Man in Moray

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

126613853.23.Pdf

Sc&- PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME LIV STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH OCTOBEK 190' V STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH 1225-1559 Being a Translation of CONCILIA SCOTIAE: ECCLESIAE SCOTI- CANAE STATUTA TAM PROVINCIALIA QUAM SYNODALIA QUAE SUPERSUNT With Introduction and Notes by DAVID PATRICK, LL.D. Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1907 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION— i. The Celtic Church in Scotland superseded by the Church of the Roman Obedience, . ix ir. The Independence of the Scottish Church and the Institution of the Provincial Council, . xxx in. Enormia, . xlvii iv. Sources of the Statutes, . li v. The Statutes and the Courts, .... Ivii vi. The Significance of the Statutes, ... lx vii. Irreverence and Shortcomings, .... Ixiv vni. Warying, . Ixx ix. Defective Learning, . Ixxv x. De Concubinariis, Ixxxvii xi. A Catholic Rebellion, ..... xciv xn. Pre-Reformation Puritanism, . xcvii xiii. Unpublished Documents of Archbishop Schevez, cvii xiv. Envoy, cxi List of Bishops and Archbishops, . cxiii Table of Money Values, cxiv Bull of Pope Honorius hi., ...... 1 Letter of the Conservator, ...... 1 Procedure, ......... 2 Forms of Excommunication, 3 General or Provincial Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 8 Aberdeen Synodal Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 30 Ecclesiastical Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, . 46 Constitutions of Bishop David of St. Andrews, . 57 St. Andrews Synodal Statutes of the Fourteenth Century, vii 68 viii STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH Provincial and Synodal Statute of the Fifteenth Century, . .78 Provincial Synod and General Council of 1420, . 80 General Council of 1459, 82 Provincial Council of 1549, ...... 84 General Provincial Council of 1551-2 ... -

ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH - HOUSING ORDERS PUBLIC REGISTER As Of: 01 October 2020

ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH - HOUSING ORDERS PUBLIC REGISTER as of: 01 October 2020 Closing Order Property Reference:Address of Property: Date Served: Demolished, Revoked or Withdrawn 72/00014/RES73 Main Street Newmill Keith Moray AB55 6TS 04 August 1972 77/00012/RES3 Great Western Road Buckie Moray AB56 1XX 26 June 1977 76/00001/RESNetherton Farm Cottage Forres Moray IV36 3TN 07 November 1977 81/00008/RES12 Seatown Lossiemouth Moray IV31 6JJ 09 December 1981 80/00007/RESBroadrashes Newmill Keith Moray AB55 6XE 29 November 1989 89/00003/RES89 Regent Street Keith Moray AB55 5ED 29 November 1989 93/00001/RES4 The Square Archiestown Aberlour Moray AB38 7QX 05 October 1993 94/00006/RESGreshop Cottage Forres Moray IV36 2SN 13 July 1994 94/00005/RESHalf Acre Kinloss Forres Moray IV36 2UD 24 August 1994 20/00005/RES2 Pretoria Cottage Balloch Road Keith Moray 30 May 1995 95/00001/RESCraigellachie 4 Burdshaugh Forres Moray IV36 1NQ 31 October 1995 78/00008/RESSwiss Cottage Fochabers Moray IV32 7PG 12 September 1996 99/00003/RES6 Victoria Street Craigellachie Aberlour Moray AB38 9SR 08 November 1999 01 October 2020 Page 1 of 14 ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH - HOUSING ORDERS PUBLIC REGISTER as of: 01 October 2020 Closing Order Property Reference:Address of Property: Date Served: Demolished, Revoked or Withdrawn 01/00001/RESPittyvaich Farmhouse Dufftown Keith Moray AB55 4BR 07 November 2001 03/00004/RES113B Mid Street Keith Moray AB55 5AE 01 April 2003 05/00001/RESFirst Floor Flat 184 High Street Elgin Moray IV30 1BA 18 May 2005 03 September 2019 05/00002/RESSecond -

