Massacre on the Plains: a Better Way to Conceptualize

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENROLLMENT CORRECTIONS-S. 2834 Resolved by the Senate (The House of Representatives Concurring), That in the Enrollment of the Bill (S

104 STAT. 5184 CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—OCT. 26, 1990 Whereas it is proper and timely for the Congress of the United States of America to acknowledge, on the occasion of the impend ing one hundredth anniversary of the event, the historic signifi cance of the Massacre at Wounded Knee Creek, to express its deep regret to the Sioux people and in particular to the descendants of the victims and survivors for this terrible tragedy, and to support the reconciliation efforts of the State of South Dakota and the Wounded Knee Survivors Association: Now, therefore, be it Resolved by the Senate (the House of Representatives concurring). That— (1) the Congress, on the occasion of the one hundredth anniversary of the Wounded Knee Massacre of December 29, 1890, hereby acknowledges the historical significance of this event as the last armed conflict of the Indian wars period resulting in the tragic death and injury of approximately 350- 375 Indian men, women, and children of Chief Big Foot's band of Minneconjou Sioux and hereby expresses its deep regret on behalf of the United States to the descendants of the victims and survivors and their respective tribal communities; (2) the Congress also hereby recognizes and commends the efforts of reconciliation initiated by the State of South Dakota and the Wounded Knee Survivors Association and expresses its support for the establishment of a suitable and appropriate Memorial to those who were so tragically slain at Wounded Knee which could inform the American public of the historic significance of the events at Wounded Knee and accurately portray the heroic and courageous campaign waged by the Sioux people to preserve and protect their lands and their way of life during this period; and (3) the Congress hereby expresses its commitment to acknowl edge and learn from our history, including the Wounded Knee Massacre, in order to provide a proper foundation for building an ever more humane, enlightened, and just society for the future. -

Life, Letters and Travels of Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, S.J., 1801-1873

Si>xm §i <•}; L I E) R.AR.Y OF THE U N IVERSITY or ILLINOIS B V.4 iLin^MSiflsiiK^^tt Vil'r^i?!-.;?;^ :;.v.U;i Life, Letters and Travels of Father De Smet among the North American Indians. »*> ^ 9mniu:^ um REV. PIERRE-JEAN DE SMET, S. J. LIFE, LETTERS AND TRAVELS OF Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, S. J. 1801-1873 Missionary Labors and Adventures among the Wild Tribes of the North American Indians, Embracing Minute Description of Their Manners, Customs, Games, Modes of Warfare and Torture, Legends, Tradition, etc., All from Personal Observations Made during Many Thousand Miles of Travel, with Sketches of the Country from St. Louis to Puget Sound and the Altrabasca Edited from the original unpublished manuscript Journals and Letter Books and from his Printed Works with Historical, Geographical, Ethnological and other Notes; Also a Life of Father De Smet MAP AND ILLUSTRATIONS HIRAM MARTIN CHITTENDEN Major, Corps of Engineers, U. S. A. AND ALFRED TALBOT RICHARDSON FOUR VOLUMES VOL. IV NEW YORK .'W*» FRANCIS P. HARPER i^^' 1905 •if* O^*^^ t^ J Copyright, 1904, BY FRANCIS P. HARPER All rights reserved CONTENTS OF VOLUME IV. CHAPTER XIV. PACE. Miscellaneous Letters Relating to the Indians . 1213-1227 PART VIII. MISSIONARY WORK AMONG THE INDIANS. CHAPTER I. The Flathead and other Missions 1228-1249 CHAPTER II. Letters from the Resident Missionaries .... 1250-1261 CHAPTER IIL Tributes to the Flatheads and other Tribes . 1262-1278 CHAPTER IV. Plans for a Sioux Mission 1279-1304 CHAPTER V. Miscellaneous Missionary Notes 1305-1344 PART IX. MISCELLANEOUS WRITINGS. -

Indian Trust Asset Appendix

Platte River Endangered Species Recovery Program Indian Trust Asset Appendix to the Platte River Final Environmental Impact Statement January 31,2006 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Denver, Colorado TABLE of CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 The Recovery Program and FEIS ........................................................................................ 1 Indian trust Assets ............................................................................................................... 1 Study Area ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Indicators ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Methods ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Background and History .................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 Overview - Treaties, Indian Claims Commission and Federal Indian Policies .................. 5 History that Led to the Need for, and Development of Treaties ....................................... -

