Native Americans and World War II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alshire Records Discography

Alshire Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Alshire International Records Discography Alshire was located at P.O. Box 7107, Burbank, CA 91505 (Street address: 2818 West Pico Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90006). Founded by Al Sherman in 1964, who bought the Somerset catalog from Dick L. Miller. Arlen, Grit and Oscar were subsidiaries. Alshire was a grocery store rack budget label whose main staple was the “101 Strings Orchestra,” which was several different orchestras over the years, more of a franchise than a single organization. Alshire M/S 3000 Series: M/S 3001 –“Oh Yeah!” A Polka Party – Coal Diggers with Happy Tony [1967] Reissue of Somerset SF 30100. Oh Yeah!/Don't Throw Beer Bottles At The Band/Yak To Na Wojence (Fortunes Of War)/Piwo Polka (Beer Polka)/Wanda And Stash/Moja Marish (My Mary)/Zosia (Sophie)/Ragman Polka/From Ungvara/Disc Jocky Polka/Nie Puki Jashiu (Don't Knock Johnny) Alshire M/ST 5000 Series M/ST 5000 - Stephen Foster - 101 Strings [1964] Beautiful Dreamer/Camptown Races/Jeannie With The Light Brown Hair/Oh Susanna/Old Folks At Home/Steamboat 'Round The Bend/My Old Kentucky Home/Ring Ring De Bango/Come, Where My Love Lies Dreaming/Tribute To Foster Medley/Old Black Joe M/ST 5001 - Victor Herbert - 101 Strings [1964] Ah! Sweet Mystery Of Life/Kiss Me Again/March Of The Toys, Toyland/Indian Summer/Gypsy Love Song/Red Mill Overture/Because You're You/Moonbeams/Every Day Is Ladies' Day To Me/In Old New York/Isle Of Our Dreams M/S 5002 - John Philip Sousa, George M. -

From Flags of Our Fathers to Letters from Iwo Jima: Clint Eastwood's Balancing of Japanese and American Perspectives

Volume 4 | Issue 12 | Article ID 2290 | Dec 02, 2006 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus From Flags of Our Fathers to Letters From Iwo Jima: Clint Eastwood's Balancing of Japanese and American Perspectives Aaron Gerow From Flags of Our Fathers to Letters From Iwo Jima: Clint Eastwood’s Balancing of Japanese and American Perspectives By Aaron Gerow History, like the cinema, can often be a matter of perspective. That’s why Clint Eastwood’s decision to narrate the Battle of Iwo Jima from both the American and the Japanese point of view is not really new; it had been done before in Tora Tora Tora (1970), for instance. But by dividing these perspectives in different films directed at Japanese and international audiences, Eastwood makes history not merely an issue of which side you are on, but of how to look at history itself. Flags of Our Fathers, the American version, is less about the battle than the memory of war, focusing in particular on how nations compulsively create heroes when they need them (like with the soldiers who raised the flag on Iwo Jima) and forget them later when they don’t. Instead of giving the national narrative of bravery in capturing Iwo Jima, the film shows how such stories are manufactured by media and governments to further the aims of the country, whatever may be the truth or the 1 4 | 12 | 0 APJ | JF feelings of the individual soldiers. Against the And some of the figures are fascinating. constructed nature of public heroism, Eastwood Kuribayashi (Watanabe Ken) had studied in the poses the private real bonds between men; United States, wrote loving letters to his son against public memory he focuses on personal with comic illustrations, and protected his men trauma. -

Johnny Cash: the Man, His World, His Music,” Tuesday, Aug

For Immediate Release Contacts: P.O.V. Communications: 212-989-7425. Emergency contact: 646-729-4748 Cynthia López, [email protected], Cathy Fisher, [email protected] P.O.V. online pressroom: www.pbs.org/pov/pressroom P.O.V. Revives Classic 1969 Portrait of “Johnny Cash: The Man, His World, His Music,” Tuesday, Aug. 5 on PBS Film Captures Cash on the Road, on Stage and Behind the Scenes Fresh on the Heels of His Breakthrough “Folsom Prison” Album; June Carter Cash, Bob Dylan, Carl Perkins Featured “…a rousing masterpiece.” – Rolling Stone Magazine When the Man in Black died in September 2003, he closed an original and captivating chapter in the great American songbook. Even as death approached, Johnny Cash displayed the hardscrabble grit, authentic individualism and knack for doing the unexpected that had made him an American icon — his powerful video cover of Trent Reznor’s “Hurt,” showing him visibly ailing but resolute, was nominated for six MTV Video Music Awards that year. It had been a long, maybe improbable, certainly American journey for a sharecropper’s son from Kingsland, Ark., and it had more ups and downs and surprising turns than a country road. In 1968, Robert Elfstrom (who went on to an award-winning career as a cinematographer and director) had the insight to make a documentary on Cash — and the luck to strike up a warm and candid rapport with the temperamental singer. By then, Cash, who had begun his career in the late ‘50s, had won over country music audiences with his uniquely intense "underdog" ballads, and was experiencing the first of several crossover successes with Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison. -

