I I I I I I I I I I I I I 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENROLLMENT CORRECTIONS-S. 2834 Resolved by the Senate (The House of Representatives Concurring), That in the Enrollment of the Bill (S

104 STAT. 5184 CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—OCT. 26, 1990 Whereas it is proper and timely for the Congress of the United States of America to acknowledge, on the occasion of the impend ing one hundredth anniversary of the event, the historic signifi cance of the Massacre at Wounded Knee Creek, to express its deep regret to the Sioux people and in particular to the descendants of the victims and survivors for this terrible tragedy, and to support the reconciliation efforts of the State of South Dakota and the Wounded Knee Survivors Association: Now, therefore, be it Resolved by the Senate (the House of Representatives concurring). That— (1) the Congress, on the occasion of the one hundredth anniversary of the Wounded Knee Massacre of December 29, 1890, hereby acknowledges the historical significance of this event as the last armed conflict of the Indian wars period resulting in the tragic death and injury of approximately 350- 375 Indian men, women, and children of Chief Big Foot's band of Minneconjou Sioux and hereby expresses its deep regret on behalf of the United States to the descendants of the victims and survivors and their respective tribal communities; (2) the Congress also hereby recognizes and commends the efforts of reconciliation initiated by the State of South Dakota and the Wounded Knee Survivors Association and expresses its support for the establishment of a suitable and appropriate Memorial to those who were so tragically slain at Wounded Knee which could inform the American public of the historic significance of the events at Wounded Knee and accurately portray the heroic and courageous campaign waged by the Sioux people to preserve and protect their lands and their way of life during this period; and (3) the Congress hereby expresses its commitment to acknowl edge and learn from our history, including the Wounded Knee Massacre, in order to provide a proper foundation for building an ever more humane, enlightened, and just society for the future. -

Brf Public Schools

BRF PUBLIC SCHOOLS HISTORY CURRICULUM RELATED TO AMERICAN INDIAN STUDIES GRADES 8-12 COMPONENT The following materials represent ongoing work related to the infusion of American Indian history into the History curriculum of the Black River Falls Public Schools. Our efforts in this area have been ongoing for over 20 years and reflect the spirit of Wisconsin Act 31. SEPTEMBER 2011 UPDATE Paul S Rykken Michael Shepard US History and Politics US History BRFHS BRF Middle School Infusion Applications 1 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW The Infusion Task Force was established in December of 2009 for the purpose of improving our efforts regarding the infusion of American Indian history and cultural awareness throughout the BRF Public School K-12 Social Studies Curriculum. This action occurred within the context of several other factors, including the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding between the Ho-chunk Nation and the School District and the establishment of a Ho-chunk language offering at BRFHS. Our infusion efforts go back to the early 1990s and were originally spurred by the Wisconsin Legislature’s passage of Act 31 related to the teaching of Native American history and culture within Wisconsin’s public schools. The following link will take you to a paper that more fully explains our approach since the early 1990s: http://www.brf.org/sites/default/files/users/u123/InfusionUpdate09.pdf THE 8-12 COMPONENT As with any curriculum-related project, what follows is not the final word. We do our work in an ever- changing environment. The lessons and information included here, however, reflect the most recent (and complete) record of what we are doing within our 8-12 curriculum. -

Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in English of Native American Origin Found Within

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Indian origin names, were eventually shortened to one-word names, making a few indistinguishable from names of non-Indian origin. Name Categories: Personal and family names of Indian origin contrast markedly with names of non-Indian Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in origin. English of Native American Origin 1. Personal and family names from found within Marquette University Christian saints (e.g. Juan, Johnson): Archival Collections natives- rare; non-natives- common 2. Family names from jobs (e.g. Oftentimes names of Native Miller): natives- rare; non-natives- American origin are based on objects common with descriptive adjectives. The 3. Family names from places (e.g. following list, which is not Rivera): natives- rare; non-native- comprehensive, comprises common approximately 1,000 name variations in 4. Personal and family names from English found within the Marquette achievements, attributes, or incidents University archival collections. The relating to the person or an ancestor names originate from over 50 tribes (e.g. Shot with two arrows): natives- based in 15 states and Canada. Tribal yes; non-natives- yes affiliations and place of residence are 5. Personal and family names from noted. their clan or totem (e.g. White bear): natives- yes; non-natives- no History: In ancient times it was 6. Personal or family names from customary for children to be named at dreams and visions of the person or birth with a name relating to an animal an ancestor (e.g. Black elk): natives- or physical phenominon. Later males in yes; non-natives- no particular received names noting personal achievements, special Tribes/ Ethnic Groups: Names encounters, inspirations from dreams, or are expressed according to the following physical handicaps. -