Wind Through the Buffalo Grass: a Lakota Story Cycle Paul A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 2008 Wind Through the Buffalo Grass: A Lakota Story Cycle Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Wind Through the Buffalo Grass: A Lakota Story Cycle" (2008). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 51. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/51 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Fiction I Historical History I Native Ameri("an Wind Through the Buffalo Grass: A Lakota Story Cycle is a narrative history of the Pine Ridge Lakota tribe of South Dakota, following its history from 1850 to the present day through actual historical events and through the stories of four fictional Lakota children, each related by descent and separated from one another by two generations. The ecology of the Pine Ridge region, especially its mammalian and avian wildlife, is woven into the stories of the children. 111ustrated by the author, the book includes drawings of Pine Ridge wildlife, regional maps, and Native American pictorial art. Appendices include a listing of important Lakota words, and checklists of mammals and breeding birds of the region. Dr. Paul A. Johnsgard is foundation professor of biological sciences emeritus of the University of Nebraska-lincoln. -

COLORADO MAGAZINE Published by the State Historical Society of Colorado

THE COLORADO MAGAZINE Published by The State Historical Society of Colorado VO L. VIII Denver, Colorado, May, 1931 No. 3 History of Fort Lewis, Colorado MARY c. AYRES* At the base of the La Plata Mountains, twelve miles west of Durango, was located the military post of Fort Lewis. During frontier days this was an important place not only in military operations a!Ild Indian fights but in the social life of the region as well. Here were stationed not only dashing young graduates of West Point but also many officers who had gained fame on the battlefields of the Civil War. The fort owed its existence to the warfare between the Indians and whites and was abatndoned when the need for protection was no longer felt. The first issue of the La Plata Miner, published in Silverton on Saturday, July 10, 1875, contained an editorial written by the editor, John R. Curry, on the need for the establishment of a mili tary post in the Animas valley. Though two years earlier the Utes had signed the Brunot treaty, relinquishing their rights to the San Juan mining region, they still roamed at large through the country, becoming increasingly hostile as the white settlers in creased in number and more land was taken up. As the Indians lived largely by hunting they knew of no other way to exist and realized that as more land was occupied by the immense herds of cattle which were being brought in, game would disappear and their food supply be diminished. Their ideal was to preserve their hunting grounds intact while periodically visiting an agency to receive their raLons. -

Guide for a Field Conference on the Tertiary and Pleistocene of Nebraska

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences of 1941 GUIDE FOR A FIELD CONFERENCE ON THE TERTIARY AND PLEISTOCENE OF NEBRASKA C. Bertrand Schultz University of Nebraska-Lincoln Thompson M. Stout University of Nebraska-Lincoln Alvin Leonard Lugn University of Nebraska-Lincoln M. K. Elias University of Nebraska F. W. Johnson University of Nebraska See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Schultz, C. Bertrand; Stout, Thompson M.; Lugn, Alvin Leonard; Elias, M. K.; Johnson, F. W.; and Skinner, M. F., "GUIDE FOR A FIELD CONFERENCE ON THE TERTIARY AND PLEISTOCENE OF NEBRASKA" (1941). Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. 370. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub/370 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors C. Bertrand Schultz, Thompson M. Stout, Alvin Leonard Lugn, M. K. Elias, F. W. Johnson, and M. F. Skinner This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ geosciencefacpub/370 GUIDE FOR A FIELD CONFERENCE ON THE TERTIARY AND PLEISTOCENE OF NEBRASKA By Co Be Schultz and To Mo Stout In collaboration with A. Lo Lugn Tvle Ko Elias F, Wo Johnson M- Fo Skinner Dedicated to Dr. -

FT. LYON SUPPORTIVE RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITY ANNUAL REPORT: JULY 2015–JUNE 2016 Produced by the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless

