126613709.23.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

126613853.23.Pdf

Sc&- PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME LIV STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH OCTOBEK 190' V STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH 1225-1559 Being a Translation of CONCILIA SCOTIAE: ECCLESIAE SCOTI- CANAE STATUTA TAM PROVINCIALIA QUAM SYNODALIA QUAE SUPERSUNT With Introduction and Notes by DAVID PATRICK, LL.D. Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1907 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION— i. The Celtic Church in Scotland superseded by the Church of the Roman Obedience, . ix ir. The Independence of the Scottish Church and the Institution of the Provincial Council, . xxx in. Enormia, . xlvii iv. Sources of the Statutes, . li v. The Statutes and the Courts, .... Ivii vi. The Significance of the Statutes, ... lx vii. Irreverence and Shortcomings, .... Ixiv vni. Warying, . Ixx ix. Defective Learning, . Ixxv x. De Concubinariis, Ixxxvii xi. A Catholic Rebellion, ..... xciv xn. Pre-Reformation Puritanism, . xcvii xiii. Unpublished Documents of Archbishop Schevez, cvii xiv. Envoy, cxi List of Bishops and Archbishops, . cxiii Table of Money Values, cxiv Bull of Pope Honorius hi., ...... 1 Letter of the Conservator, ...... 1 Procedure, ......... 2 Forms of Excommunication, 3 General or Provincial Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 8 Aberdeen Synodal Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 30 Ecclesiastical Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, . 46 Constitutions of Bishop David of St. Andrews, . 57 St. Andrews Synodal Statutes of the Fourteenth Century, vii 68 viii STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH Provincial and Synodal Statute of the Fifteenth Century, . .78 Provincial Synod and General Council of 1420, . 80 General Council of 1459, 82 Provincial Council of 1549, ...... 84 General Provincial Council of 1551-2 ... -

Phases of Irish History

¥St& ;»T»-:.w XI B R.AFLY OF THE UNIVERSITY or ILLINOIS ROLAND M. SMITH IRISH LITERATURE 941.5 M23p 1920 ^M&ii. t^Ht (ff'Vj 65^-57" : i<-\ * .' <r The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. University of Illinois Library • r m \'m^'^ NOV 16 19 n mR2 51 Y3? MAR 0*1 1992 L161—O-1096 PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY ^.-.i»*i:; PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY BY EOIN MacNEILL Professor of Ancient Irish History in the National University of Ireland M. H. GILL & SON, LTD. so UPPER O'CONNELL STREET, DUBLIN 1920 Printed and Bound in Ireland by :: :: M. H. Gill &> Son, • • « • T 4fl • • • JO Upper O'Connell Street :: :: Dttblin First Edition 1919 Second Impression 1920 CONTENTS PACE Foreword vi i II. The Ancient Irish a Celtic People. II. The Celtic Colonisation of Ireland and Britain . • • • 3^ . 6i III. The Pre-Celtic Inhabitants of Ireland IV. The Five Fifths of Ireland . 98 V. Greek and Latin Writers on Pre-Christian Ireland . • '33 VI. Introduction of Christianity and Letters 161 VII. The Irish Kingdom in Scotland . 194 VIII. Ireland's Golden Age . 222 IX. The Struggle with the Norsemen . 249 X. Medieval Irish Institutions. • 274 XI. The Norman Conquest * . 300 XII. The Irish Rally • 323 . Index . 357 m- FOREWORD The twelve chapters in this volume, delivered as lectures before public audiences in Dublin, make no pretence to form a full course of Irish history for any period. -

February Magazine Web

Rector Rev Kirstin Freeman February 2020 Magazine E-mail [email protected] Other contacts can be found on the printed copy in the church Web Site: http://bearsden.church.scot Web Site Co-ordinator: Janet Stack ([email protected]) All Saints is a registered charity in Scotland SCO005552 Cover picture : Rt Revd Kevin Pearson our bishop-elect All Saints Scottish Episcopal Church Drymen Road, Bearsden £1 A new bishop for the Diocese already know many in the Diocese but are also looking forward to living there and getting to know the people and the area better. We shall be very sad to be leaving The Right Reverend Kevin Pearson was elected as the new Bishop of Glasgow and the people of Argyll and The Isles which we have grown to love deeply over nine Galloway, on Saturday 18 th January. Bishop Kevin is currently the Bishop of Argyll years of ministry there.” and The Isles and his election to Glasgow and Galloway represents a historic Bishop Kevin is married to Dr Elspeth Atkinson who is Chief Operating Officer for the “translation” of a Bishop from one See to another. Bishop Kevin will take up his new Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St Andrews & Edinburgh. Prior to that Elspeth was post at a service of installation later in the year, on a date to be announced in due Director of MacMillan Cancer Support in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales and course. for most of her career held senior roles in Economic Development in Scotland. Bishop Kevin has served as Bishop of Argyll and The Isles since February 2011 and before that was Rector of St Michael & All Saints Church in Edinburgh, Canon of St Requiem a nd Service of Dedication Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh, Dean of the Diocese of Edinburgh and the Provincial Director of Ordinands. -