FINALISED Area Profile 2015

Duffus, Moray Area profile Duffus (Scottish Gaelic: Dubhais) is a village in Moray to the north-west of Elgin. The Duffus name has undergone a variety of spelling changes through the years; in 1290, "Dufhus", and in 1512, "Duffous". The name is possibly a compilation of two Gaelic words, dubh and uisg, meaning "darkwater" or "blackwater". The current village is a grid plan village established as a planned settlement in 1811, replacing an earlier medieval settlement which lay 0.25 miles to the east, of which only the ruined Old Parish Church remains. Nearby are the remains of Duffus Castle, St. Peters' Kirk, and Spynie Palace. © Crown Copyright 2016 Also nearby is Gordonstoun School which is a co-educational independent (public) school where three generations of British royalty have been educated including the Duke of Edinburgh and the Prince of Wales. Corporate Policy Unit The Moray Council October 2016 1 /33 Table of Contents 1 Population Structure ..................................................................................... 4 1.1 Age profile ............................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Marital Status ........................................................................................................ 6 2 Identity............................................................................................................ 7 2.1 Ethnicity ................................................................................................................ 7 2.2 -

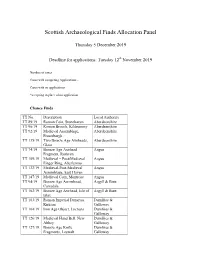

Scottish Archaeological Finds Allocation Panel

Scottish Archaeological Finds Allocation Panel Thursday 5 December 2019 Deadline for applications: Tuesday 12th November 2019 Number of cases – Cases with competing Applications - Cases with no applications – *accepting in place of no application Chance Finds TT No. Description Local Authority TT 89/19 Roman Coin, Stonehaven Aberdeenshire TT 90/19 Roman Brooch, Kildrummy Aberdeenshire TT 92/19 Medieval Assemblage, Aberdeenshire Fraserburgh TT 135/19 Two Bronze Age Axeheads, Aberdeenshire Glass TT 74/19 Bronze Age Axehead Angus Fragment, Ruthven TT 109/19 Medieval – Post-Medieval Angus Finger Ring, Aberlemno TT 132/19 Medieval-Post-Medieval Angus Assemblage, East Haven TT 147/19 Medieval Coin, Montrose Angus TT 94/19 Bronze Age Arrowhead, Argyll & Bute Carradale TT 102/19 Bronze Age Axehead, Isle of Argyll & Bute Islay TT 103/19 Roman Imperial Denarius, Dumfries & Kirkton Galloway TT 104/19 Iron Age Object, Lochans Dumfries & Galloway TT 126/19 Medieval Hand Bell, New Dumfries & Abbey Galloway TT 127/19 Bronze Age Knife Dumfries & Fragments, Leswalt Galloway TT 146/19 Iron Age/Roman Brooch, Falkirk Stenhousemuir TT 79/19 Medieval Mount, Newburgh Fife TT 81/19 Late Bronze Age Socketed Fife Gouge, Aberdour TT 99/19 Early Medieval Coin, Fife Lindores TT 100/19 Medieval Harness Pendant, Fife St Andrews TT 101/19 Late Medieval/Post-Medieval Fife Seal Matrix, St Andrews TT 111/19 Iron Age Button and Loop Fife Fastener, Kingsbarns TT 128/19 Bronze Age Spearhead Fife Fragment, Lindores TT 112/19 Medieval Harness Pendant, Highland Muir of Ord TT -

February Magazine Web

Rector Rev Kirstin Freeman February 2020 Magazine E-mail [email protected] Other contacts can be found on the printed copy in the church Web Site: http://bearsden.church.scot Web Site Co-ordinator: Janet Stack ([email protected]) All Saints is a registered charity in Scotland SCO005552 Cover picture : Rt Revd Kevin Pearson our bishop-elect All Saints Scottish Episcopal Church Drymen Road, Bearsden £1 A new bishop for the Diocese already know many in the Diocese but are also looking forward to living there and getting to know the people and the area better. We shall be very sad to be leaving The Right Reverend Kevin Pearson was elected as the new Bishop of Glasgow and the people of Argyll and The Isles which we have grown to love deeply over nine Galloway, on Saturday 18 th January. Bishop Kevin is currently the Bishop of Argyll years of ministry there.” and The Isles and his election to Glasgow and Galloway represents a historic Bishop Kevin is married to Dr Elspeth Atkinson who is Chief Operating Officer for the “translation” of a Bishop from one See to another. Bishop Kevin will take up his new Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St Andrews & Edinburgh. Prior to that Elspeth was post at a service of installation later in the year, on a date to be announced in due Director of MacMillan Cancer Support in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales and course. for most of her career held senior roles in Economic Development in Scotland. Bishop Kevin has served as Bishop of Argyll and The Isles since February 2011 and before that was Rector of St Michael & All Saints Church in Edinburgh, Canon of St Requiem a nd Service of Dedication Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh, Dean of the Diocese of Edinburgh and the Provincial Director of Ordinands. -

