The Communion Token: an Aid in Discipline, an Enticement for Growth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bygone Church Life in Scotland

*«/ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA GIFT OF Old Authors Farm Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/bygonechurchlifeOOandrrich law*""^""*"'" '* BYGONE CHURCH LIFE IN SCOTLAND. 1 f : SS^gone Cburcb Xife in Scotland) Milltam Hnbrewa . LONDON WILLIAM ANDREWS & CO., 5. FARRINGDON AVENUE, E.G. 1899. GIFT Gl f\S2S' IPreface. T HOPE the present collection of new studies -*- on old themes will win a welcome from Scotsmen at home and abroad. My contributors, who have kindly furnished me with articles, are recognized authorities on the subjects they have written about, and I think their efforts cannot fail to find favour with the reader. V William Andrews. The HuLl Press, Christmas Eve^ i8g8. 595 Contents. PAGE The Cross in Scotland. By the Rev. Geo. S. Tyack, b.a. i Bell Lore. By England Hewlett 34 Saints and Holy Wells. By Thomas Frost ... 46 Life in the Pre-Reformation Cathedrals. By A. H. Millar, F.S.A., Scot 64 Public Worship in Olden Times. By the Rev. Alexander Waters, m.a,, b.d 86 Church Music. By Thomas Frost 98 Discipline in the Kirk. By the Rev. Geo. S. Tyack, b.a. 108 Curiosities of Church Finance. By the Rev. R. Wilkins Rees 130 Witchcraft and the Kirk. By the Rev. R. Wilkins Rees 162 Birth and Baptisms, Customs and Superstitions . 194 Marriage Laws and Customs 210 Gretna Green Gossip 227 Death and Burial Customs and Superstitions . 237 The Story of a Stool 255 The Martyrs' Monument, Edinburgh .... 260 2 BYGONE CHURCH LIFE. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE COURT OF THE COMMISSARIES OF EDINBURGH: CONSISTORIAL LAW AND LITIGATION, 1559 – 1576 Based on the Surviving Records of the Commissaries of Edinburgh BY THOMAS GREEN B.A., M.Th. I hereby declare that I have composed this thesis, that the work it contains is my own and that this work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification, PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2010 Thy sons, Edina, social, kind, With open arms the stranger hail; Their views enlarg’d, their lib’ral mind, Above the narrow rural vale; Attentive still to sorrow’s wail, Or modest merit’s silent claim: And never may their sources fail! And never envy blot their name! ROBERT BURNS ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines the appointment of the Commissaries of Edinburgh, the court over which they presided, and their consistorial jurisdiction during the era of the Scottish Reformation. -

The West Front of Holyrood Abbey J Philip Mcaleer*

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 115 (1985), 263-275 A unique facade in Great Britain: the west front of Holyrood Abbey J Philip McAleer* SUMMARY The early Gothic facade of Holyrood Abbey was originally distinguished by two large towers. Although many large churches British builtthe in Isles during previousthe (12th) centurytwo had western towers, they were generally built over the westernmost bays of the nave aisles. In the case of a buildingsfew datinglaterthe to 12th earlyand 13th centuries, towersthe flanked lastthe baysthe of aisles, thereby creating widea 'screen' fagade. position towersThe the Holyroodof at distinctlywas different from either of these types. The towers were placed both outside the line of the aisle walls and in westplanefrontthe the of wall:of they were tangent corners aislesthe theirthe of to onlyof by one corners. As a result, a shallow open space was created between them, in front of the west portal. In this regard, Holyrood appears haveto been exceptional Britishthe in Isles. closestThe parallels thisfor arrangement are found at several churches on the Continent which are widely separated geographically group,and,a as without obviousany connection with each other. unusualThe system of passageways within westthe front Holyroodof also further contributes uniqueits to character. Althoug facade Augustiniae hth th f eo n abbey churc Holyroodf ho , Canongate, Edinburghs i , longeo n r complete, what does remai morf o s ni e than routine interest suggestt i r ,fo mossa t unusual arrangement facade 1.Th e stands adjacen muce th o ht later Palac Holyroodhousf eo e and, indeeds it , integrity was severely compromised by the construction of the existing north range of the Palace. -

