From Scouts to Soldiers: the Evolution of Indian Roles in the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part I: the Spanish-American War Ameican Continent

Part I: The Spanish-American War rf he ro,d $ 1j.h would FventuaJly lead to Lhe lapa- Amedcans. extendiry U.S. conftol over the lush Gland I nese attack on fearl H"rbor ln l94l and ninety miles from the tip of Florida seemed only logi- Amedca's involvement in Vieham began in the hot cal. Cuba was often depicled as a choice piece of ituit sugar cane fields of Cuba over a century ago. which would naturally Iall into the yard oI iis pow- Cuba, the lar8esi island in the Caibbearr held ertul neighbor when tully iipe. special significance for policymakers in both Spain and the United States at the end of the 19ih c€ntury. lf is aut dcshnv lo hauc Cuba and it is to folly I For Spain, Cuba n'as the last majof remnant of whai debale lhe question. ll naluftll! bplong< la thp I had once been a huge empire in the New World. Ameican continent. I N€arly all of Spain s possessions in ihe Westem Hend- Douglas, 1860 presidential candidatu'l -StEhen sphere had been lost in the early 1800s. and Spain itself had sunk to the level of a third-raie European power. Nonetheless, the government in Maddd refused to RevoLutror'r rt{ Cual consider granting independence io Cuba - "the Pear] of the Antilles" - or seliing the island to anoiher In 186& a revolt against Spanish rule broke out in Cuba. Many of ihe leading rebels hoped to eventu' At the time, the country with ihe geatest inter- ally join the United Staies after breaking {ree fiom est in a.quirin8 Cuba wac LhF United Sidte-. -

William Jennings Bryan and His Opposition to American Imperialism in the Commoner

The Uncommon Commoner: William Jennings Bryan and his Opposition to American Imperialism in The Commoner by Dante Joseph Basista Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2019 The Uncommon Commoner: William Jennings Bryan and his Opposition to American Imperialism in The Commoner Dante Joseph Basista I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Dante Basista, Student Date Approvals: Dr. David Simonelli, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Martha Pallante, Committee Member Date Dr. Donna DeBlasio, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT This is a study of the correspondence and published writings of three-time Democratic Presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan in relation to his role in the anti-imperialist movement that opposed the US acquisition of the Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico following the Spanish-American War. Historians have disagreed over whether Bryan was genuine in his opposition to an American empire in the 1900 presidential election and have overlooked the period following the election in which Bryan’s editorials opposing imperialism were a major part of his weekly newspaper, The Commoner. The argument is made that Bryan was authentic in his opposition to imperialism in the 1900 presidential election, as proven by his attention to the issue in the two years following his election loss. -

Darcy Sorensen

National winner Nt Young Historian Darcy Sorensen Casuarina senior college To what extent was Marquis de Lafayette, prior to 1834, responsible for social change? P a g e | 1 NATIONAL HISTORY CHALLENGE: MAKING A BETTER WORLD To what extent was Marquis de Lafayette, prior to 1834, responsible for positive social change? DARCY SORENSEN CASUARINA SENIOR COLLEGE Darwin, Northern Territory Word count: 1956 words P a g e | 2 Prior to 1834, Marquis de Lafayette was prominently responsible for positive social change. Given the title “hero of two worlds”1 Lafayette disobeyed the orders of Louis XXVI to fight for freedom in the American Revolution. Furthermore, influenced by the ideals of the American Revolution Lafayette worked to abolish slavery in America. In addition, with his position in the French National Assembly Lafayette helped install positive social change. Lafayette’s influence on positive social reforms was also present when he incessantly campaigned for the right to religious freedom in France. However, while his influence was predominantly positive, Lafayette’s influence on society plummeted with his involvement in the Champ De Mars Massacre. On “June 13th, 1777”2 Marquis de Lafayette disobeyed the French government and journeyed to America to fight in the American Revolution. By defying the orders of King Louis XVI Lafayette became one of the key individuals who ensured the freedom of America from Britain’s rule. A significant instance of Lafayette’s military prowess in the fight for freedom was at the Battle of the Brandywine beginning “September 11th, 1777”3. Despite being Lafayette’s first battle, and suffering a bullet wound to the leg, the Frenchman “gallantly fought on and rallied the troops, facilitating an orderly retreat”4 of the troops that saved many lives. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Honor among Thieves: Horse Stealing, State-Building, and Culture in Lincoln County, Nebraska, 1860 - 1890 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1h33n2hw Author Luckett, Matthew S Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Honor among Thieves: Horse Stealing, State-Building, and Culture in Lincoln County, Nebraska, 1860 – 1890 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Matthew S Luckett 2014 © Copyright by Matthew S Luckett 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Honor among Thieves: Horse Stealing, State-Building, and Culture in Lincoln County, Nebraska, 1860 – 1890 by Matthew S Luckett Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Stephen A. Aron, Chair This dissertation explores the social, cultural, and economic history of horse stealing among both American Indians and Euro Americans in Lincoln County, Nebraska from 1860 to 1890. It shows how American Indians and Euro-Americans stole from one another during the Plains Indian Wars and explains how a culture of theft prevailed throughout the region until the late-1870s. But as homesteaders flooded into Lincoln County during the 1870s and 1880s, they demanded that the state help protect their private property. These demands encouraged state building efforts in the region, which in turn drove horse stealing – and the thieves themselves – underground. However, when newspapers and local leaders questioned the efficacy of these efforts, citizens took extralegal steps to secure private property and augment, or subvert, the law. -

