The University of Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitution of Michigan of 1835

Constitution of Michigan of 1835 In convention, begun at the city of Detroit, on the second Monday of May, in the year one thousand eight hundred and thirty five: Preamble. We, the PEOPLE of the territory of Michigan, as established by the Act of Congress of the Eleventh day of January, in the year one thousand eight hundred and five, in conformity to the fifth article of the ordinance providing for the government of the territory of the United States, North West of the River Ohio, believing that the time has arrived when our present political condition ought to cease, and the right of self-government be asserted; and availing ourselves of that provision of the aforesaid ordinance of the congress of the United States of the thirteenth day of July, one thousand seven hundred and eighty-seven, and the acts of congress passed in accordance therewith, which entitle us to admission into the Union, upon a condition which has been fulfilled, do, by our delegates in convention assembled, mutually agree to form ourselves into a free and independent state, by the style and title of "The State of Michigan," and do ordain and establish the following constitution for the government of the same. ARTICLE I BILL OF RIGHTS Political power. First. All political power is inherent in the people. Right of the people. 2. Government is instituted for the protection, security, and benefit of the people; and they have the right at all times to alter or reform the same, and to abolish one form of government and establish another, whenever the public good requires it. -

ERRS PRICE DESCRIPTORS the Tmergence.Of the Junior College In

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 116.741 Ja 760 060 AUTHOR Cowley, W. H. TITLE The tmergence.of the Junior College in the EvolutiOn of American Education: A Memorandum for the Fund for / Advancement of Education. SPOTS AGENCY Ford Foundation, New York, N.Y. PUB DATE 10 Sep 55 NOTE 61p. ERRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$3.32 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Change Agents; *Colleges; *Educational History; *Junior Colleges; Post Secondary Education; Professional Education; *Secondary-Schools; *Universities ABSTRACT In an/effort to elucidate the forces behind the emergence of the Ametican junior college, this document reviews the evolution of the structure of American education from 1874 to 1921. The historical review begins with 1874 because the decision made that year in the Kdlamazoo Case confirmed the right of communities to high schools by taxation. It ends with 1921 because two pisurrtt tal events occurred in that year: first, the organization of the American Association of Junior Colleges, and second, the establishtent of the first unitari.two..year junior college, namely, ,Modesto Junior College in Modesto, California. It reviews the historical development of secondary schools, liberal arts colleges, professional schools, universities, and junior colleges in that time period. The author/concludes that the junior college of today is an historical accident. A bibliography is appended. (DC) , *******************************************************t************ * Documents acquired by 'ERIC include many'-informal unpublished * * materials not available,from other sources. ERIC makes every effort*. * to obtain the bestopyNc available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * *via the ERIC Document Reproduction Servi9e (EDRS). -

Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White</H1>

Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White Scanned by Charles Keller with OmniPage Professional OCR software Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White Volume II Scanned by Charles Keller with OmniPage Professional OCR software donated by Caere Corporation, 1-800-535-7226. Contact Mike Lough AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ANDREW DICKSON WHITE WITH PORTRAITS VOLUME I page 1 / 895 NEW YORK THE CENTURY CO. 1905 Copyright, 1904, 1905, by THE CENTURY CO. ---- Published March, 1905 THE DE VINNE PRESS TO MY OLD STUDENTS THIS RECORD OF MY LIFE IS INSCRIBED WITH MOST KINDLY RECOLLECTIONS AND BEST WISHES TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I--ENVIRONMENT AND EDUCATION CHAPTER I. BOYHOOD IN CENTRAL NEW YORK--1832-1850 The ``Military Tract'' of New York. A settlement on the headwaters of the Susquehanna. Arrival of my grandfathers and page 2 / 895 grandmothers. Growth of the new settlement. First recollections of it. General character of my environment. My father and mother. Cortland Academy. Its twofold effect upon me. First schooling. Methods in primary studies. Physical education. Removal to Syracuse. The Syracuse Academy. Joseph Allen and Professor Root; their influence; moral side of the education thus obtained. General education outside the school. Removal to a ``classical school''; a catastrophe. James W. Hoyt and his influence. My early love for classical studies. Discovery of Scott's novels. ``The Gallery of British Artists.'' Effect of sundry conventions, public meetings, and lectures. Am sent to Geneva College; treatment of faculty by students. A ``Second Adventist'' meeting; Howell and Clark; my first meeting with Judge Folger. Philosophy of student dissipation at that place and time. -

