This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate's Close Proximity to The

Edinburgh Graveyards Project: Documentary Survey For Canongate Kirkyard --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate’s close proximity to the Palace of Holyroodhouse, which is situated at the eastern end of Canongate Burgh, has been influential on both the fortunes of the Burgh and the establishment of Canongate Kirk. In 1687, King James VII declared that the Abbey Church of Holyroodhouse was to be used as the chapel for the re-established Order of the Thistle and for the performance of Catholic rites when the Royal Court was in residence at Holyrood. The nave of this chapel had been used by the Burgh of Canongate as a place of Protestant worship since the Reformation in the mid sixteenth century, but with the removal of access to the Abbey Church to practise their faith, the parishioners of Canongate were forced to find an alternative venue in which to worship. Fortunately, some 40 years before this edict by James VII, funds had been bequeathed to the inhabitants of Canongate to erect a church in the Burgh - and these funds had never been spent. This money was therefore used to build Canongate Kirk and a Kirkyard was laid out within its grounds shortly after building work commenced in 1688. 1 Development It has been ruminated whether interments may have occurred on this site before the construction of the Kirk or the landscaping of the Kirkyard2 as all burial rights within the church had been removed from the parishioners of the Canongate in the 1670s, when the Abbey Church had became the chapel of the King.3 The earliest known plan of the Kirkyard dates to 1765 (Figure 1), and depicts a rectilinear area on the northern side of Canongate burgh with arboreal planting 1 John Gifford et al., Edinburgh, The Buildings of Scotland: Pevsner Architectural Guides (London : Penguin, 1991). -

Bygone Church Life in Scotland

*«/ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA GIFT OF Old Authors Farm Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/bygonechurchlifeOOandrrich law*""^""*"'" '* BYGONE CHURCH LIFE IN SCOTLAND. 1 f : SS^gone Cburcb Xife in Scotland) Milltam Hnbrewa . LONDON WILLIAM ANDREWS & CO., 5. FARRINGDON AVENUE, E.G. 1899. GIFT Gl f\S2S' IPreface. T HOPE the present collection of new studies -*- on old themes will win a welcome from Scotsmen at home and abroad. My contributors, who have kindly furnished me with articles, are recognized authorities on the subjects they have written about, and I think their efforts cannot fail to find favour with the reader. V William Andrews. The HuLl Press, Christmas Eve^ i8g8. 595 Contents. PAGE The Cross in Scotland. By the Rev. Geo. S. Tyack, b.a. i Bell Lore. By England Hewlett 34 Saints and Holy Wells. By Thomas Frost ... 46 Life in the Pre-Reformation Cathedrals. By A. H. Millar, F.S.A., Scot 64 Public Worship in Olden Times. By the Rev. Alexander Waters, m.a,, b.d 86 Church Music. By Thomas Frost 98 Discipline in the Kirk. By the Rev. Geo. S. Tyack, b.a. 108 Curiosities of Church Finance. By the Rev. R. Wilkins Rees 130 Witchcraft and the Kirk. By the Rev. R. Wilkins Rees 162 Birth and Baptisms, Customs and Superstitions . 194 Marriage Laws and Customs 210 Gretna Green Gossip 227 Death and Burial Customs and Superstitions . 237 The Story of a Stool 255 The Martyrs' Monument, Edinburgh .... 260 2 BYGONE CHURCH LIFE. -

