The Beginning of a New University Presidency Is Usually Associated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conference Attendees

CONFERENCE ATTENDEES Michelle Ackerman, CRM Product Manager, Brainworks, Sayville, NY Mark Adams, CEO, Adams Publishing Group, Coon Rapids, MN Mark Adams, Audience Acquisition/Retention Manager, The Post and Courier, Charleston, SC Mindy Aguon, CEO, The Guam Daily Post, Tamuning, GU Mickie Anderson, Local News Editor, The Gainesville Sun, Gainesville, FL Sara April, Vice President, Dirks, Van Essen, Murray & April, Santa Fe, NM Lloyd Armbrust, Chief Executive Officer, OwnLocal, Austin, TX Barry Arthur, Asst. Managing Editor Photo/Electronic Media, Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Little Rock, AR Gordon Atkinson, Sr. Director, Marketing, Newspapers.com, Lehi, UT Donna Barrett, President/CEO, CNHI, Montgomery, AL Dana Bascom, Senior Sales Executive, Newzware ICANON, Hatfield, PA Mike Beatty, President, Florida, Adams Publishing Group, Venice, FL Ben Beaver, Account Representative, Second Street, St. Louis, MO Bob Behringer, President, Presteligence, North Canton, OH Julie Bergman, Vice President, Newspaper Group, Grimes, McGovern & Associates, East Grand Forks, MN Eddie Blakeley, COO, Journal Publishing, Tupelo, MS Gary Blakeley, CEO, PAGE Cooperative, King of Prussia, PA Deb Blanchard, Marketing, Our Hometown, Inc., Clifton Springs, NY Mike Blinder, Publisher, Editor & Publisher, Lutz, FL Robin Block-Taylor, EVP, Client Services, NTVB MEDIA, Troy, MI Cory Bollinger (Elizabeth), The Villages Media, Bloomington, IN Devlyn Brooks, President, Modulist, Fargo, ND Eileen Brown, Vice President/Director of Strategic Marketing and Innovation, Daily Herald, Arlington Heights, IL PJ Browning, President/Publisher, The Post and Courier, Charleston, SC Wright Bryan, Partner Manager, LaterPay, New York, NY John Bussian, Attorney, Bussian Law Firm, Raleigh, NC Scott Campbell, Publisher, The Columbian Publishing Company, Vancouver, WA Brent Carter, Senior Director, Newspapers.com, Lehi, UT Lloyd Case (Ellen), Fargo, ND Scott Champion, CEO, Champion Media, Mooresville, NC Jim Clarke, Director - West, The Associated Press, Denver, CO Matt Coen, President, Second Street, St. -

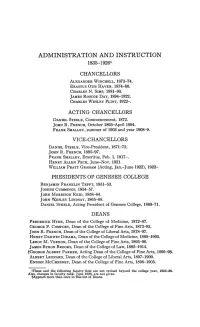

Administration and Instruction 1835-19261

ADMINISTRATION AND INSTRUCTION 1835-19261 CHANCELLORS ALEXANDER WINCHELL, 1873-74. ERASTUS OTIS H~VEN, 1874-80. CHARLES N. SIMS, 1881-93. ]AMES RoscoE DAY, 1894-1922. CHARLES WESLEY FLINT, 1922-. ACTING CHANCELLORS DANIEL STEELE, Commencement, 1872. ]OHN R. FRENCH, October 1893-April1894. FRANK SMALLEY, summer of 1903 and year 1908-9. VICE-CHANCELLORS D~NIEL STEELE, Vice-President, 1871-72. ]OHN R. FRENCH, 1895-97. FRANK SMALLEY, Emeritus, Feb. 1, 1917-. HENRY ALLEN PECK, June-Nov. 1921. WILLIAM PR~TT GRAHAM (Acting, Jan.-June 1922), 1922- :PRESIDENTS OF GENESEE COLLEGE BENJAMIN FRANKLIN TEFFT, 1851-53. JosEPH CuMMINGs, 1854-57. JOHN MoRRISON REID, 1858-64. ]OHN WESLEY LINDSAY, 1865-68. DANIEL STEELE, Acting President of Genesee College, 1869-71. DEANS FREDERICK HYDE, Dean of the College of Medicine, 1872-87. GEORGE F. CoMFORT, Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1873-93. JOHN R. FRENCH, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, 1878-97. HE~RY DARWIN DIDAMA, Dean of the College of Medicine, 1888-1905. LEROY M. VERNON, Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1893-96. ]AMES BYRON BROOKS, Dean of the College of Law, 1895-1914. tGEORGE ALBERT PARKER, Acting Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1896-98. ALBERT LEONARD, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, 1897-1900. ENSIGN McCHESNEY, Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1898-1905. IThese and the following faculty lists are not revised beyond the college year, 1925-26. Also, changes in faculty rank, June 1926, are not given. tAppears more than once in this list of Deans. ADMINISTRATION AND INSTRUCTION-DEANS Io69 FRANK SMALLEY, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts (Acting, Sept. -