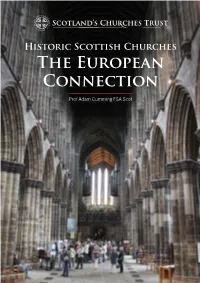

The European Connection

Historic Scottish Churches The European Connection Prof Adam Cumming FSA Scot Adam Cumming Talk “It is often assumed that Scotland took its architectural lead from England, but this is not completely true, Scotland had its own links across Europe, and these developed and changed with time.” cotland has many medieval Glasgow Cathedral which can be churches though not all are shown to have architectural links well known. They deserve across Europe. Sgreater awareness. Many The early Scottish church, that of are ruined but many are not, and Ninian and Columba (as well as many others often survive in some form in others), was part of the early church adapted buildings. before the great schism 1054. It was It is often assumed that Scotland organised a little like the Orthodox took its architectural lead from Churches now. The church below is England, but this is not completely that of Rila Monastery in Bulgaria, an true, Scotland had its own links Orthodox community and similar in across Europe, and these developed plan to early Scottish ones with the and changed with time. The changes church in the centre of the complex. were usually a response to politics It is often described as Celtic and trade. This is of course reflected which is a later description but does in the buildings across Scotland. emphasise a common base with It can be argued that these form a Ireland and Wales etc. There was distinctive part of European culture a great deal of movement across with regional variations. Right is northern Europe and it retained close links with Ireland and elsewhere via ‘Schottenkloster’ and other mission centres. -

Free Presbyterian

T H E FREE PRESBYTERIAN A MAGAZINE FOR THE DEFENCE OF BIBLE TRUTH, AND THE ADVOCACY OF FREE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH PRINCIPLES, UNDER THE DIRECTION OF A Committee of the Presbytery of the Free Presbyterian Church of South Australia. –––––––––––––––––––––––––– “The bush burned with fire, and the bush was not consumed.” – Exodus 3: 2. ––––––––––––––––––––––––– VOL. II. –––––––––––––––––––––––––– ADELAIDE R. KYFFIN THOMAS, PRINTER, GRENFELL STREET. INDEX. ––––––– A Postscript … … … 41│Confession, Alleged Erastianism, Of our 321 Articles of the Free Presbyterian Church of Victoria 107│Christian Education … … 358 A Nation's right to Worship God … 114│Discipline of the Church … 105 American Missionaries in Asia Minor … 141│Do you Pray in your Family? … 158 Amended Libel against Professor Smith … 219│Demand for Students, The … 198 An Insidious Proposal … … 243│Diversities of Christian Experience … 271 A Tale that is Told … … … 71│Dancing, Should a Christian Discountenance 295 Blotting out of Sin … … … 32│Divisions in the Church … … 324 Boyd, Dr., of St. Andrew's, defying the Almighty &c 122│Distinction between Free and Union Church 367 Bible in the Schools … … … 230│Education Difficulty in Victoria … 208 Bible Education … … … 102│Exercise of Civil Authority about Religion 364 Bible in the Schools … … … 191│Free Presbyterian Church Ecclesiastical Record 24, 85, THE FREE PRESBYTERIAN. Baptism, Dean Stanley on … … 308│ 253, 143, 213, 281, 314, 337 Burial Service … … … 329│Faith Conducive to Highest Morality 44 ════════════════════════════════════════════════════ Cardinal Antonelli's Will … … 32│Free Church of Tasmania … … 42 VOL. 2. No. 13.] APRIL 1, 1878. [PRICE 6D. Christ's Lordship over His People in Life │Newsmongers … … 249 ════════════════════════════════════════════════════ and in Death … … 33│Nathan's Fable … … 257 Covetousness … … … 129│Papal Hierarchy, The … … 16 Christ set for a Sign … … … 134│Prophetical Sketches … 13, 48, 79, 108 The Schoolmaster of the Olden Times. -

Tucker, J. (2019) Understanding Scotland's Medieval Cartularies. Innes

Tucker, J. (2019) Understanding Scotland’s medieval cartularies. Innes Review, 70(2), pp. 135-170. (doi:10.3366/inr.2019.0226) This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/202624/ Deposited on: 06 November 2019 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Understanding Scotland’s medieval cartularies1 Abstract: The medieval cartulary is well known as a major source for documents. This article takes Scotland as a case study for examining how the understanding of medieval cartularies has been shaped by those works extensively used by researchers to access cartularies and their texts—in a Scottish context this is principally the antiquarian publications and modern catalogues. Both pose their own problems for scholars seeking to understand the medieval cartulary. After an in-depth examination of these issues, a radical solution is offered which shifts the attention onto the manuscripts themselves. Such an approach reveals those extant cartularies to be fundamentally varied, and not an exclusive ‘category’ as such. This in turn allows historians to appreciate the dynamic nature of them as sources for documents, and to eschew the deeply embedded tendency to see the cartulary simply as a copy of a medieval archive. Keywords: Cartularies; charters; medieval manuscripts; antiquarian editions; modern catalogues. For -

