Chapter 8 Luxembourg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spaces and Identities in Border Regions

Christian Wille, Rachel Reckinger, Sonja Kmec, Markus Hesse (eds.) Spaces and Identities in Border Regions Culture and Social Practice Christian Wille, Rachel Reckinger, Sonja Kmec, Markus Hesse (eds.) Spaces and Identities in Border Regions Politics – Media – Subjects Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Natio- nalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de © 2015 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or uti- lized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover layout: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Cover illustration: misterQM / photocase.de English translation: Matthias Müller, müller translations (in collaboration with Jigme Balasidis) Typeset by Mark-Sebastian Schneider, Bielefeld Printed in Germany Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-2650-6 PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-2650-0 Content 1. Exploring Constructions of Space and Identity in Border Regions (Christian Wille and Rachel Reckinger) | 9 2. Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to Borders, Spaces and Identities | 15 2.1 Establishing, Crossing and Expanding Borders (Martin Doll and Johanna M. Gelberg) | 15 2.2 Spaces: Approaches and Perspectives of Investigation (Christian Wille and Markus Hesse) | 25 2.3 Processes of (Self)Identification(Sonja Kmec and Rachel Reckinger) | 36 2.4 Methodology and Situative Interdisciplinarity (Christian Wille) | 44 2.5 References | 63 3. Space and Identity Constructions Through Institutional Practices | 73 3.1 Policies and Normalizations | 73 3.2 On the Construction of Spaces of Im-/Morality. -

Communiqué De Presse

Communiqué de presse Etude TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA LUXEMBOURG 2014/2015 Les résultats de la dixième édition de l’étude « TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA » réalisée par TNS ILRES et TNS MEDIA sont désormais disponibles. Cette étude qui informe sur l’audience des médias presse, radio, télévision, cinéma, dépliants publicitaires et Internet a été commanditée par les trois grands groupes de médias du pays: Editpress SA ; IP Luxembourg/CLT-UFA et Saint-Paul Luxembourg SA. L’étude a également été soutenue par le Gouvernement luxembourgeois. Depuis sa 1ère édition conduite en 2005-2006, l’étude Plurimédia était exclusivement réalisée moyennant un sondage téléphonique assisté par ordinateur (CATI). Considérant les évolutions de la société luxembourgeoise en matière d’usage des télécommunications et d’Internet, cette dixième édition de l’enquête est basée pour partie sur des enquêtes téléphoniques, pour une autre par Internet. L’objectif étant d’élargir la base de sondage et ainsi assurer une plus grande représentativité des résultats. L’étude TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA a donc été réalisée auprès d’un échantillon aléatoire de 4.103 personnes (3.011 par téléphone, 1 092 par internet), représentatif de la population résidant au Grand-duché de Luxembourg, âgée de 12 ans et plus. Alors que la mesure d’audience des titres de presse se base sur l’univers des personnes âgées de 15 ans et plus, les résultats d’audience des autres médias se réfèrent supplémentairement sur l’univers 12+. Le terrain d’enquête s’est déroulé d’octobre 2014 à fin mai 2015. Ci-après, vous trouverez quelques chiffres clés, concernant le lectorat moyen par période de parution, c’est-à-dire le lectorat par jour moyen pour les quotidiens, le lectorat par semaine moyenne pour les hebdomadaires, et ainsi de suite. -

ARNY SCHMIT (Luxembourg, 1959)

