Downloaded 24/02/2015 - 73920 Entries) Digested with Trypsin/P Was Used As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Low-Coverage Exome Sequencing Screen in Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Tumors Reveals Evidence of Exposure to Carcinogenic Aristolochic Acid

Published OnlineFirst September 17, 2015; DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0553 Research Article Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers Low-Coverage Exome Sequencing Screen in & Prevention Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Tumors Reveals Evidence of Exposure to Carcinogenic Aristolochic Acid Xavier Castells1, Sandra Karanovic2, Maude Ardin1, Karla Tomic3, Evanguelos Xylinas4, Geoffroy Durand5, Stephanie Villar1, Nathalie Forey5, Florence Le Calvez-Kelm5, Catherine Voegele5,Kresimir Karlovic3, Maja Misic3, Damir Dittrich3, Igor Dolgalev6, James McKay5, Shahrokh F. Shariat4, Viktoria S. Sidorenko7, Andrea Fernandes7, Adriana Heguy6, Kathleen G. Dickman7,8, Magali Olivier1, Arthur P. Grollman7,8, Bojan Jelakovic2, and Jiri Zavadil1 Abstract Background: Dietary exposure to cytotoxic and carcinogenic 10Â. Analysis at 3 to 9Â coverage revealed the signature in aristolochic acid (AA) causes severe nephropathy typically asso- 91% of the positive samples. The exome-wide distribution of the ciated with urologic cancers. Monitoring of AA exposure uses predominant A>T transversions exhibited a stochastic pattern, biomarkers such as aristolactam-DNA adducts, detected by mass whereas 83 cancer driver genes were enriched for recurrent non- spectrometry in the kidney cortex, or the somatic A>T transversion synonymous A>T mutations. In two patients, pairs of tumors pattern characteristic of exposure to AA, as revealed by previous from different parts of the urinary tract, including the bladder, DNA-sequencing studies using fresh-frozen tumors. harbored overlapping mutation patterns, suggesting tumor dis- Methods: Here, we report a low-coverage whole-exome semination via cell seeding. sequencing method (LC-WES) optimized for multisample detec- Conclusions: LC-WES analysis of archived tumor tissues is a tion of the AA mutational signature, and demonstrate its utility in reliable method applicable to investigations of both the exposure 17 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded urothelial tumors obtained to AA and its biologic effects in human carcinomas. -

Characterization of Dysregulated Lncrna-Mrna Network Based on Cerna Hypothesis to Reveal the Occurrence and Recurrence of Myocar

Zhang et al. Cell Death Discovery (2018) 4:35 DOI 10.1038/s41420-018-0036-7 Cell Death Discovery ARTICLE Open Access Characterization of dysregulated lncRNA- mRNA network based on ceRNA hypothesis to reveal the occurrence and recurrence of myocardial infarction Guangde Zhang1,HaoranSun2, Yawei Zhang2, Hengqiang Zhao2, Wenjing Fan1,JianfeiLi3,YingliLv2, Qiong Song2, Jiayao Li2,MingyuZhang1 and Hongbo Shi2 Abstract Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) acting as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) play important roles in initiation and development of human diseases. However, the mechanism of ceRNA regulated by lncRNA in myocardial infarction (MI) remained unclear. In this study, we performed a multi-step computational method to construct dysregulated lncRNA-mRNA networks for MI occurrence (DLMN_MI_OC) and recurrence (DLMN_MI_Re) based on “ceRNA hypothesis”. We systematically integrated lncRNA and mRNA expression profiles and miRNA-target regulatory interactions. The constructed DLMN_MI_OC and DLMN_MI_Re both exhibited biological network characteristics, and functional analysis demonstrated that the networks were specific for MI. Additionally, we identified some lncRNA-mRNA ceRNA modules involved in MI occurrence and recurrence. Finally, two new panel biomarkers defined by four lncRNAs (RP1-239B22.5, AC135048.13, RP11-4O1.2, RP11-285F7.2) from 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; DLMN_MI_OC and three lncRNAs (RP11-363E7.4, CTA-29F11.1, RP5-894A10.6) from DLMN_MI_Re with high classification performance were, respectively, identified in distinguishing controls from patients, and patients with recurrent events from those without recurrent events. This study will provide us new insight into ceRNA-mediated regulatory mechanisms involved in MI occurrence and recurrence, and facilitate the discovery of candidate diagnostic and prognosis biomarkers for MI. -

