6. Images and Identities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spaces and Identities in Border Regions

Christian Wille, Rachel Reckinger, Sonja Kmec, Markus Hesse (eds.) Spaces and Identities in Border Regions Culture and Social Practice Christian Wille, Rachel Reckinger, Sonja Kmec, Markus Hesse (eds.) Spaces and Identities in Border Regions Politics – Media – Subjects Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Natio- nalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de © 2015 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or uti- lized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover layout: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Cover illustration: misterQM / photocase.de English translation: Matthias Müller, müller translations (in collaboration with Jigme Balasidis) Typeset by Mark-Sebastian Schneider, Bielefeld Printed in Germany Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-2650-6 PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-2650-0 Content 1. Exploring Constructions of Space and Identity in Border Regions (Christian Wille and Rachel Reckinger) | 9 2. Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to Borders, Spaces and Identities | 15 2.1 Establishing, Crossing and Expanding Borders (Martin Doll and Johanna M. Gelberg) | 15 2.2 Spaces: Approaches and Perspectives of Investigation (Christian Wille and Markus Hesse) | 25 2.3 Processes of (Self)Identification(Sonja Kmec and Rachel Reckinger) | 36 2.4 Methodology and Situative Interdisciplinarity (Christian Wille) | 44 2.5 References | 63 3. Space and Identity Constructions Through Institutional Practices | 73 3.1 Policies and Normalizations | 73 3.2 On the Construction of Spaces of Im-/Morality. -

Rapport D'activité 2018 Du Centre National De Littérature

Rapport d’activité 2018 Centre national de littérature 2019 www.culture.lu www.gouvernement.lu/mc Table des matières 1. Centre national de littérature ....................................................................................... 3 1.1 La littérature et la recherche comme élément constitutif de la société de la connaissance ................................................................................................................. 3 1.1.1 Expositions ................................................................................................................... 3 1.1.2 Publications ................................................................................................................. 4 1.1.3 Numérisation ............................................................................................................... 9 1.1.4 Bibliothèque et archives ............................................................................................ 10 1.1.5 Coopérations ............................................................................................................. 10 1.1.6 Journées du livre et des droits d’auteurs .................................................................. 11 1.1.7 Bourse Bicherfrënn .................................................................................................... 12 1.1.8 Dictionnaire des auteurs ........................................................................................... 12 1.2 La littérature accessible à tous ............................................................................12 -

A Day in Luxembourg, LUXEMBOURG

A Day in Luxembourg, LUXEMBOURG Why you should visit Luxembourg Luxembourg is the epitome of “the charming European city” we all grew up imagining. It’s amazingly cosmopolitan but not overwhelming, except for its extremely complex history. Its gorges traverse the city, making it a spectacular three-dimensional city, with lit-up fortifications along the walls of the gorges -- perfect for the historian and the romantic. And the food is a lovely mix of French, German, Italian and of course Luxembourgish. Three things you might be surprised to learn about Luxembourg and the people 1. Luxembourg is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site due to its old quarters and fortifications. 2. General George Patton is buried here 3. Villeroy & Boch ceramics started in Luxembourg Favorite Walks/areas of town Go to the visitors center in Place Guillaume to sign up for any of the many fantastic—and reasonably priced—group or individual walking, biking or driving (even in your own car) historic tours with an official guide. The tours can include visits to: • Historic city center • The Petrusse gorge next to the city center • The historic Grund, down below the city center • Clausen, near the Grund • Petrusse and Bock Casemates Other very good things to do/see • American Military Cemetery, Hamm: A beautiful cemetery with more than 5,000 soldiers, most of whom fell in the Battle of the Bulge of WWII in 1944-45. The cemetery also has an impressive chapel and is the burial place of General George Patton. www.abmc.gov/cemeteries/cemeteries/lx.php • German Military Cemetery, Sandweiler: A short drive from the Hamm cemetery, this cemetery has a much more somber feel to it, containing more than 10,000 German soldiers who perished in the Battle of the Bulge in 1944-45. -