Brechin Cathedral Round Tower

Property in Care(PIC) ID: PIC012 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90041); Listed Building (LB22440 Category A) Taken into State care: 1846 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2015 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE BRECHIN CATHEDRAL ROUND TOWER We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE BRECHIN CATHEDRAL ROUND TOWER CONTENTS 1 Summary 2 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Statement of significance 2 2 Assessment of values 2 2.1 Background 2 2.2 Evidential values 4 2.3 Historical values 4 2.4 Architectural and artistic values 4 2.5 Landscape and aesthetic values 6 2.6 Contemporary/use values 6 3 Major gaps in understanding 7 4 Associated properties 7 5 Keywords 8 Bibliography 8 APPENDICES Appendix 1: Timeline 9 Appendix 2: Summary of archaeological investigations 10 Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, 1 Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH 1 1 Summary 1.1 Introduction The monument is a medieval round tower. Originally free-standing, since 1806 it has been attached to the south west angle of the nave of Brechin Cathedral. Its chief original feature is the carved doorway, which has the crucifixion at its apex, unidentified saints on the jambs and crouching beasts flanking the threshhold. -

Brechin Cathedral Round Tower Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID:PIC012 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90041) Taken into State care: 1846 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2015 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE BRECHIN CATHEDRAL ROUND TOWER We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HISTORIC -

The Development of Dunfermline Abbey As a Royal Cult Centre C.1070-C.1420

The Development of Dunfermline Abbey as a royal cult centre c.1070-c.1420 SangDong Lee A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Stirling February 2014 Contents Page No. Declaration ii Abstract iii Acknowledge iv Abbreviations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The Miracles of St Margaret and Pilgrimage to Dunfermline (1) Introduction 15 (2) The collection of miracles and its collectors 18 (3) The recipients of St Margaret's miracles 31 (4) The genres of St Margaret's miracles 40 (5) The characteristics of St Margaret's miracles 54 (6) Pilgrimage to Dunfermline 64 (7) Conclusion 80 Chapter 2: Lay patronage of Dunfermline Abbey 1) Introduction 85 (2) David I (1124-53) 93 (3) Malcolm IV (1153-65) 105 (4) William I (1165-1214) 111 (5) Alexander II (1214-1249) 126 (6) Alexander III (1249-86) 136 (7) The Guardians, John Balliol and pre-Robert I (1286-1306) 152 (8) Robert I (1306-1329) 158 (9) David II (1329-71) 166 (10) The Early Stewart Kings (1371-1406) 176 (11) Conclusion 188 Chapter 3: The Liturgical and Devotional Space of Dunfermline Abbey (1) Introduction 201 (2) The earlier church, c.1070-1124 208 (3) The Twelfth century church 229 (4) The Thirteenth century church 251 (5) The Fourteenth century church 278 (6) Conclusion 293 Conclusion 297 Bibliography 305 i Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis has been composed by myself, and that the work which it embodies has been done by myself and has not been included in any other thesis. -

Ministerial Dress for Worship from the Perspective of Southern Africa Presbyterianism Graham a Duncan

The Church Service Society Record Ministerial Dress for Worship from the perspective of Southern Africa Presbyterianism Graham A Duncan Church Clothes The chameleon charms with wizardry to escape his humble lizardry, blending in with vain show blizzardry, Chameleon is confused. The peacock moves with pageantry, unfolding feathered tapestry, to hide would be disastery, Peacock is convinced. And which will dress our history, bold plumes or image shiftery? Word, sacrament and mystery, or blending in confused? Richard C. Lambert Introduction 'Any uniformity in clerical dress among Presbyterian ministers has never been realised, particularly in America.' (Macleod 1990:126) This is also true in southern Africa since the union which brought the Uniting Presbyterian Church in Southern Africa (UPCSA) into being in 1999. Prior to that, the former Reformed Presbyterian Church in Southern Africa (RPCSA) had a distinctive approach to ministerial dress which was inherited directly from Scotland and was very formal.' The Presbyterian Church in Southern Africa (PCSA) had two traditions; one was identical to that of the RPCSA; the other is far less formal and depends predominantly on the ethos of individual congregations. However, within these broad traditions there are variations in dress. The union has highlighted these differences in practice and there would appear to be a desire on the part of some to achieve a degree of uniformity. Whether 2007/8 25 The Church Service Society Record that is a good thing or not is also a contentious issue. A recent debate on the design of the UPCSA Moderator of General Assembly's stole demonstrated how so much time and energy can be devoted to a matter that is simply not of the `substance of the faith' and therefore could be considered a matter where `liberty of opinion' is exercised. -