Wind Through the Buffalo Grass: a Lakota Story Cycle Paul A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 2008 Wind Through the Buffalo Grass: A Lakota Story Cycle Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Wind Through the Buffalo Grass: A Lakota Story Cycle" (2008). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 51. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/51 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Fiction I Historical History I Native Ameri("an Wind Through the Buffalo Grass: A Lakota Story Cycle is a narrative history of the Pine Ridge Lakota tribe of South Dakota, following its history from 1850 to the present day through actual historical events and through the stories of four fictional Lakota children, each related by descent and separated from one another by two generations. The ecology of the Pine Ridge region, especially its mammalian and avian wildlife, is woven into the stories of the children. 111ustrated by the author, the book includes drawings of Pine Ridge wildlife, regional maps, and Native American pictorial art. Appendices include a listing of important Lakota words, and checklists of mammals and breeding birds of the region. Dr. Paul A. Johnsgard is foundation professor of biological sciences emeritus of the University of Nebraska-lincoln. -

2 Kansas History Northern Cheyenne Warrior Ledger Art: Captivity Narratives of Northern Cheyenne Prisoners in 1879 Dodge City

Ledger art made by Northern Cheyenne Chief Wild Hog in 1879. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 35 (Spring 2012): 2–25 2 Kansas History Northern Cheyenne Warrior Ledger Art: Captivity Narratives of Northern Cheyenne Prisoners in 1879 Dodge City by Denise Low and Ramon Powers n February 17, 1879, Ford County Sheriff W. D. “Bat” Masterson arrived at the Dodge City train depot with seven Northern Cheyenne men as prisoners. The State of Kansas was charging them with forty murders in what would later be identified as the last “Indian raid” in Kansas. In 1877 the government had ordered all Northern Cheyennes to move to Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, which most of the tribe had found intolerable. A group of about 350 Northern Cheyenne men, women, and children escaped in September 1878. They Ofought skirmishes and raided throughout western Kansas, and eventually split into two groups—one under leadership of Little Wolf and one under Dull Knife (or Morning Star). The Little Wolf band eluded the U.S. Army, but 149 of those under Dull Knife were finally imprisoned at Camp Robinson in Nebraska.1 While army officials determined their fate, they remained in custody into the winter. They attempted to break out of captivity on January 9, 1879, and, after military reprisal, perhaps less than fifteen men remained alive. A few who escaped sought refuge at the Pine Ridge Agency in South Dakota. Military authorities sent most of the survivors back to Indian Territory except for seven men who were destined for trial in Kansas. The seven men arriving in Dodge City, a remnant of the Dull Knife fighting force, would face Ford County charges.2 Denise Low received a National Endowment for the Humanities Faculty Fellowship for completion of this article. -

Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone Land Use in Northern Nevada: a Class I Ethnographic/Ethnohistoric Overview

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Land Management NEVADA NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Ginny Bengston CULTURAL RESOURCE SERIES NO. 12 2003 SWCA ENVIROHMENTAL CON..·S:.. .U LTt;NTS . iitew.a,e.El t:ti.r B'i!lt e.a:b ~f l-amd :Nf'arat:1.iern'.~nt N~:¥G~GI Sl$i~-'®'ffl'c~. P,rceP,GJ r.ei l l§y. SWGA.,,En:v,ir.e.m"me'Y-tfol I €on's.wlf.arats NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Submitted to BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Nevada State Office 1340 Financial Boulevard Reno, Nevada 89520-0008 Submitted by SWCA, INC. Environmental Consultants 5370 Kietzke Lane, Suite 205 Reno, Nevada 89511 (775) 826-1700 Prepared by Ginny Bengston SWCA Cultural Resources Report No. 02-551 December 16, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................v List of Tables .................................................................v List of Appendixes ............................................................ vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................1 CHAPTER 2. ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW .....................................4 Northern Paiute ............................................................4 Habitation Patterns .......................................................8 Subsistence .............................................................9 Burial Practices ........................................................11 -

