Luxembourg Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spaces and Identities in Border Regions

Christian Wille, Rachel Reckinger, Sonja Kmec, Markus Hesse (eds.) Spaces and Identities in Border Regions Culture and Social Practice Christian Wille, Rachel Reckinger, Sonja Kmec, Markus Hesse (eds.) Spaces and Identities in Border Regions Politics – Media – Subjects Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Natio- nalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de © 2015 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or uti- lized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover layout: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Cover illustration: misterQM / photocase.de English translation: Matthias Müller, müller translations (in collaboration with Jigme Balasidis) Typeset by Mark-Sebastian Schneider, Bielefeld Printed in Germany Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-2650-6 PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-2650-0 Content 1. Exploring Constructions of Space and Identity in Border Regions (Christian Wille and Rachel Reckinger) | 9 2. Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to Borders, Spaces and Identities | 15 2.1 Establishing, Crossing and Expanding Borders (Martin Doll and Johanna M. Gelberg) | 15 2.2 Spaces: Approaches and Perspectives of Investigation (Christian Wille and Markus Hesse) | 25 2.3 Processes of (Self)Identification(Sonja Kmec and Rachel Reckinger) | 36 2.4 Methodology and Situative Interdisciplinarity (Christian Wille) | 44 2.5 References | 63 3. Space and Identity Constructions Through Institutional Practices | 73 3.1 Policies and Normalizations | 73 3.2 On the Construction of Spaces of Im-/Morality. -

Bibliographie Courante De La Littérature Luxembourgeoise 2010

GRAND-DUCHÉ DE LUXEMBOURG MINISTÈRE DE LA CULTURE Daphné BOEHLES Bibliographie courante de la littérature luxembourgeoise BIBLIOGRAPHIE LITTÉRAIRE 2010 2010 (23e année) et compléments des années précédentes 2011 CENTRE NATIONAL DE LITTÉRATURE CENTRE NATIONAL DE LITTÉRATURE BIBLIOGRAPHIE LITTÉRAIRE 2010 Bibliographie courante de la littérature luxembourgeoise 2010 1 Impressum: Editeur: Centre national de littérature 2, rue E. Servais L-7565 Mersch 2011 Tirage: 600 exemplaires Imprimerie: Hengen ISSN 1016-328X 2 MINISTÈRE DE LA CULTURE Daphné BOEHLES Bibliographie courante de la littérature luxembourgeoise 2010 (23e année) et compléments des années précédentes CENTRE NATIONAL DE LITTÉRATURE MERSCH 2011 3 Sommaire Avant-propos p. 7 Photographies et abréviations p. 8 1 Linguistique et politique linguistique p. 9 2 Anthologies, bibliographies et ouvrages de référence p. 26 3 Histoire et critique p. 32 3-1 Essais et articles généraux p. 32 3-2 Auteurs luxembourgeois p. 45 3-3 Auteurs étrangers p. 59 4 Littérature d’expression luxembourgeoise p. 140 4-1 Livres p. 140 4-2 Contributions p. 143 4-3 Critiques p. 152 5 Littérature d’expression française p. 160 5-1 Livres p. 160 5-2 Contributions p. 169 5-3 Critiques p. 183 6 Littérature d’expression allemande p. 192 6-1 Livres p. 192 6-2 Contributions p. 203 6-3 Critiques p. 226 7 Littérature d’expression diverse p. 242 7-1 Livres p. 242 7-2 Contributions p. 253 7-3 Critiques p. 260 8 Traductions p. 268 8-1 Traductions par des auteurs luxembourgeois p. 268 8-2 Traductions d’auteurs luxembourgeois p. 268 9 Cabaret et théâtre p. -