C H a P T E R 25 World War II

NASH.7654.CP25p826-861.vpdf 9/23/05 3:35 PM Page 826 CHAPTER 25 World War II This World War II poster depicts the many nations united in the fight against the Axis powers. In reality there were often disagreements. Notice that to the right, the American sailor is marching next to Chinese and Soviet soldiers. Within a few years after victory, they would be enemies. (University of Georgia Libraries, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library) American Stories A Native American Boy Plays at War N. Scott Momaday, a Kiowa Indian born in Lawton, Oklahoma, in 1934, grew up on Navajo,Apache, and Pueblo reservations. He was only 11 years old when World War II ended, yet the war had changed his life. Shortly after the United States entered the war, Momaday’s parents moved to New Mexico, where his father got a job with an oil company and his mother worked in the civilian personnel office at an army air force 826 NASH.7654.CP25p826-861.vpdf 9/23/05 3:35 PM Page 827 CHAPTER OUTLINE base. Like many couples, they had struggled through the hard times of the Depression. The Twisting Road to War The war meant jobs. Foreign Policy in a Global Age Momaday’s best friend was Billy Don Johnson, a “reddish, robust boy of great good Europe on the Brink of War humor and intense loyalty.” Together they played war, digging trenches and dragging Ethiopia and Spain themselves through imaginary minefields. They hurled grenades and fired endless War in Europe rounds from their imaginary machine guns, pausing only to drink Kool-Aid from their The Election of 1940 canteens.At school, they were taught history and math and also how to hate the enemy Lend-Lease and be proud of America. -

Sharing Their Stories

OUR VETERANS: SHARING THEIR STORIES A Newspaper in Education Supplement to ES I R O Who are Veterans? R ST R They are men and women who, for many time went on, “veteran” was used to describe I reasons, donned the uniform of our country to any former member of the armed forces or a stand between freedom and tyranny; to take up person who had served in the military. NG THE NG I the sword of justice in defense of the liberties In the mid-19th century, this term was we hold dear; to preserve peace and to calm often shortened to the simple phrase “vets.” The HAR S the winds of war. term came to be used as a way to categorize : : Your mothers and fathers, your and honor those who had served and sacrificed grandparents, your aunts and uncles, your through their roles in the military. neighbors, the shop owners in your community, ETERANS your teachers, your favorite athlete, a Hollywood History of Veterans Day V R star, and your political leaders... each one could World War I, also known as the “Great OU be a veteran. War,” was officially concluded on the 11th But as much as they may differ by gender, hour of the 11th Day of November, at 11 A.M. race, age, national origin, or profession, they in 1918. On November 11th of the following share a common love for our great nation; a year, President Woodrow Wilson declared that love great enough to put their very lives on the day as “Armistice Day” in honor of the peace. -

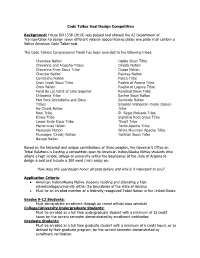

How Does This Seal Design Honor All Code Talkers and Why Is It Important to You?

Code Talker Seal Design Competition Background: House Bill 1338 (2019) was passed and allowed the AZ Department of Transportation to design seven different veteran special license plates one plate shall contain a Native American Code Talker seal. The Code Talkers Congressional Medal has been awarded to the following tribes: Cherokee Nation Oglala Sioux Tribe Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes Oneida Nation Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe Osage Nation Choctaw Nation Pawnee Nation Comanche Nation Ponca Tribe Crow Creek Sioux Tribe Pueblo of Acoma Tribe Crow Nation Pueblo of Laguna Tribe Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Rosebud Sioux Tribe Chippewa Tribe Santee Sioux Nation Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Seminole Nation Tribes Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate (Sioux) Ho-Chunk Nation Tribe Hopi Tribe St. Regis Mohawk Tribe Kiowa Tribe Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Lower Brule Sioux Tribe Tlingit Tribe Menominee Nation Tonto Apache Tribe Meskwaki Nation White Mountain Apache Tribe Muscogee (Creek) Nation Yankton Sioux Tribe Navajo Nation Based on the historical and unique contributions of these peoples, the Governor’s Office on Tribal Relations is hosting a competition open to American Indian/Alaska Native students who attend a high school, college or university within the boundaries of the state of Arizona to design a seal and include a 300 word (min) essay on: How does this seal design honor all code talkers and why is it important to you? Application Criteria: ñ American Indian/Alaska Native students residing and attending a high school/college/university within -