Chapter 3 Arapaho Ethnohistory and Historical

Chapter 3 Arapaho Ethnohistory and Historical Ethnography ______________________________________________________ 3.1 Introduction The Arapaho believe they were the first people created on earth. The Arapaho called themselves, the Hinanae'inan, "Our Own Kind of People.”1 After their creation, Arapaho tradition places them at the earth's center. The belief in the centrality of their location is no accident. Sociologically, the Arapaho occupied the geographical center among the five ethnic distinct tribal-nations that existed prior to the direct European contact.2 3.2 Culture History and Territory Similar to many other societies, the ethnic formation of the Arapaho on the Great Plains into a tribal-nation was a complex sociological process. The original homeland for the tribe, according to evidence, was the region of the Red River and the Saskatchewan River in settled horticultural communities. From this original homeland various Arapaho divisions gradually migrated southwest, adapting to living on the Great Plains.3 One of the sacred objects, symbolic of their life as horticulturalists, that they carried with them onto the Northern Plains is a stone resembling an ear of corn. According to their oral traditions, the Arapaho were composed originally of five distinct tribes. 4 Arapaho elders remember the Black Hills country, and claim that they once owned that region, before moving south and west into the heart of the Great Plains. By the early nineteenth century, the Arapaho positioned themselves geographically from the two forks of the Cheyenne River, west of the Black Hills southward to the eastern front 87 of the central Rocky Mountains at the headwaters of the Arkansas River.5 By 1806 the Arapaho formed an alliance with the Cheyenne to resist against further intrusion west by the Sioux beyond the Missouri River. -

![HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY COMMEMORATION [S Con. Res. 153]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2188/hundredth-anniversary-commemoration-s-con-res-153-472188.webp)

HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY COMMEMORATION [S Con. Res. 153]

CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—OCT. 25,1990 104 STAT. 5183 violence reveals that violent tendencies may be passed on from one generation to the next; Whereas witnessing an aggressive parent as a role model may communicate to children that violence is an acceptable tool for resolving marital conflict; and Wheregis few States have recognized the interrelated natui-e of child custody and battering and have enacted legislation that allows or requires courts to consider evidence of physical abuse of a spouse in child custody cases: Now, therefore, be it Resolved by the House of Representatives (the Senate concurring), SECTION 1. It is the sense of the Congress that, for purposes of determining child custody, credible evidence of physical abuse of a spouse should create a statutory presumption that it is detrimental to the child to be placed in the custody of the abusive spouse. SEC. 2. This resolution is not intended to encourage States to prohibit supervised visitation. Agreed to October 25, 1990. WOUNDED KNEE CREEK MASSACRE—ONE- oct. 25.1990 HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY COMMEMORATION [s con. Res. 153] Whereas, in order to promote racial harmony and cultural under standing, the Grovernor of the State of South Dakota has declared that 1990 is a Year of Reconciliation between the citizens of the State of South Dakota and the member bands of the Great Sioux Nation; Whereas the Sioux people who are descendants of the victims and survivors of the Wounded Knee Massacre have been striving to reconcile and, in a culturally appropriate manner, to bring to an end -

Arapaho Gender in Time

Presidential Lecture: Wives and Husbands: Arapaho Gender in Time Loretta Fowler Abstract. This essay examines the lives of four Arapahos whose experiences are broadly representative of the life-career patterns of their cohorts during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It argues that in the American encounter, individuals and groups challenged both American and Arapaho ideas and practices associated with age and gender. Comparison of experiences between and within cohorts shows age- and gender-based strategies, including the “partnering” dimen- sion of gender relations most evident in the wife-husband relation. These multiple strategies shaped Arapaho history. If you were to approach an Arapaho camp on their Oklahoma reservation in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, you would see hundreds of white tents along a stream and beside most of the tents, a wagon and a patch of white. Upon closer inspection, the patches of white are groups of relatively motionless chickens. The chickens are tethered like horses were before the reservation days. Women are washing clothes in the stream with soap weed. Little boys are playing baseball. Everywhere, running free, are packs of barking dogs. Meanwhile, the band headmen are in the Indian agent’s office negotiating how many days the people can camp together away from their home places.1 Arapahos and their Cheyenne allies arrived on the reservation in 1870. Reservation life meant close supervision and penalties for deviation from government policy. In the early twentieth century, they had only small home places because most of their land was leased to settlers. But periodically, the Arapahos came together in large camps and held councils and ceremonies where decision making and the exercise of authority took place. -