Catalogue Description and Inventory

= CATALOGUE DESCRIPTION AND INVENTORY Adv.MSS.30.5.22-3 Hutton Drawings National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © 2003 Trustees of the National Library of Scotland = Adv.MSS.30.5.22-23 HUTTON DRAWINGS. A collection consisting of sketches and drawings by Lieut.-General G.H. Hutton, supplemented by a large number of finished drawings (some in colour), a few maps, and some architectural plans and elevations, professionally drawn for him by others, or done as favours by some of his correspondents, together with a number of separately acquired prints, and engraved views cut out from contemporary printed books. The collection, which was previously bound in two large volumes, was subsequently dismounted and the items individually attached to sheets of thick cartridge paper. They are arranged by county in alphabetical order (of the old manner), followed by Orkney and Shetland, and more or less alphabetically within each county. Most of the items depict, whether in whole or in part, medieval churches and other ecclesiastical buildings, but a minority depict castles or other secular dwellings. Most are dated between 1781 and 1792 and between 1811 and 1820, with a few of earlier or later date which Hutton acquired from other sources, and a somewhat larger minority dated 1796, 1801-2, 1805 and 1807. Many, especially the engravings, are undated. For Hutton’s notebooks and sketchbooks, see Adv.MSS.30.5.1-21, 24-26 and 28. For his correspondence and associated papers, see Adv.MSS.29.4.2(i)-(xiii). -

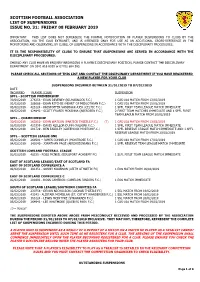

Scottish Football Association List of Suspensions Issue No

SCOTTISH FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION LIST OF SUSPENSIONS ISSUE NO. 31: FRIDAY 08 FEBRUARY 2019 IMPORTANT – THIS LIST DOES NOT SUPERSEDE THE FORMAL NOTIFICATION OF PLAYER SUSPENSIONS TO CLUBS BY THE ASSOCIATION, VIA THE CLUB EXTRANET, AND IS INTENDED ONLY FOR USE AS AN ADDITIONAL CROSS-REFERENCE IN THE MONITORING AND OBSERVING, BY CLUBS, OF SUSPENSIONS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. IT IS THE RESPONSIBILITY OF CLUBS TO ENSURE THAT SUSPENSIONS ARE SERVED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. SHOULD ANY CLUB HAVE AN ENQUIRY REGARDING A PLAYER’S DISCIPLINARY POSITION, PLEASE CONTACT THE DISCIPLINARY DEPARTMENT ON 0141 616 6018 or 07702 864 165. PLEASE CHECK ALL SECTIONS OF THIS LIST AND CONTACT THE DISIPLINARY DEPARTMENT IF YOU HAVE REGISTERED A NEW PLAYER FOR YOUR CLUB SUSPENSIONS INCURRED BETWEEN 31/01/2019 TO 07/02/2019 DATE INCURRED PLAYER (CLUB) SUSPENSION SPFL - SCOTTISH PREMIERSHIP 30/01/2019 276256 - EUAN DEVENEY (KILMARNOCK F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 01/02/2019 386086 - DEAN RITCHIE (HEART OF MIDLOTHIAN F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 15/02/2019 03/02/2019 423124 - KRISTOFFER VASSBAKK AJER (CELTIC F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 124842 - SCOTT FRASER MCKENNA (ABERDEEN F.C.) 2 FIRST TEAM MATCHES IMMEDIATE AND 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH FROM 20/02/2019 SPFL – CHAMPIONSHIP 30/01/2019 260210 - DEAN WATSON (PARTICK THISTLE F.C.) (T) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 02/02/2019 425359 - DAVIS KEILLOR-DUNN (FALKIRK F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 201729 - BEN -