The University of Michigan

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Michigan Legal Studies Series Law School History and Publications 1969 The niU versity of Michigan: Its Legal Profile William B. Cudlip Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/michigan_legal_studies Part of the Education Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Cudlip, William B. The nivU ersity of Michigan: Its Legal Profile. Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan, 1969. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School History and Publications at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Legal Studies Series by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN: ITS LEGAL PROFILE THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN: ITS LEGAL PROFILE by William B. Cudlip, J.D. Published under the auspices of The University of Michigan Law School (which, however, assumes no responsibility for the views expressed) with the aid of funds derived from a gift to The University of Michigan by the Barbour-Woodward Fund. Copyright© by The University of Michigan, 1969 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I suppose that lawyers are always curious about the legal history of any institution with which they are affiliated. As the University of Michigan approached its One Hundred Fiftieth year, my deep interest was heightened as I wondered about the legal structure and involvements of this durable edifice over that long period of time. This compendium is the result and I acknowledge the help that I have had. -

The University of Michigan Degrees Conferred by President and Level 1845-2008

The University of Michigan Degrees Conferred by President and Level 1845-2008 Degree Level Graduate Intermediate Graduate Cumulative President Total Bachelor Master Professional Doctor Professional Total GEORGE P. WILLIAMS 36 34 2 - - - 36 President of the Faculty 1845 & 1849 ANDREW TEN BROOK 34 29 5 - - - 70 President of the Faculty 1846 & 1850 DANIEL D. WHEDON 30 20 4 - - 6 100 President of the Faculty 1847 & 1851 J. HOLMES AGNEW 58 25 6 - - 27 158 President of the Faculty 1848 & 1852 HENRY P. TAPPAN 1011 355 143 12 - 501 1169 President of the University Aug. 12, 1852 - June, 1863 ERASTUS OTIS HAVEN 1543 219 124 56 - 1144 2712 President of the University June, 1863 - June, 1869 HENRY S. FRIEZE 1280 346 68 44 2 820 3992 Acting President Aug. 18, 1869 - Aug. 1, 1871 Also June, 1880 - Feb. 1882 & 1887 JAMES B. ANGELL 21040 8041 1056 155 139 11649 25032 President of the University Aug. 1, 1871 - Oct., 1909 HARRY BURNS HUTCHINS 13426 8444 1165 24 174 3619 38458 Acting President 1897-98 & 1909-10 President of the University June, 1910 - July, 1920 MARION LEROY BURTON 8127 5861 919 3 103 1241 46585 President of the Unliversity July, 1920 - Feb.. 1925 ALFRED HENRY LLOYD 1649 1124 183 1 33 308 48234 Acting President Feb. 27, 1925 - Sep. 1, 1925 CLARENCE COOK LITTLE 9338 6090 1568 10 246 1424 57572 President of the University Sept. 10, 1925 - Sept. 1, 1929 ALEXANDER GRANT RUTHVEN 76125 42459 22405 62 2395 8804 133697 President of the University Oct. 1, 1929 - Sep. 1, 1951 Office of the Registrar Report 502 Page 1 of 2 The University of Michigan Degrees Conferred by President and Level 1845-2008 Degree Level Graduate Intermediate Graduate Cumulative President Total Bachelor Master Professional Doctor Professional Total HARLAN H. -

United Methodist Bishops Page 17 Historical Statement Page 25 Methodism in Northern Europe & Eurasia Page 37