Conference Attendees

CONFERENCE ATTENDEES Michelle Ackerman, CRM Product Manager, Brainworks, Sayville, NY Mark Adams, CEO, Adams Publishing Group, Coon Rapids, MN Mark Adams, Audience Acquisition/Retention Manager, The Post and Courier, Charleston, SC Mindy Aguon, CEO, The Guam Daily Post, Tamuning, GU Mickie Anderson, Local News Editor, The Gainesville Sun, Gainesville, FL Sara April, Vice President, Dirks, Van Essen, Murray & April, Santa Fe, NM Lloyd Armbrust, Chief Executive Officer, OwnLocal, Austin, TX Barry Arthur, Asst. Managing Editor Photo/Electronic Media, Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Little Rock, AR Gordon Atkinson, Sr. Director, Marketing, Newspapers.com, Lehi, UT Donna Barrett, President/CEO, CNHI, Montgomery, AL Dana Bascom, Senior Sales Executive, Newzware ICANON, Hatfield, PA Mike Beatty, President, Florida, Adams Publishing Group, Venice, FL Ben Beaver, Account Representative, Second Street, St. Louis, MO Bob Behringer, President, Presteligence, North Canton, OH Julie Bergman, Vice President, Newspaper Group, Grimes, McGovern & Associates, East Grand Forks, MN Eddie Blakeley, COO, Journal Publishing, Tupelo, MS Gary Blakeley, CEO, PAGE Cooperative, King of Prussia, PA Deb Blanchard, Marketing, Our Hometown, Inc., Clifton Springs, NY Mike Blinder, Publisher, Editor & Publisher, Lutz, FL Robin Block-Taylor, EVP, Client Services, NTVB MEDIA, Troy, MI Cory Bollinger (Elizabeth), The Villages Media, Bloomington, IN Devlyn Brooks, President, Modulist, Fargo, ND Eileen Brown, Vice President/Director of Strategic Marketing and Innovation, Daily Herald, Arlington Heights, IL PJ Browning, President/Publisher, The Post and Courier, Charleston, SC Wright Bryan, Partner Manager, LaterPay, New York, NY John Bussian, Attorney, Bussian Law Firm, Raleigh, NC Scott Campbell, Publisher, The Columbian Publishing Company, Vancouver, WA Brent Carter, Senior Director, Newspapers.com, Lehi, UT Lloyd Case (Ellen), Fargo, ND Scott Champion, CEO, Champion Media, Mooresville, NC Jim Clarke, Director - West, The Associated Press, Denver, CO Matt Coen, President, Second Street, St. -

Amending and Revising State Constitutions J

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 35 | Issue 2 Article 2 1947 Amending and Revising State Constitutions J. E. Reeves University of Kentucky Kenneth E. Vanlandingham University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Reeves, J. E. and Vanlandingham, Kenneth E. (1947) "Amending and Revising State Constitutions," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 35 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol35/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMENDING AND REVISING STATE CONSTITUTIONS J. E. REEVES* and K-ENNETii E. VANLANDINGHAMt Considerable interest in state constitutional revision has been demonstrated recently. Missouri and Georgia adopted re- vised constitutions in 1945 and New Jersey voted down a pro- posed revision at the general election in 1944. The question of calling a constitutional convention was acted upon unfavorably by the Illinois legislature in May, 1945, and the Kentucky legis- lature, at its 1944 and 1946 sessions, passed a resolution submit- ting" the question of calling a constitutional convention to the people of the state who will vote upon it at the general election in 1947. The reason for this interest in revision is not difficult to detect. -

