The West Front of Holyrood Abbey J Philip Mcaleer*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bygone Church Life in Scotland

*«/ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA GIFT OF Old Authors Farm Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/bygonechurchlifeOOandrrich law*""^""*"'" '* BYGONE CHURCH LIFE IN SCOTLAND. 1 f : SS^gone Cburcb Xife in Scotland) Milltam Hnbrewa . LONDON WILLIAM ANDREWS & CO., 5. FARRINGDON AVENUE, E.G. 1899. GIFT Gl f\S2S' IPreface. T HOPE the present collection of new studies -*- on old themes will win a welcome from Scotsmen at home and abroad. My contributors, who have kindly furnished me with articles, are recognized authorities on the subjects they have written about, and I think their efforts cannot fail to find favour with the reader. V William Andrews. The HuLl Press, Christmas Eve^ i8g8. 595 Contents. PAGE The Cross in Scotland. By the Rev. Geo. S. Tyack, b.a. i Bell Lore. By England Hewlett 34 Saints and Holy Wells. By Thomas Frost ... 46 Life in the Pre-Reformation Cathedrals. By A. H. Millar, F.S.A., Scot 64 Public Worship in Olden Times. By the Rev. Alexander Waters, m.a,, b.d 86 Church Music. By Thomas Frost 98 Discipline in the Kirk. By the Rev. Geo. S. Tyack, b.a. 108 Curiosities of Church Finance. By the Rev. R. Wilkins Rees 130 Witchcraft and the Kirk. By the Rev. R. Wilkins Rees 162 Birth and Baptisms, Customs and Superstitions . 194 Marriage Laws and Customs 210 Gretna Green Gossip 227 Death and Burial Customs and Superstitions . 237 The Story of a Stool 255 The Martyrs' Monument, Edinburgh .... 260 2 BYGONE CHURCH LIFE. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE COURT OF THE COMMISSARIES OF EDINBURGH: CONSISTORIAL LAW AND LITIGATION, 1559 – 1576 Based on the Surviving Records of the Commissaries of Edinburgh BY THOMAS GREEN B.A., M.Th. I hereby declare that I have composed this thesis, that the work it contains is my own and that this work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification, PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2010 Thy sons, Edina, social, kind, With open arms the stranger hail; Their views enlarg’d, their lib’ral mind, Above the narrow rural vale; Attentive still to sorrow’s wail, Or modest merit’s silent claim: And never may their sources fail! And never envy blot their name! ROBERT BURNS ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines the appointment of the Commissaries of Edinburgh, the court over which they presided, and their consistorial jurisdiction during the era of the Scottish Reformation. -

1. SCHOOL: Hucknall National Church of England Aided Infant

WORKSOP PRIORY C OF E PRIMARY ACADEMY ADMISSION ARRANGEMENTS 2018/201 9 WORKSOP PRIORY C of E PRIMARY ACADEMY ADMISSION ARRANGEMENTS 2018-2019 Worksop Priory C of E Primary Academy is a member of the Diocese of Southwell & Nottingham Multi Academy Trust, who are the admissions authority for the academy. The published admissions number is 30 children per year. All applications for the Reception year will be ranked in accordance with the admission criteria, as set out below. All children who are allocated a place will be admitted on the first day of the autumn term. Attendance in our Early Years (Foundation 1) at the Academy does not automatically guarantee a Reception (Foundation 2) place. Applications must be made on the Common Application Form. The offer of a place will be made by the Local Authority to all parents on the ‘offer day’ set out in the co-ordinated scheme. The Academy operates a Waiting List for its intake year group in partnership with Nottinghamshire LA. This is kept and prioritised following the oversubscription criteria until the end of the autumn term. Children with a statement of Special Educational Needs or Education Health and Care Plan that names the Academy will be admitted. ADMISSION CRITERIA (in order of priority) 1. Looked after children and previously looked after children. 2. Children whose parents are regular worshipping members of the Church of England in either of the Worksop Priory Congregations, who have attended at least twice a month every month, for a year, immediately prior to the date of application [Priory Church and Clumber]; 3. -