Supplementary File 2A Revised

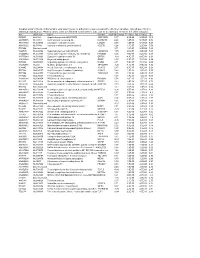

Supplementary file 2A. Differentially expressed genes in aldosteronomas compared to all other samples, ranked according to statistical significance. Missing values were not allowed in aldosteronomas, but to a maximum of five in the other samples. Acc UGCluster Name Symbol log Fold Change P - Value Adj. P-Value B R99527 Hs.8162 Hypothetical protein MGC39372 MGC39372 2,17 6,3E-09 5,1E-05 10,2 AA398335 Hs.10414 Kelch domain containing 8A KLHDC8A 2,26 1,2E-08 5,1E-05 9,56 AA441933 Hs.519075 Leiomodin 1 (smooth muscle) LMOD1 2,33 1,3E-08 5,1E-05 9,54 AA630120 Hs.78781 Vascular endothelial growth factor B VEGFB 1,24 1,1E-07 2,9E-04 7,59 R07846 Data not found 3,71 1,2E-07 2,9E-04 7,49 W92795 Hs.434386 Hypothetical protein LOC201229 LOC201229 1,55 2,0E-07 4,0E-04 7,03 AA454564 Hs.323396 Family with sequence similarity 54, member B FAM54B 1,25 3,0E-07 5,2E-04 6,65 AA775249 Hs.513633 G protein-coupled receptor 56 GPR56 -1,63 4,3E-07 6,4E-04 6,33 AA012822 Hs.713814 Oxysterol bining protein OSBP 1,35 5,3E-07 7,1E-04 6,14 R45592 Hs.655271 Regulating synaptic membrane exocytosis 2 RIMS2 2,51 5,9E-07 7,1E-04 6,04 AA282936 Hs.240 M-phase phosphoprotein 1 MPHOSPH -1,40 8,1E-07 8,9E-04 5,74 N34945 Hs.234898 Acetyl-Coenzyme A carboxylase beta ACACB 0,87 9,7E-07 9,8E-04 5,58 R07322 Hs.464137 Acyl-Coenzyme A oxidase 1, palmitoyl ACOX1 0,82 1,3E-06 1,2E-03 5,35 R77144 Hs.488835 Transmembrane protein 120A TMEM120A 1,55 1,7E-06 1,4E-03 5,07 H68542 Hs.420009 Transcribed locus 1,07 1,7E-06 1,4E-03 5,06 AA410184 Hs.696454 PBX/knotted 1 homeobox 2 PKNOX2 1,78 2,0E-06 -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature Into Vascularized Glomeruli Upon Experimental Transplantation

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature into Vascularized Glomeruli upon Experimental Transplantation † Sazia Sharmin,* Atsuhiro Taguchi,* Yusuke Kaku,* Yasuhiro Yoshimura,* Tomoko Ohmori,* ‡ † ‡ Tetsushi Sakuma, Masashi Mukoyama, Takashi Yamamoto, Hidetake Kurihara,§ and | Ryuichi Nishinakamura* *Department of Kidney Development, Institute of Molecular Embryology and Genetics, and †Department of Nephrology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan; ‡Department of Mathematical and Life Sciences, Graduate School of Science, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan; §Division of Anatomy, Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan; and |Japan Science and Technology Agency, CREST, Kumamoto, Japan ABSTRACT Glomerular podocytes express proteins, such as nephrin, that constitute the slit diaphragm, thereby contributing to the filtration process in the kidney. Glomerular development has been analyzed mainly in mice, whereas analysis of human kidney development has been minimal because of limited access to embryonic kidneys. We previously reported the induction of three-dimensional primordial glomeruli from human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Here, using transcription activator–like effector nuclease-mediated homologous recombination, we generated human iPS cell lines that express green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the NPHS1 locus, which encodes nephrin, and we show that GFP expression facilitated accurate visualization of nephrin-positive podocyte formation in -

SUMO and Transcriptional Regulation: the Lessons of Large-Scale Proteomic, Modifomic and Genomic Studies

