· ...-- Wounded Knee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENROLLMENT CORRECTIONS-S. 2834 Resolved by the Senate (The House of Representatives Concurring), That in the Enrollment of the Bill (S

104 STAT. 5184 CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—OCT. 26, 1990 Whereas it is proper and timely for the Congress of the United States of America to acknowledge, on the occasion of the impend ing one hundredth anniversary of the event, the historic signifi cance of the Massacre at Wounded Knee Creek, to express its deep regret to the Sioux people and in particular to the descendants of the victims and survivors for this terrible tragedy, and to support the reconciliation efforts of the State of South Dakota and the Wounded Knee Survivors Association: Now, therefore, be it Resolved by the Senate (the House of Representatives concurring). That— (1) the Congress, on the occasion of the one hundredth anniversary of the Wounded Knee Massacre of December 29, 1890, hereby acknowledges the historical significance of this event as the last armed conflict of the Indian wars period resulting in the tragic death and injury of approximately 350- 375 Indian men, women, and children of Chief Big Foot's band of Minneconjou Sioux and hereby expresses its deep regret on behalf of the United States to the descendants of the victims and survivors and their respective tribal communities; (2) the Congress also hereby recognizes and commends the efforts of reconciliation initiated by the State of South Dakota and the Wounded Knee Survivors Association and expresses its support for the establishment of a suitable and appropriate Memorial to those who were so tragically slain at Wounded Knee which could inform the American public of the historic significance of the events at Wounded Knee and accurately portray the heroic and courageous campaign waged by the Sioux people to preserve and protect their lands and their way of life during this period; and (3) the Congress hereby expresses its commitment to acknowl edge and learn from our history, including the Wounded Knee Massacre, in order to provide a proper foundation for building an ever more humane, enlightened, and just society for the future. -

Federal Register/Vol. 83, No. 84/Tuesday, May 1, 2018/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 83, No. 84 / Tuesday, May 1, 2018 / Notices 19099 This notice is published as part of the The NSHS is responsible for notifying This notice is published as part of the National Park Service’s administrative the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma that National Park Service’s administrative responsibilities under NAGPRA, 25 this notice has been published. responsibilities under NAGPRA, 25 U.S.C. 3003(d)(3). The determinations in Dated: April 10, 2018. U.S.C. 3003(d)(3). The determinations in this notice are the sole responsibility of Melanie O’Brien, this notice are the sole responsibility of the museum, institution, or Federal Manager, National NAGPRA Program. the museum, institution, or Federal agency that has control of the Native agency that has control of the Native American human remains. The National [FR Doc. 2018–09174 Filed 4–30–18; 8:45 am] American human remains. The National Park Service is not responsible for the BILLING CODE 4312–52–P Park Service is not responsible for the determinations in this notice. determinations in this notice. Consultation DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Consultation A detailed assessment of the human National Park Service A detailed assessment of the human remains was made by the NSHS remains was made by Discovery Place, professional staff in consultation with [NPS–WASO–NAGPRA–NPS0025396; Inc. professional staff in consultation PPWOCRADN0–PCU00RP14.R50000] representatives of the Pawnee Nation of with representatives of the Catawba Oklahoma. Notice of Inventory Completion: Indian Nation (aka Catawba Tribe of South Carolina). History and Description of the Remains Discovery Place, Inc., Charlotte, NC History and Description of the Remains In 1936, human remains representing, AGENCY: National Park Service, Interior. -

Teacher’S Guide Teacher’S Guide Little Bighorn National Monument

LITTLE BIGHORN NATIONAL MONUMENT TEACHER’S GUIDE TEACHER’S GUIDE LITTLE BIGHORN NATIONAL MONUMENT INTRODUCTION The purpose of this Teacher’s Guide is to provide teachers grades K-12 information and activities concerning Plains Indian Life-ways, the events surrounding the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the Personalities involved and the Impact of the Battle. The information provided can be modified to fit most ages. Unit One: PERSONALITIES Unit Two: PLAINS INDIAN LIFE-WAYS Unit Three: CLASH OF CULTURES Unit Four: THE CAMPAIGN OF 1876 Unit Five: BATTLE OF THE LITTLE BIGHORN Unit Six: IMPACT OF THE BATTLE In 1879 the land where The Battle of the Little Bighorn occurred was designated Custer Battlefield National Cemetery in order to protect the bodies of the men buried on the field of battle. With this designation, the land fell under the control of the United States War Department. It would remain under their control until 1940, when the land was turned over to the National Park Service. Custer Battlefield National Monument was established by Congress in 1946. The name was changed to Little Bighorn National Monument in 1991. This area was once the homeland of the Crow Indians who by the 1870s had been displaced by the Lakota and Cheyenne. The park consists of 765 acres on the east boundary of the Little Bighorn River: the larger north- ern section is known as Custer Battlefield, the smaller Reno-Benteen Battlefield is located on the bluffs over-looking the river five miles to the south. The park lies within the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana, one mile east of I-90. -

Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in English of Native American Origin Found Within

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Indian origin names, were eventually shortened to one-word names, making a few indistinguishable from names of non-Indian origin. Name Categories: Personal and family names of Indian origin contrast markedly with names of non-Indian Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in origin. English of Native American Origin 1. Personal and family names from found within Marquette University Christian saints (e.g. Juan, Johnson): Archival Collections natives- rare; non-natives- common 2. Family names from jobs (e.g. Oftentimes names of Native Miller): natives- rare; non-natives- American origin are based on objects common with descriptive adjectives. The 3. Family names from places (e.g. following list, which is not Rivera): natives- rare; non-native- comprehensive, comprises common approximately 1,000 name variations in 4. Personal and family names from English found within the Marquette achievements, attributes, or incidents University archival collections. The relating to the person or an ancestor names originate from over 50 tribes (e.g. Shot with two arrows): natives- based in 15 states and Canada. Tribal yes; non-natives- yes affiliations and place of residence are 5. Personal and family names from noted. their clan or totem (e.g. White bear): natives- yes; non-natives- no History: In ancient times it was 6. Personal or family names from customary for children to be named at dreams and visions of the person or birth with a name relating to an animal an ancestor (e.g. Black elk): natives- or physical phenominon. Later males in yes; non-natives- no particular received names noting personal achievements, special Tribes/ Ethnic Groups: Names encounters, inspirations from dreams, or are expressed according to the following physical handicaps. -

Wind Through the Buffalo Grass: a Lakota Story Cycle Paul A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 2008 Wind Through the Buffalo Grass: A Lakota Story Cycle Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Wind Through the Buffalo Grass: A Lakota Story Cycle" (2008). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 51. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/51 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Fiction I Historical History I Native Ameri("an Wind Through the Buffalo Grass: A Lakota Story Cycle is a narrative history of the Pine Ridge Lakota tribe of South Dakota, following its history from 1850 to the present day through actual historical events and through the stories of four fictional Lakota children, each related by descent and separated from one another by two generations. The ecology of the Pine Ridge region, especially its mammalian and avian wildlife, is woven into the stories of the children. 111ustrated by the author, the book includes drawings of Pine Ridge wildlife, regional maps, and Native American pictorial art. Appendices include a listing of important Lakota words, and checklists of mammals and breeding birds of the region. Dr. Paul A. Johnsgard is foundation professor of biological sciences emeritus of the University of Nebraska-lincoln. -

II. Sitting Bull's Family / Wives & Children

TThhee PPhhoottooggrraapphhss Based on the Markus Liindner Liistiing iin the North Dakota Hiistory Journall 2005: 2-21. Piictures: Collllectiion Gregor Lutz / Addiitiions and comments iin bllue by Gregor Lutz II. Siittiing Bullll’’s Famiilly / Wiives & chiilldren Photograph / D a t e Description P i c t u r e L i c e n s e e 1885 D.F. Barry Crow Foot, Sitting Bull's Son #1 This is a photograph of Sitting Bull's son, Crow Foot, taken by David F. Barry, circa 1885. Crow Foot surrendered his father's gun to Major Brotherton at Fort Buford in 1881. Sitting Bull maintained that he himself never surrendered. 1885 D.F. Barry Crow Foot, Sitting Bull's Son #2 This is a photograph of Sitting Bull's son, Crow Foot, taken by David F. Barry, circa 1885. 1885 D.F. Barry Standing Holy Sitting Bull's daughter #1 three-quarter length portrait, seated, facing front Library of Congress (LoC) LOT 12887 1885 D.F. Barry Standing Holy Sitting Bull's daughter #2 , three-quarter length portrait, seated, facing front Library of Congress (LoC), LOT 12887 1885 D.F. Barry Standing Holy Sitting Bull's daughter #3 full-length portrait, standing, facing front 1885 D.F. Barry Standing Holy Sitting Bull's daughter #4 full-length portrait, standing, facing front Library of Congress (LoC) LOT 12887 1890 D.F. Barry Sitting Bull's family #1 / 91 Sitting Bull's family in front of the log house at Grand River Left to right: Lodge In Sight, Four Robes, Seen By Her Nation, Standing Holy. -