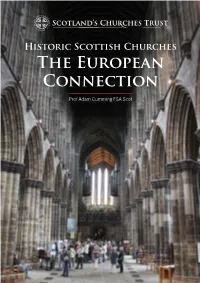

The European Connection

Historic Scottish Churches The European Connection Prof Adam Cumming FSA Scot Adam Cumming Talk “It is often assumed that Scotland took its architectural lead from England, but this is not completely true, Scotland had its own links across Europe, and these developed and changed with time.” cotland has many medieval Glasgow Cathedral which can be churches though not all are shown to have architectural links well known. They deserve across Europe. Sgreater awareness. Many The early Scottish church, that of are ruined but many are not, and Ninian and Columba (as well as many others often survive in some form in others), was part of the early church adapted buildings. before the great schism 1054. It was It is often assumed that Scotland organised a little like the Orthodox took its architectural lead from Churches now. The church below is England, but this is not completely that of Rila Monastery in Bulgaria, an true, Scotland had its own links Orthodox community and similar in across Europe, and these developed plan to early Scottish ones with the and changed with time. The changes church in the centre of the complex. were usually a response to politics It is often described as Celtic and trade. This is of course reflected which is a later description but does in the buildings across Scotland. emphasise a common base with It can be argued that these form a Ireland and Wales etc. There was distinctive part of European culture a great deal of movement across with regional variations. Right is northern Europe and it retained close links with Ireland and elsewhere via ‘Schottenkloster’ and other mission centres. -

Dukeries History Trail Booklet

Key Walk 1 P Parking P W Worksop Café Steetley C P P Meals Worksop W Toilets C Manor P M Museum Hardwick Penny Walk 2 Belph Green Walk 7 W C M P W Toll A60 ClumberC B6034 Bothamsall Creswell Crags M Welbeck P W Walk 6 P W M A614 CWalk 3 P Carburton C P Holbeck P P Norton Walk 4 P A616 Cuckney Thoresby P Hall Budby P W M WalkC 5 Sherwood Forest Warsop Country Park Ollerton The Dukeries History Trail SherwoodForestVisitor.com Sherwood Forest’s amazing north 1. Worksop Priory Worksop is well worth a visit as it has a highly accessible town centre with the Priory, Memorial Gardens, the Chesterfield Canal and the old streets of the Town Centre. Like a lot of small towns, if you look, there is still a lot of charm. Park next to the Priory and follow the Worksop Heritage Trail via Priorswell Road, Potter Street, Westgate, Lead Hill and the castle mound, Newcastle Avenue and Bridge Street. Sit in the Memorial Gardens for a while, before taking a stroll along the canal. Visit Mr Straw’s House(National Trust) BUT you must have pre-booked as so many people want to see it. Welbeck Abbey gates, Sparken Hill to the south of the town. The bridge over the canal with its ‘luxury duckhouse’, Priorswell Road . 2. Worksop Manor Lodge Dating from about 1590, the Lodge is a Grade 1 listed building. Five floors have survived – there were probably another two floors as well so would have been a very tall building for its time. -

Heritage at Risk Priority Sites

Heritage at Risk Priority Sites Contents Page Introduction 2 East Midlands 3 East of England 16 London 27 North East 41 North West 53 South East 64 South West 76 West Midlands 87 Yorkshire and the Humber 99 1 Introduction What are priority Heritage at Risk Sites? Priority Heritage at Risk sites are those sites that English Heritage has identified for additional support to save them for the future. We will be working with owners, developers, trusts and local authorities to find the right solution for these sites with the aim of getting them repaired and back into sustainable use where possible, so they can be removed from the Heritage at Risk Register. Solutions will vary from site to site, possibly with more than one option and so the support that English Heritage will provide is site and option dependent. The different kinds of support could include one or more activities such as expert local advice, partnership working with local authorities, updated information on the significance of the site to aid understanding, and grant aid. For further information or to discuss a site on the priority list contact the relevant English Heritage office. East Midlands Tel: 01604 735400 Email: [email protected] East of England Tel: 01223 582700 Email: [email protected] London Tel: 020 7973 3000 Email: [email protected] North East Tel: 0191 269 1200 Email: [email protected] North West Tel: 0161 242 1400 Email: [email protected] South East Tel: 01483 252000 Email: -

