Working Paper 3 – Julia De Bres: Multilingualism in Advertising and a Shifting Balance of Languages In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

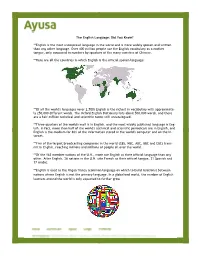

The English Language: Did You Know?

The English Language: Did You Know? **English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language. Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese. **Here are all the countries in which English is the official spoken language: **Of all the world's languages (over 2,700) English is the richest in vocabulary with approximate- ly 250,000 different words. The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 500,000 words, and there are a half-million technical and scientific terms still uncatalogued. **Three-quarters of the world's mail is in English, and the most widely published language is Eng- lish. In fact, more than half of the world's technical and scientific periodicals are in English, and English is the medium for 80% of the information stored in the world's computer and on the In- ternet. **Five of the largest broadcasting companies in the world (CBS, NBC, ABC, BBC and CBC) trans- mit in English, reaching millions and millions of people all over the world. **Of the 163 member nations of the U.N., more use English as their official language than any other. After English, 26 nations in the U.N. cite French as their official tongue, 21 Spanish and 17 Arabic. **English is used as the lingua franca (common language on which to build relations) between nations where English is not the primary language. In a globalized world, the number of English learners around the world is only expected to further grow. -

Bibliographie Courante De La Littérature Luxembourgeoise 2010

GRAND-DUCHÉ DE LUXEMBOURG MINISTÈRE DE LA CULTURE Daphné BOEHLES Bibliographie courante de la littérature luxembourgeoise BIBLIOGRAPHIE LITTÉRAIRE 2010 2010 (23e année) et compléments des années précédentes 2011 CENTRE NATIONAL DE LITTÉRATURE CENTRE NATIONAL DE LITTÉRATURE BIBLIOGRAPHIE LITTÉRAIRE 2010 Bibliographie courante de la littérature luxembourgeoise 2010 1 Impressum: Editeur: Centre national de littérature 2, rue E. Servais L-7565 Mersch 2011 Tirage: 600 exemplaires Imprimerie: Hengen ISSN 1016-328X 2 MINISTÈRE DE LA CULTURE Daphné BOEHLES Bibliographie courante de la littérature luxembourgeoise 2010 (23e année) et compléments des années précédentes CENTRE NATIONAL DE LITTÉRATURE MERSCH 2011 3 Sommaire Avant-propos p. 7 Photographies et abréviations p. 8 1 Linguistique et politique linguistique p. 9 2 Anthologies, bibliographies et ouvrages de référence p. 26 3 Histoire et critique p. 32 3-1 Essais et articles généraux p. 32 3-2 Auteurs luxembourgeois p. 45 3-3 Auteurs étrangers p. 59 4 Littérature d’expression luxembourgeoise p. 140 4-1 Livres p. 140 4-2 Contributions p. 143 4-3 Critiques p. 152 5 Littérature d’expression française p. 160 5-1 Livres p. 160 5-2 Contributions p. 169 5-3 Critiques p. 183 6 Littérature d’expression allemande p. 192 6-1 Livres p. 192 6-2 Contributions p. 203 6-3 Critiques p. 226 7 Littérature d’expression diverse p. 242 7-1 Livres p. 242 7-2 Contributions p. 253 7-3 Critiques p. 260 8 Traductions p. 268 8-1 Traductions par des auteurs luxembourgeois p. 268 8-2 Traductions d’auteurs luxembourgeois p. 268 9 Cabaret et théâtre p. -

Competing Language Ideologies About Societal Multilingualism Among Cross- Border Workers in Luxembourg

