Legeny, Viola (2018) Idioms in Scots. Mphil(R) Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Insights Into the Semantics of Legal Concepts and the Legal Dictionary

TERMINOLOGY and LEXICOGRAPHY B a j c i ´c RESEARCH and PRACTICE 17 and the Legal Dictionary Legal the and Martina Semantics of Legal Concepts Concepts Legal of Semantics New Insights into the the into Insights New John Benjamins Publishing Company Publishing Benjamins John New Insights into the Semantics of Legal Concepts and the Legal Dictionary Terminology and Lexicography Research and Practice (TLRP) issn 1388-8455 Terminology and Lexicography Research and Practice aims to provide in-depth studies and background information pertaining to Lexicography and Terminology. General works include philosophical, historical, theoretical, computational and cognitive approaches. Other works focus on structures for purpose- and domain-specific compilation (LSP), dictionary design, and training. The series includes monographs, state-of-the-art volumes and course books in the English language. For an overview of all books published in this series, please see www.benjamins.com/catalog/tlrp Editors Marie-Claude L’ Homme Kyo Kageura University of Montreal University of Tokyo Volume 17 New Insights into the Semantics of Legal Concepts and the Legal Dictionary by Martina Bajčić New Insights into the Semantics of Legal Concepts and the Legal Dictionary Martina Bajčić University of Rijeka John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 the American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. doi 10.1075/tlrp.17 Cataloging-in-Publication Data available from Library of Congress: lccn 2016053197 (print) / 2016055071 (e-book) isbn 978 90 272 2341 8 (Hb) isbn 978 90 272 6600 2 (e-book) © 2017 – John Benjamins B.V. -

The Thinking of Speaking Issue #27 May /June 2017 Ccooggnnaatteess,, Tteelllliinngg Rreeaall Ffrroomm Ffaakkee More About Cognates Than You Ever Wanted to Know

Parrot Time The Thinking of Speaking Issue #27 May /June 2017 CCooggnnaatteess,, TTeelllliinngg RReeaall ffrroomm FFaakkee More about cognates than you ever wanted to know AA PPeeeekk iinnttoo PPiinnyyiinn The Romaniizatiion of Mandariin Chiinese IInnssppiirraattiioonnaall LLaanngguuaaggee AArrtt Maxiimiilliien Urfer''s piiece speaks to one of our wriiters TThhee LLeeaarrnniinngg MMiinnddsseett Language acquiisiitiion requiires more than study An Art Exhibition That Spoke To Me LLooookk bbeeyyoonndd wwhhaatt yyoouu kknnooww Parrot Time is your connection to languages, linguistics and culture from the Parleremo community. Expand your understanding. Never miss an issue. 2 Parrot Time | Issue#27 | May/June2017 Contents Parrot Time Parrot Time is a magazine covering language, linguistics Features and culture of the world around us. 8 More About Cognates Than You Ever Wanted to Know It is published by Scriveremo Languages interact with each other, sharing aspects of Publishing, a division of grammar, writing, and vocabulary. However, coincidences also Parleremo, the language learning create words which only looked related. John C. Rigdon takes a community. look at these true and false cognates, and more. Join Parleremo today. Learn a language, make friends, have fun. 1 6 A Peek into Pinyin Languages with non-Latin alphabets are often a major concern for language learners. The process of converting a non-Latin alphabet into something familiar is called "Romanization", and Tarja Jolma looks at how this was done for Mandarin Chinese. 24 An Art Exhibition That Spoke To Me Editor: Erik Zidowecki Inspiration is all around us, often crossing mediums. Olivier Email: [email protected] Elzingre reveals how a performance piece affected his thinking of languages. -

Christopher Upton Phd Thesis

?@A374? 7; ?2<@@7?6 81@7; 2IQJRSOPIFQ 1$ APSON 1 @IFRJR ?TCMJSSFE GOQ SIF 3FHQFF OG =I3 BS SIF ANJUFQRJSX OG ?S$ 1NEQFVR '.-+ 5TLL MFSBEBSB GOQ SIJR JSFM JR BUBJLBCLF JN >FRFBQDI0?S1NEQFVR/5TLL@FWS BS/ ISSP/%%QFRFBQDI#QFPORJSOQX$RS#BNEQFVR$BD$TK% =LFBRF TRF SIJR JEFNSJGJFQ SO DJSF OQ LJNK SO SIJR JSFM/ ISSP/%%IEL$IBNELF$NFS%'&&()%(,)* @IJR JSFM JR PQOSFDSFE CX OQJHJNBL DOPXQJHIS STUDIES IN SCOTTISH LATIN by Christopher A. Upton Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews October 1984 ýýFCA ýý£ s'i ý`q. q DRE N.6 - Parentibus meis conjugique meae. Iý Christopher Allan Upton hereby certify that this thesis which is approximately 100,000 words in length has been written by men that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. ý.. 'C) : %6 date .... .... signature of candidat 1404100 I was admitted as a research student under Ordinance No. 12 on I October 1977 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph. D. on I October 1978; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 1977 and 1980. $'ý.... date . .. 0&0.9 0. signature of candidat I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate to the degree of Ph. D. of the University of St Andrews and that he is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Proceedings of the XVI EURALEX International Congress: the User in Focus 15-19 July 2014, Bolzano/Bozen