Front Matter

Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page vii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Contents List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi INTRODUCTION The Cultural Cornerstone of the Ivory Tower 1 CHAPTER ONE Physical Culture, Discipline, and Higher Education in 1800s America 14 CHAPTER TWO Progressive Era Universities and Football Reform 40 CHAPTER THREE Psychologists: Body, Mind, and the Creation of Discipline 71 CHAPTER FOUR Social Scientists: Making Sport Safe for a Rational Public 93 CHAPTER FIVE Coaches: In the Disciplinary Arena 115 CHAPTER SIX Stadiums: Between Campus and Culture 139 CHAPTER SEVEN Academic Backlash in the Post–World War I Era 171 EPILOGUE A Circus or a Sideshow? 200 Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page viii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. viii Contents Notes 207 Bibliography 269 Index 305 Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page ix © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Illustrations 1. Opening ceremony, Leland Stanford Junior University, October 1891 2 2. Walter Camp, captain of the Yale football team, circa 1880 35 3. Grant Field at Georgia Tech, 1920 41 4. Stagg Field at the University of Chicago 43 5. William Rainey Harper built the University of Chicago’s academic reputation and also initiated big-time athletics at the institution 55 6. Army-Navy game at the Polo Grounds in New York, 1916 68 7. G. T. W. Patrick in 1878, before earning his doctorate in philosophy under G. -

The Judicial Branch

Chapter V THE JUDICIAL BRANCH The Judicial Branch . 341 The Supreme Court . 342 The Court of Appeals . 353 Michigan Trial Courts . 365 Judicial Branch Agencies . 381 2013– 2014 ORGANIZATION OF THE JUDICIAL BRANCH Supreme Court 7 Justices State Court Administrative Office Court of Appeals (4 Districts) 28 Judges Circuit Court Court of Claims (57 Circuits) Hears claims against the 218 Judges State. This is a function of General Jurisdiction the 30th Judicial Circuit Court, includes Court (Ingham County). Family Division Probate District Court Municipal Court (78 Courts) (104 Districts) (4 Courts) 103 Judges 248 Judges 4 Judges Certain types of cases may be appealed directly to the Court of Appeals. The Constitution of the State of Michigan of 1963 provides that “The judicial power of the state is vested exclusively in one court of justice which shall be divided into one supreme court, one court of appeals, one trial court of general jurisdiction known as the circuit court, one probate court, and courts of limited jurisdiction that the legislature may establish by a two-thirds vote of the members elected to and serving in each house.” Michigan Manual 2013 -2014 Chapter V – THE JUDICIAL BRANCH • 341 THE SUPREME COURT JUSTICES OF THE MICHIGAN SUPREME COURT Term expires ROBERT P. YOUNG, JR., Chief Justice . Jan. 1, 2019 MICHAEL F. CAVANAGH . Jan. 1, 2015 MARY BETH KELLY . Jan. 1, 2019 STEPHEN J. MARKMAN . Jan. 1, 2021 BRIDGET MARY MCCORMACK . Jan. 1, 2021 DAVID F. VIVIANO . Jan. 1, 2015 BRIAN K. ZAHRA . Jan. 1, 2015 www.courts.mi.gov/supremecourt History Under the territorial government of Michigan established in 1805, the supreme court consisted of a chief judge and two associate judges appointed by the President of the United States. -

The Beginning of a New University Presidency Is Usually Associated

1 THE LEADERS AND BEST he beginning of a new university presidency is usually associated Twith the pomp and circumstance of an academic inauguration ceremony. The colorful robes of an academic procession, the familiar strains of ritualistic music, and the presence of distinguished guests and visitors all make for an impressive ceremony, designed to sym- bolize the crowning of a new university leader. Of course, like most senior leadership positions, the university presidency takes many forms depending on the person; the institution; and, perhaps most signi‹cant, the needs of the times. Clearly, as the chief executive of‹cer of an institution with thousands of employees (faculty and staff) and clients (students, patients, sports fans), an annual budget in the billions of dollars, a physical plant the size of a small city, and an in›uence that is frequently global in extent, the management respon- sibilities of the university president are considerable, comparable to those of the CEO of a large, multinational corporation. A university president is also a public leader, with important sym- bolic, political, pastoral, and at times even moral leadership roles, par- ticularly when it comes to representing the institution to a diverse array of external constituencies, such as government, business and industry, prospective donors, the media, and the public at large. The contemporary university is a political tempest in which all the con- 3 4 The View from the Helm tentious issues swirling about our society churn together: for example, civil rights versus racial preference, freedom of speech versus con›ict- ing political ideologies, social purpose versus market-driven cost- effectiveness. -