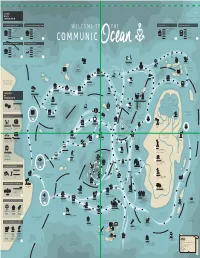

51% 49% 71% 16% 16%

THE WAY WE USE MERKUR - INF OGRAPHIC - C OMMUNICOCEAN - MA Y/JUNE 2015 COMMUNICATION USE OF DAILY NEWSPAPERS (TOP 5) USE OF WEEKLY & BI MONTHLY MAGAZINES (TOP 5) USE OF TV-STATIONS USE OF WEB-SITES (TOP 5) 39,0% LUXEMBURGER WORT 32,8% AUTOTOURING 25,2% RTL TELE LETZEBUERG 25,7% RTL.LU 29,5% L´ESSENTIEL 14,3% AUTO REVUE 3,8% NORDLIICHT TV 16,9% WORT.LU 9,3% TAGEBLATT 13,9% AUTOMOTO 2,1% CHAMBER TV 11,3% L´ESSENTIEL.LU 5,7% LE QUOTIDIEN 11,3% PAPERJAM ... ... 9,2% PUBLIC.LU 2,1% LETZEBUERGER JOURNAL 9,6% CITY MAG ... ... 4,7% TAGEBLATT.LU USE OF MONTHLY MAGAZINES (TOP 5) USE OF RADIO-SATIONS (TOP 5) 23,0% TÉLÉCRAN 36,8% RTL RADIO LETZEBUERG 17,0% LUX-POST WEEK-END 19,6% ELDORADIO 15,7% REVUE 8,5% RTL (GERMAN LANGUAGE) 12,1% CONTACTO 5,4% RADIO LATINA 7,7% LUXBAZAR 4,5% RADIO 100,7 NEW IDEA PRINT MEDIA STORY TELLING 2010s - PRINT NATIVE IN DANGER ADVERTISING MESSENGERS SEA OF PRINT CREATIVITY TRENDY COAST TEXTUAL C ONTENT FRESH IDEAS ISLANDS BUSINESS PLAN FREE NEW SPAPER INFOGRAPHICS 2007 - 1st ISSUE OF L’ESSENTIEL BIG BUDGET FEE / DUTY MAGAZINE MESSENGERS DATA 1932 - 1st MA GAZINE VISUALIZATION CONTINENT AUTOTOURING BY CONSEIL DE AUTOMOBILE CLUB PRESSE M PICTURES A NEWSPAPER I 1848 - 1st ISSUE OF N PRINTING NEWSPAPER RACING PIGE ON LUXEMBURGER WORT S THE HISTORY 1900s - 1st ME CHANIC 1913 - 1st ISSUE 776 B.C. - WINNER LIST COMPUTER PRINTER OF TAGEBLATT LOW BUDGET T OF OF OLYMPIC GAMES SENT R COMMUNICATION BY DOVES E AGE A LANGUAGE B ARRIER REEF NATIO- M NALITY 70,5% LUXEMBOURGISH N E W S P A P E R 55,7% FRENCH GENDER PROF- A REVOLUTION BEGAN 1650 - 1st DAILY 30,6% GERMAN ESSION AS MANKIND STARTED NEWSPAPER 21,0% ENGLISH TO BIND MESSAGES 20,0% PORTUGUESE TO TIME & TO SPACE BIG BUDGET CONSEIL DE HOBBIES PUBLICITÉ INCOME EDU- CLIENTS FUN CATION COAST HOW DID THEY DO THIS ? PRINT R OUTE REPRODUCTION CLIENTS 1450 - GUTENBER G EMOTIONS BUDGET INVENTS PRINT LETTERS COAST CONFUSION TELEVISION TRIANGLE TIME BINDING DEFINITION 1970 - ST ART OF TV-SPOT VISUAL 30.000 B.C. -

Rédacteurs En Chef De La Presse Luxembourgeoise 93

Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Agenda Plurionet Frank THINNES boulevard Royal 51 L-2449 Luxembourg +352 46 49 46-1 [email protected] www.plurio.net agendalux.lu BP 1001 L-1010 Luxembourg +352 42 82 82-32 [email protected] www.agendalux.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Hebdomadaires d'Lëtzeburger Land M. Romain HILGERT BP 2083 L-1020 Luxembourg +352 48 57 57-1 [email protected] www.land.lu Woxx M. Richard GRAF avenue de la Liberté 51 L-1931 Luxembourg +352 29 79 99-0 [email protected] www.woxx.lu Contacto M. José Luis CORREIA rue Christophe Plantin 2 L-2988 Luxembourg +352 4993-315 [email protected] www.contacto.lu Télécran M. Claude FRANCOIS BP 1008 L-1010 Luxembourg +352 4993-500 [email protected] www.telecran.lu Revue M. Laurent GRAAFF rue Dicks 2 L-1417 Luxembourg +352 49 81 81-1 [email protected] www.revue.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Correio Mme Alexandra SERRANO ARAUJO rue Emile Mark 51 L-4620 DIfferdange +352 444433-1 [email protected] www.correio.lu Le Jeudi M. Jacques HILLION rue du Canal 44 L-4050 Esch-sur-Alzette +352 22 05 50 [email protected] www.le-jeudi.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Quotidiens Zeitung vum Lëtzebuerger Vollek M. Ali RUCKERT - MEISER rue Zénon Bernard 3 L-4030 Esch-sur-Alzette +352 446066-1 [email protected] www.zlv.lu Le Quotidien M. -