Site Summary

Dynamic Coast Scotland’s National Coastal Change Assessment Dynamic Coast – Scotland’s National Coastal Change Assessment Site Summary Culbin (including Nairn) (Site 33) 0 Dynamic Coast Scotland’s National Coastal Change Assessment Disclaimer The evidence presented within the National Coastal Change Assessment (NCCA) must not be used for property level of scale investigations. Given the precision of the underlying data (including house location and roads etc.) the NCCA cannot be used to infer precise extents or timings of future erosion. The likelihood of erosion occurring is difficult to predict given the probabilistic nature of storm events and their impact. The average erosion rates used in NCCA contain very slow periods of limited change followed by large adjustments during storms. Together with other local uncertainties, not captured by the national level data used in NCCA, detailed local assessments are unreliable unless supported by supplementary detailed investigations. The NCCA has used broad patterns to infer indicative regional and national level assessments to inform policy and guide follow-up investigations. Use of these data beyond national or regional levels is not advised and the Scottish Government cannot be held responsible for misuse of the data. Culbin (including Nairn) (Site 33) Historic Change: The beaches and sand dunes at Culbin stretch between the mouth of the River Findhorn and Nairn, its inland dunes and beach ridges covering an area of 5,000 hectares. Whilst much of the dunes were stabilised after the First World War and now contain extensive pine plantations, the beaches are some of the most spectacular in Scotland and are our most dynamic beaches. -

Littlehaugh Cottage, Glen of Rothes, Aberlour, Moray

LITTLEHAUGH COTTAGE, GLEN OF ROTHES, ABERLOUR, MORAY LITTLEHAUGH COTTAGE, GLEN OF ROTHES, ABERLOUR, MORAY Two cottages built in the 1927 converted into one spacious home situated between Elgin and the village of Rothes. Description A96(T) road enabling Inverness and Aberdeen Airports General Information Littlehaugh Cottage is a charming 4 bedroom single to be reached within one and 1¼ hours respectively storey dwelling with slate roof. The property is traffic permitting. There are railway stations at Elgin, Services surrounded by a good sized garden and grounds of Aviemore (30 minutes), Inverness and Aberdeen. Mains water and electricity, private drainage and oil fired about 0.30 Ha (0.74 acres) and has good views to the central heating. east. It benefits from pvc double glazing and oil fired The Spey Valley is renowned for its excellent salmon central heating. fishing on the River Spey with the Rothes, Delfur and Rights of Way, Easements & Wayleaves Arndilly beats all within close proximity. The area also The access between the public road and the cottage is Situation abounds with golf courses and sandy beaches along included in the sale as shown on the plan. The small town of Rothes about 1½ miles to the the Moray coast. There are other opportunities for south provides basic daily requirements including two leisure activities such as mountaineering, skiing and Local Authority convenience stores, a butcher, chemist, library, post mountain biking in the nearby Cairngorm National Park. office, hotels and medical centre. Aberlour, about The Moray Council, Council Office 5 miles to the south has a supermarket, banks, a good Accommodation High Street, Elgin, Moray IV30 1BX range of shops, leisure facilities, doctor’s surgery and Littlehaugh Cottage is situated adjacent to the A941 Tel: 01343 543451 www.moray.gov.uk Speyside High School. -