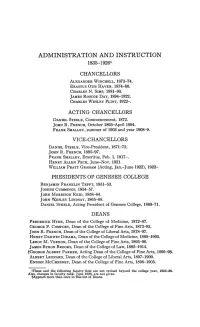

Administration and Instruction 1835-19261

ADMINISTRATION AND INSTRUCTION 1835-19261 CHANCELLORS ALEXANDER WINCHELL, 1873-74. ERASTUS OTIS H~VEN, 1874-80. CHARLES N. SIMS, 1881-93. ]AMES RoscoE DAY, 1894-1922. CHARLES WESLEY FLINT, 1922-. ACTING CHANCELLORS DANIEL STEELE, Commencement, 1872. ]OHN R. FRENCH, October 1893-April1894. FRANK SMALLEY, summer of 1903 and year 1908-9. VICE-CHANCELLORS D~NIEL STEELE, Vice-President, 1871-72. ]OHN R. FRENCH, 1895-97. FRANK SMALLEY, Emeritus, Feb. 1, 1917-. HENRY ALLEN PECK, June-Nov. 1921. WILLIAM PR~TT GRAHAM (Acting, Jan.-June 1922), 1922- :PRESIDENTS OF GENESEE COLLEGE BENJAMIN FRANKLIN TEFFT, 1851-53. JosEPH CuMMINGs, 1854-57. JOHN MoRRISON REID, 1858-64. ]OHN WESLEY LINDSAY, 1865-68. DANIEL STEELE, Acting President of Genesee College, 1869-71. DEANS FREDERICK HYDE, Dean of the College of Medicine, 1872-87. GEORGE F. CoMFORT, Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1873-93. JOHN R. FRENCH, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, 1878-97. HE~RY DARWIN DIDAMA, Dean of the College of Medicine, 1888-1905. LEROY M. VERNON, Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1893-96. ]AMES BYRON BROOKS, Dean of the College of Law, 1895-1914. tGEORGE ALBERT PARKER, Acting Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1896-98. ALBERT LEONARD, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, 1897-1900. ENSIGN McCHESNEY, Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1898-1905. IThese and the following faculty lists are not revised beyond the college year, 1925-26. Also, changes in faculty rank, June 1926, are not given. tAppears more than once in this list of Deans. ADMINISTRATION AND INSTRUCTION-DEANS Io69 FRANK SMALLEY, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts (Acting, Sept. -

The University of Michigan Degrees Conferred by President and Level 1845-2008

The University of Michigan Degrees Conferred by President and Level 1845-2008 Degree Level Graduate Intermediate Graduate Cumulative President Total Bachelor Master Professional Doctor Professional Total GEORGE P. WILLIAMS 36 34 2 - - - 36 President of the Faculty 1845 & 1849 ANDREW TEN BROOK 34 29 5 - - - 70 President of the Faculty 1846 & 1850 DANIEL D. WHEDON 30 20 4 - - 6 100 President of the Faculty 1847 & 1851 J. HOLMES AGNEW 58 25 6 - - 27 158 President of the Faculty 1848 & 1852 HENRY P. TAPPAN 1011 355 143 12 - 501 1169 President of the University Aug. 12, 1852 - June, 1863 ERASTUS OTIS HAVEN 1543 219 124 56 - 1144 2712 President of the University June, 1863 - June, 1869 HENRY S. FRIEZE 1280 346 68 44 2 820 3992 Acting President Aug. 18, 1869 - Aug. 1, 1871 Also June, 1880 - Feb. 1882 & 1887 JAMES B. ANGELL 21040 8041 1056 155 139 11649 25032 President of the University Aug. 1, 1871 - Oct., 1909 HARRY BURNS HUTCHINS 13426 8444 1165 24 174 3619 38458 Acting President 1897-98 & 1909-10 President of the University June, 1910 - July, 1920 MARION LEROY BURTON 8127 5861 919 3 103 1241 46585 President of the Unliversity July, 1920 - Feb.. 1925 ALFRED HENRY LLOYD 1649 1124 183 1 33 308 48234 Acting President Feb. 27, 1925 - Sep. 1, 1925 CLARENCE COOK LITTLE 9338 6090 1568 10 246 1424 57572 President of the University Sept. 10, 1925 - Sept. 1, 1929 ALEXANDER GRANT RUTHVEN 76125 42459 22405 62 2395 8804 133697 President of the University Oct. 1, 1929 - Sep. 1, 1951 Office of the Registrar Report 502 Page 1 of 2 The University of Michigan Degrees Conferred by President and Level 1845-2008 Degree Level Graduate Intermediate Graduate Cumulative President Total Bachelor Master Professional Doctor Professional Total HARLAN H. -