Historyofscotlan10tytliala.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook Illustrations of Edinburgh and other material collected by Sir Daniel Wilson, some of which he used in his Memorials of Edinburgh in the olden time (Edin., 1847). The following list gives possible sources for the items; some prints were published individually as well as appearing as part of larger works. References are also given to their use in Memorials. Quick-links within this list: Box I Box II Box III Abbreviations and notes Arnot: Hugo Arnot, The History of Edinburgh (1788). Bann. Club: Bannatyne Club. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated: W. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated in a series of views [ca. 1840]. Beauties of Scotland: R. Forsyth, The Beauties of Scotland (1805-8). Billings: R.W. Billings, The Baronial and ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland (1845-52). Black (1843): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1843). Black (1859): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1859). Edinburgh and Mid-Lothian (1838). Drawings by W.B. Scott, engraved by R. Scott. Some of the engravings are dated 1839. Edinburgh delineated (1832). Engravings by W.H. Lizars, mostly after drawings by J. Ewbank. They are in two series, each containing 25 numbered prints. See also Picturesque Views. Geikie, Etchings: Walter Geikie, Etchings illustrative of Scottish character and scenery, new edn [1842?]. Gibson, Select Views: Patrick Gibson, Select Views in Edinburgh (1818). Grose, Antiquities: Francis Grose, The Antiquities of Scotland (1797). Hearne, Antiquities: T. Hearne, Antiquities of Great Britain illustrated in views of monasteries, castles and churches now existing (1807). Heriot’s Hospital: Historical and descriptive account of George Heriot’s Hospital. With engravings by J. -

Appendix 2 OLD TOWN DRAFT CONSERVATION AREA

Appendix 2 OLD TOWN DRAFT CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL LOCATION AND BOUNDARIES The Old Town is an easily recognised entity within the wider city boundaries, formed along the spine of the hill which tails down from the steep Castle rock outcrop and terminates at the Palace of Holyroodhouse. It has naturally defined boundaries to the north, where the valley contained the old Nor’ Loch, and on the south the corresponding parallel valley of the Cowgate. The northern and western boundaries of the Conservation Area are well defined by the Castle and Princes Street Gardens, and to the east by Calton Hill and Calton Road. Arthur’s Seat, to the southeast, is a dominating feature which clearly defines the edge of the Conservation Area. DATES OF DESIGNATION/AMENDMENTS The Old Town Conservation Area was designated in July 1977 with amendments in 1982, 1986 and 1996. An Article 4 Direction Order which restricts normally permitted development rights was first made in 1984. WORLD HERITAGE STATUS The Old Town Conservation Area forms part of the Old and New Towns of Edinburgh World Heritage Site which was inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage Site list in 1995. This was in recognition of the outstanding architectural, historical and cultural importance of the Old and New Towns of Edinburgh. Inscription as a World Heritage Site brings no additional statutory powers. However, in terms of UNESCO’s criteria, the conservation and protection of the World Heritage Site are paramount issues. Inscription commits all those involved with the development and management of the Site to ensure measures are taken to protect and enhance the area for future generations. -

The West Front of Holyrood Abbey J Philip Mcaleer*

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 115 (1985), 263-275 A unique facade in Great Britain: the west front of Holyrood Abbey J Philip McAleer* SUMMARY The early Gothic facade of Holyrood Abbey was originally distinguished by two large towers. Although many large churches British builtthe in Isles during previousthe (12th) centurytwo had western towers, they were generally built over the westernmost bays of the nave aisles. In the case of a buildingsfew datinglaterthe to 12th earlyand 13th centuries, towersthe flanked lastthe baysthe of aisles, thereby creating widea 'screen' fagade. position towersThe the Holyroodof at distinctlywas different from either of these types. The towers were placed both outside the line of the aisle walls and in westplanefrontthe the of wall:of they were tangent corners aislesthe theirthe of to onlyof by one corners. As a result, a shallow open space was created between them, in front of the west portal. In this regard, Holyrood appears haveto been exceptional Britishthe in Isles. closestThe parallels thisfor arrangement are found at several churches on the Continent which are widely separated geographically group,and,a as without obviousany connection with each other. unusualThe system of passageways within westthe front Holyroodof also further contributes uniqueits to character. Althoug facade Augustiniae hth th f eo n abbey churc Holyroodf ho , Canongate, Edinburghs i , longeo n r complete, what does remai morf o s ni e than routine interest suggestt i r ,fo mossa t unusual arrangement facade 1.Th e stands adjacen muce th o ht later Palac Holyroodhousf eo e and, indeeds it , integrity was severely compromised by the construction of the existing north range of the Palace. -

