Gaposchkin2017.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on Psalms 2015 Edition Dr

Notes on Psalms 2015 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable Introduction TITLE The title of this book in the Hebrew Bible is Tehillim, which means "praise songs." The title adopted by the Septuagint translators for their Greek version was Psalmoi meaning "songs to the accompaniment of a stringed instrument." This Greek word translates the Hebrew word mizmor that occurs in the titles of 57 of the psalms. In time the Greek word psalmoi came to mean "songs of praise" without reference to stringed accompaniment. The English translators transliterated the Greek title resulting in the title "Psalms" in English Bibles. WRITERS The texts of the individual psalms do not usually indicate who wrote them. Psalm 72:20 seems to be an exception, but this verse was probably an early editorial addition, referring to the preceding collection of Davidic psalms, of which Psalm 72 was the last.1 However, some of the titles of the individual psalms do contain information about the writers. The titles occur in English versions after the heading (e.g., "Psalm 1") and before the first verse. They were usually the first verse in the Hebrew Bible. Consequently the numbering of the verses in the Hebrew and English Bibles is often different, the first verse in the Septuagint and English texts usually being the second verse in the Hebrew text, when the psalm has a title. ". there is considerable circumstantial evidence that the psalm titles were later additions."2 However, one should not understand this statement to mean that they are not inspired. As with some of the added and updated material in the historical books, the Holy Spirit evidently led editors to add material that the original writer did not include. -

A L'atenció De

Generalitat de Cataluña Departamento de Cultura y Medios de Comunicación Oficina de Comunicación y Prensa La Obra Social ”la Caixa” llega a un acuerdo con la Generalitat para invertir 18 millones de euros en la restauración y mejora del románico catalán El presidente de la Generalitat, José Montilla, y el presidente de ”la Caixa”, Isidre Fainé, firman un convenio de colaboración para el desarrollo del Programa Románico Abierto. La inversión de la Obra Social ”la Caixa” permitirá actuar en un total de 74 monumentos del patrimonio catalán hasta el año 2013, y acelerar la rehabilitación, la mejora y la difusión del arte románico catalán. Gracias a la nueva iniciativa de ”la Caixa” para la conservación del patrimonio arquitectónico catalán, se actuará en las iglesias románicas de la Vall de Boí, declaradas Patrimonio Mundial por la UNESCO en el año 2000, y en monasterios como los de Poblet y Santa Maria de Ripoll. Esta actuación se inscribe en la política de ambas instituciones de cooperar en la realización conjunta de iniciativas de interés social y cultural, mediante un convenio anual. Barcelona, 8 de enero de 2009.- La Generalitat, a través del Departamento de Cultura y Medios de Comunicación, y la Obra Social ”la Caixa” impulsarán el Programa Románico Abierto, cuyo objetivo es «dar un impulso renovado a la puesta en valor, revisión, mejora y prevención de este importante legado patrimonial». Así consta en el convenio de colaboración entre ambas instituciones, firmado hoy por el presidente de la Generalitat, José Montilla, y el presidente de ”la Caixa”, Isidre Fainé. Al acto ha asistido el consejero de Cultura y Medios de Comunicación, Joan Manuel Tresserras. -

Santa María De Ripoll: Vicisitudes Históricas De Una Portada Románica

santa María de ripoll: Vicisitudes históricas de una portada románica El estado de conservación de la portada románica de Ripoll es fruto tanto del “mal de piedra” detectado hacia 1959, y donde José María Cabrera Garrido actuó entre 1964 y 1974, como de una larga serie de vicisitudes his- tóricas (terremotos, sacudidas, depredaciones, elementos generadores de humedad, contaminación histórica ambiental, etc.), las cuales hay que tener muy en cuenta cuando se quiere emprender cualquier actuación de conservación o de mejora de la realidad existente. Antoni Llagostera Fernández. Presidente del Centro de Estudios del Ripollés. [email protected] Fotografía que muestra el estado de la portada románica, de la serie del año 1879 hecha por encargo de la Associació Catalana d’Excursions (Fotografía: Marc Sala). [pág.41] [161] Unicum Versión castellano INTRODUCCIÓN do hay que añadir un factor hasta ahora poco explicado: la 1 Salvador ALIMBAU MAR- La preocupación sobre el estado de conservación de la por- existencia de elementos químicos de enlucimiento barrocos. QUÈS, Antoni LLAGOSTERA tada románica de Ripoll, desde finales de los años cincuenta FERNÁNDEZ, Elies ROGENT del siglo XX, ha sido un tema de palpitante actualidad. Y aún Montserrat Artigau y Eduard Porta explican en su trabajo de AMAT, Jordi ROGENT ALBIOL, hoy, la resonancia de la actuación realizada por José María 2002: “Una de las causas de la presencia del sulfato cálcico Pantocràtor de Ripoll. Cabrera Garrido no se ha apagado. es debida a un veteado que se hizo en época barroca: -

