Code Talkers Hearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 83, No. 84/Tuesday, May 1, 2018/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 83, No. 84 / Tuesday, May 1, 2018 / Notices 19099 This notice is published as part of the The NSHS is responsible for notifying This notice is published as part of the National Park Service’s administrative the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma that National Park Service’s administrative responsibilities under NAGPRA, 25 this notice has been published. responsibilities under NAGPRA, 25 U.S.C. 3003(d)(3). The determinations in Dated: April 10, 2018. U.S.C. 3003(d)(3). The determinations in this notice are the sole responsibility of Melanie O’Brien, this notice are the sole responsibility of the museum, institution, or Federal Manager, National NAGPRA Program. the museum, institution, or Federal agency that has control of the Native agency that has control of the Native American human remains. The National [FR Doc. 2018–09174 Filed 4–30–18; 8:45 am] American human remains. The National Park Service is not responsible for the BILLING CODE 4312–52–P Park Service is not responsible for the determinations in this notice. determinations in this notice. Consultation DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Consultation A detailed assessment of the human National Park Service A detailed assessment of the human remains was made by the NSHS remains was made by Discovery Place, professional staff in consultation with [NPS–WASO–NAGPRA–NPS0025396; Inc. professional staff in consultation PPWOCRADN0–PCU00RP14.R50000] representatives of the Pawnee Nation of with representatives of the Catawba Oklahoma. Notice of Inventory Completion: Indian Nation (aka Catawba Tribe of South Carolina). History and Description of the Remains Discovery Place, Inc., Charlotte, NC History and Description of the Remains In 1936, human remains representing, AGENCY: National Park Service, Interior. -

Lands of the Lakota: Policy, Culture and Land Use on the Pine Ridge

1 Lands of the Lakota: Policy, Culture and Land Use on the Pine Ridge Reservation Joseph Stromberg Senior Honors Thesis Environmental Studies and Anthropology Washington University in St. Louis 2 Abstract Land is invested with tremendous historical and cultural significance for the Oglala Lakota Nation of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Widespread alienation from direct land use among tribal members also makes land a key element in exploring the roots of present-day problems—over two thirds of the reservation’s agricultural income goes to non-Natives, while the majority of households live below the poverty line. In order to understand how current patterns in land use are linked with federal policy and tribal culture, this study draws on three sources: (1) archival research on tribal history, especially in terms of territory loss, political transformation, ethnic division, economic coercion, and land use; (2) an account of contemporary problems on the reservation, with an analysis of current land policy and use pattern; and (3) primary qualitative ethnographic research conducted on the reservation with tribal members. Findings indicate that federal land policies act to effectively block direct land use. Tribal members have responded to policy in ways relative to the expression of cultural values, and the intent of policy has been undermined by a failure to fully understand the cultural context of the reservation. The discussion interprets land use through the themes of policy obstacles, forced incorporation into the world-system, and resistance via cultural sovereignty over land use decisions. Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank the Buder Center for American Indian Studies of the George Warren Brown School of Social Work as well as the Environmental Studies Program, for support in conducting research. -

2018NABI Teams.Pdf

TEAM NAME COACH TRIBE STATE TEAM NAME COACH TRIBE STATE 1 ALASKA (D1) S. Craft Unalakleet, Akiachak, Akiak, Qipnag, Savoonga, Iqurmiut AK 33 THREE NATIONS (D1) G. Tashquinth Tohono O'odham, Navajo, Gila River AZ 2 APACHE OUTKAST (D1) J. Andreas White Mountain Apache AZ 34 TRIBAL BOYZ (D1) A. Strom Colville, Mekah, Nez Perce, Quinault, Umatilla, Yakama WA 3 APACHES (D1) T. Antonio San Carlos Apache AZ 35 U-NATION (D1) J. Miller Omaha Tribe of Nebraska NE 4 AZ WARRIORS (D1) R. Johnston Hopi, Dine, Onk Akimel O'odham, Tohono O'odham AZ 36 YAQUI WARRIORS (D1) N. Gorosave Pascua Yaqui AZ Pima, Tohono O'odham, Navajo, White Mountain Apache, 5 BADNATIONZ (D1) K. Miller Sr. Prairie Band Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Yakama KS 1 21ST NATIVES (D2) R. Lyons AZ Chemehuevi, Hualapai 6 BIRD CITY (D1) M. Barney Navajo AZ 2 AK-CHIN (D2) T. Carlyle Ak-Chin AZ 7 BLUBIRD BALLERZ (D1) B. Whitehorse Navajo UT 3 AZ FUTURE (D2) T. Blackwater Akimel O'odham, Dine, Hopi AZ 8 CHAOS (D1) D. Kohlus Cheyenne River Sioux, Standing Rock Sioux SD 4 AZ OUTLAWS (D2) S. Amador Mohave, Navajo, Chemehuevi, Digueno AZ CHEYENNEARAPAHO 9 R. Island Cheyenne Arapaho Tribes Of Oklahoma OK 5 AZ SPARTANS (D2) G. Pete Navajo AZ (D1) 10 FLIGHT 701 (D1) B. Kroupa Arikara, Hidatsa, Sioux ND 6 DJ RAP SQUAD (D2) R. Paytiamo Navajo NM 11 FMD (D1) Gerald Doka Yavapai, Pima, CRIT AZ 7 FORT YUMA (D2) D. Taylor Quechan CA 12 FORT MOJAVE (D1) J. Rodriguez Jr. Fort Mojave, Chemehuevi, Colorado River Indian Tribes CA 8 GILA RIVER (D2) R. -