Proceedings of the XVI EURALEX International Congress: The User in Focus 15-19 July 2014, Bolzano/Bozen Edited by Andrea Abel, Chiara Vettori, Natascia Ralli Part 3 1 Proceedings of the XVI EURALEX International Congress: The User in Focus Index Part 1 Plenary Lectures 23 From Lexicography to Terminology: a Cline, not a Dichotomy .......................................................................................................................... 25 Thierry Fontenelle Natural Language Processing Techniques for Improved User-friendliness of Electronic Dictionaries 47 Ulrich Heid Using Mobile Bilingual Dictionaries in an EFL Class 63 Carla Marello Meanings, Ideologies, and Learners’ Dictionaries 85 Rosamund Moon The Dictionary-Making Process 107 The Making of a Large English-Arabic/Arabic-English Dictionary: the Oxford Arabic Dictionary 109 Tressy Arts Simple and Effective User Interface for the Dictionary Writing System 125 Kamil Barbierik, Zuzana Děngeová, Martina Holcová Habrová, Vladimír Jarý, Tomáš Liška, Michaela Lišková, Miroslav Virius Totalitarian Dictionary of Czech .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 137 František Čermák Dictionary of Abbreviations in Linguistics: Towards Defining Cognitive Aspects as Structural Elements of the Entry 145 Ivo Fabijancic´ La definizione delle relazioni intra- e interlinguistiche nella costruzione dell’ontologia -

11-20 November Issue

The British Isles Historic Society Heritage, History, Traditions & Customs 11-20 November Issue St. Andrew deeming himself unworthy to be crucified in the same manner as Jesus Christ. Instead, he was nailed St. Andrew has been celebrated upon an X-shaped cross on 30 November 60AD in in Scotland for over a thousand years, Greece, and thus the diagonal cross of the saltire with feasts being held in his honour as was adopted as his symbol, and the last day in far back as the year 1000 AD. November designated his saint day. However, it wasn’t until 1320, According to legend, Óengus II, king of Picts when Scotland’s independence was and Scots, led an army against the Angles, a declared with the signing of The Germanic people that invaded Britain. The Scots Declaration of Arbroath, that he officially became were heavily outnumbered, and Óengus prayed the Scotland’s patron saint. Since then St Andrew has night before battle, vowing to name St. Andrew the become tied up in so much of Scotland. The flag of patron saint of Scotland if they won. Scotland, the St. Andrew’s Cross, was chosen in honour of him. Also, the ancient town of St Andrews On the day of the battle, white clouds formed was named due to its claim of being the final resting an X in the sky. The clouds were thought to place of St. Andrew. represent the X-shaped cross where St. Andrew was crucified. The troops were inspired by the apparent According to Christian teachings, Saint Andrew divine intervention, and they came out victorious was one of Jesus Christ’s twelve disciples. -

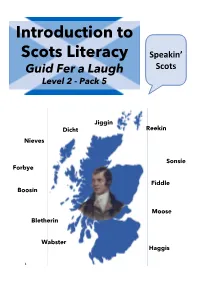

Introduction to Scots Literacy

Introduction to Scots Literacy Speakin’ Scots Guid Fer a Laugh Level 2 - Pack 5 Jiggin Dicht Reekin Nieves Sonsie Forbye Fiddle Boosin Moose Bletherin Wabster Haggis 1 Introduction to Guid Fer A Laugh We are part of the City of Edinburgh Council, South West Adult Learning team and usually deliver ‘Guid Fer a Laugh’ sessions for community groups in South West Edinburgh. Unfortunately, we are unable to meet groups due to Covid-19. Good news though, we have adapted some of the material and we hope you will join in at home. Development of Packs We plan to develop packs from beginner level 1 to 5. Participants will gradually increase in confidence and by level 5, should be able to: read, recognise, understand and write in Scots. Distribution during Covid-19 During Covid-19 restrictions we are emailing packs to community forums, organisations, groups and individuals. Using the packs The packs can be done in pairs, small groups or individually. They are being used by: families, carers, support workers and individuals. The activities are suitable for all adults but particularly those who do not have access to computer and internet. Adapting packs The packs can be adapted to suit participants’ needs. For example, the Pilmeny Development Project used The Scots Literacy Pack as part of a St Andrews Day Activity Pack which was posted out to 65 local older people. In the pack they included the Scots Literacy Pack 1 and 2, crosswords, shortbread and a blue pen. Please see photo. 2 The Aims of the Session – Whit’s it a’aboot? • it’s about learning Scots language and auld words • takes a look at Scots comedy, songs, poetry and writing • hae a guid laugh at ourselves and others Feedback fae folk This is pack number five and we move on a little to Level 2. -