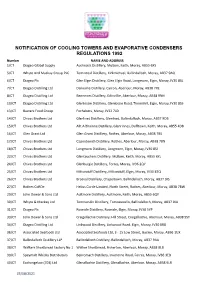

Cooling Tower Register

NOTIFICATION OF COOLING TOWERS AND EVAPORATIVE CONDENSERS REGULATIONS 1992 Number NAME AND ADDRESS 1/CTDiageo Global Supply Auchroisk Distillery, Mulben, Keith, Moray, AB55 6XS 5/CTWhyte And Mackay Group PLC Tomintoul Distillery, Kirkmichael, Ballindalloch, Moray, AB37 9AQ 6/CTDiageo Plc Glen Elgin Distillery, Glen Elgin Road, Longmorn, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8SL 7/CTDiageo Distilling Ltd Dailuaine Distillery, Carron, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7RE 8/CTDiageo Distilling Ltd Benrinnes Distillery, Edinvillie, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 9NN 10/CTDiageo Distilling Ltd Glenlossie Distillery, Glenlossie Road, Thomshill, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8SS 13/CTBaxters Food Group Fochabers, Moray, IV32 7LD 14/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Glenlivet Distillery, Glenlivet, Ballindalloch, Moray, AB37 9DB 15/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Allt A Bhainne Distillery, Glenrinnes, Dufftown, Keith, Moray, AB55 4DB 16/CTGlen Grant Ltd Glen Grant Distillery, Rothes, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7BS 17/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Caperdonich Distillery, Rothes, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7BN 18/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Longmorn Distillery, Longmorn, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8SJ 22/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Glentauchers Distillery, Mulben, Keith, Moray, AB55 6YL 24/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Glenburgie Distillery, Forres, Moray, IV36 2QY 25/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Miltonduff Distillery, Miltonduff, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8TQ 26/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Braeval Distillery, Chapeltown, Ballindalloch, Moray, AB37 9JS 27/CTRothes CoRDe Helius Corde Limited, North Street, Rothes, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7BW 29/CTJohn Dewar & Sons Ltd Aultmore Distillery, -

St John the Evangelist Scottish Episcopal Church

St John the Evangelist Scottish Episcopal Church Forres General Data Protection Compliance Statement St John’s Forres is an incumbency within the Scottish Episcopal Church. It is established exclusively for charitable purposes, primarily for the advancement of religion and to provide public benefit. (The expression “charitable purposes” shall mean a charitable purpose as defined in section 7 of the Charities and Trustee Investment (Scotland) Act 2005 as amended from time to time (“the 2005 Act”) which is also regarded as a charitable purpose in relation to the application of the Taxes Acts from time to time in force.) In order to progress its charitable purposes, the Clergy and Vestry of St John’s Forres collects and processes information from congregation members on the legal basis of informed consent. This information supports the following activities: 1. Pastoral care for the congregation 2. Financial security for the incumbency, its employees and its assets 3. Charitable giving 4. Communication with congregation members about the worship pattern and other activities of the church. 5. Enabling St John’s to provide a voluntary service for the benefit of the wider community. Vestry is responsible for the privacy, security, retention of this information within legal limits, and destruction/deletion of the same when appropriate. It undertakes to audit this information and to assess for risk on an annual basis, to enable subject access appropriately if so requested, and to ensure that congregation members are made aware of exactly what use is intended from the information which is requested and processed. Sharing of your data Your personal data is confidential and will be shared only as set out here. -

Of 5 Polling District Polling District Name Polling Place Polling Place Local Government Ward Scottish Parliamentary Cons