Lands of the Lakota: Policy, Culture and Land Use on the Pine Ridge

1 Lands of the Lakota: Policy, Culture and Land Use on the Pine Ridge Reservation Joseph Stromberg Senior Honors Thesis Environmental Studies and Anthropology Washington University in St. Louis 2 Abstract Land is invested with tremendous historical and cultural significance for the Oglala Lakota Nation of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Widespread alienation from direct land use among tribal members also makes land a key element in exploring the roots of present-day problems—over two thirds of the reservation’s agricultural income goes to non-Natives, while the majority of households live below the poverty line. In order to understand how current patterns in land use are linked with federal policy and tribal culture, this study draws on three sources: (1) archival research on tribal history, especially in terms of territory loss, political transformation, ethnic division, economic coercion, and land use; (2) an account of contemporary problems on the reservation, with an analysis of current land policy and use pattern; and (3) primary qualitative ethnographic research conducted on the reservation with tribal members. Findings indicate that federal land policies act to effectively block direct land use. Tribal members have responded to policy in ways relative to the expression of cultural values, and the intent of policy has been undermined by a failure to fully understand the cultural context of the reservation. The discussion interprets land use through the themes of policy obstacles, forced incorporation into the world-system, and resistance via cultural sovereignty over land use decisions. Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank the Buder Center for American Indian Studies of the George Warren Brown School of Social Work as well as the Environmental Studies Program, for support in conducting research. -

2018NABI Teams.Pdf

TEAM NAME COACH TRIBE STATE TEAM NAME COACH TRIBE STATE 1 ALASKA (D1) S. Craft Unalakleet, Akiachak, Akiak, Qipnag, Savoonga, Iqurmiut AK 33 THREE NATIONS (D1) G. Tashquinth Tohono O'odham, Navajo, Gila River AZ 2 APACHE OUTKAST (D1) J. Andreas White Mountain Apache AZ 34 TRIBAL BOYZ (D1) A. Strom Colville, Mekah, Nez Perce, Quinault, Umatilla, Yakama WA 3 APACHES (D1) T. Antonio San Carlos Apache AZ 35 U-NATION (D1) J. Miller Omaha Tribe of Nebraska NE 4 AZ WARRIORS (D1) R. Johnston Hopi, Dine, Onk Akimel O'odham, Tohono O'odham AZ 36 YAQUI WARRIORS (D1) N. Gorosave Pascua Yaqui AZ Pima, Tohono O'odham, Navajo, White Mountain Apache, 5 BADNATIONZ (D1) K. Miller Sr. Prairie Band Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Yakama KS 1 21ST NATIVES (D2) R. Lyons AZ Chemehuevi, Hualapai 6 BIRD CITY (D1) M. Barney Navajo AZ 2 AK-CHIN (D2) T. Carlyle Ak-Chin AZ 7 BLUBIRD BALLERZ (D1) B. Whitehorse Navajo UT 3 AZ FUTURE (D2) T. Blackwater Akimel O'odham, Dine, Hopi AZ 8 CHAOS (D1) D. Kohlus Cheyenne River Sioux, Standing Rock Sioux SD 4 AZ OUTLAWS (D2) S. Amador Mohave, Navajo, Chemehuevi, Digueno AZ CHEYENNEARAPAHO 9 R. Island Cheyenne Arapaho Tribes Of Oklahoma OK 5 AZ SPARTANS (D2) G. Pete Navajo AZ (D1) 10 FLIGHT 701 (D1) B. Kroupa Arikara, Hidatsa, Sioux ND 6 DJ RAP SQUAD (D2) R. Paytiamo Navajo NM 11 FMD (D1) Gerald Doka Yavapai, Pima, CRIT AZ 7 FORT YUMA (D2) D. Taylor Quechan CA 12 FORT MOJAVE (D1) J. Rodriguez Jr. Fort Mojave, Chemehuevi, Colorado River Indian Tribes CA 8 GILA RIVER (D2) R. -

Listen to the Grandmothers Video Guide and Resource: Incorporating Tradition Into Contemporary Responses to Violence Against Native Women

Tribal Law and Policy Institute Listen To The Grandmothers Video Guide and Resource: Incorporating Tradition into Contemporary Responses to Violence Against Native Women Listen To The Grandmothers Video Guide and Resource: Incorporating Tradition into Contemporary Responses to Violence Against Native Women Contributors: Bonnie Clairmont, HoChunk Nation April Clairmont, HoChunk Nation Sarah Deer, Mvskoke Beryl Rock, Leech Lake Maureen White Eagle, Métis A Product of the Tribal Law and Policy Institute 8235 Santa Monica Boulevard, Suite 211 West Hollywood, CA 90046 323-650-5468 www.tlpi.org This project was supported by Grant No. 2004-WT-AX-K043 awarded by the Office on Violence Against Women, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Justice, Office on Violence Against Women. Table of Contents Introduction Overview of this Publication 2 Overview of the Listen to the Grandmothers Video 4 How to Use This Guide with the Video 5 Precaution 6 Biographies of Elders in the Listen to the Grandmothers Video 7 Section One: Listen to the Grandmothers Video Transcript 10 What Does It Mean To Be Native?/ What is a Native Woman? 13 Video Part One: Who We Are? 15 Video Part Two: What Has Happened To Us? 18 Stories From Survivors 22 Video Part Three: Looking Forward 26 Section Two: Discussion Questions 31 Section Three: Incorporating Tradition into Contemporary Responses to Violence Against Native -

![HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY COMMEMORATION [S Con. Res. 153]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2188/hundredth-anniversary-commemoration-s-con-res-153-472188.webp)

HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY COMMEMORATION [S Con. Res. 153]

CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—OCT. 25,1990 104 STAT. 5183 violence reveals that violent tendencies may be passed on from one generation to the next; Whereas witnessing an aggressive parent as a role model may communicate to children that violence is an acceptable tool for resolving marital conflict; and Wheregis few States have recognized the interrelated natui-e of child custody and battering and have enacted legislation that allows or requires courts to consider evidence of physical abuse of a spouse in child custody cases: Now, therefore, be it Resolved by the House of Representatives (the Senate concurring), SECTION 1. It is the sense of the Congress that, for purposes of determining child custody, credible evidence of physical abuse of a spouse should create a statutory presumption that it is detrimental to the child to be placed in the custody of the abusive spouse. SEC. 2. This resolution is not intended to encourage States to prohibit supervised visitation. Agreed to October 25, 1990. WOUNDED KNEE CREEK MASSACRE—ONE- oct. 25.1990 HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY COMMEMORATION [s con. Res. 153] Whereas, in order to promote racial harmony and cultural under standing, the Grovernor of the State of South Dakota has declared that 1990 is a Year of Reconciliation between the citizens of the State of South Dakota and the member bands of the Great Sioux Nation; Whereas the Sioux people who are descendants of the victims and survivors of the Wounded Knee Massacre have been striving to reconcile and, in a culturally appropriate manner, to bring to an end -

Massacre on the Plains: a Better Way to Conceptualize

MASSACRE ON THE PLAINS: A BETTER WAY TO CONCEPTUALIZE GENOCIDE ON AMERICAN SOIL by KEATON J KELL A THESIS Presented to the Conflict and Dispute Resolution Program and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science June 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Keaton J Kell Title: Massacre on the Plains: A Better Way to Conceptualize Genocide on American Soil This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in the Conflict and Dispute Resolution Program by: Michael Moffitt Chair Keith Eddins Core Member and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Keaton J Kell iii THESIS ABSTRACT Keaton J Kell Master of Science Conflict and Dispute Resolution Program June 2017 Title: Massacre on the Plains: A Better Way to Conceptualize Genocide on American Soil This thesis examines the massacres of the Plains Indian Wars in the United States (1851-1890) and how they relate to contemporary theories of genocide. By using the Plains Indian Wars as a case study, a critique can be made of theories which inform predictive models and genocide policy. This thesis analyzes newspaper articles, histories, congressional investigations, presidential speeches, and administrative policies surrounding the four primary massacres perpetrated by the United States during this time. An ideology of racial superiority and fears of insecurity, impurity, and insurgency drove the actions of the white settler-colonialists and their military counterparts. -

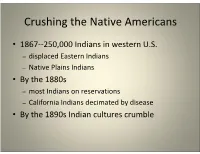

Crushing the Native Americans

Crushing the Native Americans • 1867--250,000 Indians in western U.S. – displaced Eastern Indians – Native Plains Indians • By the 1880s – most Indians on reservations – California Indians decimated by disease • By the 1890s Indian cultures crumble Essential Questions 1) What motivated Americans from the east to move westward? 2) How did American expansion westward affect the American Indians? 3) How was American “identity” forged through westward expansion? Which picture best represents America? What affects our perception of American identity? Life of the Plains Indians: Political Organization • Plains Indians nomadic, hunt buffalo – skilled horsemen – tribes develop warrior class – wars limited to skirmishes, "counting coups" • Tribal bands governed by chief and council • Loose organization confounds federal policy Life of the Plains Indians: Social Organization • Sexual division of labor – men hunt, trade, supervise ceremonial activities, clear ground for planting – women responsible for child rearing, art, camp work, gardening, food preparation • Equal gender status common – kinship often matrilineal – women often manage family property Misconceptions / Truths of Native Americans Misconceptions Truths • Not all speak the same • Most did believe land belonged language or have the same to no one (no private property) traditions • Reservation lands were • Not all live on reservations continually taken away by the • Tribes were not always government unified • Many relied on hunting as a • Most tribes were not hostile way of life (buffalo) • Most tribes put a larger stake on honor rather than wealth Culture of White Settlers • Most do believe in private property • A strong emphasis on material wealth (money) • Few rely on hunting as a way of life; most rely on farming • Many speak the same language and have a similar culture What is important about the culture of white settlers in comparison to the culture of the American Indians? What does it mean to be civilized? “We did not ask you white men to come here.