National Distribution Lists of Media for the "Help" Campaign

LUXEMBOURG Nom du Mediaatt05072611563078719EA79657.xls Rédacteur en chef Ville Presse quotidienne Letzeburger Journal Claude Karger Luxembourg Letzeburger Journal Colette Mart Luxembourg La Voix du Luxembourg Laurent Moyse Luxembourg Le Quotidien Denis Berche Esch-sur-Alzette Luxemburger Wort Léon Zeches / Jean Louis scheffen Luxembourg Tageblatt Alvin Sold/Romain Durlier Esch-sur-Alzette Zeitung vum Letzebuerger Vollek Ali Ruckert Luxembourg Presse Hebdomadaire Contacto José Correia Luxembourg Correio José Dias Luxembourg d'Letzeburger Land Mario Hirsch Luxembourg Le Jeudi Jacques Hillion Esch-sur-Alzette Revue Stefan Kunzmann Luxembourg Revue Claude Wolf Luxembourg Télécran Roland Arens Luxembourg Télécran Martine Folscheid Luxembourg Télécran Britta Schlueter Luxembourg Woxx Robert Garcia Luxembourg Presse Mensuelle Agefi Luxembourg Olivier Minguet Capellen Femmes Magazine Maria Pietrangelli Luxembourg Le Monde Diplomatique Francis Wagner Esch-sur-Alzette Nico Mike Koedinger Luxembourg paperJam Jean Michel Gaudron Luxembourg paperJam Francis Gasparotto Luxembourg paperJam Ludivine Plessy Luxembourg paperJam Florence Reinson Luxembourg RADIO DNR Isabelle Decker Luxembourg DNR Radio Jean-Marc Sturm Luxembourg Eldoradio Isabel Galiano / ivano Andressini Luxembourg Radio ARA Radio Latina Gomes Avelinos Luxembourg Radio socio-culturelle 100,7 Fernand Weides Luxembourg RTL Radio Letzebuerg Marc Linster Luxembourg Radio Latina Gomes Avelinos Luxembourg Radio Latina Serge Ferreira Luxembourg TELEVISION att05072611563078719EA79657.xls TTV Daniel -

Décision N° 2009-FO-01 Du 2 Juillet 2009 Concernant Une Procédure Au Fond Relativement À A) Une Plainte Pour Violation Du Droit De La Concurrence Déposée Par 1) M

Décision N° 2009-FO-01 du 2 juillet 2009 concernant une procédure au fond relativement à a) une plainte pour violation du droit de la concurrence déposée par 1) M. Jean NICOLAS, demeurant à L-8391 Nospelt, 2, rue de Roodt, pris en sa qualité d’éditeur responsable des produits de presse « L’Investigateur », « Lëtzebuerg Privat » et « Promi » 2) la S.A. LUXEDIPRESSE, établie et ayant son siège social à L-8391 Nospelt, 2, rue de Roodt, producteur des produits de presse francophones du « Groupe de presse Nicolas », et notamment de l’hebdomadaire « L’Investigateur » 3) la S.A. SCOOP, établie et ayant son siège social à L-8391 Nospelt, 2, rue de Roodt, productrice des émissions de télévision du « Groupe de presse Nicolas » 4) la S.A. PRIVATLUXPROD, établie et ayant son siège social à L-8391 Nospelt, 2, rue de Roodt, producteur des produits de presse germanophones du « Groupe de presse Nicolas », et notamment de l’hebdomadaire « Lëtzebuerg Privat » et du bimensuel « Promi » mettant en cause 1) la S.A. EDITA, établie et ayant son siège social à L-4620 Differdange, 51, rue Emile Mark, inscrite au Registre de commerce et des sociétés sous le N° B129294 2) la S.A. EDITPRESS LUXEMBOURG, établie et ayant son siège social à L- 4050 Esch-sur-Alzette, 44, rue du Canal, inscrite au Registre de commerce et des sociétés sous le N° B5407 3) la société de droit suisse A.G. TAMEDIA, établie et ayant son siège social à CH-8004 Zürich, 21, Werdstrasse b) une auto-saisine par l’Inspection de la concurrence pour violation du droit de la concurrence, mettant en cause la S.A. -