Arizona SIG Application (PDF)

School Improvement Grants Application Section 1003(g) of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act Fiscal Year 2010 CFDA Number: 84.377A State Name:Arizona U.S. Department of Education Washington, D.C. 20202 OMB Number: 1810-0682 Expiration Date: September 30, 2013 Paperwork Burden Statement According to the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995, no persons are required to respond to a collection of information unless such collection displays a valid OMB control number. The valid OMB control number for this information collection is 1810-0682. The time required to complete this information collection is estimated to average 100 hours per response, including the time to review instructions, search existing data resources, gather the data needed, and complete and review the information collection. If you have any comments concerning the accuracy of the time estimate or suggestions for improving this form, please write to: U.S. Department of Education, Washington, D.C. 20202-4537. i SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT GRANTS Purpose of the Program School Improvement Grants (SIG), authorized under section 1003(g) of Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (Title I or ESEA), are grants to State educational agencies (SEAs) that SEAs use to make competitive subgrants to local educational agencies (LEAs) that demonstrate the greatest need for the funds and the strongest commitment to use the funds to provide adequate resources in order to raise substantially the achievement of students in their lowest-performing schools. Under the final requirements published in the Federal Register on October 28, 2010 (http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2010-10-28/pdf/2010- 27313.pdf), school improvement funds are to be focused on each State’s ―Tier I‖ and ―Tier II‖ schools. -

Code Talkers Hearing

S. HRG. 108–693 CODE TALKERS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON CONTRIBUTIONS OF NATIVE AMERICAN CODE TALKERS IN AMERICAN MILITARY HISTORY SEPTEMBER 22, 2004 WASHINGTON, DC ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 96–125 PDF WASHINGTON : 2004 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado, Chairman DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii, Vice Chairman JOHN McCAIN, Arizona, KENT CONRAD, North Dakota PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico HARRY REID, Nevada CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota JAMES M. INHOFE, Oklahoma TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota GORDON SMITH, Oregon MARIA CANTWELL, Washington LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska PAUL MOOREHEAD, Majority Staff Director/Chief Counsel PATRICIA M. ZELL, Minority Staff Director/Chief Counsel (II) C O N T E N T S Page Statements: Brown, John S., Chief of Military History and Commander, U.S. Army Center of Military History ............................................................................ 5 Campbell, Hon. Ben Nighthorse, U.S. Senator from Colorado, chairman, Committee on Indian Affairs ....................................................................... 1 Inhofe, Hon. James M., U.S. Senator from Oklahoma .................................. 2 Johnson, Hon. -

Arizona Water Settlements Act

S. HRG. 108–216 ARIZONA WATER SETTLEMENTS ACT JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON WATER AND POWER OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES AND THE COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON S. 437 TO PROVIDE FOR ADJUSTMENTS TO THE CENTRAL ARIZONA PROJECT IN ARIZONA, TO AUTHORIZE THE GILA RIVER INDIAN COMMUNITY WATER RIGHTS SETTLEMENT, TO AUTHORIZE AND AMEND THE SOUTHERN ARIZONA WATER RIGHTS SETTLEMENT ACT OF 1982, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES SEPTEMBER 30, 2003 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources and the Committee on Indian Affairs U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 90–840 PDF WASHINGTON : 2003 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 11:09 Dec 16, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 J:\DOCS\90-840 SENERGY3 PsN: SENE3 COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico, Chairman DON NICKLES, Oklahoma JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming BOB GRAHAM, Florida LAMAR ALEXANDER, Tennessee RON WYDEN, Oregon LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota JAMES M. TALENT, Missouri MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana CONRAD BURNS, Montana EVAN BAYH, Indiana GORDON SMITH, Oregon DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California JIM BUNNING, Kentucky CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York JON KYL, Arizona MARIA CANTWELL, Washington ALEX FLINT, Staff Director JUDITH K. -