molecules Review SUMO and Transcriptional Regulation: The Lessons of Large-Scale Proteomic, Modifomic and Genomic Studies Mathias Boulanger 1,2 , Mehuli Chakraborty 1,2, Denis Tempé 1,2, Marc Piechaczyk 1,2,* and Guillaume Bossis 1,2,* 1 Institut de Génétique Moléculaire de Montpellier (IGMM), University of Montpellier, CNRS, Montpellier, France; [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (D.T.) 2 Equipe Labellisée Ligue Contre le Cancer, Paris, France * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.P.); [email protected] (G.B.) Abstract: One major role of the eukaryotic peptidic post-translational modifier SUMO in the cell is transcriptional control. This occurs via modification of virtually all classes of transcriptional actors, which include transcription factors, transcriptional coregulators, diverse chromatin components, as well as Pol I-, Pol II- and Pol III transcriptional machineries and their regulators. For many years, the role of SUMOylation has essentially been studied on individual proteins, or small groups of proteins, principally dealing with Pol II-mediated transcription. This provided only a fragmentary view of how SUMOylation controls transcription. The recent advent of large-scale proteomic, modifomic and genomic studies has however considerably refined our perception of the part played by SUMO in gene expression control. We review here these developments and the new concepts they are at the origin of, together with the limitations of our knowledge. How they illuminate the SUMO-dependent Citation: Boulanger, M.; transcriptional mechanisms that have been characterized thus far and how they impact our view of Chakraborty, M.; Tempé, D.; SUMO-dependent chromatin organization are also considered. -

SUMO Proteins in the Cardiovascular System: Friend Or Foe? Prithviraj Manohar Vijaya Shetty1,2, Ashraf Yusuf Rangrez1,3* and Norbert Frey1,3*

Shetty et al. J Biomed Sci (2020) 27:98 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-020-00689-0 REVIEW Open Access SUMO proteins in the cardiovascular system: friend or foe? Prithviraj Manohar Vijaya Shetty1,2, Ashraf Yusuf Rangrez1,3* and Norbert Frey1,3* Abstract Post-translational modifcations (PTMs) are crucial for the adaptation of various signalling pathways to ensure cellular homeostasis and proper adaptation to stress. PTM is a covalent addition of a small chemical functional group such as a phosphate group (phosphorylation), methyl group (methylation), or acetyl group (acetylation); lipids like hydropho- bic isoprene polymers (isoprenylation); sugars such as a glycosyl group (glycosylation); or even small peptides such as ubiquitin (ubiquitination), SUMO (SUMOylation), NEDD8 (neddylation), etc. SUMO modifcation changes the function and/or fate of the protein especially under stress conditions, and the consequences of this conjugation can be appre- ciated from development to diverse disease processes. The impact of SUMOylation in disease has not been monoto- nous, rather SUMO is found playing a role on both sides of the coin either facilitating or impeding disease progression. Several recent studies have implicated SUMO proteins as key regulators in various cardiovascular disorders. The focus of this review is thus to summarize the current knowledge on the role of the SUMO family in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases. Keywords: Post-translational modifcation, SUMO, SUMOylation, Cardiovascular diseases Introduction or could be brought about by the state at which the cell is Every cell has countless biological processes occurring at that instant, e.g. in a situation of cellular stress. simultaneously, right from its genesis till its terminus, Small Ubiquitin like Modifer (SUMO) proteins have recalibrating its fate perpetually. -

Supplementary Material Contents

Supplementary Material Contents Immune modulating proteins identified from exosomal samples.....................................................................2 Figure S1: Overlap between exosomal and soluble proteomes.................................................................................... 4 Bacterial strains:..............................................................................................................................................4 Figure S2: Variability between subjects of effects of exosomes on BL21-lux growth.................................................... 5 Figure S3: Early effects of exosomes on growth of BL21 E. coli .................................................................................... 5 Figure S4: Exosomal Lysis............................................................................................................................................ 6 Figure S5: Effect of pH on exosomal action.................................................................................................................. 7 Figure S6: Effect of exosomes on growth of UPEC (pH = 6.5) suspended in exosome-depleted urine supernatant ....... 8 Effective exosomal concentration....................................................................................................................8 Figure S7: Sample constitution for luminometry experiments..................................................................................... 8 Figure S8: Determining effective concentration ......................................................................................................... -

E-Mutpath: Computational Modelling Reveals the Functional Landscape of Genetic Mutations Rewiring Interactome Networks

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.22.262386; this version posted August 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. e-MutPath: Computational modelling reveals the functional landscape of genetic mutations rewiring interactome networks Yongsheng Li1, Daniel J. McGrail1, Brandon Burgman2,3, S. Stephen Yi2,3,4,5 and Nidhi Sahni1,6,7,8,* 1Department oF Systems Biology, The University oF Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA 2Department oF Oncology, Livestrong Cancer Institutes, Dell Medical School, The University oF Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 3Institute For Cellular and Molecular Biology (ICMB), The University oF Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 4Institute For Computational Engineering and Sciences (ICES), The University oF Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 5Department oF Biomedical Engineering, Cockrell School of Engineering, The University oF Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 6Department oF Epigenetics and Molecular Carcinogenesis, The University oF Texas MD Anderson Science Park, Smithville, TX 78957, USA 7Department oF BioinFormatics and Computational Biology, The University oF Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA 8Program in Quantitative and Computational Biosciences (QCB), Baylor College oF Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA *To whom correspondence should be addressed. Nidhi Sahni. Tel: +1 512 2379506; Email: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.22.262386; this version posted August 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. -