Law School of the University of Michigan

Michlgran Universily Lawo School LAW SCHOOL BUILDING. LAW SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN. BY HENRY WADE ROGERS, Dean of the Department of Law of ttheUniversity of Michigan. ception of the period in which he served the HEthe University two largest of Michiganuniversities is inone theof country as Minister to China, and more re- United States, and this position it has at- cently while he was acting as a member of tained within a comparatively few years. In the Fishery Commission intrusted with the June, 1887, it celebrated its semi-centennial ; delicate duty of attempting an adjustment of and the University Calendar this year issued the difficulties existing between the United shows a Faculty roll of one hundred and States and Great Britain. He has the satis- eight professors, instructors, and qssistants, faction of knowing that during his admin- as well as the names of eighteen hundred istration the University of Michigan has and eighty-two students. Harvard Univer- grown from an institution with eleven hun- sity, founded in 1636, and the oldest institu- dred and ten students and a Faculty roll of tion of learning in the country, celebrating thirty-six, to its present proportions. its two hundred and fiftieth anniversary The founders of the State of Michigan in November, i886, leads it in numbers and their descendants have kept in sacred by only seventeen students. In 1871 the remembrance that memorable article in the Hon. James 13. Angell, LL.D., became Ordinance of 1787, which proclaims that, President of the University of Michigan, "religion, morality, and knowledge being and from that time to the present has con- necessary to good government and the hap- tinued to act in that capacity, with the ex- piness of mankind, schools and the means 26 HeinOnline -- 1 Green Bag 189 1889 I90 The Green Bag. -

Fanfare Yes? It’S Time! Join YOUR University of in THIS ISSUE: Michigan a Very Special Opportunity for Michigan Bands Students & Alumni

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIG AN BAND ALUMNI ASSOCIATION: YESTERDAY, TODAY, AN D T O M O R R O W Summer 2015 Blast From The Past Issue Volume 68, Issue 1 WELCOME! Were YOU a member of any University of Michigan Band? fanfare Yes? It’s time! Join YOUR University of IN THIS ISSUE: Michigan A Very Special Opportunity for Michigan Bands Students & Alumni ........ 2 Band Alumni Association! We Are Wolverines! by Grace Wolfe, Class of 2015......................................... 3 For those who leave Jennifer Chuang Wins Fulbright Grant .................................................... 5 Michigan and its bands, but for whom Michigan's bands Calling All KKY / TBS Alumni—Brunch on Homecoming Weekend............ 5 never leave, this is where 2015/16 Michigan Bands Concerts from The Directors ................................. 6 you belong: University of Michigan Band Why Be A Member of UMBAA? .............................................................. 8 Alumni Association 2015 ChampionSHEEP! by David Aguilar ..................................................... 9 Strengthen your connection Join or Renew Your Membership—Annual Member Registration ............ 10 to the Michigan Bands and UMBAA Website LAUNCHED! by Jason Townsend, Webmaster ....................... 12 lend your support for the UMBAA Merchandise on Cafepress.com ................................................. 12 band program, current students and alumni by Blast From The Past 2015—Information & Incredibly Tentative Itinerary . 13 becoming a member. Membership dues are $20 UMBAA Annual