FT. LYON SUPPORTIVE RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITY ANNUAL REPORT: JULY 2015–JUNE 2016 Produced by the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Fort Lyon Supportive Residential Community provides transitional housing and supportive services to homeless and at-risk individuals from across Colorado, with a priority on serving homeless veterans. Situated on 552 acres in the Lower Arkansas Valley, the Fort Lyon initiative is a state-wide collaborative led by the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, Bent County and the Colorado Department of Local Affairs. Under the direction of Governor John Hickenlooper, the former Veterans Administration hospital has been successfully repurposed, recently completing three years of program operation serving nearly 800 of Colorado’s most vulnerable citizens. In Fiscal Year 2016, Fort Lyon served 432 individuals, 88 of those being veterans. Fort Lyon residents represented a large portion of the state of Colorado, with the highest representative populations coming from Denver, El Paso, Jefferson, Arapahoe and Pueblo counties. Most residents arrived on campus with no cash income and multiple health conditions after experiencing homelessness for more than a year. Through person-centered and strengths-based case management, recovery-oriented peer support, direct access to post-secondary education, vocational training, and employment, the Fort Lyon program realized a 91% average monthly retention rate within its safe, trauma-informed environment. Eighty-three percent of residents participated in recovery-based support groups including New Beginnings early drug and alcohol education, Life Ring and Alcohol/Narcotics Anonymous. Through this cross-section of services and opportunities, the average resident stayed engaged in the Fort Lyon program for over 9 months, increasing their odds of obtaining long-term sobriety.1 Among those residents who left Fort Lyon in Fiscal Year 2016, 63% moved on to permanent or transitional housing destinations, with 40% securing permanent housing. -

![HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY COMMEMORATION [S Con. Res. 153]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2188/hundredth-anniversary-commemoration-s-con-res-153-472188.webp)

HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY COMMEMORATION [S Con. Res. 153]

CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—OCT. 25,1990 104 STAT. 5183 violence reveals that violent tendencies may be passed on from one generation to the next; Whereas witnessing an aggressive parent as a role model may communicate to children that violence is an acceptable tool for resolving marital conflict; and Wheregis few States have recognized the interrelated natui-e of child custody and battering and have enacted legislation that allows or requires courts to consider evidence of physical abuse of a spouse in child custody cases: Now, therefore, be it Resolved by the House of Representatives (the Senate concurring), SECTION 1. It is the sense of the Congress that, for purposes of determining child custody, credible evidence of physical abuse of a spouse should create a statutory presumption that it is detrimental to the child to be placed in the custody of the abusive spouse. SEC. 2. This resolution is not intended to encourage States to prohibit supervised visitation. Agreed to October 25, 1990. WOUNDED KNEE CREEK MASSACRE—ONE- oct. 25.1990 HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY COMMEMORATION [s con. Res. 153] Whereas, in order to promote racial harmony and cultural under standing, the Grovernor of the State of South Dakota has declared that 1990 is a Year of Reconciliation between the citizens of the State of South Dakota and the member bands of the Great Sioux Nation; Whereas the Sioux people who are descendants of the victims and survivors of the Wounded Knee Massacre have been striving to reconcile and, in a culturally appropriate manner, to bring to an end -

SPIDER in the RIVER: a COMPARATIVE ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY of the IMPACT of the CACHE LA POUDRE WATERSHED on CHEYENNES and EURO- AMERICANS, 1830-1880 John J

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, History, Department of Department of History Spring 4-21-2015 SPIDER IN THE RIVER: A COMPARATIVE ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY OF THE IMPACT OF THE CACHE LA POUDRE WATERSHED ON CHEYENNES AND EURO- AMERICANS, 1830-1880 John J. Buchkoski University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Buchkoski, John J., "SPIDER IN THE RIVER: A COMPARATIVE ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY OF THE IMPACT OF THE CACHE LA POUDRE WATERSHED ON CHEYENNES AND EURO-AMERICANS, 1830-1880" (2015). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 83. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/83 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SPIDER IN THE RIVER: A COMPARATIVE ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY OF THE IMPACT OF THE CACHE LA POUDRE WATERSHED ON CHEYENNES AND EURO-AMERICANS, 1830-1880 By John J. Buchkoski A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor Katrina L. Jagodinsky Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2015 SPIDER IN THE RIVER: A COMPARATIVE ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY OF THE IMPACT OF THE CACHE LA POUDRE WATERSHED ON CHEYENNES AND EURO-AMERICANS, 1830-1880 John Buchkoski, M.A. -

COLORADO MAGAZINE Published Quarterly by the State H Istor Ical Society of Colorado

