Brechin Cathedral Round Tower

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRUCIS Magazine of St

CRUCIS Magazine of St. Salvador’s Scottish Episcopal Church Dundee May 2016 “Far be it from me to glory except in the cross of Christ, by which the world has been crucified to me and I to the world.” Galatians 6:14 In the Beginning… what challenges were left? Monastic life was the response by the Spirit in the I recently received a nice postcard from one Church. of our members visiting Pluscarden Abbey near Forres. It got me thinking about the There is something austere at the core of calling of some Christians to the Religious Christianity. It is the call to respond to Our Life. Lord’s invitation to leave everything be- hind, take up the cross, and follow Him. He- We seldom think about monks and nuns, do roic holiness is an authentic part of the we? Monasteries and convents are often in Christian vocation. The Religious Life is a “out of the way” places. And what goes on reminder to us of this. in them is largely unknown and often mys- terious to most people. We may be attracted As with all ministries in the Church, certain to the perceived tranquillity of the life, but callings exist for the good of all. They em- rebel at the thought of its discipline. We phasise to an intense degree something may fear boredom. The Religious Life may about the life in Christ that all of us share to fascinate and yet at the same time repel us. a lesser extent. All of us are Priests, but Hardly anyone we know may have actually some are called to the Sacred Ministry to tested their vocation to it, or know anything exemplify that aspect of Christian living. -

Memorandum Regarding the Fairweathers of Menmuir Parish

4- Ilh- it National Library of Scotland *B000448350* 7& A 7^ JUv+±aAJ icl^^ MEMORANDUM REGARDING THE FAIRWEATHER'S OF MENMUIR PARISH, FORFARSHIRE, AND OTHERS OF THE SURNAME, BY ALEXANDER FAIRWEATHER. EDITED, WITH NOTES, ADDITIONS AND CORRECTIONS, BY WILLIAM GERARD DON, M.D. PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION LONDON : Dunbar & Co., 31, Marylebone Lane, W 1898. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/memorandumregard1898fair CONTENTS I. Introductory. II. Of the Name in General. III. Of the Angus Fairweathers. APPENDICES. I. Kirriemuir Fairweathers. II. Intermarriage, Dons, Fairweathers, Leightons. III. Intermarriage, Leightons, Fairweathers. IV. Intermarriage, Smiths, Fairweathers. V. List of Fairweathers. VI. Fairweathers of Langhaugh. VII. Fairweathers Mill of Ballhall. VIII. Christian Names, Fairweathers. IX. Occupations, Fairweathers. — ; INTRODUCTORY. LEXANDER FAIRWEATHER, at one time Merchant in Kirriemuir, afterwards resident at Newport, Dundee, about the year 1874, wrote this Memorandum, or History ; to which he proudly affixed the following lines : " Our name and ancestry renowned or no, Free from dishonour, 'tis our pride to show." As his memorandum exists only in manuscript, and so might easily be lost, I proprose to re-edit it for printing ; with such notes, and corrections as I can furnish. Mr. Fairweather had sound literary tastes, and was a keen archaeologist and genealogist ; upon which subjects he brought to bear a considerable amount of critical acumen. The deep interest he took in everything connected with his family and surname naturally endeared him to all his kin while, unfailing geniality and lively intelligence, made him a wide circle of attached friends, ! ; 6 I only met him once, when he visited Jersey in 1876 where I happened to be quartered, with the Royal Artillery, and where he sought me out. -

Bygone Church Life in Scotland

*«/ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA GIFT OF Old Authors Farm Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/bygonechurchlifeOOandrrich law*""^""*"'" '* BYGONE CHURCH LIFE IN SCOTLAND. 1 f : SS^gone Cburcb Xife in Scotland) Milltam Hnbrewa . LONDON WILLIAM ANDREWS & CO., 5. FARRINGDON AVENUE, E.G. 1899. GIFT Gl f\S2S' IPreface. T HOPE the present collection of new studies -*- on old themes will win a welcome from Scotsmen at home and abroad. My contributors, who have kindly furnished me with articles, are recognized authorities on the subjects they have written about, and I think their efforts cannot fail to find favour with the reader. V William Andrews. The HuLl Press, Christmas Eve^ i8g8. 595 Contents. PAGE The Cross in Scotland. By the Rev. Geo. S. Tyack, b.a. i Bell Lore. By England Hewlett 34 Saints and Holy Wells. By Thomas Frost ... 46 Life in the Pre-Reformation Cathedrals. By A. H. Millar, F.S.A., Scot 64 Public Worship in Olden Times. By the Rev. Alexander Waters, m.a,, b.d 86 Church Music. By Thomas Frost 98 Discipline in the Kirk. By the Rev. Geo. S. Tyack, b.a. 108 Curiosities of Church Finance. By the Rev. R. Wilkins Rees 130 Witchcraft and the Kirk. By the Rev. R. Wilkins Rees 162 Birth and Baptisms, Customs and Superstitions . 194 Marriage Laws and Customs 210 Gretna Green Gossip 227 Death and Burial Customs and Superstitions . 237 The Story of a Stool 255 The Martyrs' Monument, Edinburgh .... 260 2 BYGONE CHURCH LIFE. -