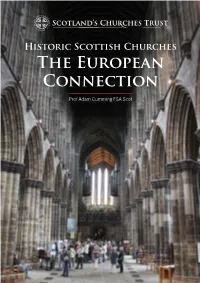

The European Connection

Historic Scottish Churches The European Connection Prof Adam Cumming FSA Scot Adam Cumming Talk “It is often assumed that Scotland took its architectural lead from England, but this is not completely true, Scotland had its own links across Europe, and these developed and changed with time.” cotland has many medieval Glasgow Cathedral which can be churches though not all are shown to have architectural links well known. They deserve across Europe. Sgreater awareness. Many The early Scottish church, that of are ruined but many are not, and Ninian and Columba (as well as many others often survive in some form in others), was part of the early church adapted buildings. before the great schism 1054. It was It is often assumed that Scotland organised a little like the Orthodox took its architectural lead from Churches now. The church below is England, but this is not completely that of Rila Monastery in Bulgaria, an true, Scotland had its own links Orthodox community and similar in across Europe, and these developed plan to early Scottish ones with the and changed with time. The changes church in the centre of the complex. were usually a response to politics It is often described as Celtic and trade. This is of course reflected which is a later description but does in the buildings across Scotland. emphasise a common base with It can be argued that these form a Ireland and Wales etc. There was distinctive part of European culture a great deal of movement across with regional variations. Right is northern Europe and it retained close links with Ireland and elsewhere via ‘Schottenkloster’ and other mission centres. -

The Fourth Earl of Cassillis in 1576

Brennan, Brian (2019) A history of the Kennedy Earls of Cassillis before 1576. PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/70978/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A History of the Kennedy Earls of Cassillis before 1576 Brian Brennan BSc MA MLitt Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Arts) School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow Abstract This thesis will study the Kennedy family, beginning with its origins as a minor cadet branch of the lineage that ruled Galloway in the twelfth century, and trace its history until the death of the fourth earl of Cassillis in 1576. A study of how the Kennedys extended their influence across south-west Scotland and acquired an earldom has never been undertaken. This thesis aims to fill the significant gap in our understanding of how lordship operated in this region. In particular, analysis of the interactions between the Kennedys and the earls of Carrick, usually the monarch or his heir, demonstrates that the key factor in their success was their policy of close alignment and support of the crown. -

THE SUCCESSION and FOREIGN POLICY , By: Adams, Simon, History Today, 00182753, May2003, Vol

Title: THE SUCCESSION AND FOREIGN POLICY , By: Adams, Simon, History Today, 00182753, May2003, Vol. 53, Issue 5 THE SUCCESSION AND FOREIGN POLICY Simon Adams looks at the close connections between Elizabeth's ascendancy, her religion and her ensuing, relationships with the states of Europe. 'She is a very prudent and accomplished princess, who has been well educated, she plays all sorts of instruments and speaks several languages (even Latin) extremely well. Good-natured and quick spirited, she is a woman who loves justice greatly and does not impose on her subjects. She was good-looking in her youth, but she is also tight-fisted to the point of avarice, easily angered and above all very jealous of her sovereignty.' THIS ASSESSMENT OF Elizabeth I was made in the introductory discourse to his collected papers by Guillaume de d'Aubespine, Baron de Châteauneuf, ambassador from Henry III of France between 1585 and 1590. Given that Châteauneuf's embassy had involved him in the diplomatic nightmare of the trial and execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, it was a remarkably charitable description. But it was not untypical of the respect and even admiration in which Elizabeth was held by French ambassadors to her court. Thanks to the agreement to exchange resident ambassadors that Henry VIII and Francis I made in the Treaty of London of October 1518, the French crown maintained the only permanent embassy of Elizabeth's reign. Unfortunately, accidents of archival survival have left large gaps in the French ambassadorial correspondence and only a small amount has been published. By contrast the Spanish ambassadorial correspondence of the reign was published in full over a century ago, first in Spanish and then in English. -