Massacre on the Plains: a Better Way to Conceptualize

MASSACRE ON THE PLAINS: A BETTER WAY TO CONCEPTUALIZE GENOCIDE ON AMERICAN SOIL by KEATON J KELL A THESIS Presented to the Conflict and Dispute Resolution Program and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science June 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Keaton J Kell Title: Massacre on the Plains: A Better Way to Conceptualize Genocide on American Soil This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in the Conflict and Dispute Resolution Program by: Michael Moffitt Chair Keith Eddins Core Member and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Keaton J Kell iii THESIS ABSTRACT Keaton J Kell Master of Science Conflict and Dispute Resolution Program June 2017 Title: Massacre on the Plains: A Better Way to Conceptualize Genocide on American Soil This thesis examines the massacres of the Plains Indian Wars in the United States (1851-1890) and how they relate to contemporary theories of genocide. By using the Plains Indian Wars as a case study, a critique can be made of theories which inform predictive models and genocide policy. This thesis analyzes newspaper articles, histories, congressional investigations, presidential speeches, and administrative policies surrounding the four primary massacres perpetrated by the United States during this time. An ideology of racial superiority and fears of insecurity, impurity, and insurgency drove the actions of the white settler-colonialists and their military counterparts. -

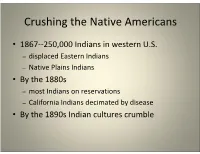

Crushing the Native Americans

Crushing the Native Americans • 1867--250,000 Indians in western U.S. – displaced Eastern Indians – Native Plains Indians • By the 1880s – most Indians on reservations – California Indians decimated by disease • By the 1890s Indian cultures crumble Essential Questions 1) What motivated Americans from the east to move westward? 2) How did American expansion westward affect the American Indians? 3) How was American “identity” forged through westward expansion? Which picture best represents America? What affects our perception of American identity? Life of the Plains Indians: Political Organization • Plains Indians nomadic, hunt buffalo – skilled horsemen – tribes develop warrior class – wars limited to skirmishes, "counting coups" • Tribal bands governed by chief and council • Loose organization confounds federal policy Life of the Plains Indians: Social Organization • Sexual division of labor – men hunt, trade, supervise ceremonial activities, clear ground for planting – women responsible for child rearing, art, camp work, gardening, food preparation • Equal gender status common – kinship often matrilineal – women often manage family property Misconceptions / Truths of Native Americans Misconceptions Truths • Not all speak the same • Most did believe land belonged language or have the same to no one (no private property) traditions • Reservation lands were • Not all live on reservations continually taken away by the • Tribes were not always government unified • Many relied on hunting as a • Most tribes were not hostile way of life (buffalo) • Most tribes put a larger stake on honor rather than wealth Culture of White Settlers • Most do believe in private property • A strong emphasis on material wealth (money) • Few rely on hunting as a way of life; most rely on farming • Many speak the same language and have a similar culture What is important about the culture of white settlers in comparison to the culture of the American Indians? What does it mean to be civilized? “We did not ask you white men to come here. -

OUT HERE, WE HAVE a STORY to TELL. This Map Will Lead You on a Historic Journey Following the Movements of Lt

OUT HERE, WE HAVE A STORY TO TELL. This map will lead you on a historic journey following the movements of Lt. Col. Custer and the 7th Calvary during the days, weeks and months leading up to, and immediately following, the renowned Battle of Little Bighorn were filled with skirmishes, political maneuvering and emotional intensity – for both sides. Despite their resounding victory, the Plains Indians’ way of life was drastically, immediately and forever changed. Glendive Stories of great heroism and reticent defeat continue to reverberate through MAKOSHIKA STATE PARK 253 the generations. Yet the mystique remains today. We invite you to follow the Wibaux Trail to The Little Bighorn, to stand where the warriors and the soldiers stood, 94 to feel the prairie sun on your face and to hear their stories in the wind. 34 Miles to Theodore Terry Roosevelt Fallon National Park 87 12 Melstone Ingomar 94 PIROGUE Ismay ISLAND 12 12 Plevna Harlowton 1 Miles City Baker Roundup 12 89 12 59 191 Hysham 12 4 10 2 12 14 13 11 9 3 94 Rosebud Lavina Forsyth 15 332 447 16 R MEDICINE E ER 39 IV ROCKS IV R R 5 E NE U STATE PARK Broadview 87 STO 17 G OW Custer ON L T NORTH DAKOTA YE L 94 6 59 Ekalaka CUSTER GALLATIN NF 18 7 332 R E 191 IV LAKE Colstrip R MONTANA 19 Huntley R 89 Big Timber ELMO E D Billings W 447 O 90 384 8 P CUSTER Reed Point GALLATIN Bozeman Laurel PICTOGRAPH Little Bighorn Battlefield NATIONAL 90 CAVES Hardin 20 447 FOREST Columbus National Monument Ashland Crow 212 Olive Livingston 90 Lame Deer WA Agency RRIO SOUTH DAKOTA R TRA 212 IL 313 Busby