The Arms of the Scottish Bishoprics

UC-NRLF B 2 7=13 fi57 BERKELEY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A \o Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/armsofscottishbiOOIyonrich /be R K E L E Y LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A h THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS. THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS BY Rev. W. T. LYON. M.A.. F.S.A. (Scot] WITH A FOREWORD BY The Most Revd. W. J. F. ROBBERDS, D.D.. Bishop of Brechin, and Primus of the Episcopal Church in Scotland. ILLUSTRATED BY A. C. CROLL MURRAY. Selkirk : The Scottish Chronicle" Offices. 1917. Co — V. PREFACE. The following chapters appeared in the pages of " The Scottish Chronicle " in 1915 and 1916, and it is owing to the courtesy of the Proprietor and Editor that they are now republished in book form. Their original publication in the pages of a Church newspaper will explain something of the lines on which the book is fashioned. The articles were written to explain and to describe the origin and de\elopment of the Armorial Bearings of the ancient Dioceses of Scotland. These Coats of arms are, and have been more or less con- tinuously, used by the Scottish Episcopal Church since they came into use in the middle of the 17th century, though whether the disestablished Church has a right to their use or not is a vexed question. Fox-Davies holds that the Church of Ireland and the Episcopal Chuich in Scotland lost their diocesan Coats of Arms on disestablishment, and that the Welsh Church will suffer the same loss when the Disestablishment Act comes into operation ( Public Arms). -

CRUCIS Magazine of St

CRUCIS Magazine of St. Salvador’s Scottish Episcopal Church Dundee September 2009 “Far be it from me to glory except in the cross of Christ, by which the world has been crucified to me and I to the world.” Galatians 6:14 spelled exactly the same), the Saint carried the Christ Child. The server who carries the Cross (“crucis”) in Church processions is called the “Crucifer”. Often the Crucifer is specially clothed in a decorated garment with sleeves called a “tunicle”. Why? I suppose, with the Cross carried at the head of the procession, it adds some colour, but I think there’s more to it than that. There’s something special about carrying the Cross. We vest the Crucifer with his own special garment to emphasise that particular idea. But the original Crucifer was not such a pretty sight. And I don’t mean the Emperor. Our Lord was Himself the original Crucifer In the Beginning… – the One who carried the Cross to Calvary. Holy Cross Day is sometimes known as the He was half-dead from being tortured and Feast of the Exaltation (or Triumph) of the bled from his many wounds. His only Holy Cross. It commemorates the retrieval adornment was a crown of thorns. There on of the supposed relic of the Holy Cross Calvary Hill He offered His unique and from the Persians in the year 629 and its bloody sacrifice for our sins, the same sacri- triumphant return to Jerusalem, carried per- fice that Christians share every time we sonally by the Emperor, divested of his im- gather for the Holy Eucharist. -

Diocese of Brechin: News Bulletin 30Th March 2021

Diocese of Brechin: News Bulletin 30th March 2021 Rev David Shepherd RIP the same commission that is given to every minister of God’s word and sacrament – “feed my lambs; 1942-2021 tend my shearlings; feed my sheep.” The Rev David Shepherd died on Saturday 27th “So many christenings in Saint Mary Magdalene’s! — March 2021 following an extended time of illness. The Baptismal Register shows no less than eight He retired as the Rector of St Mary Magdalene’s hundred and sixty lambs nourished and in their Scottish Episcopal Church on Easter Day 2020 after baptisms given the grace to lead Christian lives. And over 40 years’ service to that church and nearly 53 even in these recent months there has been more years of ordained ministry in the Diocese of Brechin. nourishment, in the shape of a splendidly produced volume of Bible stories for children. David started his ordained ministry as a “And then the shearlings , those young and curate at St Paul’s sometimes wayward, members of the flock. In those Cathedral, Dundee, in halcyon days in Saint Paul’s Cathedral in the 1968, and his ministry seventies. Who could ever forget David’s Sixty-Nine at St Mary Magdalene Club, with a hundred and fifty young people meeting started in 1979. He in the hall every week! His six years as Chaplain to built up and main- Anglican Students in the University of Dundee, some tained that worship- of whom have remained in touch. ping community and ““Feed my sheep.” —The ordinary day-to-day of the their building in the flock. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2021