ROMA and LUXEMBOURGERS There Are People Who Love And

ROMA AND LUXEMBOURGERS There are people who love and people who hate Europe. I happen to be a fan. The European Union ended wars, queuing up for the customs and it gave a voice to even the smallest member-states, like Luxemburg with 500.000 residents. Yet millions of other EU citizens have no say in the matter, no Commissioner of their own and no MEPs in Brussels, for the mere reason that they are an ethnic minority, like Roma and Sinti, Europe's largest minority. Why double standards? Is it because Luxembourgers are all white and Roma all dark? They are not. Thousand years ago, Roma left India and went to Russia, Persia, Turkey and Europe. Some intermarried with Jews and other non-Roma, or they lost their tan in Scandinavian countries. Even the Nazis noticed that racial purity is a difficult thing. They decided that 12.5 % of Roma or Jewish blood was enough to be deported. Gadje, non-Roma, also have mixed blood. New archeological findings reveal that only 10 up to 20 % of Europeans descend from the original tribes, the others have DNA from the Middle East or Asia. The major difference between Luxembourgers and Roma does not stem from ethnicity but from something that used to be very important in Europe: borders. Luxembourgers have them, Roma don't. The political relevance of the term "ethnic minority" is rather dubious. It means counting people in, not seldom to count them out. The reunification of Europe has deprived a whole nation from fundamental rights and this mainly happened because the 12 million Roma, present in larger numbers than Belgians, Swedes, Finns, Bulgarians, Czechs, Greeks, Danish, or Luxembourgers, did not live together in their own nation-state. -

Luxembourg Resistance to the German Occupation of the Second World War, 1940-1945

LUXEMBOURG RESISTANCE TO THE GERMAN OCCUPATION OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR, 1940-1945 by Maureen Hubbart A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Major Subject: History West Texas A&M University Canyon, TX December 2015 ABSTRACT The history of Luxembourg’s resistance against the German occupation of World War II has rarely been addressed in English-language scholarship. Perhaps because of the country’s small size, it is often overlooked in accounts of Western European History. However, Luxembourgers experienced the German occupation in a unique manner, in large part because the Germans considered Luxembourgers to be ethnically and culturally German. The Germans sought to completely Germanize and Nazify the Luxembourg population, giving Luxembourgers many opportunities to resist their oppressors. A study of French, German, and Luxembourgian sources about this topic reveals a people that resisted in active and passive, private and public ways. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Clark for her guidance in helping me write my thesis and for sharing my passion about the topic of underground resistance. My gratitude also goes to Dr. Brasington for all of his encouragement and his suggestions to improve my writing process. My thanks to the entire faculty in the History Department for their support and encouragement. This thesis is dedicated to my family: Pete and Linda Hubbart who played with and took care of my children for countless hours so that I could finish my degree; my husband who encouraged me and always had a joke ready to help me relax; and my parents and those members of my family living in Europe, whose history kindled my interest in the Luxembourgian resistance. -

Core Strengths, Sustainable Returns

Core strengths, sustainable returns Annual Report 2011 With revenues of $94 billion and crude steel production of 91.9 million tonnes, ArcelorMittal is the world’s leading steel and mining company, with a presence in more than 60 countries. Through our core values of sustainability, quality and leadership, we commit to operating in a responsible way with respect to the health, safety and well-being of our employees, contractors and the communities in which we operate. The theme for this year’s annual report is ‘core strengths, sustainable returns’. We believe consistency is crucial in a fast-changing world. And at the heart of this belief is a consistent strategy that focuses on our five core strengths. By continually focusing on these strengths throughout our operations, ArcelorMittal can deliver sustainable returns. Cover image Port-Cartier, Canada Global presence ArcelorMittal is the world’s leading steel and mining company. With a presence in more than 60 countries, we operate a balanced portfolio of cost competitive steel plants across both the developed and developing world. We are the leader in all the main sectors – automotive, household appliances, packaging and construction. We are also the world’s fourth largest producer of iron ore, with a global portfolio of 16 operating units with mines in operation or development. In 2011, we employed around 261,000 people. Flat Carbon Long Carbon Belgium France Mexico US Algeria Germany Charleroi Basse Indre Lázaro Cárdenas Burns Harbor, IN Annaba Duisburg Ghent Châteauneuf Cleveland, OH -