Applying the CIDOC-CRM to Archaeological Grey Literature

Semantic Indexing via Knowledge Organization Systems: Applying the CIDOC-CRM to Archaeological Grey Literature Andreas Vlachidis A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Glamorgan / Prifysgol Morgannwg for the degree of a Doctor of Philosophy. July 2012 University of Glamorgan Faculty of Advanced Technology Certificate of Research This is to certify that, except where specific reference is made, the work presented in this thesis is the result of the investigation undertaken by the candidate. Candidate: ................................................................... Director of Studies: ..................................................... Declaration This is to certify that neither this thesis nor any part of it has been presented or is being currently submitted in candidature for any other degree other than the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Glamorgan. Candidate: ........................................................ Andreas Vlachidis PhD Thesis University of Glamorgan Abstract The volume of archaeological reports being produced since the introduction of PG161 has significantly increased, as a result of the increased volume of archaeological investigations conducted by academic and commercial archaeology. It is highly desirable to be able to search effectively within and across such reports in order to find information that promotes quality research. A potential dissemination of information via semantic technologies offers the opportunity to improve archaeological practice, -

Linguistic and Political Backlash and Conformity in Eighteenth-Century Scots

1 ‘An Eye for an Aye’: Linguistic and Political Backlash and Conformity in Eighteenth-Century Scots LING690 Sarah van Eyndhoven Abstract This study examines the effects of social and political changes that were occurring during the eighteenth century in Scotland on the use of written Scots, focussing in particular upon authors who were known to have been for or against the Union of the Parliaments in 1707. In order to capture a holistic representation of the levels of Scots in writing, I explore the proportion of Scots lexemes, compared with their corresponding English lexemes, in a purpose-built corpus containing a range of eighteenth-century texts. This corpus contains both texts that were produced by a general cross- section of Scottish society, and a number of politically-active individuals. I take a quantitative sociolinguistic approach to historical data by utilising statistical techniques that examine linguistic variation in a data-driven manner. This enables a more detailed and empirical exploration of Scots in the eighteenth century, which until now has been largely examined on a descriptive basis only. Using a number of statistical tools that are well suited to historical analyses, such as Variability-based Neighbour Clustering (Gries & Hilpert, 2008), conditional inference trees (Hothorn et al., 2006) and random forests (Breiman, 2001), I have been able to reconstruct both the general patterning of the Scots language over time and the extralinguistic factors encouraging or suppressing its presence in writing. In particular, I compare the use of Scots between the general literate population and political individuals active during this time period. I also explore the effect of the latter’s political sympathies on their language choices, and uncover several new and interesting effects conditioning the levels of Scots in their writings. -

Sib Folh Flews

jii^^; Sib Folh flews 5 R 09 5 3 2. S. t* | a cu 01 8 he Earl of Wessex leaving alter the Official Opening of the Orkney Library Tand Archive on Tuesday 2nd September 2003. In this lovely building Orkney Family history Society is to have its new office. J Contents:- V 2 From the Chair. Future Events 8 Rev. Alexander Smith 3 From the Editor. Deadlines. 10 Website information September meeting 11 Working on the Gardens' 4 The Long Road T)ome. Directory 12 Photographic history o! Flotta 5 Official opening of Orkney Library 13 October meeting & Archive 15 ftiuiualTHeal 6 Booh Review 16 Research via the Internet Quiz 19 Robert Snhster r From the Chair Seven years later my successor has been found! At the moment I am enjoying reading yet another new Orkney Book that has ap- At the last committee meeting Anne Ren- peared in time for Christmas. It is "'The dall was appointed Vice-Chairman and Shore' and roond aboot" written by the accepted the post with the knowledge that retired Orkney Librarian, David Tinch. she would soon be Chairman. This is a In it he describes growing up in Kirk- popular appointment Anne has taken an wall in the thirties and forties and all in active part in the running of the society a very humorous style. It contains in- from the early days. Among other things teresting photographs including school she has transcribed censuses, is working groups and a major bonus is the forty- on the Old Parish Registers and looks three prints of his stunning oil paint- after the office most Saturday afternoons. -