DOI 10.1515/ijsl-2013-0091 IJSL 2014; 227: 119 – 137 Julia de Bres Competing language ideologies about societal multilingualism among cross- border workers in Luxembourg Abstract: Cross-border workers, who live in the surrounding border regions of France, Belgium and Germany, now make up 44 percent of the workforce in Lux- embourg. This increasing presence of “foreigners” is prompting substantial change to Luxembourg’s traditionally triglossic language situation, where Lux- embourgish, French and German have coexisted in public use. In this situation, competing language ideologies emerge reflecting the interests of different groups. Through analysis of metalinguistic discourse in interviews with thirty cross- border workers in Luxembourg, this article examines how the language ideolo- gies of cross-border workers might contribute to competing perspectives on soci- etal multilingualism in Luxembourg. Keywords: language ideologies, cross-border workers, multilingualism, minority languages, Luxembourg Julia de Bres: The University of Luxembourg. E-mail: [email protected] 1 Introduction Luxembourg is a small country of 2,586 square kilometres and a population of 511,800 (STATEC 2011). Bordered by France, Belgium and Germany, it is also lo- cated on the border of the Romance and Germanic language families and histori- cally these larger neighbors have had an important influence on its unique lan- guage situation. With a national language (Luxembourgish) and three languages of administration (French, German and Luxembourgish), all of which are used on a daily basis, Luxembourg is one of the most multilingual countries in the world.1 This is ever more so with the increasing proportion of “foreigners”2 who now 1 Luxembourg’s language situation is not described in detail here. -

Multilingualism As a Resource for Learning – Insights from a Multidisciplinary Research Project

MOUTON EuJAL 2020; 8(2): 143–156 Editorial Adelheid Hu* and Ingrid de Saint-Georges Multilingualism as a resource for learning – insights from a multidisciplinary research project https://doi.org/10.1515/eujal-2020-0012 1 Globalisation, mobility and linguistic diversity Globalisation is a process full of complexities and inherent tensions. On the one hand, we are seeing increasing numbers of people from a variety of communities using a more diverse range of repertoires and entering into increasingly multi- lateral relationships. In this respect, globalisation is giving rise to more flexible and mixed views of identities, more hybrid language practices and new cultural scripts. But at the same time, perhaps as a response to these changes, we are witnessing the re-emergence of stronger nationalist and communitarian currents in many parts of the world. Under this new globalised regime, neighbourhoods, workplaces, schools and universities are changing in Europe and beyond. For example, the number of chil- dren, young people and adults learning to use and navigate new languages at different points in their lives has surged. In education, mobile learners have also contributed to the diversification of classrooms, raising new questions as to how best to support them in their educational trajectories, in particular when their linguistic repertoires do not correspond with the languages of schooling. Simulta- neously, issues related to fairness and equity have become more pressing in many spheres of social life. *Corresponding author: Prof. Adelheid Hu, University of Luxembourg, Faculty of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences, E-Mail: [email protected] Prof. Ingrid de Saint-Georges, University of Luxembourg, Faculty of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences, E-Mail: [email protected] 144 Adelheid Hu and Ingrid de Saint-Georges MOUTON 2 Luxembourg as a case study The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg represents an especially rich case study when investigating the linguistic ramifications of globalisation. -

Grand Duchy of Luxembourg History Culture Economy Education Population Population Languages Geography Political System System Political National Symbols National

Grand Duchy of Luxembourg of Duchy Grand Everything you need to know know needto you Everything Geography History about the Political system National symbols Economy Population Languages Education Culture Publisher Information and Press Service of the Luxembourg Government, Publishing Department Translator Marianne Chalmers Layout Repères Communication Printing Imprimerie Centrale ISBN 978-2-87999-232-7 September 2012 All statistics in this brochure are provided by Statec. Table of contents of Table 4 6 8 12 14 16 18 20 24 26 History Culture Economy Education Population Languages Geography At a glance a glance At Political system system Political National symbols National Everything you need to know about the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg of Duchy about the Grand know need to you Everything Official designation Territory Grand Duchy of Luxembourg Administrative division Capital • 3 districts (Luxembourg, Diekirch, Luxembourg Grevenmacher) • 12 cantons (Capellen, Clervaux, Diekirch, National day Echternach, Esch-sur-Alzette, Grevenmacher, 23 June Luxembourg, Mersch, Redange-sur-Attert, Remich, Vianden, Wiltz) Currency • 106 municipalities Euro • 4 electoral constituencies (South, East, Centre, North) Geography Judicial division At a glance At Geographical coordinates • 2 judicial districts (Luxembourg, Diekirch) comprising 3 magistrates’ courts Latitude 49° 37’ North and longitude 6° 08’ East (Luxembourg, Esch-sur-Alzette, Diekirch) Area 2,586 km2, of which 85.5% is farmland or forest Population (2011) Total population Neighbouring countries 524,900 inhabitants, including 229,900 foreign Belgium, Germany, France residents representing 43.8% of the total population (January 2012) Climate Luxembourg enjoys a temperate climate. Annual Most densely populated towns average temperatures range from -2.6° C (average Luxembourg (99,900 inhabitants) minimum value) to 21.6° C (average maximum Esch-sur-Alzette (30,900 inhabitants) value) (1981-2010). -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jana Krejčířová Australian English Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph.D. for her patience and valuable advice. I would also like to thank my partner Martin Burian and my family for their support and understanding. Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1. AUSTRALIA AND ITS HISTORY ................................................................. 10 1.1. Australia before the arrival of the British .................................................... 11 1.1.1. Aboriginal people .............................................................................. 11 1.1.2. First explorers .................................................................................... 14 1.2. Arrival of the British .................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Convicts ............................................................................................. 15 1.3. Australia in the -

