Dynamic Optimization of a Subcritical Steam Power Plant Under Time-Varying Power Load

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Organic Vapor Cycles for Improving Thermal Conversion Efficiency in Renewable Energy Systems by Tony Ho a Dissertation

Advanced Organic Vapor Cycles for Improving Thermal Conversion Efficiency in Renewable Energy Systems By Tony Ho A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Engineering – Mechanical Engineering in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ralph Greif, Co-Chair Professor Samuel S. Mao, Co-Chair Professor Van P. Carey Professor Per F. Peterson Spring 2012 Abstract Advanced Organic Vapor Cycles for Improving Thermal Conversion Efficiency in Renewable Energy Systems by Tony Ho Doctor of Philosophy in Mechanical Engineering University of California, Berkeley Professor Ralph Greif, Co-Chair Professor Samuel S. Mao, Co-Chair The Organic Flash Cycle (OFC) is proposed as a vapor power cycle that could potentially increase power generation and improve the utilization efficiency of renewable energy and waste heat recovery systems. A brief review of current advanced vapor power cycles including the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC), the zeotropic Rankine cycle, the Kalina cycle, the transcritical cycle, and the trilateral flash cycle is presented. The premise and motivation for the OFC concept is that essentially by improving temperature matching to the energy reservoir stream during heat addition to the power cycle, less irreversibilities are generated and more power can be produced from a given finite thermal energy reservoir. In this study, modern equations of state explicit in Helmholtz energy such as the BACKONE equations, multi-parameter Span- Wagner equations, and the equations compiled in NIST REFPROP 8.0 were used to accurately determine thermodynamic property data for the working fluids considered. Though these equations of state tend to be significantly more complex than cubic equations both in form and computational schemes, modern Helmholtz equations provide much higher accuracy in the high pressure regions, liquid regions, and two-phase regions and also can be extended to accurately describe complex polar fluids. -

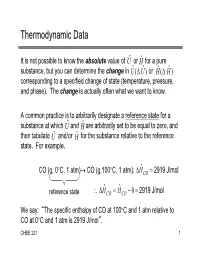

Thermodynamic Data

Thermodynamic Data It is not possible to know the absolute value of U ˆ or H ˆ for a pure substance, but you can determine the change in U ˆ ( U ˆ ) or Hˆ ( Hˆ ) corresponding to a specified change of state (temperature, pressure, and phase). The change is actually often what we want to know. A common practice is to arbitrarily designate a reference state for a substance at which U ˆ and H ˆ are arbitrarily set to be equal to zero, and then tabulate U ˆ and/or H ˆ for the substance relative to the reference state. For example, ˆ CO (g, 0C, 1 atm) CO (g,100C, 1 atm): HCO 2919 J/mol ˆ ˆ reference state HCO HCO 0 2919 J/mol We say: “The specific enthalpy of CO at 100C and 1 atm relative to CO at 0C and 1 atm is 2919 J/mol”. CHEE 221 1 Reference States and State Properties Most (all?) enthalpy tables report the reference states (T, P and State) on which the values of H ˆ are based; however, it is not necessary to know the reference state to calculate H (change in enthalpy) for the transition from one state to another. ˆ ˆ –H from state 1 to state 2 equals H 2 H 1 regardless of the reference state upon which ˆ and ˆ were based H1 H 2 – Caution: If you use different tables, you must make sure they have the same reference state This result is a consequence of the fact that H ˆ (and U ˆ ) are state properties, that is, their values depend only on the state of the species (temperature, pressure, state) and not on how the species reached its state. -

Backpressure Steam Power Generation in District Energy and CHP - Energy Efficiency Considerations