Country Media Point Media Type

Country Media Point Media Type Austria satzKONTOR Blog Austria A1 Telekom Austria AG Company/Organisation Austria Accedo Austria GmbH Company/Organisation Austria Agentur für Monopolverwaltung Company/Organisation Austria AGES – Agentur für Ernährungssicherheit Company/Organisation Austria AGGM – Austrian Gas Grid Management GmbHCompany/Organisation Austria Agrana AG Company/Organisation Austria Agrarmarkt Austria Company/Organisation Austria AHHV Verlags GmbH Company/Organisation Austria Aidshilfe Salzburg Company/Organisation Austria Air Liquide Company/Organisation Austria AIZ - Agrarisches Informationszentrum Company/Organisation Austria AKH – Allgemeines Krankenhaus der Stadt WienCompany/Organisation Austria Albatros Media GmbH Company/Organisation Austria Albertina Company/Organisation Austria Alcatel Lucent Austria AG Company/Organisation Austria Allgemeine Baugesellschaft A. Porr AG Company/Organisation Austria Allianz Elementar Versicherungs-AG Company/Organisation Austria Alphaaffairs Kommunikationsberatung Company/Organisation Austria Alpine Bau Company/Organisation Austria Alstom Power Austria AG Company/Organisation Austria AMA - Agrarmarkt Austria Marketing Company/Organisation Austria Amnesty International Company/Organisation Austria AMS Arbeitsmarktservice – BundesgeschäftsstelleCompany/Organisation Austria AMS Burgenland Company/Organisation Austria AMS Kärnten Company/Organisation Austria AMS Niederösterreich Company/Organisation Austria AMS Oberösterreich Company/Organisation Austria AMS Salzburg Company/Organisation -

L'étude TNS-Ilres Plurimédia Luxembourg 2012/2013

Communiqué de presse Etude TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA LUXEMBOURG 2012/2013 Les résultats de la huitième édition de l’étude « TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA » réalisée par TNS ILRES et TNS MEDIA sont désormais disponibles. Cette étude qui informe sur l’audience des médias presse, radio, télévision, cinéma, dépliants publicitaires et Internet a été commanditée par les trois grands groupes de médias du pays: Editpress SA ; IP Luxembourg/CLT-UFA et Saint-Paul Luxembourg SA. L’étude a également été soutenue par le Gouvernement luxembourgeois. L’étude TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA a été réalisée par téléphone auprès d’un échantillon aléatoire de 3.044 personnes, représentatif de la population résidant au Grand-duché de Luxembourg, âgée de 12 ans et plus. Alors que la mesure d’audience des titres de presse se base sur l’univers des personnes âgées de 15 ans et plus, les résultats d’audience des autres médias se réfèrent supplémentairement sur l’univers 12+. Le terrain d’enquête s’est déroulé de septembre 2012 à mai 2013. Ci-après, vous trouverez quelques chiffres clés, concernant le lectorat moyen par période de parution, c’est-à-dire le lectorat par jour moyen pour les quotidiens, le lectorat par semaine moyenne pour les hebdomadaires, et ainsi de suite. Pour les médias audiovisuels les chiffres indiquent généralement l’audience par jour moyen, sauf pour le cinéma et les chaînes de télévision à diffusion spécifique où la période de référence est d’une semaine. Les résultats de l’étude obtenus auprès de l’échantillon aléatoire d’individus sont extrapolés à l’ensemble de la population de résidents au Luxembourg. -