Child Development Center Opens in Durant

A Choctaw The 5 Tribes 6th veteran value Storytelling Annual tells his of hard Conference Pow Wow story work to be held Page 5 Page 7 Page 10 Page 14 BISKINIK CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED PRESORT STD P.O. Box 1210 AUTO Durant OK 74702 U.S. POSTAGE PAID CHOCTAW NATION BISKINIKThe Official Publication of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma November 2010 Issue Serving 203,830 Choctaws Worldwide Choctaws ... growing with pride, hope and success Tribal Council holds October Child Development Center opens in Durant regular session By LARISSA COPELAND The Choctaw Nation Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma Tribal Council met on A ribboncutting was held Oct. 9 in regular session at the new state-of-the-art at Tushka Homma. Trib- Choctaw Nation Child De- al Council Speaker Del- velopment Center in Durant ton Cox called the meet- on Oct. 19, marking the end ing to order, welcomed of five years of preparation, guests and then asked for construction and hard work, committee reports. After and the beginning of learn- committee reports were ing, laughter and growth at given the Tribal Council the center. addressed new business. On hand for the cer- •Approval of sev- emony was Choctaw Chief eral budgets including: Gregory E. Pyle, Assistant Upward Bound Math/ Chief Gary Batton, Chicka- Science Program FY saw Nation Governor Bill 2011, DHHS Center for Anoatubby, U.S. Congress- Medicare and Medicaid man Dan Boren, Senator Services Center for Med- Jay Paul Gumm, Durant icaid and State Opera- Mayor Jerry Tomlinson, tions Children’s Health Chief Gregory E. Pyle, Assistant Chief Gary Batton, and a host of tribal, state and local dignitaries cut the rib- Durant City Manager James Insurance Program bon at the new Child Development Center in Durant. -

Becoming Valley Forge Regional Fiction Award Release

PO Box 207, Paoli, Pennsylvania 19301 [email protected] 610-296-4966 (p) 610-644-4436 (f) www.TheElevatorGroup.com NEWS RELEASE – FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE – 4/25/16 Contact: Sheilah Vance 610-296-4966 Email: [email protected] Sheilah Vance’s new novel, Becoming Valley Forge, wins Regional Fiction category in the Next Generation Indie Book Awards PAOLI, PA—Award-winning author Sheilah Vance’s new novel, Becoming Valley Forge, (January 2016, 564 pp., $17.95, The Elevator Group, ISBN 978-0-9824945-9-2) won the category of Regional Fiction in the Next Generation Indie Book Awards, the largest non-profit awards program open to independent publishers and authors worldwide. Vance will receive a gold medal and cash award at a reception held during Book Expo America on May 11, 2016 in Chicago. “I’m very pleased that Becoming Valley Forge received this honor,” said Vance. “My novel certainly tells the story of what happened when the war came to the backyards of ordinary people who lived in the Philadelphia region during the Philadelphia Campaign of the Revolutionary War.” The Midwest Book Review, in April 2016, said of Becoming Valley Forge, “Although a work of fiction, author Sheilah Vance has included a great deal of historically factual background details in her stirring saga of a novel. Impressively well written from beginning to end, "Becoming Valley Forge" is highly recommended for both community and academic library Historical Fiction collections.” Becoming Valley Forge dramatically answers the question of what happens when the war comes to your backyard. In this case the war is the Revolutionary War, and the backyards are of those people in the Valley Forge area whose lives were disrupted during the Philadelphia Campaign, a series of battles and maneuvers from the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777 to the encampment at Valley Forge from December 1777 to June 1778. -