Case No COMP/M.3334 ΠARCELOR/ THYSSENKRUPP/ STEEL24-7

Case No COMP/M.3334 – ARCELOR/ THYSSENKRUPP/ STEEL24-7 Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EEC) No 4064/89 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 16/02/2004 Also available in the CELEX database Document No 304M3334 Office for Official Publications of the European Communities L-2985 Luxembourg COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 16.02.2004 SG-Greffe(2004) D/200619/200620 In the published version of this decision, PUBLIC VERSION some information has been omitted pursuant to Article 17(2) of Council Regulation (EEC) No 4064/89 concerning non-disclosure of business secrets and MERGER PROCEDURE other confidential information. The omissions are shown thus […]. Where ARTICLE 6(1)(b) DECISION possible the information omitted has been replaced by ranges of figures or a general description. To the notifying parties : Dear Sir/Madam, Subject: Case No COMP/M.3334 Arcelor/Thyssenkrupp/Steel 24-7 Notification of 14 January 2004 pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation No 4064/89 1. On January 14, 2004, the Commission received a notification pursuant to Article 4 of Regulation (EEC) No 4064/891 as last amended by Regulation (EC) No 1310/972 (“the Merger Regulation”) of a proposed concentration by which ThyssenKrupp AG (“ThyssenKrupp”) acquires an additional 25% of the share capital in the existing Joint Venture Steel 24-7. After completion of the transaction, ThyssenKrupp and Arcelor SA (“Arcelor”) will each own 50% of the shares in Steel 24-7. The companies will have joint control over Steel 24-7 within the meaning of Article 3(1) (b) of the Merger Regulation. -

Bibliographie Guy Helminger

225 Bibliographie Guy Helminger Claude D. Conter 1. Auszeichnungen Rost. Kurzgeschichten. Echternach: Éditions Phi 2001 [ins Slowenische übersetzt: Rja. Prevod: Mar- 2000: Autorenstipendium der Filmstiftung NRW tina Soldo; sprema beseda: Vesna Kondrič Horvat. 2001: Autorenstipendium der Filmstiftung NRW Ljubljana: Modrijan 2008]. 2001: Hörspiel des Monats März WDR Ver-Wanderung. Gedichte. Echternach: Éditions Phi 2002: Förderpreis für Jugend-Theater des Landes 2002. Baden-Württemberg Venezuela [englische Übersetzung von: »Morgen ist 2002: Prix Servais (Luxemburg) Regen«]. Translated by Penny Black. London: Oberon 2004: 3sat-Preis (28. Tage der deutschsprachigen Litera- Books 2003 [ins Französische von Anne Montfort tur in Klagenfurt) übersetzt: Venezuale. Montreuil-sous-bois: Editions 2006: Prix du mérite culturel de la ville d’Esch théâtrales 2008]. (Luxemburg) Venezuela. Esch-sur-Alzette: Éditions Phi 2004. 2006: Stadtschreiber in Hyderabad (Indien) Etwas fehlt immer. Erzählungen. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhr- 2012: Poet in Residence an der Universität Duisburg-Essen kamp 2005. Morgen war schon. Roman. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp 2007. 2. Werke Die Ruhe der Schlammkröte. Wiederentdeckt, herausge- 2.1 Bücher geben und mit Anmerkungen von Manuel Andrack, mit Fotos von Ute Behrend. Köln: Kiepenheuer & Die Gegenwartsspringer. Gedichte. Esch-sur-Alzette: Ver- Witsch 2007 (KiWi 978). lag am Schluechthaus 1986. Eine Tasse für Nofretete Nilpferd. Berlin: Bloomsbury Die Ruhe der Schlammkröte. Roman. Köln: [ohne Ver- 2010. lag] 1994. Neubrasilien. Roman: Berlin: Eichborn 2010 [ins Ser- Entfernungen (in Zellophan). Gedichte. Echternach: bokroatische von Meral Tarar-Tutuš übersetzt: Novi Éditions Phi 1998. Brazil. Beograd: Karpos 2011]. Leib eigener Leib. Gedichte. Echternach: Éditions Phi Libellenterz. Gesammelte Gedichte mit CD. Mit einem Gegenüber- 2000. Vorwort von Stefan Weidner. -