Polling Polling District Local Government Scottish Parliamentary Polling Place Polling Place District Name Ward Constituency Houldsworth Institute, MM0101 Dallas Houldsworth Institute 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Dallas, Forres, IV36 2SA Grant Community Centre, MM0102 Rothes Grant Community Centre 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray 46 - 48 New Street, Rothes, AB38 7BJ Boharm Village Hall, MM0103 Boharm Boharm Village Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Mulben, Keith, AB56 6YH Margach Hall, MM0104 Knockando Margach Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Knockando, Aberlour, AB38 7RX Archiestown Hall, MM0105 Archiestown Archiestown Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray The Square, Archiestown, AB38 7QX Craigellachie Village Hall, MM0106 Craigellachie Craigellachie Village Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray John Street, Craigellachie, AB38 9SW Drummuir Village Hall, MM0107 Drummuir Drummuir Village Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Drummuir, Keith, AB55 5JE Fleming Hall, MM0108 Aberlour Fleming Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Queens Road, Aberlour, AB38 9PR Mortlach Memorial Hall, MM0109 Dufftown & Cabrach Mortlach Memorial Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Albert Place, Dufftown, AB55 4AY Glenlivet Public Hall, MM0110 Glenlivet Glenlivet Public Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Glenlivet, Ballindalloch, AB37 9EJ Richmond Memorial Hall, MM0111 Tomintoul Richmond Memorial Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Tomnabat Lane, Tomintoul, Ballindalloch, AB37 9EZ McBoyle Hall, BM0201 Portknockie McBoyle Hall 2 - Keith and Cullen Banffshire and Buchan Coast Seafield -

List of Public Roads

Moray Council Environmental & Commercial Services Roads Maintenance List of Public Roads Lengths (Km) Road No / Carriageway Footway / Cycleway / Burgh Road / Street Name Road / Street Description Footpath CycleTrack Overall Summary of All Classifications A Class Roads 157.291 38.184 3.110 B Class Roads 296.332 36.699 3.220 C Class Roads 365.732 45.708 4.753 Unclassified Roads 738.519 404.666 10.064 Total 1,557.874 525.257 21.147 Remote Footpaths 0.000 19.874 0.000 Remote Cycle Tracks 0.000 0.000 34.990 Total 0.000 19.874 34.990 Date Printed - 24/08/2021 Page 1 of 130 Moray Council Environmental & Commercial Services Roads Maintenance List of Public Roads Lengths (Km) Road No / Carriageway Footway / Cycleway / Burgh Road / Street Name Road / Street Description Footpath CycleTrack A Class Roads A95 Keith - Glenbarry Road From Trunk Road A96 (Church Road) in Keith to Council 14.180 1.099 0.000 Boundary at Glenbarry A97 Banff - Aberchirder - Huntly Portion of Road from Bridge of Marnoch to Council 0.753 0.000 0.000 Road Boundary at Auchingoul A98 Fochabers - Cullen - From A96 at Fochabers (Main Road), via Arradoul (Main 20.911 5.282 0.000 Fraserburgh Road Road) then Cullen (Castle Terrace, Bayview Road, Seafield Street, Seafield Road) thence to Council Boundary at Tochieneal, east of Cullen. A920 Dufftown - Huntly Road From junction with Route A941 at Burnend via 6.097 0.000 0.000 Auchindoun to Council Boundary at Corsemaul. A939 Nairn - Tomintoul - Ballater Road From Council Boundary at Bridge of Brown via 18.060 1.328 0.000 Tomintoul (Main Street and Auchbreck Road) and Blairmarrow to Council Boundary at Lecht Hill. -

Ronnie's Cabs

transport guide FOREWORD The Moray Forum is a constituted voluntary organisation that was established to provide a direct link between the Area Forums and the Moray Community Planning Partnership. The Forum is made up of two representatives of each of the Area Forums and meets on a regular basis. Further information about The Moray Forum is available on: www.yourmoray.org.uk Area Forums are recognised by the Moray Community Planning Partnership as an important means of engaging local people in the Community Planning process. In rural areas - such as Moray - transport is a major consideration, so in September 2011 the Moray Forum held its first transport seminar to look at the issues and concerns that affect our local communities in respect of access to transport. Two actions that came from that event was the establishment of a Passenger Forum and a Transport Providers Network. This work was taken forward by the Moray Forum Transport Working Group made up of representatives of the Area Forums, Moray Council, NHS Grampian, tsiMORAY, and community transport schemes. In September 2013 the Working Group repeated the seminar to see how much progress had been made on the actions and issues identified in 2011. As a direct result of the work of the Group this Directory has been produced in order to address an on-going concern that has been expressed of the lack of information on what transport is available in Moray, the criteria for accessing certain transport services, and where to go for further advice. The Moray Forum Transport Working Group would like to acknowledge the help of all the people who provided information for this Directory, and thereby made a contribution towards the integration of public, private and community transport services within Moray.