The Impact of Unions in the 1890S: the Case of the New Hampshire Shoe Industry

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #17-89 March 1989 The Impact of Unions In The 1890s: The Case of The New Hampshire Shoe Industry Steven Maddox and Barry Eichengreen Cite as: Steven Maddox and Barry Eichengreen. (1989). “The Impact of Unions In The 1890s: The Case of The New Hampshire Shoe Industry.” IRLE Working Paper No. 17-89. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/17-89.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers Institute for Research on Labor and Employment UC Berkeley Title: The Impact of Unions in the 1890's: The Case of the New Hampshire Shoe Industry Author: Maddox, Steven, University of Virginia Eichengreen, Barry, University of California, Berkeley Publication Date: 03-01-1989 Series: Working Paper Series Publication Info: Working Paper Series, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, UC Berkeley Permalink: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/5mh1p30m Keywords: Maddox, Eichengreen, New Hampshire, shoe industry, unions Copyright Information: All rights reserved unless otherwise indicated. Contact the author or original publisher for any necessary permissions. eScholarship is not the copyright owner for deposited works. Learn more at http://www.escholarship.org/help_copyright.html#reuse eScholarship provides open access, scholarly publishing services to the University of California and delivers a dynamic research platform to scholars worldwide. The Impact of Unions in the 1890s: The Case of the New Hampshire Shoe Industry Steven Maddox University of Virginia Barry Eichengreen University of California, Berkeley We are grateful to Mary Blewett for advice and assistance in categorizing shoe industry occupations, and to Professor Blewett, Susan Carter and Stanley Engerman for helpful comments. Since John Commons's History of Labor in America, the overwhelming majority of histories of the American labor movement have depicted 19th century unionism as little more than the ideological seed from which modern American unionism grew. -

Cradle of Texas Chapter #33 Sons of the American Revolution

Sons of the American Revolution Cradle of Texas Crier Cradle of Texas Chapter # 33 www.cradletxsar.org Volume 20, Number 10 May 2018 Michael J. Bailey, Editor . May Next Meeting family; Patty Jensen – DAR; Mark & 11:30 a.m. Brenda Hansen; Bud & Mary May 12, 2018 Northington. Fat Grass Restaurant RECOGNITION OF COMPATRIOTS: 1717 7th Street President Beall asked that we keep Arthur Evans and Ted Bates and Mary Bay City, Texas Ruth Rhodenbaugh in our thoughts and prayers. Program: GET TO KNOW YOUR COMPATRIOTS: Thomas I. Jackson Kinnan Stockton gave a brief history of Texas SAR, State Society President his youth and education in Louise and El Campo, returning after college to join MEETING MINUTES the 1st State Bank and later becoming its Sons of the American current president. He followed with Revolution information about his Patriot, John Stockton, who’s uncle Richard Stockton Cradle of Texas Chapter #33 April 14, 2018 was the only signer of the Declaration of Independence who was captured by the The Sons of the American Revolution British, imprisoned, starved and locked st met April 14, 2018 at 1 State Bank, 206 in irons with little protection from the North Street Louise, Texas. SAR freezing weather. He was pardoned by President Ray Beall called the meeting General Howe after General to order at 11:36 a.m. Chaplain Michael Washington protested he “shocking and Bailey gave the invocation and blessing inhuman treatment”. for the meal, and Secretary Winston Avera led the Chapter in the U.S., Texas MINUTES: and SAR pledges. President Beall called for approval of the February minutes. -

Montana Governor Response

OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR STATE OF MONTANA STEVE BULLOCK MIKE COONEY GOVERNOR LT. GOVERNOR August 28, 2020 The Honorable David Bernhardt Secretary of the Interior U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C St. NW Washington, DC 20240 Dear Secretary Bernhardt: Thank you for your letter regarding the proposed National Garden of American Heroes and the request for potential locations, statues, and recommendations of Montana heroes. Montana has an abundance of public lands and spaces as well as heroes that we cherish and are worth considering as your Task Force contemplates the National Garden. I am aware that Yellowstone County, our state's largest county by population has put forward a thoughtful proposal that I hope will be given your full consideration. I would suggest that as you further develop selection criteria for the location and the heroes to include in the garden that you undertake a more robust consultation effort with county, tribal and local governments, as I am sure that other localities in the state may have an interest but may not be aware of the opp01iunity. Should Montana be chosen for the National Garden, my administration would be happy to assist with identifying further potential locations within the state, connecting you with local officials, as well as identifying any existing statues for the garden. The Big Sky State has a long, proud history dating well before statehood of men and women who have contributed greatly to both our state and nation. To provide a comprehensive list of Montanans deserving recognition would be nearly impossible. However, I have consulted with the Montana Historical Society, and they have recommended a short list, attached, of Montana heroes who would represent our state and its values well. -