Favorite Foods of the World.Xlsx

FAVORITE FOODS OF THE WORLD - VOTING BRACKETS First Round Second Round Third Round Fourth Round Sweet Sixteen Elite Eight Final Four Championship Final Four Elite Eight Sweet Sixteen Fourth Round Third Round Second Round First Round Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Blintzes Duck Confit Papadums Laksa Jambalaya Burrito Cornish Pasty Bulgogi Nori Torta Vegemite Toast Crepes Tagliatelle al Ragù Bouneschlupp Potato Pancakes Hummus Gazpacho Lumpia Philly Cheesesteak Cannelloni Tiramisu Kugel Arepas Cullen Skink Börek Hot and Sour Soup Gelato Bibimbap Black Forest Cake Mousse Croissants Soba Bockwurst Churros Parathas Cream Stew Brie de Meaux Hutspot Crab Rangoon Cupcakes Kartoffelsalat Feta Cheese Kroppkaka PBJ Sandwich Gnocchi Saganaki Mochi Pretzels Chicken Fried Steak Champ Chutney Kofta Pizza Napoletana Étouffée Satay Kebabs Pelmeni Tandoori Chicken Macaroons Yakitori Cheeseburger Penne Pinakbet Dim Sum DIVISION ONE DIVISION TWO Lefse Pad Thai Fastnachts Empanadas Lamb Vindaloo Panzanella Kombu Tourtiere Brownies Falafel Udon Chiles Rellenos Manicotti Borscht Masala Dosa Banh Mi Som Tam BLT Sanwich New England Clam Chowder Smoked Eel Sauerbraten Shumai Moqueca Bubble & Squeak Wontons Cracked Conch Spanakopita Rendang Churrasco Nachos Egg Rolls Knish Pastel de Nata Linzer Torte Chicken Cordon Bleu Chapati Poke Chili con Carne Jollof Rice Ratatouille Hushpuppies Goulash Pernil Weisswurst Gyros Chilli Crab Tonkatsu Speculaas Cookies Fish & Chips Fajitas Gravlax Mozzarella Cheese -

Structural Health Monitoring Using Wireless Technologies: an Ambient Vibration Test on the Adolphe Bridge, Luxembourg City

Originally published as: Oth, A., Picozzi, M. (2012): Structural Health Monitoring Using Wireless Technologies: An Ambient Vibration Test on the Adolphe Bridge, Luxembourg City. ‐ Advances in Civil Engineering DOI: 10.1155/2012/876174 Hindawi Publishing Corporation Advances in Civil Engineering Volume 2012, Article ID 876174, 17 pages doi:10.1155/2012/876174 Research Article Structural Health Monitoring Using Wireless Technologies: An Ambient Vibration Test on the Adolphe Bridge, Luxembourg City Adrien Oth1 and Matteo Picozzi2 1 European Center for Geodynamics and Seismology (ECGS), 19 Rue Josy Welter, 7256 Walferdange, Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, Luxembourg 2 Helmholtz Centre Potsdam-GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Telegrafenberg, 14473 Potsdam, Germany Correspondence should be addressed to Adrien Oth, [email protected] Received 5 September 2011; Accepted 6 December 2011 Academic Editor: Lingyu (Lucy) Yu Copyright © 2012 A. Oth and M. Picozzi. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Major threats to bridges primarily consist of the aging of the structural elements, earthquake-induced shaking and standing waves generated by windstorms. The necessity of information on the state of health of structures in real-time, allowing for timely warnings in the case of damaging events, requires structural health monitoring (SHM) systems that allow the risks of these threats to be mitigated. Here we present the results of a short-duration experiment carried out with low-cost wireless instruments for monitoring the vibration characteristics and dynamic properties of a strategic civil infrastructure, the Adolphe Bridge in Luxembourg City. -

“Social Aspects and Financing of Industrial Restructuring”

INTERNATIONAL LABOUR ORGANIZATION UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE REGIONAL FORUM “Social Aspects and Financing of Industrial Restructuring” 26 and 27 November 2003, Moscow, Russian Federation Topic 2. Social costs of restructuring and their financing: a closer view Restructuring in the Industry of Luxembourg. Major Issues, Actors and Lessons to Learn By Mr. Albert ZENNER – Director Human Resources, Arbed – Arcelor Group Luxembourg (This paper is being circulated by the secretariat as received from the author) UNITED NATIONS Page 1 sur 13 Restructuring in the Industry of Luxembourg Major issues, Actors and Lessons to learn By Albert ZENNER, Director Human Resources, Arbed – Arcelor Group. Luxembourg might be known by many of You as a banking centre or a country hosting European institutions, and some of You will even know that it is the Headquarters of ARCELOR, the world’s largest steel producer, created by the merger of three companies: the French USINOR, the Spanish ACERALIA, and ARBED, the steel company of LUXEMBOURG. All this is true, but LUXEMBOURG is also an independent country, which has undergone deep changes during the last three decades. These changes result from the restructuring of the steel industry, which for more than a century has been the pillar of the Luxembourg economy. During my presentation I will speak about the major issues of this restructuring, the key players, and the lessons to learn from our point of view. I will also try to show how some of the lessons are applied now within the new group ARCELOR. GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION AND POPULATION. For locating Luxembourg geographically we have to zoom the map of Western Europe. -