Backpressure Steam Power Generation in District Energy and CHP - Energy Efficiency Considerations A 1st Law, 2nd Law and Economic Analysis of the Practical Steam Engine in a District Energy/CHP Application Joshua A. Tolbert, Ph.D. Practical Steam Energy Efficiency Engineering – How is efficiency calculated? • What is the Status Quo? – Engineers currently focus on limiting energy losses as the primary point of focus for district energy and CHP systems – Only local energy losses are typically considered causing energy efficiency opportunities to be wasted • Why? – Conventional wisdom tells us that minimizing local energy losses is ultimate goal • How should we change? – Could a different approach improve global efficiency? Motivation Common Questions: 1. How can installing an imperfect device in parallel to an isenthalpic pressure reducing valve (PRV) improve efficiency? 2. My analysis shows an incremental fuel cost with PRV parallel, how can this be more efficient? Analysis Overview • Consider a Practical Steam Engine (PSE) in a Pressure Reducing Valve (PRV) parallel district energy application • PSE operation is consistent with CHP application • Consider 1st Law, 2nd Law and economic analysis for energy efficiency • Draw conclusions Backpressure Application – Case Study Enwave Seattle - District Energy / CHP Application Assumptions Equipment • 1.5 MW (5.118 MMBtu/hr) • Practical Steam Engine (PSE) heating load is considered o Isentropic efficiency of 80% • Condensate exiting load: o Mechanical efficiency of 80% Saturate liquid at 20 psig o Generator efficiency of 95% • No heat losses in piping or • Isenthalpic PRV equipment* • 150 psig saturated steam boiler • 80% boiler and feedwater pump efficiency *Incorporating actual heat losses does not significantly affect results of analysis. -

Superheated Steam in Locomotive Service

I LL INO I S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. 0 ~0' / ~ ( ~ 1~CC~& '~f~LW "0~ "N ~ ~- ~N~TV N Q SC 2"' C' ''~~C'~ C" 4 AA.A..~ Ay ~4.A A A'-' 'A ' ~ ' ,~A~A 1 A' 'A": "I ~' ~A 9 ~AA >' 0 -A.'-- ~ A" Z 'A A' * A -A "* K~ A. A' ~. 'A A, ,~, 'U",' 4 *, A' '~'" 'A * JA A' 'A' A A K 'A 'A / A A A' 'A vas,^esta>bflibea~ ~ by ^f'A A' A ,rt~7B A 'A on, investigations~ve~Wg~on.~. A' ~ 'i* *t~.,to studysti~dy~ prob1~m~problems A sS ~4 IOAWeto eadA manu-m&i~n- 'be industrial interests 'A' of theb8tat;' -'$a te' The control of tho Engineering ExperintSerment• 'titionSl i•is is'vested vested 'A UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS ENGINEERING EXPERIMENT STATION BULLETIN No. 57 APRIL 1912 SUPERHEATED STEAM IN LOCOMOTIVE SERVICE (A REVIEW OF PUBLICATION NO. 127 OF THE CARNEGIE INSTITUTION OF WASHINGTON) BY W. F. M. GOSS DEAN OF THE COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING DIRECTOR OF THE ENGINEERING EXPERIMENT STATION DIRECTOR OF THE SCHOOL OF RAILWAY ENGINEERING AND ADMINISTRATION CONTENTS PAGE I. Introduction-A Summary of Conclusions .......... 3 II. Foreign Practice in the Use of Superheated Steam in Locomotive Service.............. ......... 5 III. Tests to Determine the Value of Superheating in Lo- comotive Service................ .. .. .... 14 IV. Performance of Boiler and Superheater.. ........... 20 V. Performance of the Engine and of the Locomotive as a W hole... ............ .. .. ........ 35 VI. Economy Resulting from the Use of Superheated Steam ........... -

Improve Performance and Efficiency of the Steam Power Plant

First Scientific Conference on Petroleum Resources and Manufacturing 27-28 October 2010 Brega, Libya Improve Performance and Efficiency of the Steam Power Plant Hesham G. Ibrahim1, Aly Y. Okasha2 and Ahmed G. Elkhalidy3 1Chemical Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Misurata University, Al-Khoms City, Libya. Tel.: ++218-338-9965, e-mail: [email protected] 2Environmental Department, Faculty of Science, Misurata University, Al-Khoms City, Libya Tel.:++218-91-344-6102, e-mail: [email protected] 3Life Tech. Company, Manchester City, UK ABSTRACT Power plants generate electrical power by using fuels like coal, oil or natural gas. Fuel burned in the boiler to heats water to generate steam. The steam is then heated to a superheated state in the superheater. This superheated steam is used to rotate the turbine which powers the generator. Electrical energy is generated when the generator windings rotate in a strong magnetic field. After the steam leaves the turbine it is cooled to its liquid state in the condenser. The liquid is pressurized by the pump prior to going back to the boiler. This simple power plant is called (steam power plant). This cycle has a problem represent through a steam leaves the turbine, it is typically wet. The presence of water causes erosion of the turbine blades at high speed, gradually decreasing the life of turbine blades and efficiency of the turbine. That's leading to damage of turbine then shut-off plant. So, a simulation process of steam power plant done using (Hysys v.3.2) to improve the performance of plant also increasing efficiency through prevent erosion occurs and decreasing heat loses by condenser. -