Worksop Priory C of E Primary Academy

Worksop Priory C of E Primary Academy Headteacher: Mr P Abbott MA, BA (Hons), NPQH Holles Street, Worksop, Nottinghamshire, S80 2LJ Telephone: 01909 478886 Website: http://priory-academy.online email: [email protected] Thursday 14th January 2020 Dear Parents and carers, I am writing with details of our finalised remote learning approach for the rest of the half-term. Who should take part in remote learning? The government expects all children to take part in remote learning if they are not in school. With this in mind, alongside teaching children of key workers and vulnerable families in school, staff have produced an outstanding daily suite of learning for each child. Whilst it is highly desirable that children complete all of the work set, we appreciate that this isn’t always going to be possible and would encourage parents and carers to help their children complete as much of the daily work as possible. What consideration has the school given to the style of learning set? We have carefully considered a range of approaches and research around the best forms of home learning. We are applying the following principles to the work we set: We assume that, unless you tell us otherwise, your child has access to the internet Work is set daily in one simple and easy to follow format on the class blog Where possible, teaching is delivered in a video format for children to pause and rewind when required All children have access to a purple book in which to record their work Teaching on the videos is delivered by your child’s class teacher or from other organisations where good videos already exist There are informal opportunities for pupils to talk to their class teacher in the daily TEAMs meetings, and/or via a class email address The curriculum we teach at home is the same as the curriculum being delivered in school Where paper-based resources are requested, they are provided by the school weekly When should my child complete their work? Most of the learning set for each day can be done at any time during the day and in any order. -

CENTENARY INDEX to the TRANSACTIONS of the THOROTON SOCIETY of NOTTINGHAMSHIRE Volumes 1 - 100 1897-1997

CENTENARY INDEX To the TRANSACTIONS OF THE THOROTON SOCIETY of NOTTINGHAMSHIRE Volumes 1 - 100 1897-1997 Together with the THOROTON SOCIETY RECORD SERIES Volumes I - XL 1903-1997 and the THOROTON SOCIETY EXCAVATION SECTION Annual Reports1936-40 Compiled by LAURENCE CRAIK ã COPYRIGHT THOROTON SOCIETY AND COMPILER ISBN 0 902719 19X INTRODUCTION The Thoroton Society began to publish the 'Transactions' in 1897. This volume is intended as an Centenary index to all material published in the 'Transactions' from 1897 to 1996, to the contents of the Record Series volumes published from 1903 to 1997, and to the reports of the Excavation Section published between 1936 and 1940. Earlier indexes were published in 1951 and 1977; these are now superseded by this new Centenary index. Contents The index is in two parts: an author index, and an index to subjects, periods, and places. AUTHOR: this lists articles under the names of their authors or editors, giving the full title, volume number and page numbers. Where an article has more than one author or editor, it is listed by title under the name of each author or editor, with relevant volume and page numbers. SUBJECT: The contents of articles are indexed by subject and by place; topics of archaeological importance are also indexed by period. Cross-references are used to refer the enquirer from one form of heading to another, for example 'Abbeys' see ' Monastic houses', or from general headings such as 'Monastic houses' to the names of individual buildings. Place-names in the index are often followed by sub-headings indicating particular topics. -

The Communion Token: an Aid in Discipline, an Enticement for Growth

The Communion Token: An Aid in Discipline, An Enticement for Growth Angus J. Sutherland he purpose of this paper is to introduce the Communion Token, and then to trace the use and development of the Communion Token from its inception T after the Reformation until the present. What is a Communion Token? A Communion Token is a token of admission to the Lord’s Supper, found in its early days in the form of a piece of metal variously inscribed (and occasionally blank), and in its later days in the form of a card. The metal token, referred to in this paper as the Communion Token, came into use within Protestant communions in approximately 1560 and continued in use in most places until the late 1800s. The card token, hereafter called the Communion Card, has been in use from the early 1800s until today. How did the Communion Token come into being? The origins of the token can be traced back well before the Reformation. Greek and Roman civilizations used signs or tokens called tesserae or meralli for entry into celebrations, or as evidence of membership in secret societies. The Christian fish symbol may be seen to have a similar use. Tokens of various styles and taking various forms were in use over the centuries as souvenirs, passwords, introductions, and passes into special events. The beginning of the Communion Token, known generally in the French- speaking world as the marreau or méreau, is placed at the feet of John Calvin himself. In a letter to the Council of Geneva, dated 1560, Calvin wrote: [Il] serait bon que pour éviter le danger de -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Beauchief in Sheffield is a beautiful hillside at the foot of which, near the river Sheaf, and on the still wooded south-western fringes of the city, are the remains of the medieval abbey that housed, from the late twelfth century until the Henrician Reformation, Augustinian canons belonging to the Premonstratensian order. Augustinian canonries were generally modest places, although for reasons that have been persuasively advanced by the late Sir Richard Southern, this fact should never obscure the breadth of their significance in the wider history of medieval urban and rural localities: The Augustinian canons, indeed, as a whole, lacked every mark of greatness. They were neither very rich, nor very learned, nor very religious, nor very influential: but as a phenomenon they are very important. They filled a very big gap in the biological sequence of medieval religious houses. Like the ragwort which adheres so tenaciously to the stone walls of Oxford, or the sparrows of the English towns, they were not a handsome species. They needed the proximity of human habitation, and they throve on the contact which repelled more delicate organisms. They throve equally in the near-neighbourhood of a town or a castle. For the well-to-do townsfolk they could provide the amenity of burial-places, memorials and masses for the dead, and schools and confessors of superior standing for the living. For the lords of castles they could provide a staff for the chapel and clerks for the needs of administration. They were ubiquitously useful. They could live on comparatively little, yet expand into affluence without disgrace. -