THE NORTHERN EUROPE & EURASIA BOOK of DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 2009 Copyright © 2009 The United Methodist Church in Northern Europe & Eurasia. All rights reserved. United Methodist churches and other official United Methodist bodies may reproduce up to 1,000 words from this publication, provided the following notice appears with the excerpted material: “From The Northern Europe & Eurasia Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church—2009. Copyright © 2009 by The United Method- ist Church in Northern Europe & Eurasia. Used by permission.” Requests for quotations that exceed 1,000 words should be addressed to the Bishop’s Office, Copenhagen. Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. Name of the original edition: “The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church 2008”. Copyright © 2008 by The United Methodist Publishing House Adapted by the 2009 Northern Europe & Eurasia Central Conference in Strandby, Denmark. An asterisc (*) indicates an adaption in the paragraph or subparagraph made by the central conference. ISBN 82-8100-005-8 2 PREFACE TO THE NORTHERN EUROPE & EURASIA EDITION There is an ongoing conversation in our church internationally about the bound- aries for the adaptations of the Book of Discipline, which a central conference can make (See ¶ 543.7), and what principles it has to follow when editing the Ameri- can text (See ¶ 543.16). The Northern Europe and Eurasia Central Conference 2009 adopted the following principles. The examples show how they have been implemented in this edition. -

Ssi»,!Ss??Ijts^Sriaig

THURSDAY, AUGUST '4, 1881—TEN PAGES. 2 THE CHICAGO TRIBUNE: thorlty, will forthwith proceed too.trculo thorn. loan Daw nro In use on this of |kTT" selling for.*' Tho call traveling In English ships. Hut mr Ideawns OBITUARY. side wr’ll see whom ho Is Umt these things wen* to bo put Into English CIMMINAL NEWS. Tho Cjunpaw* nro qunrim'd In tho J.ourMlomm. Just tlm same ns lots of Canadian bo*. clerk asked, ••What'** the name»’ Hatch re- They have two drills dally, nn<t tho hoys nro In NEW YORK. voice, war vessels like I ho Dntcrel." tho, In tlio Htatos. Tho foot of (ho sponded in stentorian good spirits. Tho oltl/i'iw of IVrryvlllo and matter is a® ur.x. THOMAS niANcis nomiKi:. oitiiiity tho affairs. and nro Americans have discovered that ll os “i:« Ft* hatch.” deplore condition of Salem, is in favor; o* one Uio of iho skirmishing fund, Sad Talc of a Promising Sunday' willing to evemhuur litttioirpower;ln leDoro Death at Ore., After a balance tholr tlmfi uum RS (hi Thl*enur'd a ißUecommution and surprise. A" of trustees peaco ihi ummjntsto." I[.K<;II combined to soil until said: "I don’t know much about Crowe. Ho nml hrliur tho violators to punishment. Bishop llenorter-"Tho Inspector tim ciill tied Painful Illness, of . tho Volume of ,; doesn't amount tomueh. Winn Is tho nso of Im- in Penn- that Tho Inoroaso in h<> i!nl<l £ AiMd hushelsof Hie total School Scholar specters sunt from tbo states had aViutillv to mortalizing midi an idiot? Our cause has suf- Unltctl siiTl iran-meilons <>r iho cull, which iniiouiitcil n pity to ImvO sylvania. -

Moving Beyond the Apple Orchard: the Institutional Analysis of the Construction of Washtenaw Community College Julie M

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations Graduate Capstone Projects 2017 Moving beyond the apple orchard: The institutional analysis of the construction of Washtenaw Community College Julie M. Kissel Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/theses Part of the Counseling Commons, and the Leadership Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kissel, Julie M., "Moving beyond the apple orchard: The institutional analysis of the construction of Washtenaw Community College" (2017). Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations. 834. http://commons.emich.edu/theses/834 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Graduate Capstone Projects at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: MOVING BEYOND THE APPLE ORCHARD Moving Beyond the Apple Orchard: The Institutional Analysis of the Construction of Washtenaw Community College by Julie M. Kissel Dissertation Eastern Michigan University Submitted to the Department of Leadership and Counseling Eastern Michigan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY Educational Leadership Dissertation Committee: Ronald Flowers Ed.D., Chair James Barott, Ph.D. David Anderson, Ed.D. Robert Orrange, Ph.D. July 6, 2017 Ypsilanti, Michigan Copyright 2017 by Kissel, Julie M. All rights reserved MOVING BEYOND THE APPLE ORCHARD i MOVING BEYOND THE APPLE ORCHARD ii Dedication My strength—Tim, Justin, Garrett, and Jillian. -