Consider Installing High-Pressure Boilers with Backpressure Turbine-Generators

Energy Tips – Steam Steam Tip Sheet #22 • September 2004 Industrial Technologies Program Background Consider Installing High-Pressure Boilers with The capital cost of a back- Backpressure Turbine-Generators pressure turbogenerator complete with electrical When specifying a new boiler, consider a high-pressure boiler with a backpressure switchgear varies from steam turbine-generator placed between the boiler and the steam distribution about $700/kW for a small network. A turbine-generator can often produce enough electricity to justify the system (50 kW) to less than capital cost of purchasing the higher-pressure boiler and the turbine-generator. $200/kW for a larger system (>2,000 kW). Installation Since boiler fuel usage per unit of steam production increases with boiler pressure, costs vary depending upon facilities often install boilers that produce steam at the lowest pressure consistent with piping and wiring runs, but end use and distribution requirements. typically average 75% of equipment costs. In the backpressure turbine configuration, the turbine does not consume steam. Instead, it simply reduces the pressure and energy content of steam that is subsequently exhausted into the process header. In essence, the turbo-generator Packaged or “off-the-shelf” serves the same steam function as a pressure-reducing valve (PRV)—it reduces steam backpressure turbogenerators pressure—but uses the pressure drop to produce highly valued electricity in addition are now available in ratings as to the low-pressure steam. Shaft power is produced when a nozzle directs jets of low as 50 kW. Backpressure high-pressure steam against the blades of the turbineʼs rotor. The rotor is attached to a turbogenerators should be shaft that is coupled to an electrical generator. -

An Integrated Study of Flue Gas Flow and Superheating Process in Recovery Boiler Using Computational Fluid Dynamics and 1D-Process Modelling

An Integrated Study of Flue Gas Flow and Superheating Process in Recovery Boiler using Computational Fluid Dynamics and 1D-Process Modelling Kunal Kumar Andritz Oy, Viljami Maakala Andritz Oy and Ville Vuorinen Aalto University ABSTRACT Superheaters are the last heat exchangers on the steam side in recovery boilers. They are typically made of expensive materials due to the high steam temperature and risks associated with ash-induced corrosion. Therefore, detailed knowledge about the steam properties and material temperature distribution is essential for improving the energy efficiency, cost efficiency and safety of recovery boilers. In this work, for the first time, a comprehensive 1D-process model (1D-PM) for superheated steam cycle is developed and linked with a full-scale 3D CFD (computational fluid dynamics) model of the superheater region flue gas flow. The results indicate that first; the geometries of headers and superheater platens affect platen-wise steam distribution. Second, the CFD solution of the 3D flue gas flow field and platen heat flux distribution coupled with the 1D-PM affect the generated superheated steam properties and material temperature distribution. These new observations clearly demonstrate the value of the present integrated CFD/1D-PM modelling approach. It is advantageous for trouble shooting, optimizing the performance of superheaters and selecting their design margins for the future. The developed integrated modelling approach could also be relevant for other large-scale energy production units such as biomass-fired boilers. 1 INTRODUCTION Recovery boilers are used to combust black liquor for chemical recovery and producing high-pressure superheated steam. The generated steam is utilized for self-sustainable pulp mill operations and electricity generation. -