Man-Aided Computer, Translation from English

Conference Internationale sur le traitement Automatique des Langues. MANTAIDED COMPUTER TRANSLATION PROM ENGLISH INT0 FRENCH USING AN ON-LINE SYSTEM TO F~NIPULATE A BI-LINGUAL CONCEPTUAL DICTIONARY, OR THESAURUS. Author: MARGARET MASTERMAN Cambridge Language Research Unit, 20, Millington Road, CAMBRIDGE. ENGLAND. Conference Internationals sur le traitement Author: Margaret Masterman Institute: Cambridge Language Research Unit, 20, Milllngton Road, CAMBRIDGE, ENGLAND. Title: MAN-AIDED COMPUTER TRANSLATION FROM ENGLISH INT0 FRENCH USING AN ON-LINE SYSTEM TO MANIPULATE Work supported by: Canadian National Research Council. Office of Naval Research, Washington, D.C. background basic research @arlier supported by: National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. Air Force Office of Scientific Research, Washington, D.C. Office of Scientific andTechnical Information, State House, High Holborn, London. ~.B, References will be denoted thus: ~D~ I. Long-term querying of the current state of despondenc~ with regard to the prospects of Mechanics1 Translation. The immediate effect of the recently issued Report on Computers inTranslation and L~istics. LANGUAGE ~ MACHINES ~J3 has been to spread the view that there is no future at all for research in Mechanical Translation as such; a view which contrasts sharply with the earlier, euphoric view that (now that disc-files provide computers with indefinitely large memory-systems which can be quickly searched by random-access procedures) the Mechanical Translation research problem was all but "solved". It is possible, however, that this second, ultra- despondent view is as exaggerated as the first one was; all the more so as the~ is written from a very narrow research background without iny indication of this narrowness being ~iven. -

Britishness and Problems of Authenticity in Post-Union Literature from Addison to Macpherson

"Where are the originals?" Britishness and problems of authenticity in post-Union literature from Addison to Macpherson. Melvin Eugene Kersey III Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University of Leeds, School of English September 2001 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his/her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the generous help, encouragement and support of many people. My research has benefited beyond reckoning from the supervision of Professor David Fairer, whose inspired scholarship has never interfered with his commitment to my research. It is difficult to know whether to thank or to curse Professor Andrew Wawn for introducing me to James Macpherson's Ossianic poetry during my MA at Leeds, but at any rate I am now doubly indebted to him for his insightful reading of a chapter of this thesis. I am also grateful to Professor Paul Hammond for his enormously helpful comments and suggestions on another chapter. And despite the necessary professional distance which an internal examiner must maintain, I have still enjoyed the benevolent proximity effect of Professor Edward Larrissy. I am grateful to Sue Baker and the administrative staff of the School of English for providing me with employment and moral support during this thesis, especially Pamela Rhodes. Special thanks to the inestimable help, friendship and rigorous mind of Dr. Michael Brown, and to Professor Terence and Sue Brown for their repeated generous hospitality in Dublin. -

Informational Retrieval Thesaurus of Yaroslav Mudryi National Library of Ukraine: Content, Structure, and Use

Informational Retrieval Thesaurus of Yaroslav Mudryi National Library of Ukraine: Content, Structure, and Use Oksana Zbanatskaа, Oksana Turb and Ksenia Sizovab a National Academy of Managerial Staff of Culture and Arts, Lavrska str., 9, bldg. 15, Kyiv, 01015, Ukraine b Kremenchuk Mykhailo Ostrohradskyi National University, Pershotravneva str., 20, bldg. 3, Kremenchuk, 39600, Ukraine Abstract The paper deals with terminological and species content of the Yaroslav Mudryi National Library of Ukraine information retrieval thesaurus; its structure is characterized; examples of dictionary entries are given. For clarity, the dynamics of thesaurus filling is shown. A historical digression on the origin of term “thesaurus” is implemented. Keywords 1 Informational retrieval thesaurus (IRT), Automated information library systems (AILS), Descriptor, Non-descriptor, Document content, Yaroslav Mudryi National Library of Ukraine. 1. Introduction In Ukraine, as well as all over the world, information is one of critical and importance strategic resource and a driving factor for the further state development. Library is one of the main institutions that provide collection, organization and public use of information. A priority of the Yaroslav Mudryi National Library of Ukraine (Yaroslav Mudryi NLU) is to help users navigate the large information space, and quickly search for and access the necessary information resources, and ensure guarantee the constitutional rights of individuals, such as the right to information. In order to successfully solve this problem, library subject specialists who are experts in finding the best information created the first Ukrainian-language universal information retrieval thesaurus (IRT), designed to display the content of documents and user requests for further search in automated information library systems (AILS).