ARNY SCHMIT (Luxembourg, 1959) Arny Schmit is a storyteller, a conjurer, a traveler of time and space. From the myth of Leda to the images of an exhibitionist blogger, from the house of a serial killer to the dark landscapes of a Caspar David Friedrich, he makes us wander through a universe that tends towards the sublime. Manipulating the mimetic properties of painting while referring to the virtual era in which we live, the Luxembourgish artist likes to surprise by playing on the false pretenses. In his paintings he creates bridges between reality, fantasy and nightmare. The medieval, baroque or romantic references reveal his profound respect for the masters of the past. Extracted from a different time era, decorative motifs populate his compositions like so many childhood memories, from the floral wallpaper to the dusty Oriental carpet, through the models of embroidery. Through fragmentation, juxtaposition and collage, Arny Schmit multiplies the reading tracks and digs the strata of the image. The beauty of his women contrasts with their loneliness and sadness, the enticing colors are soiled with spurts, the shapes are torn to reveal the underlying, the reverse side of the coin, the unknown. 1 EXHIBITION – DECEMBER 1st, 2018 to FEBRUARY 28th, 2019 ARNY SCHMIT – WILD 13 windows with a view on the wilderness. Recent works by Luxembourgish painter Arny Schmit depict his vision of a daunting and nurturing nature and its relationship with the female body. A body that Schmit likes to fragment by imprisoning it into frames of analysis, each frame a clue into a mysterious narrative, a suggestion, an impression. -

Annual Report 2019 Key Figures

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ENTERTAIN. INFORM. ENGAGE. KEY FIGURES SHARE PERFORMANCE 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2019 +31.15 % MDAX +16.41 % SXMP –5.82 % RTL GROUP INDEX = 100 –10.55 % RTL Group share price development PROSIEBENSAT1 for January to December 2019 based on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange (Xetra) against MDAX, Euro Stoxx 600 Media (SXMP) and ProSiebenSat1 Fremantle’s America’s Got Talent: The Champions is a prime-time hit on NBC. 2 RTL Group Annual Report 2019 Key figures REVENUE 2015 – 2019 (€ million) EBITA 2015 – 2019 (€ million) 19 6,651 19 1,139 18 6,505 18 1,171 17 6,373 17 1,248 16 6,237 16 1,205 15 6,029 15 1,167 PROFIT FOR THE YEAR 2015 – 2019 (€ million) EQUITY 2015 – 2019 (€ million) 19 864 19 3,825 18 785 18 3,553 17 837 17 3,432 16 816 16 3,552 15 863 15 3,409 MARKET CAPITALISATION* 2015 – 2019 (€ billion) TOTAL DIVIDEND / DIVIDEND YIELD PER SHARE 2015 – 2019 (€)(%) 19 6.8 19 NIL* – 18 7.2 18 4.00** 6.3 17 10.4 17 4.00*** 5.9 16 10.7 16 4.00**** 5.4 15 11.9 15 4.00***** 4.9 *As of 31 December * On 2 April 2020, RTL Group’s Board of Directors decided to withdraw its earlier proposal of a € 4.00 per share dividend in respect of the fiscal year 2019, due to the coronavirus outbreak. No dividend will now be proposed to the Annual Meeting of Shareholders on 30 June 2020. -

Television Advertising Insights

Lockdown Highlight Tous en cuisine, M6 (France) Foreword We are delighted to present you this 27th edition of trends and to the forecasts for the years to come. TV Key Facts. All this information and more can be found on our This edition collates insights and statistics from dedi cated TV Key Facts platform www.tvkeyfacts.com. experts throughout the global Total Video industry. Use the link below to start your journey into the In this unprecedented year, we have experienced media advertising landscape. more than ever how creative, unitive, and resilient Enjoy! / TV can be. We are particularly thankful to all participants and major industry players who agreed to share their vision of media and advertising’s future especially Editors-in-chief & Communications. during these chaotic times. Carine Jean-Jean Alongside this magazine, you get exclusive access to Coraline Sainte-Beuve our database that covers 26 countries worldwide. This country-by-country analysis comprises insights for both television and digital, which details both domestic and international channels on numerous platforms. Over the course of the magazine, we hope to inform you about the pandemic’s impact on the market, where the market is heading, media’s social and environmental responsibility and all the latest innovations. Allow us to be your guide to this year’s ACCESS OUR EXCLUSIVE DATABASE ON WWW.TVKEYFACTS.COM WITH YOUR PERSONAL ACTIVATION CODE 26 countries covered. Television & Digital insights: consumption, content, adspend. Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, Croatia, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Hungary, India, Italy, Ireland, Japan, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Russia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, UK and the US. -