Listen to the Grandmothers Video Guide and Resource: Incorporating Tradition Into Contemporary Responses to Violence Against Native Women

Tribal Law and Policy Institute Listen To The Grandmothers Video Guide and Resource: Incorporating Tradition into Contemporary Responses to Violence Against Native Women Listen To The Grandmothers Video Guide and Resource: Incorporating Tradition into Contemporary Responses to Violence Against Native Women Contributors: Bonnie Clairmont, HoChunk Nation April Clairmont, HoChunk Nation Sarah Deer, Mvskoke Beryl Rock, Leech Lake Maureen White Eagle, Métis A Product of the Tribal Law and Policy Institute 8235 Santa Monica Boulevard, Suite 211 West Hollywood, CA 90046 323-650-5468 www.tlpi.org This project was supported by Grant No. 2004-WT-AX-K043 awarded by the Office on Violence Against Women, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Justice, Office on Violence Against Women. Table of Contents Introduction Overview of this Publication 2 Overview of the Listen to the Grandmothers Video 4 How to Use This Guide with the Video 5 Precaution 6 Biographies of Elders in the Listen to the Grandmothers Video 7 Section One: Listen to the Grandmothers Video Transcript 10 What Does It Mean To Be Native?/ What is a Native Woman? 13 Video Part One: Who We Are? 15 Video Part Two: What Has Happened To Us? 18 Stories From Survivors 22 Video Part Three: Looking Forward 26 Section Two: Discussion Questions 31 Section Three: Incorporating Tradition into Contemporary Responses to Violence Against Native -

Sharing Their Stories

OUR VETERANS: SHARING THEIR STORIES A Newspaper in Education Supplement to ES I R O Who are Veterans? R ST R They are men and women who, for many time went on, “veteran” was used to describe I reasons, donned the uniform of our country to any former member of the armed forces or a stand between freedom and tyranny; to take up person who had served in the military. NG THE NG I the sword of justice in defense of the liberties In the mid-19th century, this term was we hold dear; to preserve peace and to calm often shortened to the simple phrase “vets.” The HAR S the winds of war. term came to be used as a way to categorize : : Your mothers and fathers, your and honor those who had served and sacrificed grandparents, your aunts and uncles, your through their roles in the military. neighbors, the shop owners in your community, ETERANS your teachers, your favorite athlete, a Hollywood History of Veterans Day V R star, and your political leaders... each one could World War I, also known as the “Great OU be a veteran. War,” was officially concluded on the 11th But as much as they may differ by gender, hour of the 11th Day of November, at 11 A.M. race, age, national origin, or profession, they in 1918. On November 11th of the following share a common love for our great nation; a year, President Woodrow Wilson declared that love great enough to put their very lives on the day as “Armistice Day” in honor of the peace. -

Some Notes on a Formal Algebraic Structure of Cryptology

mathematics Article Some Notes on a Formal Algebraic Structure of Cryptology Vicente Jara-Vera * and Carmen Sánchez-Ávila Departamento de Matemática Aplicada a las Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones (Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenieros de Telecomunicación), Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Avenida Complutense 30, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34–686–615–535 Abstract: Cryptology, since its advent as an art, art of secret writing, has slowly evolved and changed, above all since the middle of the last century. It has gone on to obtain a more solid rank as an applied mathematical science. We want to propose some annotations in this regard in this paper. To do this, and after reviewing the broad spectrum of methods and systems throughout history, and from the traditional classification, we offer a reordering in a more compact and complete way by placing the cryptographic diversity from the algebraic binary relations. This foundation of cryptological operations from the principles of algebra is enriched by adding what we call pre-cryptological operations which we show as a necessary complement to the entire structure of cryptology. From this framework, we believe that it is improved the diversity of questions related to the meaning, the fundamentals, the statute itself, and the possibilities of cryptological science. Keywords: algebra; cryptography; cryptology MSC: 14G50; 94A60 Citation: Jara-Vera, V.; Sánchez-Ávila, C. Some Notes on a Formal Algebraic Structure of 1. Introduction Cryptology. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2183. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9182183 Cryptology is a science that is usually explained based on its historical development. -

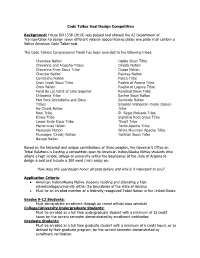

How Does This Seal Design Honor All Code Talkers and Why Is It Important to You?