Les Bibliothèques Du LCE

Les bibliothèques du LCE 1. Bibliothèque de travail Bâtiment « C », à côté du « Foyer » Lundi à vendredi : 08:00-15:30 hrs Bibliothèque de présence Les documents doivent être consultés sur place. Une photocopieuse (réservée aux copies de documents de la bibliothèque) est à la disposition des lecteurs. Fonds : Ouvrages de référence Dictionnaires Livres sur les matières enseignées … La bibliothèque est organisée selon la Classification décimale de Dewey. Périodiques : Quotidiens : Mensuels : Luxemburger Wort Read on Tageblatt Revue de la presse Journal Revista de la prensa Le Quotidien Dein Spiegel Zeitung vum Lëtzebuerger Vollek Geolino Mon quotidien G - Geschichte GeoAdo Hebdomadaires : Science et vie junior Der Spiegel Okapi Die Zeit Phosphore Time L’Histoire Le Nouvel Observateur Adesso Courrier international Ecos D'Lëtzebuerger Land Écoute Le Jeudi Spotlight Woxx I love English World Den Neie Feierkrop … Contacto Les périodiques marqués en vert sont empruntables pour la durée d’une semaine. Les autres périodiques doivent être consultés sur place. Ordinateurs : Usage strictement réservé à la recherche documentaire dans le cadre scolaire. 2. Bibliothèque des élèves Bâtiment « R » (Rotonde), 2e étage Lundi, mercredi, vendredi : 11:45 – 13:30 hrs Bibliothèque de prêt Durée du prêt : 6 semaines, pour 10 documents au maximum. L’emprunt se fait au moyen de la carte 'myCard'. Fonds : littérature jeunesse o romans réalistes, historiques, policiers, d’aventure, fantasy, … littérature générale livres simplifiés en français, anglais, espagnol, italien biographies, bandes dessinées, Luxemburgensia, … périodiques o J’aime lire Max o Je bouquine o Geolino extra 3. Informations générales Règles de conduite : Le respect du silence est indispensable afin de garantir une atmosphère propice à la lecture et au travail personnel. -

Des Cartes De Presse Remises Lire En Page 20 LUXEMBOURG Trente-Deux Journalistes Ont Reçu, Hier, Leur Carte De Presse Coup De Vieux À La Maison De La Presse

05.02.12 17:19:00 [Page partielle '13_LeQuotidien_0302' - EditPress | Editpress | Le Quotidien | Le Quotidien | LE PAYS] de Dillet Johann (PC 'FJS-01815') à Adobe PDF (Color feuille) (85% zoom) VENDREDI 3 FÉVRIER 2012 I www.lequotidien.lu STEINSEL DIX-SEPT ANS SANS AUTORISATION Lire en page 15 Le Premier ministre au lycée Le Premier ministre et prési- dent de l'Eurogroupe, Jean- Claude Juncker, était l'hôte d'une journée «Interlycées». Cette manifestation a réuni plus d'un millier de jeunes. Une belle tribune pour parler de l'Europe et de la Zone euro. Lire en page 16 Toute l'Europe grelotte Photo : martine may AHN À la faveur des températures polaires qui sévissent dans le pays, les grappes de raisin gelées nécessaires à l'élaboration du vin de glace ont été récoltées. La vague de froid qui touche Lire en page 17 actuellement le continent du- rera au moins deux semaines. Les morts se comptent déjà par dizaines en Europe de l'Est. Des cartes de presse remises Lire en page 20 LUXEMBOURG Trente-deux journalistes ont reçu, hier, leur carte de presse Coup de vieux à la Maison de la presse. en Lorraine e président du Conseil de L presse, Joseph Lorent, a ac- cueilli, hier, à la Maison de la presse, trente-deux journalistes pour une remise de cartes profes- sionnelles. Les journalistes ayant eu leur carte définitive sont : Andy Brücker (RTL NewMedia), Paulo Jorge Dos Santos Rodrigues Lobo (Luxedit), Dan Elvinger (Tageblatt), Raphaël Henry (ITnation), Pierre Hobscheit (freelance/Eldoradio), Frank Jaeger (RTL 93,3 & 97,0), Christiane Kleer (Le Quotidien), Oli- vier Landini (Le Quotidien), Pia Op- pel (freelance/ Woxx & radio 100,7), Sammy Pissinger (Nord- liicht TV), Dominique Seytre (free- lance/Le Jeudi) et Sébastien Vecrin Les statistiques sont sans ap- (Luxuriant). -