A History of the Conferences of Deans of Women, 1903-1922

A HISTORY OF THE CONFERENCES OF DEANS OF WOMEN, 1903-1922 Janice Joyce Gerda A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2004 Committee: Michael D. Coomes, Advisor Jack Santino Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen M. Broido Michael Dannells C. Carney Strange ii „ 2004 Janice Joyce Gerda All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Michael D. Coomes, Advisor As women entered higher education, positions were created to address their specific needs. In the 1890s, the position of dean of women proliferated, and in 1903 groups began to meet regularly in professional associations they called conferences of deans of women. This study examines how and why early deans of women formed these professional groups, how those groups can be characterized, and who comprised the conferences. It also explores the degree of continuity between the conferences and a later organization, the National Association of Deans of Women (NADW). Using evidence from archival sources, the known meetings are listed and described chronologically. Seven different conferences are identified: those intended for deans of women (a) Of the Middle West, (b) In State Universities, (c) With the Religious Education Association, (d) In Private Institutions, (e) With the Association of Collegiate Alumnae, (f) With the Southern Association of College Women, and (g) With the National Education Association (also known as the NADW). Each of the conferences is analyzed using seven organizational variables: membership, organizational structure, public relations, fiscal policies, services and publications, ethical standards, and affiliations. Individual profiles of each of 130 attendees are provided, and as a group they can be described as professional women who were both administrators and scholars, highly-educated in a variety of disciplines, predominantly unmarried, and active in social and political causes of the era. -

Catalogue Io Se Ate University of Mich

C AT ALO GUE I O S E A T E UNIVERSITY OF MI H AN C G , O F T H O S E W H O H AV E R EC EKV ED I T S R EGULAR AN D HON OR AR Y DEGR EE S . AN N AR BO R P U B L I S H E D B Y T H E U N I V E R S I T Y . C O N T E N T S . of Arts Bachelors , of exce t n Bachelors Philosophy, p those amed under some e oth r title, . page of Bachelors Science, except those named under some other title, . page Civil Engineers, except those named under some other title, page 1 t Mining Engineers, except those named under some othe itle, page o ther title, page 42 4 . page 3 of Law, except those named under some other title, page 55 Ad eundem 6 Post Graduate and degrees, . page 7 page 69 AN EXPL AT I O N S . This mark (t)indicates those Wh o have served in the Union Presidents of universities and colleges, and the higher national ffi . and state o cers, are indicated by capitals Whol e n umb er of those Wh o have received degrees . Livin g Whole n umber of Al umni D eceased Living W h ole n umber of B achel ors of Arts D eceas ed h n um b er of B ach e or of Ph oso h e ce W ole l s il p y, x pt un der som o her head e t , W hol e n um be of Bachel ors S i en ce e ce t thos r of c , x p e som e other head W hole n m ber of C i il En in ee s e ce hose atalo ued un der som e u v g r , x pt t c g D eceased Living W hol e n um b er of M in in En ineers e ce th ose catal o ed n der s m g g , x pt gu u o e oth er h ead D eceased Living hol e n um b er of Ph arm ace ical C hem is s e ce hose ca alo ued nu W ut t , x pt t t g der som e oth er h ead ho e n um ber of D oc ors of M ed cin e e ce hose ca a o ued n der W l t i , x pt t t l g u som e other head D eceased som e other head Whol e n um b er of Pos t Graduate D egrees con ferred Wh ole n um ber of H on orary D egrees con ferred A A EM I E A C D C S N T E. -