The Diocese of Sodor Between N I Ð Aróss and Avignon – Rome, 1266

Theð diocese of Sodor between Ni aróss and Avignon – Rome, 1266-1472 Sarah E. Thomas THE organisation and administration of the diocese of Sodor has been discussed by a number of scholars, either jointly with Argyll or in relation to 1 ð Norway. In 1266 the diocese of Sodor or Su reyjar encompassed the Hebrides and the Isle of Man, but by the end of the fourteenth century, it was divided between the Scottish Hebrides and English Man. The diocese’s origins lay in the Norseð kingdom of the Isles and Man and its inclusion in the province of Ni aróss can be traced back to the actions of Olaf 2 Godredsson in the 1150s.ð After the Treaty of Perth of 2 July 1266, Sodor remained within the Ni aróss church province whilst secular sovereignty 3 and patronage of the see had been transferred to the King of Scots. However, wider developments in the Christian world and the transfer of allegiance of Hebridean secular ðrulers from Norway to Scotland after 1266 would loosen Sodor’s ties to Ni aróss. This article examines the diocese of Sodor’s relationship with its metropolitan and the rather neglected area of its developing links with the papacy. It argues that the growing 1 A.I. Dunlop, ‘Notes on the Church in the Dioceses of Sodor and Argyll’, Records of the Scottish Church History Society 16 (1968) [henceforth RSCHS]; I.B. Cowan, ‘The Medieval Church in Argyll and the Isles’, RSCHS 20 (1978-80); A.D.M. Barrell, ‘The church in the West Highlands in the late middle ages’, Innes Review 54 (2003); A. -

DRYBURGH ABBEY. an Important William IV Castle Top Snuff Box Made in Birmingham in 1834 by Joseph SOLD Willmore

DRYBURGH ABBEY. An important William IV Castle Top Snuff Box made in Birmingham in 1834 by Joseph SOLD Willmore. REF:- 202302 1 Mary Cooke Antiques Ltd 12 The Old Power Station 121 Mortlake High Street London SW14 8SN 0208 876 5777 https://marycooke.co.uk/dryburgh-abbey-an-important-william-iv-castle-top-snuff-box 03/10/2021 Short Description The Snuff Box is broad rectangular in form with a cast floral and foliate border on both the cover and base. The sides and base are decorated with engine turning and the centre of the base is engraved with J. Pitcher, the gift of Mr Holman, on a rectangular disc cartouche. The interior is finely gilded and displays crisp marks and the cover shows a finely detailed view of Dryburgh Abbey in high relief. The cover also displays the title of the scene in the bottom left hand corner, which is rarely seen on snuff boxes with views on the cover. Dryburgh is a ruined abbey beside the river Tweed between Melrose and Kelso. It is smaller than the nearby abbeys at Jedburgh, Kelso and Melrose. The abbey was established by the Premonstratensian Order in 1150. Sir Walter Scott, the novelist,was buried here on 26th September, 1832, beside some of his ancestors and his wife, who had pre-deceased him in 1826. The quality of this box is outstanding and it is most unusual and very rare to see this view on a Snuff Box. Length: 2.75 inches, 6.88cm Width: 1.75 inches, 4.38cm. Depth: 0.9 inches, 2.25 cm. -

The History of Scotland from the Accession of Alexander III. to The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

Kilwinning-Abbey-By-Ja-Ness.Pdf

John Ness was a keen local historian with a large collection of papers, books, pamphlets, charts and letters about Kilwinning and district, but being before the days of computers and the Internet, collating and editing this booklet would surely have meant many long hours searching through piles of books and notes. It was originally published in 1967, no doubt as part of the Abbey Church’s 400th anniversary celebrations (albeit a year or two late if the dates are correct), and was one of only a few collected sources of information about the Abbey. Of course, it is now long out of print and only a few dog-eared copies exist in libraries, but now it is accessible to the public once more. To make it easier to read on a computer screen, it hasn’t been recreated in its completely original form, but I have more or less kept the same layout. I made a few minor changes, adding a few commas here and there to make the sometimes slightly awkward sentence construction easier to read. If something reads a little strangely to modern eyes, that was the author’s style. Also, I corrected a very few obvious printing errors, and standardised words and phrases that were in bold type for no good reason. Full- or half-page photos which were in the middle of the booklet are now placed at the end. This is not meant as an academic work, so if anyone reads a statement which they believe is inaccurate or just plain wrong, the mistake is not mine. -