Communiqué De Presse

Communiqué de presse Etude TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA LUXEMBOURG 2010/2011 Les résultats de la sixième édition de l’étude « TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA » réalisée par TNS ILRES et TNS MEDIA sont désormais disponibles. Cette étude qui informe sur l’audience des médias presse, radio, télévision, cinéma, dépliants publicitaires et Internet a été commanditée par les trois grands groupes de médias du pays: Editpress SA ; IP Luxembourg/CLT-UFA et Saint-Paul Luxembourg SA. L’étude a également été soutenue par le Gouvernement luxembourgeois. L’étude TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA a été réalisée par téléphone auprès d’un échantillon aléatoire de 3.037 personnes, représentatif de la population résidant au Grand-duché de Luxembourg, âgée de 12 ans et plus. Alors que la mesure d’audience des titres de presse écrite se base sur l’univers des personnes âgées de 15 ans et plus, les résultats d’audience des autres médias se réfèrent supplémentairement sur l’univers 12+. Le terrain d’enquête s’est déroulé de septembre 2010 à mai 2011. Ci-après, vous trouverez quelques chiffres clés, concernant le lectorat moyen par période de parution, c’est-à-dire le lectorat par jour moyen pour les quotidiens, le lectorat par semaine moyenne pour les hebdomadaires, et ainsi de suite. Pour les médias audiovisuels les chiffres indiquent généralement l’audience par jour moyen, sauf pour le cinéma et les chaînes de télévision à diffusion spécifique où la période de référence est d’une semaine. Les résultats de l’étude obtenus auprès de l’échantillon aléatoire d’individus sont extrapolés à l’ensemble de la population de résidents au Luxembourg. -

It's Not All About RTL…

Fernand Weides Chairman of ALIA’s Consultative Assembly It’s not all about RTL… but mostly The Luxembourg Media Landscape 47th EPRA Conference – Mr. Fernand Weides - ALIA 28 May 2018 2 Some media milestones 1839: Luxembourg gains its independence 1931: Compagnie luxembourgeoise de radiodiffusion (CLR) is founded; it is later renamed CLT and CLT-Ufa Its radio and TV programmes are internationally marketed under the brand RTL 1988: SES launches its first Astra satellite Today more than 50 satellites reach 99% of the world population 47th EPRA Conference 28 May 2018 3 TV programmes RTL Hei elei, kuck elei (1969, weekly), morphed into RTL Télé Lëtzebuerg (1991, daily, audience: 104,700) 2ten RTL Télé Lëtzebuerg (2004) Uelzechtkanal (1996 weekly) Nordliicht TV (1997, weekly) AparTV (2017) Chamber TV (2001, weekly magazine plus live broadcast of public debates) 47th EPRA Conference – Mr. Fernand Weides - ALIA 28 May 2018 4 Radio programmes RTL Radio Lëtzebuerg (daily, 1959, audience : 183,200) radio 100,7 (public service, 1993, audience: 30,000) 4 commercial radios with regional coverage: Antenne Luxemburg (2017, audience: n.a.) Ara (1992, audience: 5,800) Eldoradio (1992, audience: 110.600, co-owned by CLT-Ufa & Editpress) L’essentiel-radio (2016, audience: 73,600, co-owned by CLT-Ufa & Editpress) 47th EPRA Conference – Mr. Fernand Weides - ALIA 28 May 2018 5 Daily newspapers Luxemburger Wort (1848, DE, FR, readership : 152,000) Tageblatt (1913, DE, FR, readership: 39,700) Le Quotidien (2001, FR only, readership: 25,100) Lëtzebuerger Journal (1948, DE, FR, readership: 5,700, owner: foundation close to Liberal Party) Zeitung vum Lëtzebuerger Vollék (1946, DE, FR, readership: 2,100, owner: Communist Party) L’essentiel (2007, FR only, free, readership: 200,000) 47th EPRA Conference – Mr.