Professional Liability Insurance White Paper William Douglas, ARM-P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Social Welfare Strategies

Throughout the world, societies are reexamining, reforming, and restructuring their social welfare systems. New ways are being sought to manage and finance these systems, and new approaches are being developed that alter the relative roles of government, private business, and individ- uals. Not surprisingly, this activity has triggered spirited debate about the relative merits of the various ways of structuring social welfare systems in general and social security programs in particular. The current changes respond to a vari- ety of forces. First, many societies are ad- justing their institutions to reflect changes in social philosophies about the relative responsibilities of government and the individual. These philosophical changes are especially dramatic in China, the former socialist countries of Eastern Europe, and the former Soviet Union; but The Advantages and Disadvantages they are also occurring in what has tradi- of Different Social Welfare Strategies tionally been thought of as the capitalist West. Second, some societies are strug- by Lawrence H. Thompson* gling to adjust to the rising costs associated with aging populations, a problem particu- The following was delivered by the author to the High Level American larly acute in the OECD countries of Asia, Meeting of Experts on The Challenges of Social Reform and New Adminis- Europe, and North America. Third, some trative and Financial Management Techniques. The meeting, which took countries are adjusting their social institu- tions to reflect new development strate- place September 5-7, 1994, in Mar de1 Plata, Argentina, was sponsored gies, a change particularly important in by the International Social Security Association at the invitation of the those countries in the Americas that seek Argentine Secretariat for Social Security in collaboration with the ISSA economic growth through greater eco- Member Organizations of that country. -

IUPAT Pension Summary Plan Description

SUMMARY PLAN DESCRIPTION of the INTERNATIONAL PAINTERS AND ALLIED TRADES INDUSTRY PENSION PLAN (United States) As Amended and Restated to January 2015 INTERNATIONAL PAINTERS AND ALLIED TRADES Industry Pension Plan To All Employees and Plan Participants: The Board of Trustees for the International Painters and Allied Trades Industry Pension Plan, also referred to as the IUPAT Industry Pension Plan, is pleased to provide you with this Summary Plan Description (SPD) of the Rules and Regulations of your Pension Plan. The Pension Plan has been restated as of January 2015 to comply with IRS requirements for qualified pension plans. It is important to note that the retirement eligibility dates and formula to calculate the amount of pension benefits in this document applies only to Active Employees in the Plan on or after January 1, 2012. All other provisions of this booklet are applicable to all participants in the Plan. If you are not an Active Employee in the Plan on or after January 1, 2012, your benefits may be limited by the Plan in effect when you worked in contributory employment under the Plan. If this booklet does not apply to your situation, please contact the Fund Office for the correct version. The SPD incorporates the main features of the amended Plan. As you read through it, you will learn how you become a Plan participant, when you become vested so that you can receive benefits even if you leave work under the Plan, what your benefits are, and how they are calculated. We have tried to describe the Plan's provisions as clearly as possible in a plain and straightforward manner. -

Insurance Summary Plan Description

Summary Plan Description Effective January 1, 2018 Ohio Laborers’ District Council - Ohio Contractors’ Association Insurance Fund Ohio Laborers’ District Council – Ohio Contractors’ Association Insurance Fund 800 Hillsdowne Road Westerville, OH 43081-3302 (614) 898-9006 or (800) 236-6437 Fax: (614) 898-9176 www.olfbp.com [email protected] Dear Member: We are pleased to provide you with this Plan Document/Summary Plan Description (“SPD”). This booklet describes all the benefits provided to you by the Ohio Laborers’ District Council – Ohio Contractors’ Association Insurance Fund (“Fund”). Please read this booklet carefully, share it with your family, and reference it when you have questions regarding your insurance benefits. If you have any questions about the information contained in this booklet or about your insurance benefits in general, please don’t hesitate to contact the OLFBP Fund Office. Sincerely, OLFBP and the Board of Trustees 1 Table of Contents Schedule of Benefits ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 13 Contact Information ................................................................................................................................................. 13 Updating Your Address ........................................................................................................................................... -