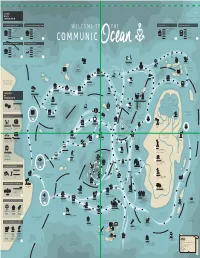

51% 49% 71% 16% 16%

THE WAY WE USE MERKUR - INF OGRAPHIC - C OMMUNICOCEAN - MA Y/JUNE 2015 COMMUNICATION USE OF DAILY NEWSPAPERS (TOP 5) USE OF WEEKLY & BI MONTHLY MAGAZINES (TOP 5) USE OF TV-STATIONS USE OF WEB-SITES (TOP 5) 39,0% LUXEMBURGER WORT 32,8% AUTOTOURING 25,2% RTL TELE LETZEBUERG 25,7% RTL.LU 29,5% L´ESSENTIEL 14,3% AUTO REVUE 3,8% NORDLIICHT TV 16,9% WORT.LU 9,3% TAGEBLATT 13,9% AUTOMOTO 2,1% CHAMBER TV 11,3% L´ESSENTIEL.LU 5,7% LE QUOTIDIEN 11,3% PAPERJAM ... ... 9,2% PUBLIC.LU 2,1% LETZEBUERGER JOURNAL 9,6% CITY MAG ... ... 4,7% TAGEBLATT.LU USE OF MONTHLY MAGAZINES (TOP 5) USE OF RADIO-SATIONS (TOP 5) 23,0% TÉLÉCRAN 36,8% RTL RADIO LETZEBUERG 17,0% LUX-POST WEEK-END 19,6% ELDORADIO 15,7% REVUE 8,5% RTL (GERMAN LANGUAGE) 12,1% CONTACTO 5,4% RADIO LATINA 7,7% LUXBAZAR 4,5% RADIO 100,7 NEW IDEA PRINT MEDIA STORY TELLING 2010s - PRINT NATIVE IN DANGER ADVERTISING MESSENGERS SEA OF PRINT CREATIVITY TRENDY COAST TEXTUAL C ONTENT FRESH IDEAS ISLANDS BUSINESS PLAN FREE NEW SPAPER INFOGRAPHICS 2007 - 1st ISSUE OF L’ESSENTIEL BIG BUDGET FEE / DUTY MAGAZINE MESSENGERS DATA 1932 - 1st MA GAZINE VISUALIZATION CONTINENT AUTOTOURING BY CONSEIL DE AUTOMOBILE CLUB PRESSE M PICTURES A NEWSPAPER I 1848 - 1st ISSUE OF N PRINTING NEWSPAPER RACING PIGE ON LUXEMBURGER WORT S THE HISTORY 1900s - 1st ME CHANIC 1913 - 1st ISSUE 776 B.C. - WINNER LIST COMPUTER PRINTER OF TAGEBLATT LOW BUDGET T OF OF OLYMPIC GAMES SENT R COMMUNICATION BY DOVES E AGE A LANGUAGE B ARRIER REEF NATIO- M NALITY 70,5% LUXEMBOURGISH N E W S P A P E R 55,7% FRENCH GENDER PROF- A REVOLUTION BEGAN 1650 - 1st DAILY 30,6% GERMAN ESSION AS MANKIND STARTED NEWSPAPER 21,0% ENGLISH TO BIND MESSAGES 20,0% PORTUGUESE TO TIME & TO SPACE BIG BUDGET CONSEIL DE HOBBIES PUBLICITÉ INCOME EDU- CLIENTS FUN CATION COAST HOW DID THEY DO THIS ? PRINT R OUTE REPRODUCTION CLIENTS 1450 - GUTENBER G EMOTIONS BUDGET INVENTS PRINT LETTERS COAST CONFUSION TELEVISION TRIANGLE TIME BINDING DEFINITION 1970 - ST ART OF TV-SPOT VISUAL 30.000 B.C.