The Edinburgh Graveyards Project

The Edinburgh Graveyards Project A scoping study to identify strategic priorities for the future care and enjoyment of five historic burial grounds in the heart of the Edinburgh World Heritage Site The Edinburgh Graveyards Project A scoping study to identify strategic priorities for the future care and enjoyment of ve historic burial grounds in the heart of the Edinburgh World Heritage Site Greyfriar’s Kirkyard, Monument No.22 George Foulis of Ravelston and Jonet Bannatyne (c.1633) Report Author DR SUSAN BUCKHAM Other Contributors THOMAS ASHLEY DR JONATHAN FOYLE KIRSTEN MCKEE DOROTHY MARSH ADAM WILKINSON Project Manager DAVID GUNDRY February 2013 1 Acknowledgements his project, and World Monuments Fund’s contribution to it, was made possi- ble as a result of a grant from The Paul Mellon Estate. This was supplemented Tby additional funding and gifts in kind from Edinburgh World Heritage Trust. The scoping study was led by Dr Susan Buckham of Kirkyard Consulting, a spe- cialist with over 15 years experience in graveyard research and conservation. Kirsten Carter McKee, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Architecture at Edinburgh University researching the cultural, political, and social signicance of Calton Hill, undertook the desktop survey and contributed to the Greyfriars exit poll data col- lection. Thomas Ashley, a doctoral candidate at Yale University, was awarded the Edinburgh Graveyard Scholarship 2011 by World Monuments Fund. This discrete project ran between July and September 2011 and was supervised by Kirsten Carter McKee. Special thanks also go to the community members and Kirk Session Elders who gave their time and knowledge so generously and to project volunteers David Fid- dimore, Bob Reinhardt and Tan Yuk Hong Ian. -

The Hannay Family by Col. William Vanderpoel Hannay

THE HANNAY FAMILY BY COL. WILLIAM VANDERPOEL HANNAY AUS-RET LIFE MEMBER CLAN HANNAY SOCIETY AND MEMBER OF THE CLAN COUNCIL FOUNDER AND PAST PRESIDENT OF DUTCH SETTLERS SOCIETY OF ALBANY ALBANY COUNTY HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COPYRIGHT, 1969, BY COL. WILLIAM VANDERPOEL HANNAY PORTIONS OF THIS WORK MAY BE REPRODUCED UPON REQUEST COMPILER OF THE BABCOCK FAMILY THE BURDICK FAMILY THE CRUICKSHANK FAMILY GENEALOGY OF THE HANNAY FAMILY THE JAYCOX FAMILY THE LA PAUGH FAMILY THE VANDERPOEL FAMILY THE VAN SLYCK FAMILY THE VANWIE FAMILY THE WELCH FAMILY THE WILSEY FAMILY THE JUDGE BRINKMAN PAPERS 3 PREFACE This record of the Hannay Family is a continuance and updating of my first book "Genealogy of the Hannay Family" published in 1913 as a youth of 17. It represents an intensive study, interrupted by World Wars I and II and now since my retirement from the Army, it has been full time. In my first book there were three points of dispair, all of which have now been resolved. (I) The name of the vessel in which Andrew Hannay came to America. (2) Locating the de scendants of the first son James and (3) The names of Andrew's forbears. It contained a record of Andrew Hannay and his de scendants, and information on the various branches in Scotland as found in the publications of the "Scottish Records Society", "Whose Who", "Burk's" and other authorities such as could be located in various libraries. Also brief records of several families of the name that we could not at that time identify. Since then there have been published two books on the family. -

Holyrood Abbey Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC223 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13031) Taken into State care: 1906 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE HOLYROOD ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HOLYROOD ABBEY SYNOPSIS The Augustinian Abbey of Holyrood was founded by David I in 1128 as a daughter-house of Merton Priory (Surrey). By the 15th century the abbey was increasingly being used as a royal residence – James II was born there in 1430 - and by the time of the Protestant Reformation (1560) much of the monastic precinct had been subsumed into the embryonic Palace of Holyroodhouse.