European Citizen Information Project FINAL REPORT

Final report of the study on “the information of the citizen in the EU: obligations for the media and the Institutions concerning the citizen’s right to be fully and objectively informed” Prepared on behalf of the European Parliament by the European Institute for the Media Düsseldorf, 31 August 2004 Deirdre Kevin, Thorsten Ader, Oliver Carsten Fueg, Eleftheria Pertzinidou, Max Schoenthal Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Executive Summary 5 Part I Introduction 8 Part II: Country Reports Austria 15 Belgium 25 Cyprus 35 Czech Republic 42 Denmark 50 Estonia 58 Finland 65 France 72 Germany 81 Greece 90 Hungary 99 Ireland 106 Italy 113 Latvia 121 Lithuania 128 Luxembourg 134 Malta 141 Netherlands 146 Poland 154 Portugal 163 Slovak Republic 171 Slovenia 177 Spain 185 Sweden 194 United Kingdom 203 Part III Conclusions and Recommendations 211 Annexe 1: References and Sources of Information 253 Annexe 2: Questionnaire 263 2 Acknowledgements The authors wish to express their gratitude to the following people for their assistance in preparing this report, and its translation, and also those national media experts who commented on the country reports or helped to provide data, and to the people who responded to our questionnaire on media pluralism and national systems: Jean-Louis Antoine-Grégoire (EP) Gérard Laprat (EP) Kevin Aquilina (MT) Evelyne Lentzen (BE) Péter Bajomi-Lázár (HU) Emmanuelle Machet (FR) Maria Teresa Balostro (EP) Bernd Malzanini (DE) Andrea Beckers (DE) Roberto Mastroianni (IT) Marcel Betzel (NL) Marie McGonagle (IE) Yvonne Blanz (DE) Andris Mellakauls (LV) Johanna Boogerd-Quaak (NL) René Michalski (DE) Martin Brinnen (SE) Dunja Mijatovic (BA) Maja Cappello (IT) António Moreira Teixeira (PT) Izabella Chruslinska (PL) Erik Nordahl Svendsen (DK) Nuno Conde (PT) Vibeke G. -