Code Talker Seal Design Competition Background: House Bill 1338 (2019) was passed and allowed the AZ Department of Transportation to design seven different veteran special license plates one plate shall contain a Native American Code Talker seal. The Code Talkers Congressional Medal has been awarded to the following tribes: Cherokee Nation Oglala Sioux Tribe Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes Oneida Nation Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe Osage Nation Choctaw Nation Pawnee Nation Comanche Nation Ponca Tribe Crow Creek Sioux Tribe Pueblo of Acoma Tribe Crow Nation Pueblo of Laguna Tribe Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Rosebud Sioux Tribe Chippewa Tribe Santee Sioux Nation Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Seminole Nation Tribes Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate (Sioux) Ho-Chunk Nation Tribe Hopi Tribe St. Regis Mohawk Tribe Kiowa Tribe Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Lower Brule Sioux Tribe Tlingit Tribe Menominee Nation Tonto Apache Tribe Meskwaki Nation White Mountain Apache Tribe Muscogee (Creek) Nation Yankton Sioux Tribe Navajo Nation Based on the historical and unique contributions of these peoples, the Governor’s Office on Tribal Relations is hosting a competition open to American Indian/Alaska Native students who attend a high school, college or university within the boundaries of the state of Arizona to design a seal and include a 300 word (min) essay on: How does this seal design honor all code talkers and why is it important to you? Application Criteria: ñ American Indian/Alaska Native students residing and attending a high school/college/university within -

Native Americans and World War II

Reemergence of the “Vanishing Americans” - Native Americans and World War II “War Department officials maintained that if the entire population had enlisted in the same proportion as Indians, the response would have rendered Selective Service unnecessary.” – Lt. Col. Thomas D. Morgan Overview During World War II, all Americans banded together to help defeat the Axis powers. In this lesson, students will learn about the various contributions and sacrifices made by Native Americans during and after World War II. After learning the Native American response to the attack on Pearl Harbor via a PowerPoint centered discussion, students will complete a jigsaw activity where they learn about various aspects of the Native American experience during and after the war. The lesson culminates with students creating a commemorative currency honoring the contributions and sacrifices of Native Americans during and after World War II. Grade 11 NC Essential Standards for American History II • AH2.H.3.2 - Explain how environmental, cultural and economic factors influenced the patterns of migration and settlement within the United States since the end of Reconstruction • AH2.H.3.3 - Explain the roles of various racial and ethnic groups in settlement and expansion since Reconstruction and the consequences for those groups • AH2.H.4.1 - Analyze the political issues and conflicts that impacted the United States since Reconstruction and the compromises that resulted • AH2.H.7.1 - Explain the impact of wars on American politics since Reconstruction • AH2.H.7.3 - Explain the impact of wars on American society and culture since Reconstruction • AH2.H.8.3 - Evaluate the extent to which a variety of groups and individuals have had opportunity to attain their perception of the “American Dream” since Reconstruction Materials • Cracking the Code handout, attached (p. -

Table of Contents

August-September 2015 Edition 4 _____________________________________________________________________________________ We’re excited to share the positive work of tribal nations and communities, Native families and organizations, and the Administration that empowers our youth to thrive. In partnership with the My Brother’s Keeper, Generation Indigenous (“Gen-I”), and First Kids 1st Initiatives, please join our First Kids 1st community and share your stories and best practices that are creating a positive impact for Native youth. To highlight your stories in future newsletters, send your information to [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Youth Highlights II. Upcoming Opportunities & Announcements III. Call for Future Content *************************************************************************************************** 1 th Sault Ste. Marie Celebrates Youth Council’s 20 Anniversary On September 18 and 19, the Sault Ste. Marie Tribal Youth Council (TYC) 20-Year Anniversary Mini Conference & Celebration was held at the Kewadin Casino & Convention Center. It was a huge success with approximately 40 youth attending from across the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians service area. For the past 20 years, tribal youth grades 8-12 have taken on Childhood Obesity, Suicide and Bullying Prevention, Drug Abuse, and Domestic Violence in their communities. The Youth Council has produced PSAs, workshops, and presentations that have been done on local, tribal, state, and national levels and also hold the annual Bike the Sites event, a 47-mile bicycle ride to raise awareness on Childhood Obesity and its effects. TYC alumni provided testimony on their experiences with the youth council and how TYC has helped them in their walk in life. The celebration continued during the evening with approximately 100 community members expressing their support during the potluck feast and drum social held at the Sault Tribe’s Culture Building. -