PORVOO PRAYER DIARY 2021 The Porvoo Declaration commits the churches which have signed it ‘to share a common life’ and ‘to pray for and with one another’. An important way of doing this is to pray through the year for the Porvoo churches and their Dioceses. The Prayer Diary is a list of Porvoo Communion Dioceses or churches covering each Sunday of the year, mindful of the many calls upon compilers of intercessions, and the environmental and production costs of printing a more elaborate list. Those using the calendar are invited to choose one day each week on which they will pray for the Porvoo churches. It is hoped that individuals and parishes, cathedrals and religious orders will make use of the Calendar in their own cycle of prayer week by week. In addition to the churches which have approved the Porvoo Declaration, we continue to pray for churches with observer status. Observers attend all the meetings held under the Agreement. The Calendar may be freely copied or emailed for wider circulation. The Prayer Diary is updated once a year. For corrections and updates, please contact Ecumenical Officer, Maria Bergstrand, Ms., Stockholm Diocese, Church of Sweden, E-mail: [email protected] JANUARY 3/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Sarah Mullally, Bishop Graham Tomlin, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Rob Wickham, Bishop Jonathan Baker, Bishop Ric Thorpe, Bishop Joanne Grenfell. Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Olav Fykse Tveit, Bishop Herborg Oline Finnset 10/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Jukka Keskitalo Church of Norway: Diocese of Sør-Hålogaland (Bodø), Bishop Ann-Helen Fjeldstad Jusnes Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Christopher Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE COURT OF THE COMMISSARIES OF EDINBURGH: CONSISTORIAL LAW AND LITIGATION, 1559 – 1576 Based on the Surviving Records of the Commissaries of Edinburgh BY THOMAS GREEN B.A., M.Th. I hereby declare that I have composed this thesis, that the work it contains is my own and that this work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification, PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2010 Thy sons, Edina, social, kind, With open arms the stranger hail; Their views enlarg’d, their lib’ral mind, Above the narrow rural vale; Attentive still to sorrow’s wail, Or modest merit’s silent claim: And never may their sources fail! And never envy blot their name! ROBERT BURNS ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines the appointment of the Commissaries of Edinburgh, the court over which they presided, and their consistorial jurisdiction during the era of the Scottish Reformation. -

The West Front of Holyrood Abbey J Philip Mcaleer*

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 115 (1985), 263-275 A unique facade in Great Britain: the west front of Holyrood Abbey J Philip McAleer* SUMMARY The early Gothic facade of Holyrood Abbey was originally distinguished by two large towers. Although many large churches British builtthe in Isles during previousthe (12th) centurytwo had western towers, they were generally built over the westernmost bays of the nave aisles. In the case of a buildingsfew datinglaterthe to 12th earlyand 13th centuries, towersthe flanked lastthe baysthe of aisles, thereby creating widea 'screen' fagade. position towersThe the Holyroodof at distinctlywas different from either of these types. The towers were placed both outside the line of the aisle walls and in westplanefrontthe the of wall:of they were tangent corners aislesthe theirthe of to onlyof by one corners. As a result, a shallow open space was created between them, in front of the west portal. In this regard, Holyrood appears haveto been exceptional Britishthe in Isles. closestThe parallels thisfor arrangement are found at several churches on the Continent which are widely separated geographically group,and,a as without obviousany connection with each other. unusualThe system of passageways within westthe front Holyroodof also further contributes uniqueits to character. Althoug facade Augustiniae hth th f eo n abbey churc Holyroodf ho , Canongate, Edinburghs i , longeo n r complete, what does remai morf o s ni e than routine interest suggestt i r ,fo mossa t unusual arrangement facade 1.Th e stands adjacen muce th o ht later Palac Holyroodhousf eo e and, indeeds it , integrity was severely compromised by the construction of the existing north range of the Palace. -