Partitive Article

Book Disentangling bare nouns and nominals introduced by a partitive article IHSANE, Tabea (Ed.) Abstract The volume Disentangling Bare Nouns and Nominals Introduced by a Partitive Article, edited by Tabea Ihsane, focuses on different aspects of the distribution, semantics, and internal structure of nominal constituents with a “partitive article” in its indefinite interpretation and of potentially corresponding bare nouns. It further deals with diachronic issues, such as grammaticalization and evolution in the use of “partitive articles”. The outcome is a snapshot of current research into “partitive articles” and the way they relate to bare nouns, in a cross-linguistic perspective and on new data: the research covers noteworthy data (fieldwork data and corpora) from Standard languages - like French and Italian, but also German - to dialectal and regional varieties, including endangered ones like Francoprovençal. Reference IHSANE, Tabea (Ed.). Disentangling bare nouns and nominals introduced by a partitive article. Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020 DOI : 10.1163/9789004437500 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:145202 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Disentangling Bare Nouns and Nominals Introduced by a Partitive Article - 978-90-04-43750-0 Downloaded from PubFactory at 10/29/2020 05:18:23PM via Bibliotheque de Geneve, Bibliotheque de Geneve, University of Geneva and Universite de Geneve Syntax & Semantics Series Editor Keir Moulton (University of Toronto, Canada) Editorial Board Judith Aissen (University of California, Santa Cruz) – Peter Culicover (The Ohio State University) – Elisabet Engdahl (University of Gothenburg) – Janet Fodor (City University of New York) – Erhard Hinrichs (University of Tubingen) – Paul M. -

German and English Noun Phrases

RICE UNIVERSITY German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach Ward Keith Barrows A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF 3 1272 00675 0689 Master of Arts Thesis Directors signature: / Houston, Texas April, 1971 Abstract: German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach, by Ward Keith Barrows The paper presents a contrastive approach to German and English based on the theory of transformational grammar. In the first chapter, contrastive analysis is discussed in the context of foreign language teaching. It is indicated that contrastive analysis in pedagogy is directed toward the identification of sources of interference for students of foreign languages. It is also pointed out that some differences between two languages will prove more troublesome to the student than others. The second chapter presents transformational grammar as a theory of language. Basic assumptions and concepts are discussed, among them the central dichotomy of competence vs performance. Chapter three then present the structure of a grammar written in accordance with these assumptions and concepts. The universal base hypothesis is presented and adopted. An innovation is made in the componential structire of a transformational grammar: a lexical component is created, whereas the lexicon has previously been considered as part of the base. Chapter four presents an illustration of how transformational grammars may be used contrastively. After a base is presented for English and German, lexical components and some transformational rules are contrasted. The final chapter returns to contrastive analysis, but discusses it this time from the point of view of linguistic typology in general. -

New Zealand English

New Zealand English Štajner, Renata Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2011 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:005306 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Njemačkog jezika i književnosti Renata Štajner New Zealand English Završni rad Prof. dr. sc. Mario Brdar Osijek, 2011 0 Summary ....................................................................................................................................2 Introduction................................................................................................................................4 1. History and Origin of New Zealand English…………………………………………..5 2. New Zealand English vs. British and American English ………………………….….6 3. New Zealand English vs. Australian English………………………………………….8 4. Distinctive Pronunciation………………………………………………………………9 5. Morphology and Grammar……………………………………………………………11 6. Maori influence……………………………………………………………………….12 6.1.The Maori language……………………………………………………………...12 6.2.Maori Influence on the New Zealand English………………………….………..13 6.3.The -