Model Insurance Requirements for a Commercial Mortgage Loan

Model Insurance Requirements For A Commercial Mortgage Loan James E. Branigan and Joshua Stein Commercial buildings make good collateral for a lender.They make even better collateral when properly insured against damage and destruction. ⅥⅥⅥ REAL ESTATE LOANS START FROM the A fire or other loss affecting the borrower’s fundamental assumption that the borrower’s building can undercut this very fundamental assumption and throw the loan into default building will continue to exist. As long as the rather quickly—unless the borrower has main- building exists, it can produce rental income so tained an appropriate package of insurance cov- the borrower can pay debt service. erage for the mortgaged property. James E. Branigan, President and Chief Executive Officer of Omega Risk Management LLC, has spoken extensively on insurance and risk management for bar associations and major law firms. His firm is a consultancy, which does not sell insurance. He can be reached at (631) 692-9866 or [email protected]. Joshua Stein, a partner in the New York office of Latham & Watkins LLP, is a member of the American College of Real Estate Lawyers, First Vice Chair of the New York State Bar Association Real Property Law Section, and author of New York Commercial Mortgage Transactions (Aspen 2002), A Practical Guide to Real Estate Practice (ALI-ABA 2001), and over 100 articles about commercial real estate law and prac- tice. He can be reached at (212) 906-1342 or [email protected]. An earlier version of this article appeared in The Real Estate Finance Journal 10 (Winter 2004) , and in Joshua Stein’s recent Mortgage Bankers Association book, Lender’s Guide to Structuring and Closing Commercial Mortgage Loans. -

Guidance Notes

Guidance Notes Application for Registration as an Elector in a Functional Constituency and as a Voter in an Election Committee Subsector Insurance Registration and Electoral Office REO-GN1(2004)-Insu CONTENTS Page Number I. Introduction 1 II. Who is Eligible to Apply for Registration in the 2 Insurance Functional Constituency and its Corresponding Election Committee Subsector III. Who is Disqualified from being Registered 3 IV. How to Submit an Application 4 V. Further Enquiries 4 VI. Personal Information Collection Statement 5 VII. Language Preference for Election-related 5 Communications Appendix A List of Functional Constituencies and their 6 corresponding Election Committee Subsectors Appendix B Eligibility for registration in the Insurance 7 Functional Constituency and its corresponding Election Committee Subsector ******************************************************************** The Guidance Notes and application forms are obtainable from the following sources: (a) Registration and Electoral Office: (i) 10th Floor, Harbour Centre 25 Harbour Road Wan Chai Hong Kong (ii) 10th Floor, Guardian House 32 Oi Kwan Road Wan Chai Hong Kong (b) Registration and Electoral Office Website: www.info.gov.hk/reo/index.htm (c) Registration and Electoral Office Enquiry Hotline: 2891 1001 - 1 - I. Introduction If your body is eligible, your body may apply to be registered as :- an elector in this Functional Constituency (“FC”) and a voter in the corresponding subsector of the Election Committee (“EC”), i.e. a subsector having the same name as the FC, at the same time, OR an elector in this FC and a voter in ONE of the following EC subsectors, instead of in its corresponding EC subsector: (1) Employers’ Federation of Hong Kong; (2) Hong Kong Chinese Enterprises Association; (3) Social Welfare (the part for the corporate bodies only), OR an elector in ONE of the FCs listed in Appendix A, and a voter in either its corresponding EC subsector or ONE of the above EC subsectors. -

Insurance & Reinsurance Law Report

2016 INSURANCE & REINSURANCE LAW REPORT 2016 INSURANCE & REINSURANCE LAW REPORT An Honor Most Sensitive: Duties of Mutual Company Directors in the Context of Significant Strategic Transactions By Daniel J. Neppl and Sean M. Carney ����������������������������������������������������������������������������1 Is the Supreme Court “Pro-Arbitration”? The Answer is More Complicated Than You Think By Susan A. Stone and Daniel R. Thies ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10 Remedies for the Rogue Arbitrator By William M. Sneed ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 16 Unringing the Bellefonte?— New Developments Regarding the Cost-Inclusiveness of Facultative Certificate Limits By Alan J. Sorkowitz �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������22 Biographies .........................................................................................................................28 The Insurance & Reinsurance Law Report is published by the global Insurance and Financial Services group of Sidley Austin LLP� This newsletter reports recent developments of interest to the insurance and reinsurance industry and should not be considered as legal advice or legal opinion on specific facts� Any views or opinions expressed in the newsletter do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Sidley Austin LLP or its clients� Sidley Austin LLP is one of the world’s premier law firms with -