Teacher's Guide for Quiet Hero the Ira Hayes Story

Lee & Low Books Quiet Hero Teacher’s Guide p.1 Classroom Guide for QUIET HERO: THE IRA HAYES STORY by S.D. Nelson Reading Level *Reading Level: Grades 4 UP Interest Level: Grades 2-8 Guided Reading Level: P Lexile™ Measure: 930 *Reading level based on the Spache Readability Formula Themes Heroism, Patriotism, Personal Courage, Loyalty, Honor, World War II, Native American History National Standards SOCIAL STUDIES: Culture; Individual Development and Identity; Individuals, Groups, and Institutions LANGUAGE ARTS: Understanding the Human Experience; Multicultural Understanding Born on the Gila River Indian Reservation in Arizona, Ira Hayes was a bashful boy who never wanted to be the center of attention. At the government-run boarding school he attended, he often felt lonely and out of place. When the United States entered World War II, Hayes joined the Marines to serve his country. He thrived at boot camp and finally felt as if he belonged. Hayes fought honorably on the Pacific front and in 1945 was sent with his battalion to Iwo Jima, a tiny island south of Japan. There he took part in the ferocious fighting to secure the island. On February 23, 1945, Hayes was one of six men who raised the American flag on the summit of Mount Suribachi at the far end of the island. A photographer for the Associated Press, Joe Rosenthal, caught the flag- raising with his camera. Rosenthal’s photo became an iconic image of American courage and is one of the best-known war pictures ever taken. The photograph also catapulted Ira Hayes into the role of national hero, a position he felt he hadn’t earned. -

December 2, 2016 Vol

eg a eve tict the Ga Re Ia t akwate ahe eh G ata ah ate aa y DECEMBER 2, 2016 WWW.GRICNEWS.ORG VOL. 19, NO. 23 GRIC, 7 Arizona Tribes Sign Gaming Compact Amendment Change Service Requested AZ 85147 Sacaton, Box 459 P.O. News Gila River Indian Agreement Gives Tribes Who Agree To Keep Metro Phoenix Free Of New Casinos Potential to Grow Gaming Operations Christopher Lomahquahu Gila River Indian News Together with Gov. Doug Ducey, the Gila River Indian Community and seven other Ari- zona tribes signed amendments to the 2002 tribal gaming compacts and an accompanying agreement designed to open up new compact PRESORTED Permit No. 25 No. Permit STANDARD U.S. Postage U.S. talks on Nov. 21. AZ Sacaton, The updated agreement be- PAID tween the tribes and the State could give tribes who have kept the promise not to open new ca- sinos in metropolitan Phoenix the ability to grow their tribal gaming operations. Community tribal council IN the GRIN representatives accompanied Gov. Stephen Roe Lewis, who signed the amendments. Internment camp According to a GRIC press release Gov. Lewis said, “This Christopher Lomahquahu/GRIN vandalized is a significant step forward for Gov. Stephen Roe Lewis, left, along with seven other tribal leaders, during the compact amendment Page 3 these eight tribes, who have stood signing ceremony at the Arizona State Capitol in Phoenix, Ariz., on Nov. 21. by the promise we all made in How much is an 2002 not to open any additional “Because [these] tribes have Gov. Ducey and tribal leaders cant economic development and casinos in the metropolitan Phoe- been trusted allies with the state, talked about the positive impacts opportunities much to the benefit acre foot of water? we will now have the opportunity of tribal gaming on the state and of Arizona healthcare and Arizo- nix area.” Page 4 He said the signing of the to see a substantial return for hav- tribal communities that are fund- na education.” amendments is about acting in ing kept our promise to Arizona’s ed by revenue from casinos. -

Honor the Legacy of Navajo Code Talker Kee Etsicitty and Live Courageously

Honor the legacy of Navajo Code Talker Kee Etsicitty and live courageously Navajo Nation President Russell Begaye reads the proclamation he issued that ordered flags across the Navajo Nation to be flown at half-staff in honor of Navajo Code Talker Kee Etsicitty, who passed on July 21. He encouraged the audience to honor Etsicitty’s legacy by living courageously. (Photo by Rick Abasta) GALLUP, N.M.—The bells at home last October. MacDonald, Alfred Neuman and and Navajo Nation Council Sacred Heart Cathedral Church A member of the 3rd Bill Toledo were in attendance. Delegates Seth Damon, Otto tolled on the morning of July 24 Marines, 7th Division, Etsicitty The honor guards from the Tso and Leonard Tsosie. to honor the life of Navajo Code saw combat in the Battles of U.S. Marine Corps and the Ira H. Talker Kee Etsicitty. Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Hayes American Legion Post 84 Faithful Catholic, honorable His body was transported Guam, Saipan and Iwo Jima. from Sacaton, Ariz. were also on American to the church for the memorial hand to honor Etsicitty. According to Etsicitty’s son, services and escorted by the Paying respect to a hero A number of dignitaries Kurtis, his father was a devout members of the Navajo-Hopi Before he was laid to rest, came out to pay their respects, Catholic and said he wanted Honor Riders, the non-profit Etsicitty’s brothers came out including Navajo Nation his funeral services to be held organization that volunteered to honor him. Navajo Code President Russell Begaye, at Cathedral Church. His wish to repair the roof of Etsicitty’s Talkers Thomas H.