Thermodynamics

ME 201 Thermodynamics ME 201 Thermodynamics Old Exam #2 Solutions Directions: Work all three (3) problems. The exam is open notes and open text book. All problems have equal weight. Problem 1 A rigid container holds 3 kg of air initially at 50°C. The air is stirred so that its pressure changes from 500 kPa to 2000 kPa. The heat transfer is 200 kJ. Determine the final temperature, the change in internal energy, and the work. Solution: Using our 1st law template, we carefully read the problem and enter the given information. System Type: Closed (container) Substance Type: Ideal Gas (air) Process Type: Isotropic (rigid) State 1: Fixed State 2: Not fixed Q = 200 kJ Wsh = ??? Wbnd = 0 Conservation of Mass: m1 = m2 Conservation of Energy: m1u2 - u1 = Q - Wsh State 1 State 2 T1 = 50C = 323 K T2 = 1292 K P1 = 500 kPa P2 = 2000 kPa 3 3 v1 = 0.1854 m /kg v2 = 0.1854 m /kg 3 3 V1 = 0.5562 m V2 = 0.5562 m u1 = 230.58 kJ/kg u2 = 1015.6 kJ/kg m1 = 3 kg m2 = 3 kg Bold values are calculated. Italicized values are from tables or ideal gas law. Approach: Use the air tables and ideal gas law to determine the properties for state 1. Use the mass to calculate V1. Use the isotropic condition to fix state 2, then use the tables to determine the properties. Finally, calculate the shaft work from the 1st law. From the air tables we find u1 = 230.58 kJ/kg From the ideal gas law we have RT1 (0.287 )(323) 3 v1 = 0.1854 m /kg P1 (500) 1 ME 201 Thermodynamics Then by definition 3 V1 mv 1 = (3)(0.1854) 0.5562 m Since our process is isotropic 3 V2 = V1 = 0.5562 m and 3 v2 = v1 = 0.1854 m /kg Solving for the state 2 temperature from the ideal gas law P v (2000 )(0.1854 ) T 1 1 = 1292 K 1 R (0.287 ) From the air tables we now find u2 = 1015.6 kJ/kg Solving for the shaft work form the 1st law Wsh = Q - m1 u 2 - u1 200 - (3)(1015.6 - 230.58) - 2155 kJ Problem 2 A desuperheater is an adiabatic mixing tank which produces saturated vapor from a superheated vapor by adding liquid. -

Superheated Steam Temperature and Heat SCIENTIFIC

Superheated Steam Temperature and Heat SCIENTIFIC Introduction Why is steam a greater skin-burning threat than boiling water? How much energy is contained in steam? This demonstra- tion will dramatically show the energy content of superheated steam. Concepts • Heat energy • Steam • Condensation Materials Water, 150 mL Meker burner Beaker, any size Rubber stopper with hole, #6 Boiling chips, 2 or 3 Sheets of paper, 2 × 2, 2 Crucible tongs Support stand and clamp Copper coil tubing Support ring or adjustable burner support block Erlenmeyer flask, 250-mL Thermometer (optional) Hot plate Towel Match stick Safety Precautions Superheated steam is very hot. Be sure students are not close to the demonstration apparatus and especially not in the “line of fire” of the jet stream. Hot water and steam will spurt out the open end of the copper tubing during the demonstration. Do not point the exhaust end of the copper coil tubing at anybody. Perform this demonstration on a table that is free of any items that should not get wet. Care should be taken when handling the Meker burner while heating the copper coil. Allow the copper tubing to cool completely before touching or disassembling the apparatus. Wear chemical splash goggles, heat-resistant gloves, and a chemical-resistant apron. Please review current Material Safety Data Sheets for additional safety, handling, and disposal information. Preparation (refer to Figure 1) 1. Carefully insert the bent end of the copper tubing into the hole of the #6 rubber stopper so that the end of the tubing is flush with the bottom of the stopper. -

Carbon Dioxide Mixtures As Working Fluid for High-Temperature Heat Recovery: a Thermodynamic Comparison with Transcritical Organic Rankine Cycles

energies Article Carbon Dioxide Mixtures as Working Fluid for High-Temperature Heat Recovery: A Thermodynamic Comparison with Transcritical Organic Rankine Cycles Abubakr Ayub 1 , Costante M. Invernizzi 1,* , Gioele Di Marcoberardino 1 , Paolo Iora 1 and Giampaolo Manzolini 2 1 Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, University of Brescia, via Branze, 38, 25123 Brescia, Italy; [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (G.D.M.); [email protected] (P.I.) 2 Energy Department, Politecnico di Milano, 20156 Milan, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-030-3715-569 Received: 30 June 2020; Accepted: 24 July 2020; Published: 4 August 2020 Abstract: This study aims to provide a thermodynamic comparison between supercritical CO2 cycles and ORC cycles utilizing flue gases as waste heat source. Moreover, the possibility of using CO2 mixtures as working fluids in transcritical cycles to enhance the performance of the thermodynamic cycle is explored. ORCs operating with pure working fluids show higher cyclic thermal and total efficiencies compared to supercritical CO2 cycles; thus, they represent a better option for high-temperature waste heat recovery provided that the thermal stability at a higher temperature has been assessed. Based on the improved global thermodynamic performance and good thermal stability of R134a, CO2-R134a is investigated as an illustrative, promising working fluid mixture for transcritical power cycles. The results show that a total efficiency of 0.1476 is obtained for the CO2-R134a mixture (0.3 mole fraction of R134a) at a maximum cycle pressure of 200 bars, which is 15.86% higher than the supercritical carbon dioxide cycle efficiency of 0.1274, obtained at the comparatively high maximum pressure of 300 bars. -