Casework in a Congressional Office: Background, Rules, Laws, and Resources

Casework in a Congressional Office: Background, Rules, Laws, and Resources Updated April 1, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33209 Casework in a Congressional Office: Background, Rules, Laws, and Resources Summary In a congressional office, the term casework refers to the response or services that Members of Congress provide to constituents who request assistance. Each year, thousands of constituents turn to Members of Congress with a wide range of requests, from the simple to the complex. Members and their staffs help constituents deal with administrative agencies by acting as facilitators, ombudsmen, and, in some cases, advocates. In addition to serving individual constituents, some congressional offices also consider as casework liaison activities between the federal government and local governments, businesses, communities, and nonprofit organizations. Members of Congress determine the scope of their constituent service activities. Casework is conducted for various reasons, including a broadly held understanding among Members and staff that casework is integral to the representational duties of a Member of Congress. Casework activities may also be viewed as part of an outreach strategy to build political support, or as an evaluative stage of the legislative process. Constituent inquiries about specific policies, programs, or benefits may suggest areas where government programs or policies require institutional oversight or legislative consideration. One challenge to congressional casework is the widely held public perception that Members of Congress can initiate a broad array of actions resulting in a speedy, favorable outcome. The rules of the House and Senate, and laws and regulations governing federal executive agency activities, however, closely limit interventions made on the behalf of constituents. -

Environmental Insurance for Brownfields Redevelopment: a Feasibility Study

Environmental Insurance for Brownfields Redevelopment: A Feasibility Study FOREWORD Many American cities are now fiscally and economically stronger than they have been in years. However, the task of revitalizing America’s cities remains unfinished, as does the challenge of pursuing sustainable development across metro areas and balancing the need for new growth with smart reinvestments in already developed urban areas. Returning urban brownfields to productive community use is a central aspect of both aims. Towards this end, the Department is a principal partner in the Administration’s initiative to help communities clean up and sustainably redevelop brownfields--a priority for State and local elected officials. Our tools include a new Brownfields Economic Development Initiative (BEDI) to specifically address brownfields redevelopment needs, participating in the Administration’s Showcase Communities Initiative, providing technical assistance to State and local governments, and streamlining community development regulations to make them “friendly” to brownfields redevelopment. Expanding our knowledge base and developing new tools is a vital part of our commitment. Consequently, the Office of Policy Development and Research has initiated an active brownfields research and development program. The purpose of our brownfields R&D work is to better understand how brownfields become barriers to revitalization of America’s distressed communities and to develop ways to overcome or eliminate those barriers. We are examining a range of issues: how the linked issues of environmental risk and neighborhood economic distress affect the redevelopment process, how the Community Development Block Grant program supports local brownfields revitalization efforts, how to pursue and reward innovative approaches for financing brownfields cleanup and development activities, what kinds of state initiatives work and don’t work, and in this report-- how a new insurance tool could help. -

Election Committee

Annex B Election Committee (EC) Subsectors Allocation of seats and methods to return members (According to Annex I to the Basic Law as adopted by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on 30 March 2021) Legend: - Elect.: EC members to be returned by election - Nom: EC members to be returned by nomination - Ex-officio: ex-officio members - Ind: Individual - new: new subsector Composition Remarks/Changes as No. Subsectors Seats Methods Ind Body compared to the 2016 EC First Sector 1 Industrial (first) 17 Elect 2 Industrial (second) 17 Elect Each subsector reduced by 1 3 Textiles and garment 17 Elect seat 4 Commercial (first) 17 Elect 5 Commercial (second) 17 Elect Commercial (third) (former Elect Hong Kong Chinese 6 17 Increased by 1 seat Enterprises Association renamed) 7 Finance 17 Elect 8 Financial services 17 Elect 9 Insurance 17 Elect 10 Real estate and construction 17 Elect 11 Transport 17 Elect 12 Import and export 17 Elect Each subsector reduced by 1 13 Tourism 17 Elect seat 14 Hotel 16 Elect 15 Catering 16 Elect 16 Wholesale and retail 17 Elect Employers’ Federation of Elect 17 15 Hong Kong 18 Small and medium Elect 15 enterprises (new) Composition Remarks/Changes as No. Subsectors Seats Methods Ind Body compared to the 2016 EC Second Sector Nominated from among Technology and innovation Hong Kong academicians of (new) Nom 15 the Chinese Academy of 19 30 (Information technology Sciences and the Chinese subsector replaced) Academy of Engineering Elect 15 Responsible persons of Ex- statutory -