Annex 6 SCOTLAND's CASTLES, PALACES, ABBEYS & OTHER

CERWG Final Report December 2006 Annex 6 SCOTLAND’S CASTLES, PALACES, ABBEYS & OTHER HISTORIC NATIONAL PROPERTIES Introduction 1. This paper reports on a major transfer of property from the Crown Estate in Scotland to Scottish Ministers at the time of devolution. The paper examines two issues associated with the transfer: - the apparent lack of information available about the extent and purpose of the transfer; - the unusual nature of the reservations retained in favour of the Crown in the transfer; Historic Transfer 2. The CERWG learnt during the course of its investigations that the Crown Estate Commission (CEC) had conveyed the ownership of Edinburgh and Stirling Castles and a number of Scotland’s other castles, palaces, abbeys and other historic properties to the Secretary of State for Scotland at the time of devolution. 3. These properties were conveyed by the CEC on behalf of the Crown to the Secretary of State one by one during 19991. The ownership of the properties then passed from the Secretary of State to Scottish Ministers as a result of devolution and the terms of the Scotland Act 1998. 4. The CERWG was not aware of a publicly available list of all the properties involved in the transfer and enquiries to the CEC and Scottish Executive initially produced no results. A brief search of the Land Register and Register of Sasines showed that the properties involved in addition to Edinburgh and Stirling Castles, were in a number of different counties and also of considerable individual national significance (for example, Blackness Castle, Linlithgow Palace, Dunfermline Abbey). 5. -

A Stained Glass Masterpiece in Victorian Glasgow

A STAINED GLASS MASTERPIECE IN VICTORIAN GLASGOW STEPEHEN ADAM’S CELEBRATION OF INDUSTRIAL LABOR Lionel Gossman with Ian R. Mitchell and Iain B. Galbraith 1 A STAINED GLASS MASTERPIECE IN VICTORIAN GLASGOW STEPHEN ADAM’S CELEBRATION OF INDUSTRIAL LABOR by Lionel Gossman with Ian R. Mitchell and Iain B. Galbraith 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Prefatory Note and Acknowledgments (pp. 3-9) Maryhill Burgh Halls Album (pp. 10-14) Part I. “Cinderella to her Sister Arts.” Reflections on the Standing of Stained Glass as Art. (pp. 15-38) Part II. Stephen Adam’s Work in Historical Context. 1. The Revival of Stained Glass in the Nineteenth Century. (pp. 39-58) 2. Charles Winston on Stained Glass. (pp. 59-68) 3. Stephen Adam on Stained Glass. (pp. 69-93) Part III. The Maryhill Burgh Halls Panels 1. Stephen Adam: The Early Years and the Glasgow Studio. (pp. 94-117) 2. “A man perfects himself by working.” (pp.118-135) 3. An Original Style. Realism and Neo-Classicism in the Maryhill Panels. (pp. 136-157) Endnotes. (pp. 158-188) Appendix I. “The Maryhill Panels: Stephen Adam’s Stained Glass Workers” by Ian R. Mitchell. (pp. 189-204) Appendix II. “’Always happy in his Designs’: the Legacy of Stephen Adam” by Iain B. Galbraith. (pp. 205-220) Appendix III. Chronology of Works in Stained Glass by Stephen Adam. (pp. 221-236) 3 PREFATORY NOTE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Burgh Halls of Maryhill – a district in the north-western section of Glasgow1 -- are adorned by twenty stained glass panels of extraordinary power, beauty, and originality. Created some time between 1877 and 1881 by the barely thirty-year old Stephen Adam in collaboration with David Small, his partner in the studio he opened in Glasgow in 1870, these panels are unique among stained glass works of the time in that they depict the workers of the then independent burgh not for the most part in the practice of traditional trades (baker, weaver, flesher, cooper, hammerman, etc.) (see Pt.