Molecular Signatures Differentiate Immune States in Type 1 Diabetes Families

Page 1 of 65 Diabetes Molecular signatures differentiate immune states in Type 1 diabetes families Yi-Guang Chen1, Susanne M. Cabrera1, Shuang Jia1, Mary L. Kaldunski1, Joanna Kramer1, Sami Cheong2, Rhonda Geoffrey1, Mark F. Roethle1, Jeffrey E. Woodliff3, Carla J. Greenbaum4, Xujing Wang5, and Martin J. Hessner1 1The Max McGee National Research Center for Juvenile Diabetes, Children's Research Institute of Children's Hospital of Wisconsin, and Department of Pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin Milwaukee, WI 53226, USA. 2The Department of Mathematical Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI 53211, USA. 3Flow Cytometry & Cell Separation Facility, Bindley Bioscience Center, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA. 4Diabetes Research Program, Benaroya Research Institute, Seattle, WA, 98101, USA. 5Systems Biology Center, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20824, USA. Corresponding author: Martin J. Hessner, Ph.D., The Department of Pediatrics, The Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI 53226, USA Tel: 011-1-414-955-4496; Fax: 011-1-414-955-6663; E-mail: [email protected]. Running title: Innate Inflammation in T1D Families Word count: 3999 Number of Tables: 1 Number of Figures: 7 1 For Peer Review Only Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online April 23, 2014 Diabetes Page 2 of 65 ABSTRACT Mechanisms associated with Type 1 diabetes (T1D) development remain incompletely defined. Employing a sensitive array-based bioassay where patient plasma is used to induce transcriptional responses in healthy leukocytes, we previously reported disease-specific, partially IL-1 dependent, signatures associated with pre and recent onset (RO) T1D relative to unrelated healthy controls (uHC). -

Supplementary Table 2

Supplementary Table 2. Non-synonymous somatic mutations identified in the Discovery set of four NKTCL cases. Gene Sample Transcript Amino Mutation No. Nucleotide (Genomic) Symbol ID Accession ID Acid Type 1 ABCA4 7 CCDS747.1 g.chr1: 94564391 T>C p.T243A Missense 2 ACOX2 7 ENST00000492530 g.chr3: 58517538 C>T p.G7R Missense 3 ACSS3 10 CCDS9022.1 g.chr12: 81503369 C>A p.Y114X Nonsense 4 ADAMTS2 7 CCDS4444.1 g.chr5: 178540908 A>C p.I1199S Missense 5 AKAP8 7 CCDS12329.1 g.chr19: 15483121 C>T p.G300D Missense 6 ANGEL2 7 CCDS1512.1 g.chr1: 213168445 G>A p.P525S Missense 7 ANKZF1 59 CCDS42821.1 g.chr2: 220100475 C>T p.R617W Missense 8 APBA3 59 ENST00000439726 g.chr19: 3751342 insG fs Insertion 9 APLNR 7 CCDS7950.1 g.chr11: 57004458 A>T p.F7L Missense 10 ARMC7 7 CCDS11714.1 g.chr17: 73124795 G>A p.D87N Missense 11 ATM 7 CCDS31669.1 g.chr11: 108192038 G>A p.V2155M Missense 12 ATP6V0A1 7 CCDS45683.1 g.chr17: 40666340 A>T p.H762L Missense 13 BNIP3 7 CCDS7663.1 g.chr10: 133787372 C>T p.G41E Missense 14 BRCA1 10 CCDS11453.1 g.chr17: 41246517 G>A p.A344V Missense 15 BRI3 7 CCDS5656.1 g.chr7: 97911710 G>A p.V64I Missense 16 BSG 7 CCDS12032.1 g.chr19: 571548 A>G p.M1V Missense 17 BTAF1 7 CCDS7419.1 g.chr10: 93713569 A>G p.R214G Missense 18 BTBD11 59 CCDS31893.1 g.chr12: 107914407 G>A p.E427K Missense 19 BTN2A3 10 ENST00000465856 g.chr6: 26423337 G>A p.E86K Missense 20 C13orf23 31 CCDS45041.1 g.chr13: 39587665 delA fs Deletion 21 C2CD3 7 CCDS31636.1 g.chr11: 73753262 T>G p.S1833R Missense 22 C3orf63 31 CCDS46853.1 g.chr3: 56681175 A>C p.F530L Missense