities between SAA and NSAGs, with SAA advancement in the area. Syrian government forces, supported by fighters from allied popular defense groups, have taken control of a number of villages in the southern countryside of the northwestern province of Idlib, reaching the outskirts of a major stronghold of foreign-sponsored Takfiri militants there The Southern area, particularly in Daraa Governorate, experienced multiple attacks targeting SAA soldiers . The security situation in the Central area remains tense and affected by the ongoing armed conflict in North rural Hama. The exchange of shelling between SAA and NSAGs witnessed a notable increase resulting in a high number of casualties among civilians. The threat of ERWs, UXOs and Landmines is still of concern in the central area. Two children were killed, and three others were seriously injured as a result of a landmine explosion in Hawsh Haju town of North rural Homs. The general situation in the coastal area is likely to remain calm. However, SAA military operations are expected to continue in North rural Latakia and asymmetric attacks in the form of IEDs, PBIEDs, and VBIEDs cannot be ruled out. II. Key Health Issues Response to Al Hol camp: The Security situation is still considered as unstable inside the camp due to the stress caused by the deplorable and unbearable living conditions the inhabitants of the camp have been experiencing . -

Hama Governorate, April 2018 OVERALL FINDINGS1

Hama Governorate, April 2018 Humanitarian Situation Overview in Syria (HSOS) OVERALL FINDINGS1 Coverage Hama governorate, located on the banks of the Orontes River, is positioned to the south of Idleb governorate and the north of Homs governorate. Offensives against the group known as the so-called Ziyara Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) throughout mid-2017 and into early 2018 have resulted in ALEPPO large-scale displacement, both within and out of the governorate to neighbouring Idleb. In April, conflict in Northern Hama governorate between opposition groups, ISIL, and government forces intensified. As a IDLEB result of prolonged conflict,33 of the 82 assessed communities estimated that less than 50% of pre-conflict Shat- populations remained. Additionally, Key Informants (KIs) in 24 of the assessed communities reported that ha further pre-conflict populations left their communities in April, primarily due to an escalation in conflict. Madiq Castle However, Mahruseh and Ankawi communities both experienced spontaneous IDP returns, approximately Hamra 208 in total2. Additionally, Mahruseh community also experienced approximately 67 spontaneous refugee returnees from Jordan, Turkey, and Lebanon in April. Please see the IDP Situation Monitoring Initiative As-SuqaylabiyahKarnaz Kafr Zeita (ISMI) April 2018 monthly report for further analysis. Suran Tell Salhib In 6 of the assessed communities, all in Hama and As-Suqaylabiyah districts, KIs estimated that between Muhradah 51-100% of the buildings in their communities were damaged. Additionally, seven communities reported that there was no electricity source available. In terms of water, 30 of the assessed communities reported Jeb Ramleh having an insufficient amount of water to meet household needs.