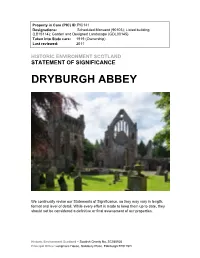

Dryburgh Abbey Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC 141 Designations: Scheduled Monuent (90103); Listed building (LB15114); Garden and Designed Landscape (GDL00145) Taken into State care: 1919 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2011 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE DRYBURGH ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH DRYBURGH ABBEY SYNOPSIS Dryburgh Abbey comprises the ruins of a Premonstratensian abbey, founded in 1150 by Hugh de Morville, constable of Scotland. The upstanding remains incorporate fine architecture from the 12th, 13th and 15th centuries. Following the Protestant Reformation (1560) the abbey passed through several secular hands, until coming into the possession of David Erskine, 11th earl of Buchan, who recreated the ruin as the centrepiece of a splendid Romantic landscape. Buchan, Sir Walter Scott and Field-Marshal Earl Haig are all buried here. While a greater part of the abbey church is now gone, what does remain - principally the two transepts and west front - is of great architectural interest. The cloister buildings, particularly the east range, are among the best preserved in Scotland. The chapter house is important as containing rare evidence for medieval painted decoration. The whole site, tree-clad and nestling in a loop of the River Tweed, is spectacularly beautiful and tranquil. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE COURT OF THE COMMISSARIES OF EDINBURGH: CONSISTORIAL LAW AND LITIGATION, 1559 – 1576 Based on the Surviving Records of the Commissaries of Edinburgh BY THOMAS GREEN B.A., M.Th. I hereby declare that I have composed this thesis, that the work it contains is my own and that this work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification, PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2010 Thy sons, Edina, social, kind, With open arms the stranger hail; Their views enlarg’d, their lib’ral mind, Above the narrow rural vale; Attentive still to sorrow’s wail, Or modest merit’s silent claim: And never may their sources fail! And never envy blot their name! ROBERT BURNS ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines the appointment of the Commissaries of Edinburgh, the court over which they presided, and their consistorial jurisdiction during the era of the Scottish Reformation. -

The Monks of Tiron: a Monastic Community and Religious Reform¨ in the Twelfth Century Kathleen Thompson Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02124-2 - The Monks of Tiron: A Monastic Community and Religious Reform¨ in the Twelfth Century Kathleen Thompson Index More information Index Abbeville, 97 attitude to wealth, 21 Ablis, priory, 134 , 138 , 140 biblical imagery, 122 Achery, Luc d’, 36 , 40 canonisation dossier, 60 Adam de Port, 79 , 81 death, 121 Adam of Perseigne, 184 early life, 97 Adela, countess of Blois and Chartres, 95 , evolution of narrative of his life, 32 131 , 136 , 139 lion imagery, 107 Adelaide, countess of Blois and Chartres, manual labour, 21 , 111 181 , 192 memory of, 122 , 164 Adjutor, vita , 40 , 241 monastic rule, 110 Agnes of Montigny-le-Gannelon, 114 , 133 mortuary roll, 32 , 122 Alan, son of Jordan, steward of Dol, 169 portrait, 114 Alexander III, pope, 74 , 83 , 89 , 175 preaching, 22 , 59 , 103 , 123 Algar, bishop of Coutances, 170 refectorian, 26 Anasthasius of Venice, 44 reputation, 121 Andrew of Baudemont, 139 sermon at Coutances, 22 , 27 , 124 Andrew of Fontevraud, 15 , 39 settles in diocese of Chartres, 103 Andrew, abbot of St Dogmael’s, 85 sources for his life, 12 Andwell, priory, see Mapledurwell, priory support for the poor, 21 Anjou, counts of, 159 wandering preacher, 30 , 59 apostolic life, 139 wilderness, 20 , 24 , 61 Arbroath, abbey, 87 , 89 , 176 Bernard, bishop of St David’s, 85 , 115 Arcisses, 24 , 50 , 104 Bernold of Constance, 138 Arcisses, abbey, 186 Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS armarius , 72 , 164 Latin, 40 Asnières, abbey, 93 , 130 , 144 , 149 , 197 Billaine, Jean, 36 Audita, obedientia