PDF Catalogue

1 GAUL, Massalia, c. 200-120 BCE, AR obol. 0.60g, 9mm. Obv: Bare head of Apollo left Rev: M A within wheel of four spokes. Depeyrot, Marseille 31 From the JB (Edmonton) collection. Obverse off-centre, but high grade, superb style, perfect metal, and spectacular toning. Estimate: 100 Starting price: 50 CAD 2 CIMMERIAN BOSPORUS, Pantikapaion, c. 310-303BC, AE 22. 7.61g, 21.5mm Obv: Bearded head of Satyr (or Pan), right Rev: P-A-N, forepart of griffin left, sturgeon left below Anokhin 1023; MacDonald 69; HGC 7, 113 Ex Lodge Antiquities Estimate: 100 Starting price: 50 CAD 3 CIMMERIAN BOSPOROS, Pantikapaion, c. 325-310 BCE, AE17. 3.91g, 17mm. Obv: Head of satyr left Rev: ΠΑΝ; Head of bull left. MacDonald 67; Anokhin 1046 From the JB (Edmonton) collection. Starting price: 30 CAD 4 THESSALY, Atrax, 3rd c. BCE, AE trichalkon. 6.03g, 18mm. Obv: Laureate head of Apollo right Rev: ATP-A-Γ-IΩN, horseman, raising right hand, advancing right. Rogers 169-71; BCD Thessaly II 59.6-10 Starting price: 30 CAD 5 THESSALY, Krannon, circa 350-300 BCE, AE chalkous. 2.41g, 15.4mm. Obv: Thessalian warrior on horse rearing right. Rev: KPAN, bull butting right; above, trident right. BCD Thessaly II 118.5; HGC 4, 391 From the zumbly collection; ex BCD Collection, with his handwritten tag stating, “V. Ex Thess., Apr. 94, DM 35” Starting price: 30 CAD 6 THESSALY, Phalanna, c. 350 BCE, AE 18 (dichalkon or trichalkon). 6.53g, 17.5mm. Obv: Head of Ares right, A to left . -

The Holy Lance of Antioch

The Holy Lance of Antioch A Study on the Impact of a Perceived Relic during the First Crusade Master Thesis By Marius Kjørmo The crucified Jesus and the Roman soldier Longinus with the spear that would become the Holy Lance. Portrait by Fra Angelico from the Dominican cloister San Marco, Florence. A Master Thesis in History, Institute of Archaeology, History, Culture Studies and Religion, University of Bergen, Spring 2009. 2 Contents Preface.........................................................................................................................................5 List of Maps..................................................................................................................................6 List of Illustrations.......................................................................................................................6 Cast of Characters.......................................................................................................................7 1. Introduction.........................................................................................................................................9 1.1. Introduction...........................................................................................................................9 1.2. Lance Historiography..........................................................................................................11 1.3. Terms and Expressions.......................................................................................................13 -

University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Art History Newsletter September 2014

University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Art History Newsletter September 2014 Chipstone Foundation Supports Launch of Curatorial Studies with 75k Grant As Art History introduces new curatorial studies courses in the builds on previous support in those areas. Chipstone has lent fall, we are pleased to announce that the Chipstone Foundation significant works of American furniture and ceramics from its of Milwaukee has generously agreed to support the curriculum collection to the Chazen Museum of Art for use in teaching and with a grant of $75,000.00. Chipstone is already the depart- in two exhibitions organized by Ann Smart Martin. It has also ment’s most generous donor. In addition to funding the Stanley supported three exhibitions at the Milwaukee Art Museum cu- and Polly Stone Professor of American Decorative Arts and rated by graduate students of our department (Megan Doherty, Material Culture (beginning in 1998) and the program budget B.A. Harrington, and Emily Pfotenhauer). Furthermore, a gen- for Material Culture, over the past fifteen years, Chipstone has erous grant of $10,000.00 from Chipstone supported the Think supported summer internships for undergraduates at Historical Tank on Curatorial Studies in April 2013. Societies throughout Wisconsin, endowed the WDGF Chipstone The new grant will support programing and publication of stu- -Watrous Fellowship in American Decorative Arts and Material dent research for exhibition courses, curatorial internships, a Culture (starting July 1999), and funded two crucial research Curatorial Innovations Fund that will provide seed grants to tools for the decorative arts: the Digital Library for the Decora- students for individual curatorial projects, and a special Decora- tive Arts hosted by UW-Memorial Library, and The Wisconsin tive Arts/Material Culture exhibition fund to support future pro- Decorative Arts Database, hosted by the Wisconsin Historical jects including an exhibition on Global Linkages in Design and Society. -