AL SIEBER, FAMOUS SCOUT of the SOUTHWEST (By DAN R

Al Sieber, Famous Scout Item Type text; Article Authors Williamson, Dan R. Publisher Arizona State Historian (Phoenix, AZ) Journal Arizona Historical Review Rights This content is in the public domain. Download date 29/09/2021 08:22:29 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/623491 60 ARIZONA HISTORICAL REVIEW AL SIEBER, FAMOUS SCOUT OF THE SOUTHWEST (By DAN R. WILLIAMSON) Albert Sieber was born in the Grand Dutchy of Baden, Ger- many, February 29, '1844, and died near Roosevelt, Arizona, February 19, 1907. Came to America with his parents as a small boy, settling for a time in Pennsylvania, then moved to Minnesota. Early in 1862 Sieber enlisted in Company B, First Minne- sota Volunteer Infantry, serving through the strenuous Penin- sula campaign of the Army of the Potomac as a corporal and a sharp-shooter. On July 2, 1863, on Gettysburg Battlefield, he was dangerously wounded in the head by a piece of shell, and while lying helpless and unattended on the field of battle a bul- let entered his right ankle and followed up the leg, coming out at the knee. He lay in the hospital until December, 1863, when he was transferred to the First Regiment of Veteran Reserves as a corporal, under Captain Morrison, and his regiment was ac- credited to the State of Massachusetts. When Sieber fell wound- ed on the field of Gettysburg, General Hancock, who was near him, was wounded at the same time. For Sieber 's service with this regiment the State of Massachusetts paid him the sum of $300 bounty. -

Sharing Their Stories

OUR VETERANS: SHARING THEIR STORIES A Newspaper in Education Supplement to ES I R O Who are Veterans? R ST R They are men and women who, for many time went on, “veteran” was used to describe I reasons, donned the uniform of our country to any former member of the armed forces or a stand between freedom and tyranny; to take up person who had served in the military. NG THE NG I the sword of justice in defense of the liberties In the mid-19th century, this term was we hold dear; to preserve peace and to calm often shortened to the simple phrase “vets.” The HAR S the winds of war. term came to be used as a way to categorize : : Your mothers and fathers, your and honor those who had served and sacrificed grandparents, your aunts and uncles, your through their roles in the military. neighbors, the shop owners in your community, ETERANS your teachers, your favorite athlete, a Hollywood History of Veterans Day V R star, and your political leaders... each one could World War I, also known as the “Great OU be a veteran. War,” was officially concluded on the 11th But as much as they may differ by gender, hour of the 11th Day of November, at 11 A.M. race, age, national origin, or profession, they in 1918. On November 11th of the following share a common love for our great nation; a year, President Woodrow Wilson declared that love great enough to put their very lives on the day as “Armistice Day” in honor of the peace. -

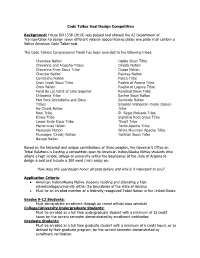

How Does This Seal Design Honor All Code Talkers and Why Is It Important to You?

Code Talker Seal Design Competition Background: House Bill 1338 (2019) was passed and allowed the AZ Department of Transportation to design seven different veteran special license plates one plate shall contain a Native American Code Talker seal. The Code Talkers Congressional Medal has been awarded to the following tribes: Cherokee Nation Oglala Sioux Tribe Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes Oneida Nation Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe Osage Nation Choctaw Nation Pawnee Nation Comanche Nation Ponca Tribe Crow Creek Sioux Tribe Pueblo of Acoma Tribe Crow Nation Pueblo of Laguna Tribe Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Rosebud Sioux Tribe Chippewa Tribe Santee Sioux Nation Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Seminole Nation Tribes Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate (Sioux) Ho-Chunk Nation Tribe Hopi Tribe St. Regis Mohawk Tribe Kiowa Tribe Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Lower Brule Sioux Tribe Tlingit Tribe Menominee Nation Tonto Apache Tribe Meskwaki Nation White Mountain Apache Tribe Muscogee (Creek) Nation Yankton Sioux Tribe Navajo Nation Based on the historical and unique contributions of these peoples, the Governor’s Office on Tribal Relations is hosting a competition open to American Indian/Alaska Native students who attend a high school, college or university within the boundaries of the state of Arizona to design a seal and include a 300 word (min) essay on: How does this seal design honor all code talkers and why is it important to you? Application Criteria: ñ American Indian/Alaska Native students residing and attending a high school/college/university within