2019 Insurance Fact Book

2019 Insurance Fact Book TO THE READER Imagine a world without insurance. Some might say, “So what?” or “Yes to that!” when reading the sentence above. And that’s understandable, given that often the best experience one can have with insurance is not to receive the benefits of the product at all, after a disaster or other loss. And others—who already have some understanding or even appreciation for insurance—might say it provides protection against financial aspects of a premature death, injury, loss of property, loss of earning power, legal liability or other unexpected expenses. All that is true. We are the financial first responders. But there is so much more. Insurance drives economic growth. It provides stability against risks. It encourages resilience. Recent disasters have demonstrated the vital role the industry plays in recovery—and that without insurance, the impact on individuals, businesses and communities can be devastating. As insurers, we know that even with all that we protect now, the coverage gap is still too big. We want to close that gap. That desire is reflected in changes to this year’s Insurance Information Institute (I.I.I.)Insurance Fact Book. We have added new information on coastal storm surge risk and hail as well as reinsurance and the growing problem of marijuana and impaired driving. We have updated the section on litigiousness to include tort costs and compensation by state, and assignment of benefits litigation, a growing problem in Florida. As always, the book provides valuable information on: • World and U.S. catastrophes • Property/casualty and life/health insurance results and investments • Personal expenditures on auto and homeowners insurance • Major types of insurance losses, including vehicle accidents, homeowners claims, crime and workplace accidents • State auto insurance laws The I.I.I. -

Members' Allowances and Services Manual

MEMBERS’ ALLOWANCES AND SERVICES Table of Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1-1 2. Governance and Principles ....................................................................................... 2-1 1. Introduction ................................................................................................. 2-2 2. Governing Principles .................................................................................... 2-2 3. Governance Structure .................................................................................. 2-6 4. House Administration .................................................................................. 2-7 3. Members’ Salary and Benefits .................................................................................. 3-1 1. Introduction ................................................................................................. 3-2 2. Members’ Salary .......................................................................................... 3-2 3. Insurance Plans ............................................................................................ 3-3 4. Pension ........................................................................................................ 3-5 5. Relocation .................................................................................................... 3-6 6. Employee and Family Assistance Program .................................................. 3-8 7. -

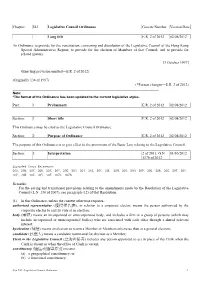

Constituency (選區或選舉界別) Means- (A) a Geographical Constituency; Or (B) a Functional Constituency;

Chapter: 542 Legislative Council Ordinance Gazette Number Version Date Long title E.R. 2 of 2012 02/08/2012 An Ordinance to provide for the constitution, convening and dissolution of the Legislative Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; to provide for the election of Members of that Council; and to provide for related matters. [3 October 1997] (Enacting provision omitted—E.R. 2 of 2012) (Originally 134 of 1997) (*Format changes—E.R. 2 of 2012) _______________________________________________________________________________ Note: *The format of the Ordinance has been updated to the current legislative styles. Part: 1 Preliminary E.R. 2 of 2012 02/08/2012 Section: 1 Short title E.R. 2 of 2012 02/08/2012 This Ordinance may be cited as the Legislative Council Ordinance. Section: 2 Purpose of Ordinance E.R. 2 of 2012 02/08/2012 The purpose of this Ordinance is to give effect to the provisions of the Basic Law relating to the Legislative Council. Section: 3 Interpretation 2 of 2011; G.N. 01/10/2012 5176 of 2012 Expanded Cross Reference: 20A, 20B, 20C, 20D, 20E, 20F, 20G, 20H, 20I, 20J, 20K, 20L, 20M, 20N, 20O, 20P, 20Q, 20R, 20S, 20T, 20U, 20V, 20W, 20X, 20Y, 20Z, 20ZA, 20ZB Remarks: For the saving and transitional provisions relating to the amendments made by the Resolution of the Legislative Council (L.N. 130 of 2007), see paragraph (12) of that Resolution. (1) In this Ordinance, unless the context otherwise requires- authorized representative (獲授權代表), in relation to a corporate elector, means the person authorized by the