English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate

ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 First published in 1993 by Rhodes University Grahamstown South Africa ©PROF LS WRIGHT -1993 Laurence Wright English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate ISBN: 0-620-03155-7 No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Mr Vice Chancellor, my former teachers, colleagues, ladies and gentlemen: It is a special privilege to be asked to give an inaugural lecture before the University in which my undergraduate days were spent and which holds, as a result, a special place in my affections. At his own "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" in 1866, Thomas Carlyle observed that "the true University of our days is a Collection of Books".1 This definition - beloved of university library committees worldwide - retains a certain validity even in these days of microfiche and e-mail, but it has never been remotely adequate. John Henry Newman supplied the counterpoise: . no book can convey the special spirit and delicate peculiarities of its subject with that rapidity and certainty which attend on the sympathy of mind with mind, through the eyes, the look, the accent and the manner. -

Rédacteurs En Chef De La Presse Luxembourgeoise 93

Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Agenda Plurionet Frank THINNES boulevard Royal 51 L-2449 Luxembourg +352 46 49 46-1 [email protected] www.plurio.net agendalux.lu BP 1001 L-1010 Luxembourg +352 42 82 82-32 [email protected] www.agendalux.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Hebdomadaires d'Lëtzeburger Land M. Romain HILGERT BP 2083 L-1020 Luxembourg +352 48 57 57-1 [email protected] www.land.lu Woxx M. Richard GRAF avenue de la Liberté 51 L-1931 Luxembourg +352 29 79 99-0 [email protected] www.woxx.lu Contacto M. José Luis CORREIA rue Christophe Plantin 2 L-2988 Luxembourg +352 4993-315 [email protected] www.contacto.lu Télécran M. Claude FRANCOIS BP 1008 L-1010 Luxembourg +352 4993-500 [email protected] www.telecran.lu Revue M. Laurent GRAAFF rue Dicks 2 L-1417 Luxembourg +352 49 81 81-1 [email protected] www.revue.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Correio Mme Alexandra SERRANO ARAUJO rue Emile Mark 51 L-4620 DIfferdange +352 444433-1 [email protected] www.correio.lu Le Jeudi M. Jacques HILLION rue du Canal 44 L-4050 Esch-sur-Alzette +352 22 05 50 [email protected] www.le-jeudi.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Quotidiens Zeitung vum Lëtzebuerger Vollek M. Ali RUCKERT - MEISER rue Zénon Bernard 3 L-4030 Esch-sur-Alzette +352 446066-1 [email protected] www.zlv.lu Le Quotidien M. -

New Zealand Ways of Speaking English Edited by Allan Bell and Janet Holmes

UCLA Issues in Applied Linguistics Title New Zealand Ways of Speaking English edited by Allan Bell and Janet Holmes. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters, 1990. 305 pp. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/77n0788f Journal Issues in Applied Linguistics, 2(1) ISSN 1050-4273 Author Locker, Rachel Publication Date 1991-06-30 DOI 10.5070/L421005133 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California REVIEWS New Zealand Ways of Speaking English edited by Allan Bell and Janet Holmes. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters, 1990. 305 pp. Reviewed by Rachel Locker University of California, Los Angeles Coming to America has resulted in an interesting encounter with my linguistic identity, my New Zealand accent regularly provoking at least two distinct reactions: either "Please say something, I love the way you talk!" (which causes me some amusement but mainly disbelief), or "Your English is very good- what's your native language?" It is difficult to review a book like New Zealand Ways of Speaking English without relating such experiences, because as a nation New Zealanders at home and abroad have long suffered from a lurking sense of inferiority about the way they speak English, especially compared with those in the colonial "homeland," i.e., England. That dialectal differences create attitudes about what is better and worse is no news to scholars of language use, but this collection of studies on New Zealand English (NZE) not only reveals some interesting peculiarities of that particular dialect and its speakers from "down- under"; it also makes accessible the significant contributions of New Zealand linguists to broader theoretical concerns in sociolinguistics and applied linguistics.