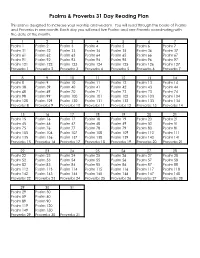

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

Vallfogona and the Vall De Sant Joan: a Community in the Grip Of

72 Vallfogona and the Vall de Sant Joan: a community in the grip of change Sant Joan de Ripoll and the Evidence One of the more concentrated bodies of this problematic evidence has been left to us by the monastery of Sant Joan de Ripoll, now known as Sant Joan de les Abadesses. Now a parish church, it is sited in the Ripoll valley, slightly further up the Ter than its sister foundation of Santa Maria. 1 Unlike that house, 2 Sant Joan has left us a considerable part of its documentation. We know from a sixteenth-century inventory of the archive which is preserved in the first volume of the monastery’s Llibre de Canalars that what we now have, either at Sant Joan or for the most part in the Arxiu de la Corona de Aragó in Barcelona, is only about half of what was once there. Despite the losses, partially offset by the regesta in the Llibre de Canalars , the ninth- and tenth-century material for the monastery and its immediate environs is plentiful by most standards. In particular, the monastery’s own valley and the neighbouring one of Vallfogona furnish us with just over one hundred and fifty charters between 885 and an arbitrary cut-off point of 1030, and in that sequence concentrated more towards to the early tenth century when the monastery was most active in 1 There are two short volumes on Sant Joan, J. Masdeu, St. Joan de les Abadesses: resum historic (Vic 1926) and E. Albert i Corp, Les Abadesses de Sant Joan: verificació històrica , Episodis de la Història 69 (Barcelona 1965); both are hard to find and a more modern summary will be found in A. -

Timeline1800 18001600

TIMELINE1800 18001600 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 8000BCE Sharpened stone heads used as axes, spears and arrows. 7000BCE Walls in Jericho built. 6100BCE North Atlantic Ocean – Tsunami. 6000BCE Dry farming developed in Mesopotamian hills. - 4000BCE Tigris-Euphrates planes colonized. - 3000BCE Farming communities spread from south-east to northwest Europe. 5000BCE 4000BCE 3900BCE 3800BCE 3760BCE Dynastic conflicts in Upper and Lower Egypt. The first metal tools commonly used in agriculture (rakes, digging blades and ploughs) used as weapons by slaves and peasant ‘infantry’ – first mass usage of expendable foot soldiers. 3700BCE 3600BCE © PastSearch2012 - T i m e l i n e Page 1 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 3500BCE King Menes the Fighter is victorious in Nile conflicts, establishes ruling dynasties. Blast furnace used for smelting bronze used in Bohemia. Sumerian civilization developed in south-east of Tigris-Euphrates river area, Akkadian civilization developed in north-west area – continual warfare. 3400BCE 3300BCE 3200BCE 3100BCE 3000BCE Bronze Age begins in Greece and China. Egyptian military civilization developed. Composite re-curved bows being used. In Mesopotamia, helmets made of copper-arsenic bronze with padded linings. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, first to use iron for weapons. Sage Kings in China refine use of bamboo weaponry. 2900BCE 2800BCE Sumer city-states unite for first time. 2700BCE Palestine invaded and occupied by Egyptian infantry and cavalry after Palestinian attacks on trade caravans in Sinai. 2600BCE 2500BCE Harrapan civilization developed in Indian valley. Copper, used for mace heads, found in Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Sumerians make helmets, spearheads and axe blades from bronze. -

Project 119 Bible Reading Plan May 3-June 6, 2020 Proverbs & Psalms

Project 119 Bible Reading Plan May 3-June 6, 2020 Proverbs & Psalms 105-129 Are you looking for wisdom on how to best live life in these challenging times? Perhaps you’ve been tempted to watch the news constantly, to keep up-to-date with what is happening in the world with COVID-19, how stock markets are responding, and what the future might hold. Maybe you’ve spent the days scrolling through your social media, in an attempt to escape reality or learn new tips for dealing with life in a pandemic. While watching the news and engaging in social media aren’t inherently bad things (in fact, Scripture calls us to be engaged with what is happening in the world, to pray for our leaders and public officials, and social media can provide a great opportunity to check in on loved ones in these odd days), in Proverbs 1:7, we learn that “the fear of the LORD is the beginning of knowledge; fools despise wisdom and instruction.” During these next five weeks, we want to challenge you to devote time every day to seek out wisdom by reading God’s word. We’ll read through the book of Proverbs over these five weeks, along with selected Psalms which could be used for your morning or evening prayers. There are five days of reading each week, giving you two days to reflect on what you’ve read or catch up on any reading you have missed. We hope you’ll join us in this journey through Proverbs as we all seek out the wisdom that God has for us in His word. -