Worksop Priory Primary School Admissions 2017-18

WORKSOP PRIORY C of E PRIMARY SCHOOL ADMISSION ARRANGEMENTS 2017-2018 The published admission number is 30 children per year. All applications for the Reception year will be considered in accordance with the admission criteria, as set out below. All children who are allocated a place will be admitted on the first day of the autumn term. Attendance in our early years (Foundation 1) at the school does not automatically guarantee a Reception (Foundation 2) place. Applications must be made on the Common Application Form. The offer of a school place will be made by the Local Authority to all parents on the ‘offer day’ set out in the co- ordinated scheme. The school operates a Waiting List for its intake year group in partnership with Nottinghamshire LA. This is kept and prioritised following the oversubscription criteria until the end of the autumn term. Children with a statement of Special Educational Needs or Education Health and Care Plan that names the school will be admitted. ADMISSION CRITERIA (in order of priority) 1. Looked after children and previously looked after children. 2. Children whose parents are regular worshipping members of the Church of England in any of the Worksop Priory Congregations, who have attended at least twice a month every month, for a year, immediately prior to the date of application [Priory Church and Clumber ]; 3. Children whose parents are active members of a Church within the “Churches Together in England”, who have attended at least twice a month every month, for a year, immediately prior to the date of application; Parents claiming admission under criteria 2 or 3 must complete the supplementary admission form, with Minister verification. -

LET US PRAY - Home and at Mass: for the Church in Jerusalem

LET US PRAY - home and at Mass: for the Church in Jerusalem S Paul’s & Priory Churches for those making decisions about others; with Clumber Chapel Worksop for all support and emergency workers; Easter Sunday for all working in and from our schools, hospital, hospice and GP surgeries; THIS WEEK - Missal Week – Easter Week for all struggling in isolation; MONDAY– Monday of Easter Octave for a speedy end to this pandemic; TUESDAY– Tuesday of Easter Octave WEDNESDAY– Wednesday of Easter for those who are sick: Octave Aimee Jayne, Amelia, Ann, Eileen, Jean H, Jean R, Mac, Maureen, Pat & Trevor THURSDAY- Thursday of Easter Octave FRIDAY– Friday of Easter Octave Aimee Jayne, Mary’s granddaughter, who has been diagnosed with MS SATURDAY– Saturday of Easter Octave for those who have died recently: Please be gentle and kind with yourself and Colin Hardwick, Ethel Baker, Ann Reardon, others during these days. Take every Tracy Louise Gladwin, Alan Lane, Sam precaution needed to keep yourself healthy Gawthorpe, Joyce Wagstaff. and safe. and on the anniversary of their deaths: Fr Spicer and Fr Vyse are talking each Apr 12th Margaret Emily Jackson morning to make sure we are keeping in Apr 13th Gladys Smith, Olive Mary Jarvis touch with people and to respond to prayer Apr 14th Reginald Hooton and support needs. Please contact one of Apr 15th Shelia Brunt, Brian Hamilton Cooper, pr them if you wish. In extremis we will come Apr 16th Frank Stanley Brunt, John Shaw pr, out to visit if requested. Gordon Dobbs Apr 17th Kenneth Marshall Our Churches are sadly now closed for Apr 18th Jenny Hughes everything.