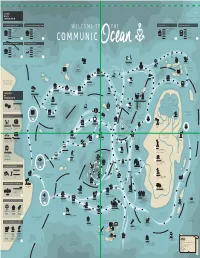

51% 49% 71% 16% 16%

THE WAY WE USE MERKUR - INF OGRAPHIC - C OMMUNICOCEAN - MA Y/JUNE 2015 COMMUNICATION USE OF DAILY NEWSPAPERS (TOP 5) USE OF WEEKLY & BI MONTHLY MAGAZINES (TOP 5) USE OF TV-STATIONS USE OF WEB-SITES (TOP 5) 39,0% LUXEMBURGER WORT 32,8% AUTOTOURING 25,2% RTL TELE LETZEBUERG 25,7% RTL.LU 29,5% L´ESSENTIEL 14,3% AUTO REVUE 3,8% NORDLIICHT TV 16,9% WORT.LU 9,3% TAGEBLATT 13,9% AUTOMOTO 2,1% CHAMBER TV 11,3% L´ESSENTIEL.LU 5,7% LE QUOTIDIEN 11,3% PAPERJAM ... ... 9,2% PUBLIC.LU 2,1% LETZEBUERGER JOURNAL 9,6% CITY MAG ... ... 4,7% TAGEBLATT.LU USE OF MONTHLY MAGAZINES (TOP 5) USE OF RADIO-SATIONS (TOP 5) 23,0% TÉLÉCRAN 36,8% RTL RADIO LETZEBUERG 17,0% LUX-POST WEEK-END 19,6% ELDORADIO 15,7% REVUE 8,5% RTL (GERMAN LANGUAGE) 12,1% CONTACTO 5,4% RADIO LATINA 7,7% LUXBAZAR 4,5% RADIO 100,7 NEW IDEA PRINT MEDIA STORY TELLING 2010s - PRINT NATIVE IN DANGER ADVERTISING MESSENGERS SEA OF PRINT CREATIVITY TRENDY COAST TEXTUAL C ONTENT FRESH IDEAS ISLANDS BUSINESS PLAN FREE NEW SPAPER INFOGRAPHICS 2007 - 1st ISSUE OF L’ESSENTIEL BIG BUDGET FEE / DUTY MAGAZINE MESSENGERS DATA 1932 - 1st MA GAZINE VISUALIZATION CONTINENT AUTOTOURING BY CONSEIL DE AUTOMOBILE CLUB PRESSE M PICTURES A NEWSPAPER I 1848 - 1st ISSUE OF N PRINTING NEWSPAPER RACING PIGE ON LUXEMBURGER WORT S THE HISTORY 1900s - 1st ME CHANIC 1913 - 1st ISSUE 776 B.C. - WINNER LIST COMPUTER PRINTER OF TAGEBLATT LOW BUDGET T OF OF OLYMPIC GAMES SENT R COMMUNICATION BY DOVES E AGE A LANGUAGE B ARRIER REEF NATIO- M NALITY 70,5% LUXEMBOURGISH N E W S P A P E R 55,7% FRENCH GENDER PROF- A REVOLUTION BEGAN 1650 - 1st DAILY 30,6% GERMAN ESSION AS MANKIND STARTED NEWSPAPER 21,0% ENGLISH TO BIND MESSAGES 20,0% PORTUGUESE TO TIME & TO SPACE BIG BUDGET CONSEIL DE HOBBIES PUBLICITÉ INCOME EDU- CLIENTS FUN CATION COAST HOW DID THEY DO THIS ? PRINT R OUTE REPRODUCTION CLIENTS 1450 - GUTENBER G EMOTIONS BUDGET INVENTS PRINT LETTERS COAST CONFUSION TELEVISION TRIANGLE TIME BINDING DEFINITION 1970 - ST ART OF TV-SPOT VISUAL 30.000 B.C. -

Rédacteurs En Chef De La Presse Luxembourgeoise 93

Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Agenda Plurionet Frank THINNES boulevard Royal 51 L-2449 Luxembourg +352 46 49 46-1 [email protected] www.plurio.net agendalux.lu BP 1001 L-1010 Luxembourg +352 42 82 82-32 [email protected] www.agendalux.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Hebdomadaires d'Lëtzeburger Land M. Romain HILGERT BP 2083 L-1020 Luxembourg +352 48 57 57-1 [email protected] www.land.lu Woxx M. Richard GRAF avenue de la Liberté 51 L-1931 Luxembourg +352 29 79 99-0 [email protected] www.woxx.lu Contacto M. José Luis CORREIA rue Christophe Plantin 2 L-2988 Luxembourg +352 4993-315 [email protected] www.contacto.lu Télécran M. Claude FRANCOIS BP 1008 L-1010 Luxembourg +352 4993-500 [email protected] www.telecran.lu Revue M. Laurent GRAAFF rue Dicks 2 L-1417 Luxembourg +352 49 81 81-1 [email protected] www.revue.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Correio Mme Alexandra SERRANO ARAUJO rue Emile Mark 51 L-4620 DIfferdange +352 444433-1 [email protected] www.correio.lu Le Jeudi M. Jacques HILLION rue du Canal 44 L-4050 Esch-sur-Alzette +352 22 05 50 [email protected] www.le-jeudi.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Quotidiens Zeitung vum Lëtzebuerger Vollek M. Ali RUCKERT - MEISER rue Zénon Bernard 3 L-4030 Esch-sur-Alzette +352 446066-1 [email protected] www.zlv.lu Le Quotidien M. -