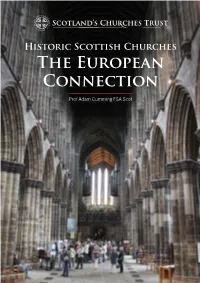

The European Connection

Historic Scottish Churches The European Connection Prof Adam Cumming FSA Scot Adam Cumming Talk “It is often assumed that Scotland took its architectural lead from England, but this is not completely true, Scotland had its own links across Europe, and these developed and changed with time.” cotland has many medieval Glasgow Cathedral which can be churches though not all are shown to have architectural links well known. They deserve across Europe. Sgreater awareness. Many The early Scottish church, that of are ruined but many are not, and Ninian and Columba (as well as many others often survive in some form in others), was part of the early church adapted buildings. before the great schism 1054. It was It is often assumed that Scotland organised a little like the Orthodox took its architectural lead from Churches now. The church below is England, but this is not completely that of Rila Monastery in Bulgaria, an true, Scotland had its own links Orthodox community and similar in across Europe, and these developed plan to early Scottish ones with the and changed with time. The changes church in the centre of the complex. were usually a response to politics It is often described as Celtic and trade. This is of course reflected which is a later description but does in the buildings across Scotland. emphasise a common base with It can be argued that these form a Ireland and Wales etc. There was distinctive part of European culture a great deal of movement across with regional variations. Right is northern Europe and it retained close links with Ireland and elsewhere via ‘Schottenkloster’ and other mission centres. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2021

PORVOO PRAYER DIARY 2021 The Porvoo Declaration commits the churches which have signed it ‘to share a common life’ and ‘to pray for and with one another’. An important way of doing this is to pray through the year for the Porvoo churches and their Dioceses. The Prayer Diary is a list of Porvoo Communion Dioceses or churches covering each Sunday of the year, mindful of the many calls upon compilers of intercessions, and the environmental and production costs of printing a more elaborate list. Those using the calendar are invited to choose one day each week on which they will pray for the Porvoo churches. It is hoped that individuals and parishes, cathedrals and religious orders will make use of the Calendar in their own cycle of prayer week by week. In addition to the churches which have approved the Porvoo Declaration, we continue to pray for churches with observer status. Observers attend all the meetings held under the Agreement. The Calendar may be freely copied or emailed for wider circulation. The Prayer Diary is updated once a year. For corrections and updates, please contact Ecumenical Officer, Cajsa Sandgren, Ms., Ecumenical Department, Church of Sweden, E-mail: [email protected] JANUARY 10/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Sarah Mullally, Bishop Graham Tomlin, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Rob Wickham, Bishop Jonathan Baker, Bishop Ric Thorpe, Bishop Joanne Grenfell. Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Olav Fykse Tveit, Bishop Herborg Oline Finnset 17/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Jukka Keskitalo Church of Norway: Diocese of Sør-Hålogaland (Bodø), Bishop Ann-Helen Fjeldstad Jusnes Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Christopher Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. -

Diocese of Brechin: News Bulletin 22Nd April 2021 New Priest for Episcopal Churches in Diocese of St Edmundsbury and Ipswich

Diocese of Brechin: News Bulletin 22nd April 2021 New Priest for Episcopal Churches in Diocese of St Edmundsbury and Ipswich. In his present role in the Diocese of York he has a wide Carnoustie and Monifieth range of interests and responsibilities in church, Bishop Andrew and the vestries of the Church of the schools and community. He has undertaken training Holy Rood, Carnoustie and Holy Trinity, Monifieth for spiritual direction and has experience in a wide are delighted to announce that the Revd Martin range of church growth and development areas. Allwood has been selected to be the new priest to Martin enjoys the outdoors and is a keen kayaker lead and serve these church communities on the and is looking forward to making links within the Angus coast. local clubs. Martin is currently Martin said, “I am delighted to accept the invitation Rector of the to be part of the next stage of the journey in the Benefice of Street Carnoustie and Monifieth charges. My wife, Colleen Parishes comprising and I look forward to being a part of the Diocese of Amotherby, Barton- Brechin, meeting new colleagues and friends, and Le-Street, Hoving- experiencing the area's weather (which we have ham, and Slingsby in been told is constantly sunny!)”. the Diocese of York Martin’s role is to be both the priest for the two in the Church of charges and also a ‘transitional minister’, where England, a post he churches are guided by a specially trained and has held since 2014. supported cleric to work together and explore their Martin is married to history, present gifts and future possibilities.