The Glossed Psalter Psalm Texts Notes Psalm 119 Psalm

The Glossed Psalter Psalm Texts Notes (90r) <V>ivet a(ni)ma m(e)a et laudabit te et iudicia tua adiu | vab(un)t me {q(uia) mandata tua n(on) su(m) oblit(us)}| q(uia) . oblit(us) should go here7 8 <E>rravi sic(ut) ovis quæ p(er)iit quære servu(m) tuu(m) d(omi)ne 78| d(omi)ne not in Vulgate Psalm 119 Psalm 119 /Canticum graduum\| 4 th line of marginal notes: T(itulus) <A>d d(omi)n(u)m cu(m)| Canticu(m) graduu(m). tribularer clamavi et exaudivit me {dolosa}| dolosa should go here1 <D>(omi)ne lib(er)a a(ni)ma(m) mea(m) a labiis iniquis et a lingua 1| <Q>uid det(ur) t(ibi) aut q(ui)d apponat(ur) t(ibi) ad lingua(m) dolosa(m)| <S>agittæ potentis accutæ cu(m) carbonib(us) desolatorii/s\| <H>eu mihi q(uia) incolat(us) m(eu)s p(ro)longat(us) (est) habitavi cu(m)| habitantib(us) cedar multu(m) incola fuit a(ni)ma m(e)a | <C>u(m) his qui oderunt pace(m) era(m) pacific(us) cu(m) loq(ue)bar | illis impugnabant me gratis | Psalm 120 Psalm 120 <Canticum graduum> | <L>evavi oculos m(e)os in montes unde veniat | auxiliu(m) m(ihi) {qui custodit te} {isr(aë)l}| qui custodit te should go here1 <A>uxiliu(m) m(eu)m a d(omi)no qui fec(it) cælu(m) et t(er)ra(m)| isr(aë)l should go here2 <N>on det in co(m)motione(m) pede(m) tuu(m) neq(ue) dormitet 1| <E>cce n(on) dormitabit neq(ue) dormiet q(ui) custodit 2| <D>(omi)n(u)s custodit te d(omi)n(u)s p(ro)tectio tua sup(er) manu(m)| dext(er)a(m) tua(m) {tua(m) d(omi)n(u)s} {et usq(ue) in s(æ)c(u)l(u)m}| tua(m) d(omi)n(u)s should go here3 <P>er die(m) sol n(on) uret te neq(ue) luna p(er) nocte(m)| et usq(ue) in s(æ)c(u)l(u)m should 4 <D>(omi)n(u)s custodit te ab om(n)i malo custodiat a(ni)ma(m) 3| go here <D>(omi)n(u)s custodiat introitu(m) tuu(m) et exitu(m) tuu(m) ex h(oc) n(un)c 4| The Glossed Psalter (90v) Psalm 121 Psalm 121 <Canticum graduum huic David> | <L>ætatus su(m) in his quæ dicta s(un)t m(ihi) in domu(m) | d(omi)ni ibim(us) {cipatio ei(us) in idipsu(m)}| cipatio . -

For Those Not Attending an In-Person Service We Will Have

For those not attending an in-person service we will have first listened to the official lyric video of Toby Mac’s song “Keep Walking.” You can find it and also see concert performances of the song on YouTube. Psalms of Ascent – Journey On Surrounded (Psalms 125-126) Perhaps you are familiar with this quote from Max Lucado, “Thanks to Christ, this earth can be the nearest you come to hell. But apart from Christ, this earth is the nearest you come to heaven.” God’s calling on believers is a one-way journey. Paul wrote in Philippians 3:14, “I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus.” The Psalms of Ascent were sung to remind Jewish pilgrims of their relationship with God. To keep their heads and hearts anchored in their heavenly home, their true home. But sometimes not even Jerusalem, the city of their God, was “near enough.” For us too. Sometimes “hell” feels far too near. Disillusionment and the loss of hope are real. Workplace conflicts, mental health tragedies associated COVID-19, increased drug and alcohol abuse and suicide, and stressed family relationships. As Israel was often a defeated, occupied nation, singing, “Those who trust in the Lord are as secure as Mount Zion; they will not be defeated but will endure forever…” did not mix with reality. Perhaps your reality doesn’t gel with this passage either. A couple of weeks ago I pointed out that in the time of Jesus, in spite of the fact that men eighteen years and older were commanded to make the journey up to Jerusalem three times a year (Exodus 23:14-17, 34:18-23), for all intents and practices, these pilgrimages had become “optional.” Jewish history contains stories of pilgrims beginning and turning around.