Frequenzliste Digital-TV Per 21.07.2021

Frequenzliste Digital-TV per 21.07.2021 LCN LCN Sender Name Red- Norm Sender- Free / Frequenz Service- TS-ID Modula- N-ID: N-ID: Button Typ2 Pay [kHz] ID (SID) tion 1 360 1 1 SRF 1 HD HbbTV HDTV MPEG-4 338000 10091 826 QAM256 2 2 SRF zwei HD HbbTV HDTV MPEG-4 338000 10092 826 QAM256 3 3 SRF info HD HbbTV HDTV MPEG-4 266000 20020 818 QAM256 4 4 Thurcom HD HbbTV HDTV MPEG-4 210000 10100 820 QAM256 5 5 3+ HD HDTV MPEG-4 314000 10110 830 QAM256 6 6 4+ HD HDTV MPEG-4 314000 10111 830 QAM256 7 7 Das Erste HD HbbTV HDTV MPEG-4 210000 10210 820 QAM256 8 8 ZDF HD HbbTV HDTV MPEG-4 218000 10220 821 QAM256 9 9 ORF 1 HD HbbTV HDTV MPEG-4 242000 10250 824 QAM256 10 10 ORF 2 HD HbbTV HDTV MPEG-4 242000 10251 824 QAM256 11 911 RTL HD CH HbbTV HDTV MPEG-4 Conax 354000 20076 831 QAM256 12 912 RTL ZWEI HD CH HbbTV HDTV MPEG-4 Conax 354000 20081 831 QAM256 13 913 SAT.1 HD CH HDTV MPEG-4 Conax 250000 20114 833 QAM256 14 14 ProSieben MAXX CH SD MPEG-2 770000 20090 812 QAM256 15 915 ProSieben HD CH HDTV MPEG-4 Conax 250000 20116 833 QAM256 16 916 VOX HD CH HbbTV HDTV MPEG-4 Conax 354000 20111 831 QAM256 17 917 KABEL EINS HD CH HDTV MPEG-4 Conax 250000 20119 833 QAM256 18 18 Disney Channel SD MPEG-2 266000 20130 818 QAM256 19 19 TELE 5 SD MPEG-2 770000 20125 812 QAM256 20 920 SIXX HD CH HDTV MPEG-4 Conax 250000 20118 833 QAM256 21 21 DMAX HD HDTV MPEG-4 754000 20226 810 QAM256 22 22 TLC HD HDTV MPEG-4 802000 20150 807 QAM256 23 23 ServusTV HD HbbTV HDTV MPEG-4 274000 10260 819 QAM256 24 24 TV24 HD HDTV MPEG-4 754000 20432 810 QAM256 25 25 TVO HD HDTV MPEG-4 -

6. Images and Identities

6. Images and Identities Wilhelm Amann, Viviane Bourg, Paul Dell, Fabienne Lentz, Paul Di Felice, Sebastian Reddeker 6.1 IMAGES OF NATIONS AS ‘INTERDISCOURSES’. PRELIMINARY THEORETICAL REFLECTIONS ON THE RELATION OF ‘IMAGES AND IDENTITIES’: THE CASE OF LUXEMBOURG The common theoretical framework for the analysis of different manifestations of ‘images and identities’ in the socio-cultural region of Luxembourg is provided by the so-called interdiscourse analysis (Gerhard/Link/Parr 2004: 293-295). It is regarded as an advancement and modification of the discourse analysis developed by Michel Foucault and, as an applied discourse theory, its main aim is to establish a relationship between practice and empiricism. While the discourses analysed by Foucault were, to a great extent, about formations of positive knowledge and institutionalised sciences (law, medicine, human sciences etc.), the interdiscourse analysis is interested in discourse complexes which are precisely not limited by specialisation, but that embrace a more comprehensive field and can therefore be described as ‘interdiscursive’ (Parr 2009). The significance of such interdiscourses arises from the general tension between the increasing differentiation of modern knowledge and the growing disorientation of modern subjects. In this sense, ‘Luxembourg’ can be described as a highly complex entity made up of special forms of organisation, e.g. law, the economy, politics or also the health service. Here, each of these sectors, as a rule, develops very specified styles of discourse restricted to the respective field, with the result that communication about problems and important topics even between these sectors is seriously impeded and, more importantly, that the everyday world and the everyday knowledge of the subjects is hardly ever reached or affected. -