Honor the Legacy of Navajo Code Talker Kee Etsicitty and Live Courageously

Honor the legacy of Navajo Code Talker Kee Etsicitty and live courageously Navajo Nation President Russell Begaye reads the proclamation he issued that ordered flags across the Navajo Nation to be flown at half-staff in honor of Navajo Code Talker Kee Etsicitty, who passed on July 21. He encouraged the audience to honor Etsicitty’s legacy by living courageously. (Photo by Rick Abasta) GALLUP, N.M.—The bells at home last October. MacDonald, Alfred Neuman and and Navajo Nation Council Sacred Heart Cathedral Church A member of the 3rd Bill Toledo were in attendance. Delegates Seth Damon, Otto tolled on the morning of July 24 Marines, 7th Division, Etsicitty The honor guards from the Tso and Leonard Tsosie. to honor the life of Navajo Code saw combat in the Battles of U.S. Marine Corps and the Ira H. Talker Kee Etsicitty. Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Hayes American Legion Post 84 Faithful Catholic, honorable His body was transported Guam, Saipan and Iwo Jima. from Sacaton, Ariz. were also on American to the church for the memorial hand to honor Etsicitty. According to Etsicitty’s son, services and escorted by the Paying respect to a hero A number of dignitaries Kurtis, his father was a devout members of the Navajo-Hopi Before he was laid to rest, came out to pay their respects, Catholic and said he wanted Honor Riders, the non-profit Etsicitty’s brothers came out including Navajo Nation his funeral services to be held organization that volunteered to honor him. Navajo Code President Russell Begaye, at Cathedral Church. His wish to repair the roof of Etsicitty’s Talkers Thomas H. -

From Scouts to Soldiers: the Evolution of Indian Roles in the U.S

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Summer 2013 From Scouts to Soldiers: The Evolution of Indian Roles in the U.S. Military, 1860-1945 James C. Walker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Walker, James C., "From Scouts to Soldiers: The Evolution of Indian Roles in the U.S. Military, 1860-1945" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 860. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/860 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM SCOUTS TO SOLDIERS: THE EVOLUTION OF INDIAN ROLES IN THE U.S. MILITARY, 1860-1945 by JAMES C. WALKER ABSTRACT The eighty-six years from 1860-1945 was a momentous one in American Indian history. During this period, the United States fully settled the western portion of the continent. As time went on, the United States ceased its wars against Indian tribes and began to deal with them as potential parts of American society. Within the military, this can be seen in the gradual change in Indian roles from mostly ad hoc forces of scouts and home guards to regular soldiers whose recruitment was as much a part of the United States’ war plans as that of any other group. -

Multiculturalism in the Armed Forces in the 20 Century

Multiculturalism in the Armed Forces in the 20th Century Cover: The nine images on the cover, from left to right and top to bottom, are: Japanese-American WACs on their way to Japan on a post-war cultural mission. (U.S. Army photo) African-American aviators in flight suits, Tuskegee Army Air Field, World War II. (Visual Materials from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Records; from the Library of Congress, Reproduction Number LC-USZ62-35362) During the visit of Lieutenant General Robert Gray, the Deputy Commander, USAREUR, Private First Class Donya Irby from the 44th Signal Company, out of Mannheim, Germany, describes how the 173 Van gathers, reads, and transmits signals to its destination as part of Operation Joint Endeavor. (Photo by Sergeant Angel Clemons, 55th Signal Company (comcam), Fort Meade, Maryland 20755. Image # 282 960502-A-1972C-003) U.S. Marine Corps Commandant General Carl E. Mundy poses for a picture with members of the Air Force fire department at Mogadishu Airport, Somalia. General Mundy toured the Restore Hope Theater during the Christmas holiday. (Photo by TSgt Perry Heimer, USAF Combat Camera) President George Bush takes time to shake hands with the troops and pose for pictures after his speech, January 1993, in Somalia. (Photo by TSgt Dave Mcleod, USAF Combat Camera) For his heroic actions in the Long Khanh Province in Vietnam, March 1966, Alfred Rascon (center), a medic, received the Medal of Honor three decades later. (Photo courtesy of the Army News Service) Navajo code talkers on Bouganville. (U.S. Marine Corps archive photo) On December 19, 1993, General John M.