D1a-Marilyn-Mason-Celebrates-60

DANCING MARILYN MASON CELEBRATES 60 YEARS “Marilyn Mason literally walked up and down the pedal board at the Kennedy Center organ. … As she worked her way through the impassioned pages she resembled some hieratic priestess performing a dance of grief on the keyboards. … Sowerby’s jubilant Pageant closed the evening, in a blaze of harmonies and pedal virtuosity.” The Evening Star and Daily News, Washington, D.C., June 19, 1973 his fall, Marilyn Mason, chair of the department of organ since 1960, University Organist since 1976, will mark sixty years on the faculty — a T first, according to official University records. To celebrate her remarkable achievements, the 47th Conference on Organ Music, held on campus annually since Mason originated them in 1960, was dedicated to her. And this was no retirement party, mind you. Mason’s not going anywhere. And what, after all, would we do without her? Consider sixty years. When Marilyn joined the faculty, Alexander Ruthven was University President — followed by Harlan Hatcher, Robben Fleming, Harold Shapiro, James Duderstadt, Lee Bollinger, and Mary Sue Coleman. Harry Truman was president. A new car was the princely sum of $800; a gallon of gaso- line cost 18¢. Minimum wage was 30¢ an hour and the average worker earned Fall 2007 3 “Palmer Christian told me that a ‘buzz bomb’ from Oklahoma had walked in that day,” recalled friend and fellow organist Mary McCall Stubbins. $1,900 … a year. The oldest baby In 1944, Palmer Christian wrote a boomers you know now were still in guarded yet enthusiastic letter to a diapers. -

The Making of University of Michigan History Accessed 2/23/2015

The Making of University of Michigan History Accessed 2/23/2015 Home Exhibits Reference University Records Michigan History Digital Curation Search Home > Exhibits > Myumich The Making of University of Michigan History: The People, Events, & Buildings that Shaped the University 1899/1900 C. H. Cooley, teaches 1st sociology course 1904/1905 West Engineering Hall opens 1905/1906 Emil Lorch heads new Architecture Dept. 1905/1906 Women's Athletic Assoc. formed 1909 Pres. James B. Angell retires 1909/1910 Alumni Hall dedicated 1910 Harry B. Hutchins, 6th UM President 1911/1912 "Club House" constructed at Ferry Field 1911/1912 Graduate School founded 1914 Hill Auditorium opens 1915 First women's dorms open http://bentley.umich.edu/exhibits/myumich/ 1 / 52 The Making of University of Michigan History Accessed 2/23/2015 1918 Old University Library closed 1918/1919 SATC constructing mess hall 1921 Marion Leroy Burton named president 1923/1924 William L. Clements Library opens 1926/1927 Dana, Moore named deans of new schools 1929 Women's League opens 1929/1930 Ruthven assumes UM presidency 1931/1932 McMath-Hulbert Observatory opens 1933/1934 Law Quad construction completed 1936 Mayfest brings Ormandy to Ann Arbor 1938/1939 West Quad dorms built as WPA project 1939 Arthur Miller, wins second Hopwood 1940/1941 War issue stirs campus 1942/1943 JAG School troops drill in Law Quad http://bentley.umich.edu/exhibits/myumich/ 2 / 52 The Making of University of Michigan History Accessed 2/23/2015 1943/1944 Ruth Buchanan writes to soldiers 1945/1946 Returning -

The Book of Discipline

THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH “The Book Editor, the Secretary of the General Conference, the Publisher of The United Methodist Church and the Committee on Correlation and Editorial Revision shall be charged with edit- ing the Book of Discipline. The editors, in the exercise of their judgment, shall have the authority to make changes in wording as may be necessary to harmonize legislation without changing its substance. The editors, in consultation with the Judicial Coun- cil, shall also have authority to delete provisions of the Book of Discipline that have been ruled unconstitutional by the Judicial Council.” — Plan of Organization and Rules of Order of the General Confer- ence, 2016 See Judicial Council Decision 96, which declares the Discipline to be a book of law. Errata can be found at Cokesbury.com, word search for Errata. L. Fitzgerald Reist Secretary of the General Conference Brian K. Milford President and Publisher Book Editor of The United Methodist Church Brian O. Sigmon Managing Editor The Committee on Correlation and Editorial Revision Naomi G. Bartle, Co-chair Robert Burkhart, Co-chair Maidstone Mulenga, Secretary Melissa Drake Paul Fleck Karen Ristine Dianne Wilkinson Brian Williams Alternates: Susan Hunn Beth Rambikur THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 2016 The United Methodist Publishing House Nashville, Tennessee Copyright © 2016 The United Methodist Publishing House. All rights reserved. United Methodist churches and other official United Methodist bodies may re- produce up to 1,000 words from this publication, provided the following notice appears with the excerpted material: “From The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church—2016.