National Distribution Lists of Media for the "Help" Campaign

LUXEMBOURG Nom du Mediaatt05072611563078719EA79657.xls Rédacteur en chef Ville Presse quotidienne Letzeburger Journal Claude Karger Luxembourg Letzeburger Journal Colette Mart Luxembourg La Voix du Luxembourg Laurent Moyse Luxembourg Le Quotidien Denis Berche Esch-sur-Alzette Luxemburger Wort Léon Zeches / Jean Louis scheffen Luxembourg Tageblatt Alvin Sold/Romain Durlier Esch-sur-Alzette Zeitung vum Letzebuerger Vollek Ali Ruckert Luxembourg Presse Hebdomadaire Contacto José Correia Luxembourg Correio José Dias Luxembourg d'Letzeburger Land Mario Hirsch Luxembourg Le Jeudi Jacques Hillion Esch-sur-Alzette Revue Stefan Kunzmann Luxembourg Revue Claude Wolf Luxembourg Télécran Roland Arens Luxembourg Télécran Martine Folscheid Luxembourg Télécran Britta Schlueter Luxembourg Woxx Robert Garcia Luxembourg Presse Mensuelle Agefi Luxembourg Olivier Minguet Capellen Femmes Magazine Maria Pietrangelli Luxembourg Le Monde Diplomatique Francis Wagner Esch-sur-Alzette Nico Mike Koedinger Luxembourg paperJam Jean Michel Gaudron Luxembourg paperJam Francis Gasparotto Luxembourg paperJam Ludivine Plessy Luxembourg paperJam Florence Reinson Luxembourg RADIO DNR Isabelle Decker Luxembourg DNR Radio Jean-Marc Sturm Luxembourg Eldoradio Isabel Galiano / ivano Andressini Luxembourg Radio ARA Radio Latina Gomes Avelinos Luxembourg Radio socio-culturelle 100,7 Fernand Weides Luxembourg RTL Radio Letzebuerg Marc Linster Luxembourg Radio Latina Gomes Avelinos Luxembourg Radio Latina Serge Ferreira Luxembourg TELEVISION att05072611563078719EA79657.xls TTV Daniel -

The Role of Commercial Radio Stations in the Media Vacuum of Mai 68 in Paris

volume 7 issue 12/2018 THE ROLE OF COMMERCIAL RADIO STATIONS IN THE MEDIA VACUUM OF MAI 68 IN PARIS Richard Legay C²DH Luxembourg Centre for Contemporary and Digital History Université du Luxembourg Maison des Sciences Humaines 11, Porte des Sciences L - 4366 Esch-Belval Luxembourg [email protected] Abstract: Commercial radio stations RTL and Europe n°1 played an important role during the events of May 1968 in Paris by maintaining the news coverage of the protests, the riots and the strikes. By analyzing the entanglements of the various audiovisual media and surviving audio material, this article defends the idea that a vacuum created by the crisis that affected the French public broadcasting agency is one of the main reasons that brought the commercial radio stations to the centre of the events. Keywords: radio, France, entanglements, ORTF, RTL, Europe 1. The media played a crucial role in the understanding of the events of Mai 68 in Paris, as the video footage and numerous photographs available to historians revealed. These great testimonies were tremendous sources for researchers. In France however, it was the commercial radio stations that were at the centre of attention during the events,1 as they were the main source of information through their live news coverage of Mai 68. The radio stations RTL (Radio-Télévision-Luxembourg) and Europe n°1 were listened to by many throughout the entire month and were even nicknamed “radio barricades” by Prime Minister Georges Pompidou.2 Through this live coverage of events, the commercial radio stations informed listeners of what was happening and where; they retransmitted important speeches and gave a voice to crucial actors.