THE COLORADO MAGAZINE Published Quarterly by The State H istor ical Society of Colorado Vol. XXX l l Denver, Colorado, October, 1955 Number 4 Blood On The Moon By T. D. LIVINGSTON* In August 1878, a band of Ute Indians, Piah, Washington, and Captain ,Jack and others, went on the plains east of Denver on a buffalo hunt. 'l'hey got into some trouble with a man named McLane1 and killed him. The Indians then left there and started back to the ·white River Reservation, Colorado. On their way back they got some whiskey and got mean. \Vent into C. I-I. Hook 's meadow that was fenced, tore the fence down and camped in the meadow. The stocktender tried to get them out. They said: "No, this Indians' land. '' The stocktender then went to Hot Sulphur Springs and got Sheriff Marker. The Sheriff got a posse of eighteen men, went up to the stage station to get them out. This was near where the town of Fraser is now located, eighteen miles from Hot Sulphur Springs. There \ YaS a man (Big Frank) in the bunch who previously had been in North Park prospecting with a party of seven. Colo- *In 1934 T. D. Livingston of Rawlins, Wyoming, wrote an eye-witness account of the Ute Indian troubles in l\Iiddle Park, Colorado, during the summer of 1878. Ue sent the story to l\iiss Mildred Mcintosh of Slater, Colorado, the daugh ter of Hobert l\Iclntosh, 11ioneer ranchrnan. miner and merchant of the Hahn's Peak and Little Snake river areas. -

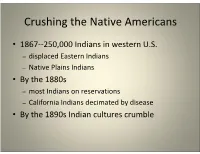

Crushing the Native Americans

Crushing the Native Americans • 1867--250,000 Indians in western U.S. – displaced Eastern Indians – Native Plains Indians • By the 1880s – most Indians on reservations – California Indians decimated by disease • By the 1890s Indian cultures crumble Essential Questions 1) What motivated Americans from the east to move westward? 2) How did American expansion westward affect the American Indians? 3) How was American “identity” forged through westward expansion? Which picture best represents America? What affects our perception of American identity? Life of the Plains Indians: Political Organization • Plains Indians nomadic, hunt buffalo – skilled horsemen – tribes develop warrior class – wars limited to skirmishes, "counting coups" • Tribal bands governed by chief and council • Loose organization confounds federal policy Life of the Plains Indians: Social Organization • Sexual division of labor – men hunt, trade, supervise ceremonial activities, clear ground for planting – women responsible for child rearing, art, camp work, gardening, food preparation • Equal gender status common – kinship often matrilineal – women often manage family property Misconceptions / Truths of Native Americans Misconceptions Truths • Not all speak the same • Most did believe land belonged language or have the same to no one (no private property) traditions • Reservation lands were • Not all live on reservations continually taken away by the • Tribes were not always government unified • Many relied on hunting as a • Most tribes were not hostile way of life (buffalo) • Most tribes put a larger stake on honor rather than wealth Culture of White Settlers • Most do believe in private property • A strong emphasis on material wealth (money) • Few rely on hunting as a way of life; most rely on farming • Many speak the same language and have a similar culture What is important about the culture of white settlers in comparison to the culture of the American Indians? What does it mean to be civilized? “We did not ask you white men to come here. -

Iowner of Property

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ______TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS_____ NAME HISTORIC Ash Hollow Historic District_____________________________ AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Three miles -southwest of Lewellen _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Lewellen VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE 031 Garden 069 CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —^DISTRICT —PUBLIC —^OCCUPIED X-AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL 4KPARK —STRUCTURE X_BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL -^TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Multiple ownership______ STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC. County Clerk STREET & NUMBER Garden County Courthouse CITY, TOWN STATE Oshkosh Nebraska (REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Preservation in Nebraska DATE 1971 —FEDERAL _2STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY, TOWN STATE 1500 R Street Lincoln Nebraska —EXCELLENT JSDETERIORATED -.UNALTERED .XGOOD —RUINS —ALTERED —FAIR _UNEXPOSED Ash Hollow Historic District is located three miles County, Nebraska. Ash Hollow District measures roughly four miles in length, 1,000 feet wide between its gateway cliffs at the North Platte River up to 2,000 feet rim to rim w£th an average depth of about 250 feet (Mattes 1969: 281). Ash Hollow was one of the more notable landmarks along the Oregon-California Overland Trail. Here was located fresh water flowing from springs, a fairly constant source of firewood (it must be remembered that this is quite remarkable for the tree less plains) , and grasses.for grazing for pioneer livestock.