Consider Installing High-Pressure Boilers with Backpressure Turbine-Generators, Energy Tips: STEAM, Steam Tip Sheet #22 (Fact Sh

ADVANCED MANUFACTURING OFFICE Energy Tips: STEAM Steam Tip Sheet #22 Consider Installing High-Pressure Boilers with Backpressure Turbine-Generators Suggested Actions Consider installing a high-pressure When specifying a new boiler, consider a high-pressure boiler with a backpressure boiler with a back-pressure turbine- steam turbine-generator placed between the boiler and the steam distribution network. generator whenever undertaking a A turbine-generator can often produce enough electricity to justify the capital cost of boiler upgrade. When evaluating purchasing the higher-pressure boiler and the turbine-generator. this opportunity, you should: Since boiler fuel usage per unit of steam production increases with boiler pressure, facilities often install boilers that produce steam at the lowest pressure consistent with ■■ Determine how much steam end use and distribution requirements. enthalpy, pressure, and In the backpressure turbine configuration, the turbine does not consume steam. Instead, it temperature are required at the simply reduces the pressure and energy content of steam that is subsequently exhausted header downstream from your into the process header. In essence, the turbogenerator serves the same steam function as boiler. a pressure-reducing valve (PRV)—it reduces steam pressure—but uses the pressure drop to produce highly valued electricity in addition to the low-pressure steam. Shaft power ■■ Calculate the incremental fuel is produced when a nozzle directs jets of high-pressure steam against the blades of the cost between a low-pressure turbine’s rotor. The rotor is attached to a shaft that is coupled to an electrical generator. boiler and a high-pressure boiler. Background ■■ Develop steam flow/duration The capital cost of a back-pressure turbogenerator complete with electrical switchgear curves for your boiler. -

Energy Effective and Green Drying Technologies with Industrial Applications , Chemical Engineering Transactions, 70, 145-150 DOI:10.3303/CET1870025 146

145 A publication of CHEMICAL ENGINEERING TRANSACTIONS VOL. 70, 2018 The Italian Association of Chemical Engineering Online at www.aidic.it/cet Guest Editors: Timothy G. Walmsley, Petar S. Varbanov, Rongxin Su, Jiří J. Klemeš Copyright © 2018, AIDIC Servizi S.r.l. ISBN 978-88-95608-67-9; ISSN 2283-9216 DOI: 10.3303/CET1870025 Energy Effective and Green Drying Technologies with Industrial Applications Odilio Alves-Filho Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Department of Energy and Process Engineering, Kolbjørn Hejes vei 1b, 7491 Trondheim, Norway [email protected] Heat pump drying is a green technology with zero global warming potential and zero ozone depletion potential when operating with natural fluids. A well designed heat pump dryer can be several times more energy efficient and less costly than conventional dryers. This dryer beneficially contributes to a sustainable society while providing superior products at competitive cost. It is an advanced engineered drying technology ready for implementation by modern industries wishing a return of investment while contributing to a sustainable society. This paper covers the advances in heat pump and superheated steam drying technologies. These drying processes are in the category of green technologies because they are highly effective and advantageous for the environment and climate change. Descriptions and layouts are given covering design of heat pump and steam dryers. Details are provided in their beneficial operation in single and multistage with vapor compression and drying chambers placed in series. The drying modes covered are atmospheric sublimation and evaporation for improved capacity and superior characteristics of dried materials. The future trend is heat pump drying with natural fluids and superheated steam drying complying with proper industrial practice and with regulations reducing damage to sea, soil and water as well as zeroing contribution to global warming and to climate change.